Sonnenburgplatz

Sonnenburgstraße / Stafflerstraße

Worth knowing

When the Innsbruck municipal council decided in 2016 to "The pasture" to be felled, a storm of indignation broke out. Every trained Innsbruck resident immediately knew which tree it was. The city council for urban planning was inundated with emails in which outraged citizens gave free rein to their emotions over the loss of the tree. All the shouting and screaming did not help. The tree was decrepit and diseased and posed a safety risk due to its imposing size.

The willow in question stood on Sonnenburgplatz, a small inner-city roundabout in Wilten. It covered a stone fountain consisting of two intertwined dolphins spouting water into two shell basins. The square offered neither a cosy bench nor did it commemorate a special event in the city's history. No famous artist had designed it and the once customary title of the fountain Salt and pepper fountain was hardly known to anyone. It was only with the imminent disappearance of the pasture that the people of Innsbruck consciously rediscovered the place, which had long gone unnoticed and overlooked in everyday life.

The fountain was installed on the square in front of the railway station in 1886 to welcome arriving guests to the up-and-coming tourist city of Innsbruck. The two dolphins, symbolising peace and harmony, were the inspiration for the design. When Baron Johann von Sieberer realised his plan in 1905 to celebrate the unification of Innsbruck and Wilten with his much more grandiose Unification fountain the dolphin fountain was moved to Wilten to its current location near the Wilten state railway station, which opened in 1883 and is now the Westbahnhof. The two coats of arms of Innsbruck and Wilten were probably engraved in one of the basins at a later date.

From the 1880s, Sonnenburgplatz developed into Wilten's posh neighbourhood. The name recalls the sovereign jurisdiction of Sonnenburg, which had its origins in the Middle Ages above Mount Isel. Similar to Claudiaplatz in Saggen, residential buildings for the wealthy bourgeoisie were built in the style of the time in Wilten, which was still an independent neighbourhood at the time. A picture postcard from 1910 shows the expanse and splendour of the square, where a cyclist presents her modern sports equipment, without a willow, mind you.

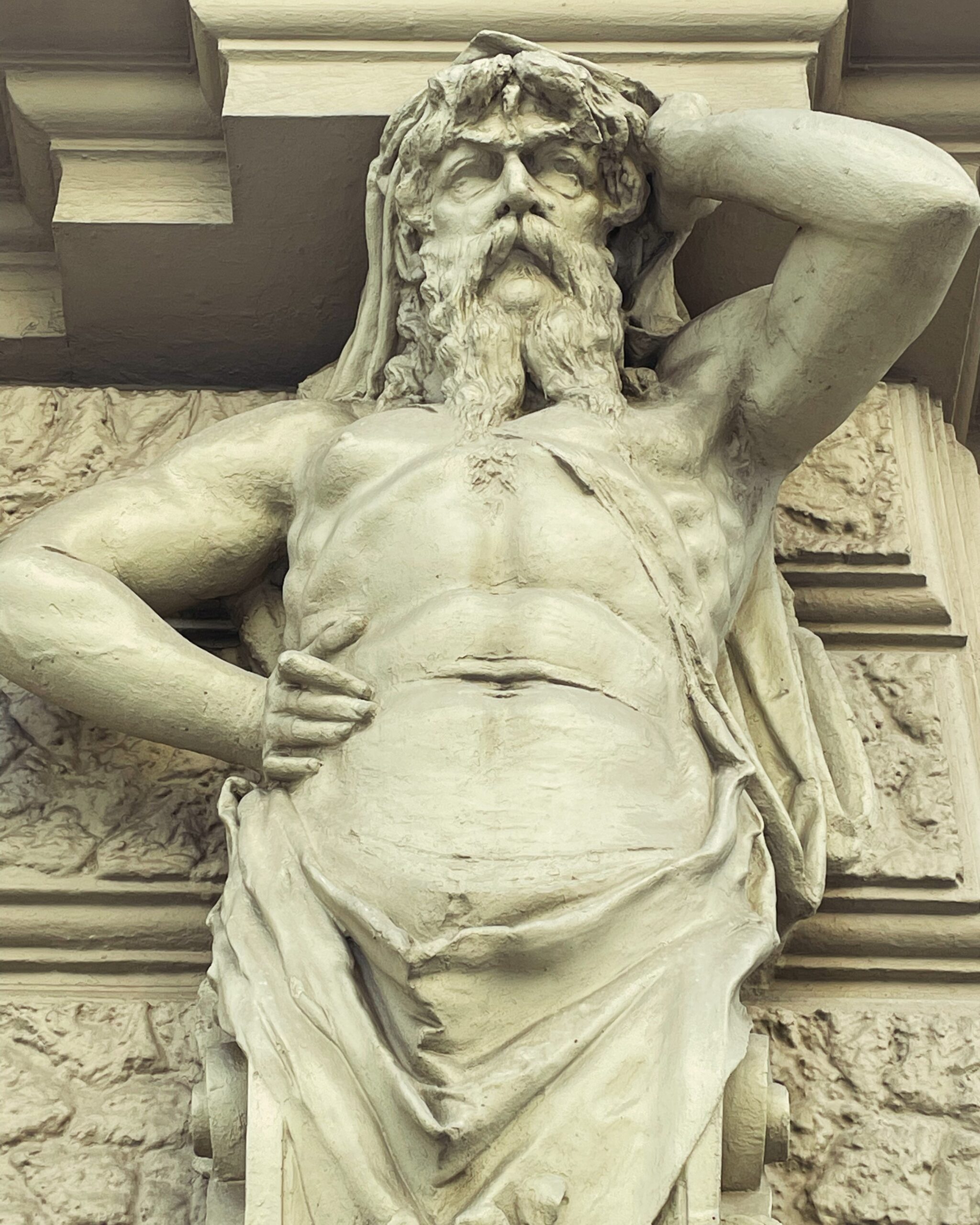

The architectural highlight of the ensemble is the 1902 historicist-style Sonnenburg on the south-west side of the square with its presidential balcony and rich decorations. The Wilhelminian style houses in the side streets are also worth seeing. The statues of bare-breasted ladies and bearded gentlemen at Sonnenburgstraße 17 and the beautiful facades of the colourful buildings in Stafflerstraße to the west of the square allow you to travel back in time. Belle Époque.

By the way: the newly planted tree is growing vigorously and will soon be a worthy, stately successor. What is more exciting is whether it will be possible to upgrade Sonnenburgplatz by freeing it from traffic so that it once again becomes a postcard-worthy motif in Innsbruck's cityscape.

Klingler, Huter, Retter & Co: master builders of expansion

he buildings of the late monarchy still characterise the cityscape of Innsbruck today. The last decades of the 19th century were characterised as Wilhelminian style in the history of Austria. After an economic crisis in 1873, the city began to expand in a revival. From 1880 to 1900, Innsbruck's population grew from 20,000 to 26,000. Wilten, which was incorporated in 1904, tripled in size from 4,000 to 12,000. Between 1850 and 1900, the number of buildings within the city grew from 600 to over 900, most of which were multi-storey apartment blocks, unlike the small buildings of the early modern period. The infrastructure also changed in the course of technical innovations. Gas, water and electricity became part of everyday life for more and more people. The old city hospital gave way to the new hospital. The orphanage and Sieberer's old people's asylum were built in Saggen.

The buildings constructed in the new neighbourhoods were a reflection of this new society. Entrepreneurs, freelancers, employees and workers with political voting rights developed different needs than subjects without this right. From the 1870s, a modern banking system emerged in Innsbruck. Credit institutions such as the Sparkasse, founded in 1821, or the Kreditanstalt, whose building erected in 1910 still stands like a small palace in Maria-Theresien-Straße, not only made it possible to take out loans, but also acted as builders themselves. The apartment blocks that were built also enabled non-homeowners to lead a modern life. Unlike in rural areas of Tyrol, where farming families and their farmhands and maids lived in farmhouses as part of a clan, life in the city came close to the family life we know today. The living space had to correspond to this. The lifestyle of city dwellers demanded multi-room flats and open spaces for relaxation after work. The wealthy middle classes, consisting of entrepreneurs and freelancers, had not yet overtaken the aristocracy, but they had narrowed the gap. They were the ones who not only commissioned private building projects, but also decided on public buildings through their position on the local council.

The 40 years before the First World War were a kind of gold-rush period for construction companies, craftsmen, master builders and architects. The buildings reflected the world view of their clients. Master builders combined several roles and often replaced the architect. Most clients had very clear ideas about what they wanted. They were not to be breathtaking new creations, but copies and references to existing buildings. In keeping with the spirit of the times, the Innsbruck master builders designed the buildings in the styles of historicism and classicism as well as the Tyrolean Heimatstil in accordance with the wishes of the financially strong clients. The choice of style used to build a home was often not only a visual but also an ideological statement by the client. Liberals usually favoured classicism, while conservatives were in favour of the Tyrolean Heimatstil. While the Heimatstil was neo-baroque and featured many paintings, clear forms, statues and columns were style-defining elements in the construction of new classicist buildings. The ideas that people had of classical Greece and ancient Rome were realised in a sometimes wild mix of styles. Not only railway stations and public buildings, but also large apartment blocks and entire streets, even churches and cemeteries were built in this design along the old corridors. The upper middle classes showed their penchant for antiquity with neoclassical façades. Catholic traditionalists had images of saints and depictions of Tyrol's regional history painted on the walls of their Heimatstil houses. While neoclassicism dominates in Saggen and Wilten, most of the buildings in Pradl are in the conservative Heimatstil style.

For a long time, many building experts turned up their noses at the buildings of the upstarts and nouveau riche. Heinrich Hammer wrote in his standard work "Art history of the city of Innsbruck":

"Of course, this first rapid expansion of the city took place in an era that was unfruitful in terms of architectural art, in which architecture, instead of developing an independent, contemporary style, repeated the architectural styles of the past one after the other."

The era of large villas, which imitated the aristocratic residences of days gone by with a bourgeois touch, came to an end after a few wild decades due to a lack of space. Further development of the urban area with individual houses was no longer possible, the space had become too narrow. The area of Falkstrasse / Gänsbachstrasse / Bienerstrasse is still regarded as a neighbourhood today. Villensaggenthe areas to the east as Blocksaggen. In Wilten and Pradl, this type of development did not even occur. Nevertheless, master builders sealed more and more ground in the gold rush. Albert Gruber gave a cautionary speech on this growth in 1907, in which he warned against uncontrolled growth in urban planning and land speculation.

"It is the most difficult and responsible task facing our city fathers. Up until the 1980s (note: 1880), let's say in view of our circumstances, a certain slow pace was maintained in urban expansion. Since the last 10 years, however, it can be said that cityscapes have been expanding at a tremendous pace. Old houses are being torn down and new ones erected in their place. Of course, if this demolition and construction is carried out haphazardly, without any thought, only for the benefit of the individual, then disasters, so-called architectural crimes, usually occur. In order to prevent such haphazard building, which does not benefit the general public, every city must ensure that individuals cannot do as they please: the city must set a limit to unrestricted speculation in the area of urban expansion. This includes above all land speculation."

A handful of master builders and the Innsbruck building authority accompanied this development in Innsbruck. If Wilhelm Greil is described as the mayor of the expansion, the Viennese-born Eduard Klingler (1861 - 1916) probably deserves the title of its architect. Klingler played a key role in shaping Innsbruck's cityscape in his role as a civil servant and master builder. He began working for the state of Tyrol in 1883. In 1889, he joined the municipal building department, which he headed from 1902. In Innsbruck, the commercial academy, the Leitgebule school, the Pradl cemetery, the dermatological clinic in the hospital area, the municipal kindergarten in Michael-Gaismair-Straße, the Trainkaserne (note: today a residential building), the market hall and the Tyrolean State Conservatory are all attributable to Klingler as head of the building department. The Ulrichhaus on Mount Isel, which is now home to the Alt-Kaiserjäger-Club, is a building worth seeing in the Heimatstil style based on his design.

The most important building office in Innsbruck was Johann Huter & Sons. Johann Huter took over his father's brickworks. In 1856, he acquired the first company premises, the Hutergründeon the Innrain. Three years later, the first prestigious headquarters were built in Meranerstraße. The company registration together with his sons Josef and Peter in 1860 marked the official start of the company that still exists today. Huter & Söhne like many of its competitors, saw itself as a complete service provider. The company had its own brickworks, a cement factory, a joinery and a locksmith's shop as well as a planning office and the actual construction company. In 1906/07, the Huters built their own company headquarters at Kaiser-Josef-Straße 15 in the typical style of the last pre-war years. The stately house combines the Tyrolean Heimatstil surrounded by gardens and nature with neo-Gothic and neo-Romanesque elements. Famous from Huter & Söhne buildings erected in Innsbruck include the Monastery of Perpetual Adoration, the parish church of St Nicholas, the first building of the new clinic and several buildings on Claudiaplatz. Shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, the construction company employed more than 700 people.

The second major player was Josef Retter (1872 - 1954). Born in Lower Austria with Tyrolean roots, he completed an apprenticeship as a bricklayer before joining the k.k. State Trade School in Vienna and attended the foreman's school in the building trade department. After gaining professional experience in Vienna, Croatia and Bolzano throughout the Danube Monarchy, he was able to open his own construction company in Innsbruck at the age of 29 thanks to his wife's dowry. Like Huter, his company also included a sawmill, a sand and gravel works and a workshop for stonemasonry work. In 1904, he opened his residential and office building at Schöpfstraße 23a, which is still used today as a Rescuer's house is well known. The dark, neo-Gothic building with its striking bay window with columns and a turret is adorned with a remarkable mosaic depicting an allegory of architecture. The gable relief shows the combination of art and craftsmanship, a symbol of Retter's career. His company was particularly influential in Wilten and Saggen. With the new Academic Grammar School, the castle-like school building for the Commercial Academy, the Evangelical Church of Christ in Saggen, the Zelgerhaus in Anichstraße, the Sonnenburg in Wilten and the neo-Gothic Mentlberg Castle on Sieglanger, he realised many of the most important buildings of this era in Innsbruck.

Late in life but with a similarly practice-orientated background that was typical of 19th century master builders, Anton Fritz started his construction company in 1888. He grew up remotely in Graun in the Vinschgau Valley. After working as a foreman, plasterer and bricklayer, he decided to attend the trade school in Innsbruck at the age of 36. Talent and luck brought him his breakthrough as a planner with the country-style villa at Karmelitergasse 12. In its heyday, his construction company employed 150 people. In 1912, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War and the resulting slump in the construction industry, he handed over his company to his son Adalbert. Anton Fritz's legacy includes his own home at Müllerstraße 4, the Mader house in Glasmalereistraße and houses on Claudiaplatz and Sonnenburgplatz.

With Carl Kohnle, Carl Albert, Karl Lubomirski and Simon Tommasi, Innsbruck had other master builders who immortalised themselves in the cityscape with buildings typical of the late 19th century. They all made Innsbruck's new streets shine in the prevailing architectural zeitgeist of the last 30 years of the Danube Monarchy. Residential buildings, railway stations, official buildings and churches in the vast empire between the Ukraine and Tyrol looked similar across the board. New trends such as Art Nouveau emerged only hesitantly. In Innsbruck, it was the Munich architect Josef Bachmann who set a new accent in civic design with the redesign of the façade of the Winklerhaus. Building activity came to a halt at the beginning of the First World War. After the war, the era of neoclassical historicism and Heimatstil was finally history. Times were more austere and the requirements for residential buildings had changed. More important than a representative façade and large, stately rooms became affordable living space and modern facilities with sanitary installations during the housing shortage of the sparse, young Republic of German-Austria. The more professional training of master builders and architects at the k.k. Staatsgewerbeschule also contributed to a new understanding of the building trade than the often self-taught veterans of the gold-digger era of classicism had. Walks in Saggen and parts of Wilten and Pradl still take you back to the days of the Wilhelminian style. Claudiaplatz and Sonnenburgplatz are among the most impressive examples. The construction company Huter and Sons still exists today. The company is now located in Sieglanger in Josef-Franz-Huter-Straße, named after the company founder. Although the residential building in Kaiser-Josef-Straße no longer bears the company's logo, its opulence is still a relic of the era that changed Innsbruck's appearance forever. In addition to his home in Schöpfstraße, Wilten is home to a second building belonging to the Retter family. On the Innrain opposite the university is the Villa Retter. Josef Retter's eldest daughter Maria Josefa, who herself was educated by the reform pedagogue Maria Montessori, opened the first „House of the child“ of Innsbruck. Above the entrance is a portrait of the patron Josef Retter, while the south façade is adorned with a mosaic in the typical style of the 1930s, hinting at the building's original purpose. A smiling, blonde girl embraces her mother, who is holding a book, and her father, who is carrying a hammer. The small burial chapel at the Westfriedhof cemetery, which serves as the Retters' family burial place, is also a legacy of this important family for Innsbruck that is well worth seeing.

The year 1848 and its consequences

The year 1848 occupies a mythical place in European history. Although the hotspots were not to be found in secluded Tyrol, but in the major metropolises such as Paris, Vienna, Budapest, Milan and Berlin, even in the Holy Land however, the revolutionary year left its mark. In contrast to the rural surroundings, an enlightened educated middle class had developed in Innsbruck. Enlightened people no longer wanted to be subjects of a monarch or sovereign, but citizens with rights and duties towards the state. Students and freelancers demanded political participation, freedom of the press and civil rights. Workers demanded better wages and working conditions. Radical liberals and nationalists in particular even questioned the omnipotence of the church.

In March 1848, this socially and politically highly explosive mixture erupted in riots in many European cities. In Innsbruck, students and professors celebrated the newly enacted freedom of the press with a torchlight procession. On the whole, however, the revolution proceeded calmly in the leisurely Tyrol. It would be foolhardy to speak of a spontaneous outburst of emotion; the date of the procession was postponed from 20 to 21 March due to bad weather. There were hardly any anti-Habsburg riots or attacks; a stray stone thrown into a Jesuit window was one of the highlights of the Alpine version of the 1848 revolution. The students even helped the city magistrate to monitor public order in order to show their gratitude to the monarch for the newly granted freedoms and their loyalty.

The initial enthusiasm for bourgeois revolution was quickly replaced by German nationalist, patriotic fervour in Innsbruck. On 6 April 1848, the German flag was waved by the governor of Tyrol during a ceremonial procession. A German flag was also raised on the city tower. Tricolour was hoisted. While students, workers, liberal-nationalist-minded citizens, republicans, supporters of a constitutional monarchy and Catholic conservatives disagreed on social issues such as freedom of the press, they shared a dislike of the Italian independence movement that had spread from Piedmont and Milan to northern Italy. Innsbruck students and marksmen marched to Trentino with the support of the k.k. The Innsbruck students and riflemen moved into Trentino to nip the unrest and uprisings in the bud. Well-known members of this corps were Father Haspinger, who had already fought with Andreas Hofer in 1809, and Adolf Pichler. Johann Nepomuk Mahl-Schedl, wealthy owner of Büchsenhausen Castle, even equipped his own company with which he marched across the Brenner Pass to secure the border.

The city of Innsbruck, as the political and economic centre of the multinational crown land of Tyrol and home to many Italian speakers, also became the arena of this nationality conflict. Combined with copious amounts of alcohol, anti-Italian sentiment in Innsbruck posed more of a threat to public order than civil liberties. A quarrel between a German-speaking craftsman and an Italian-speaking Ladin got so heated that it almost led to a pogrom against the numerous businesses and restaurants owned by Italian-speaking Tyroleans.

The relative tranquillity of Innsbruck suited the imperial house, which was under pressure. When things did not stop boiling in Vienna even after March, Emperor Ferdinand fled to Tyrol in May. According to press reports from this time, he was received enthusiastically by the population.

"Wie heißt das Land, dem solche Ehre zu Theil wird, wer ist das Volk, das ein solches Vertrauen genießt in dieser verhängnißvollen Zeit? Stützt sich die Ruhe und Sicherheit hier bloß auf die Sage aus alter Zeit, oder liegt auch in der Gegenwart ein Grund, auf dem man bauen kann, den der Wind nicht weg bläst, und der Sturm nicht erschüttert? Dieses Alipenland heißt Tirol, gefällts dir wohl? Ja, das tirolische Volk allein bewährt in der Mitte des aufgewühlten Europa die Ehrfurcht und Treue, den Muth und die Kraft für sein angestammtes Regentenhaus, während ringsum Auflehnung, Widerspruch. Trotz und Forderung, häufig sogar Aufruhr und Umsturz toben; Tirol allein hält fest ohne Wanken an Sitte und Gehorsam, auf Religion, Wahrheit und Recht, während anderwärts die Frechheit und Lüge, der Wahnsinn und die Leidenschaften herrschen anstatt folgen wollen. Und während im großen Kaiserreiche sich die Bande überall lockern, oder gar zu lösen drohen; wo die Willkühr, von den Begierden getrieben, Gesetze umstürzt, offenen Aufruhr predigt, täglich mit neuen Forderungen losgeht; eigenmächtig ephemere- wie das Wetter wechselnde Einrichtungen schafft; während Wien, die alte sonst so friedliche Kaiserstadt, sich von der erhitzten Phantasie der Jugend lenken und gängeln läßt, und die Räthe des Reichs auf eine schmähliche Weise behandelt, nach Laune beliebig, und mit jakobinischer Anmaßung, über alle Provinzen verfügend, absetzt und anstellt, ja sogar ohne Ehrfurcht, den Kaiaer mit Sturm-Petitionen verfolgt; während jetzt von allen Seiten her Deputationen mit Ergebenheits-Addressen mit Bittgesuchen und Loyalitätsversicherungen dem Kaiser nach Innsbruck folgen, steht Tirol ganz ruhig, gleich einer stillen Insel, mitten im brausenden Meeressturme, und des kleinen Völkchens treue Brust bildet, wie seine Berge und Felsen, eine feste Mauer in Gesetz und Ordnung, für den Kaiser und das Vaterland."

In June, a young Franz Josef, not yet emperor at the time, also stayed at the Hofburg on his way back from the battlefields of northern Italy instead of travelling directly to Vienna. Innsbruck was once again the royal seat, if only for one summer. While blood was flowing in Vienna, Milan and Budapest, the imperial family enjoyed life in the Tyrolean countryside. Ferdinand, Franz Karl, his wife Sophie and Franz Josef received guests from foreign royal courts and were chauffeured in four-in-hand carriages to the region's excursion destinations such as Weiherburg Castle, Stefansbrücke Bridge, Kranebitten and high up to Heiligwasser. A little later, however, the cosy atmosphere came to an end. Under gentle pressure, Ferdinand, who was no longer considered fit for office, passed the torch of regency to Franz Josef I. In July 1848, the first parliamentary session was held in the Court Riding School in Vienna. The first constitution was enacted. However, the monarchy's desire for reform quickly waned. The new parliament was an imperial council, it could not pass any binding laws, the emperor never attended it during his lifetime and did not understand why the Danube Monarchy, as a divinely appointed monarchy, needed this council.

Nevertheless, the liberalisation that had been gently set in motion took its course in the cities. Innsbruck was given the status of a town with its own statute. Innsbruck's municipal law provided for a right of citizenship that was linked to ownership or the payment of taxes, but legally guaranteed certain rights to members of the community. Birthright citizenship could be acquired by birth, marriage or extraordinary conferment and at least gave male adults the right to vote at municipal level. If you got into financial difficulties, you had the right to basic support from the town.

Thanks to the census-based majority voting system, the Greater German liberal faction prevailed within the city government, in which merchants, tradesmen, industrialists and innkeepers set the tone. On 2 June 1848, the first edition of the liberal and Greater German-minded Innsbrucker Zeitungfrom which the above article on the emperor's arrival in Innsbruck is taken. Conservatives, on the other hand, read the Volksblatt for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. Moderate readers who favoured a constitutional monarchy preferred to consume the Bothen for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. However, the freedom of the press soon came to an end. The previously abolished censorship was reintroduced in parts. Newspaper publishers had to undergo some harassment by the authorities. Newspapers were not allowed to write against the state government, monarchy or church.

"Anyone who, by means of printed matter, incites, instigates or attempts to incite others to take action which would bring about the violent separation of a part from the unified state... of the Austrian Empire... or the general Austrian Imperial Diet or the provincial assemblies of the individual crown lands.... Imperial Diet or the Diet of the individual Crown Lands... violently disrupts... shall be punished with severe imprisonment of two to ten years."

After Innsbruck officially replaced Meran as the provincial capital in 1849 and thus finally became the political centre of Tyrol, political parties were formed. From 1868, the liberal and Greater German orientated party provided the mayor of the city of Innsbruck. The influence of the church declined in Innsbruck in contrast to the surrounding communities. Individualism, capitalism, nationalism and consumerism stepped into the breach. New worlds of work, department stores, theatres, cafés and dance halls did not supplant religion in the city either, but the emphasis changed as a result of the civil liberties won in 1848.

Perhaps the most important change to the law was the Basic relief patent. In Innsbruck, the clergy, above all Wilten Abbey, held a large proportion of the peasant land. The church and nobility were not subject to taxation. In 1848/49, manorial rule and servitude were abolished in Austria. Land rents, tithes and roboters were thus abolished. The landlords received one third of the value of their land from the state as part of the land relief, one third was regarded as tax relief and the farmers had to pay one third of the relief themselves. They could pay off this amount in instalments over a period of twenty years.

The after-effects can still be felt today. The descendants of the then successful farmers enjoy the fruits of prosperity through inherited land ownership, which can be traced back to the land relief of 1848, as well as political influence through land sales for housing construction, leases and public sector redemptions for infrastructure projects. The land-owning nobles of the past had to resign themselves to the ignominy of pursuing middle-class labour. The transition from birthright to privileged status within society was often successful thanks to financial means, networks and education. Many of Innsbruck's academic dynasties began in the decades after 1848.

Das bis dato unbekannte Phänomen der Freizeit kam, wenn auch für den größten Teil nur spärlich, auf und begünstigte gemeinsam mit frei verfügbarem Einkommen einer größeren Anzahl an Menschen Hobbies. Zivile Organisationen und Vereine, vom Lesezirkel über Sängerbünde, Feuerwehren und Sportvereine, gründeten sich. Auch im Stadtbild manifestierte sich das Revolutionsjahr. Parks wie der Englische Garten beim Schloss Ambras oder der Hofgarten waren nicht mehr exklusiv der Aristokratie vorbehalten, sondern dienten den Bürgern als Naherholungsgebiete vom beengten Dasein. In St. Nikolaus entstand der Waltherpark als kleine Ruheoase. Einen Stock höher eröffnete im Schloss Büchsenhausen Tirols erste Schwimm- und Badeanstalt, wenig später folgte ein weiteres Bad in Dreiheiligen. Ausflugsgasthöfe rund um Innsbruck florierten. Neben den gehobenen Restaurants und Hotels entstand eine Szene aus Gastwirtschaften, in denen sich auch Arbeiter und Angestellte gemütliche Abende bei Theater, Musik und Tanz leisten konnten.

Wilhelm Greil: DER Bürgermeister Innsbrucks

One of the most important figures in the town's history was Wilhelm Greil (1850 - 1923). From 1896 to 1923, the entrepreneur held the office of mayor, having previously helped to shape the city's fortunes as deputy mayor. It was a time of growth, the incorporation of entire neighbourhoods, technical innovations and new media. The four decades between the economic crisis of 1873 and the First World War were characterised by unprecedented economic growth and rapid modernisation. Private investment in infrastructure such as railways, energy and electricity was desired by the state and favoured by tax breaks in order to lead the countries and cities of the ailing Danube monarchy into the modern age. The city's economy boomed. Businesses sprang up in the new districts of Pradl and Wilten, attracting workers. Tourism also brought fresh capital into the city. At the same time, however, the concentration of people in a confined space under sometimes precarious hygiene conditions also brought problems. The outskirts of the city and the neighbouring villages in particular were regularly plagued by typhus.

Innsbruck city politics, in which Greil was active, was characterised by the struggle between liberal and conservative forces. Greil belonged to the "Deutschen Volkspartei", a liberal and national-Great German party. What appears to be a contradiction today, liberal and national, was a politically common and well-functioning pair of ideas in the 19th century. The Pan-Germanism was not a political peculiarity of a radical right-wing minority, but rather a centrist trend, particularly in German-speaking cities in the Reich, which was significant in various forms across almost all parties until after the Second World War. Innsbruckers who were self-respecting did not describe themselves as Austrians, but as Germans. Those who were members of the liberal Innsbrucker Nachrichten of the period around the turn of the century, you will find countless articles in which the common ground between the German Empire and the German-speaking countries was made the topic of the day, while distancing themselves from other ethnic groups within the multinational Habsburg Empire. Greil was a skilful politician who operated within the predetermined power structures of his time. He knew how to skilfully manoeuvre around the traditional powers, the monarchy and the clergy and to come to terms with them.

Taxes, social policy, education, housing and the design of public spaces were discussed with passion and fervour. Due to an electoral system based on voting rights via property classes, only around 10% of the entire population of Innsbruck were able to go to the ballot box. Women were excluded as a matter of principle. Relative suffrage applied within the three electoral bodies, which meant as much as: The winner takes it all. Greil wohne passenderweise ähnlich wie ein Renaissancefürst. Er entstammte der großbürgerlichen Upper Class. Sein Vater konnte es sich leisten, im Palais Lodron in der Maria-Theresienstraße die Homebase der Familie zu gründen. Massenparteien wie die Sozialdemokratie konnten sich bis zur Wahlrechtsreform der Ersten Republik nicht durchsetzen. Konservative hatten es in Innsbruck auf Grund der Bevölkerungszusammensetzung, besonders bis zur Eingemeindung von Wilten und Pradl, ebenfalls schwer. Bürgermeister Greil konnte auf 100% Rückhalt im Gemeinderat bauen, was die Entscheidungsfindung und Lenkung natürlich erheblich vereinfachte. Bei aller Effizienz, die Innsbrucker Bürgermeister bei oberflächlicher Betrachtung an den Tag legten, sollte man nicht vergessen, dass das nur möglich war, weil sie als Teil einer Elite aus Unternehmern, Handelstreibenden und Freiberuflern ohne nennenswerte Opposition und Rücksichtnahme auf andere Bevölkerungsgruppen wie Arbeitern, Handwerkern und Angestellten in einer Art gewählten Diktatur durchregierten. Das Reichsgemeindegesetz von 1862 verlieh Städten wie Innsbruck und damit den Bürgermeistern größere Befugnisse. Es verwundert kaum, dass die Amtskette, die Greil zu seinem 60. Geburtstag von seinen Kollegen im Gemeinderat verliehen bekam, den Ordensketten des alten Adels erstaunlich ähnelte.

Under Greil's aegis and the general economic upturn, fuelled by private investment, Innsbruck expanded at a rapid pace. In true merchant style, the municipal council purchased land with foresight in order to enable the city to innovate. The politician Greil was able to rely on the civil servants and town planners Eduard Klingler, Jakob Albert and Theodor Prachensky for the major building projects of the time. Infrastructure projects such as the new town hall in Maria-Theresienstraße in 1897, the opening of the Mittelgebirgsbahn railway, the Hungerburgbahn and the Karwendelbahn wurden während seiner Regierungszeit umgesetzt. Weitere gut sichtbare Meilensteine waren die Erneuerung des Marktplatzes und der Bau der Markthalle. Neben den prestigeträchtigen Großprojekten entstanden in den letzten Jahrzehnten des 19. Jahrhunderts aber viele unauffällige Revolutionen. Vieles, was in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts vorangetrieben wurde, gehört heute zum Alltag. Für die Menschen dieser Zeit waren diese Dinge aber eine echte Sensation und lebensverändernd. Bereits Greils Vorgänger Bürgermeister Heinrich Falk (1840 – 1917) hatte erheblich zur Modernisierung der Stadt und zur Besiedelung des Saggen beigetragen. Seit 1859 war die Beleuchtung der Stadt mit Gasrohrleitungen stetig vorangeschritten. Mit dem Wachstum der Stadt und der Modernisierung wurden die Senkgruben, die in Hinterhöfen der Häuser als Abort dienten und nach Entleerung an umliegende Landwirte als Dünger verkauft wurden, zu einer Unzumutbarkeit für immer mehr Menschen. 1880 wurde das RaggingThe city was responsible for the emptying of the lavatories. Two pneumatic machines were to make the process at least a little more hygienic. Between 1887 and 1891, Innsbruck was equipped with a modern high-pressure water pipeline, which could also be used to supply fresh water to flats on higher floors. For those who could afford it, this was the first opportunity to install a flush toilet in their own home.

Greil continued this campaign of modernisation. After decades of discussions, the construction of a modern alluvial sewerage system began in 1903. Starting in the city centre, more and more districts were connected to this now commonplace luxury. By 1908, only the Koatlackler Mariahilf und St. Nikolaus nicht an das Kanalsystem angeschlossen. Auch der neue Schlachthof im Saggen erhöhte Hygiene und Sauberkeit in der Stadt. Schlecht kontrollierte Hofschlachtungen gehörten mit wenigen Ausnahmen der Vergangenheit an. Das Vieh kam im Zug am Sillspitz an und wurde in der modernen Anlage fachgerecht geschlachtet. Greil überführte auch das Gaswerk in Pradl und das Elektrizitätswerk in Mühlau in städtischen Besitz. Die Straßenbeleuchtung wurde im 20. Jahrhundert von den Gaslaternen auf elektrisches Licht umgestellt. 1888 übersiedelte das Krankenhaus von der Maria-Theresienstraße an seinen heutigen Standort. Bürgermeister und Gemeinderat konnten sich bei dieser Innsbrucker Renaissance neben der wachsenden Wirtschaftskraft in der Vorkriegszeit auch auf Mäzen aus dem Bürgertum stützen. Waren technische Neuerungen und Infrastruktur Sache der Liberalen, verblieb die Fürsorge der Ärmsten weiterhin bei klerikal gesinnten Kräften, wenn auch nicht mehr bei der Kirche selbst. Freiherr Johann von Sieberer stiftete das Greisenasyl und das Waisenhaus im Saggen. Leonhard Lang stiftete das Gebäude in der Maria-Theresienstraße, in der sich bis heute das Rathaus befindet gegen das Versprechen der Stadt ein Lehrlingsheim zu bauen.

Im Gegensatz zur boomenden Vorkriegsära war die Zeit nach 1914 vom Krisenmanagement geprägt. In seinen letzten Amtsjahren begleitete Greil Innsbruck am Übergang von der Habsburgermonarchie zur Republik durch Jahre, die vor allem durch Hunger, Elend, Mittelknappheit und Unsicherheit geprägt waren. Er war 68 Jahre alt, als italienische Truppen nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg die Stadt besetzten und Tirol am Brenner geteilt wurde. Das Ende der Monarchie und des Zensuswahlrechts bedeuteten auch den Niedergang der Liberalen in Innsbruck, auch wenn Greil das in seiner aktiven Karriere nur teilweise miterlebte. 1919 konnten die Sozialdemokraten in Innsbruck zwar zum ersten Mal den Wahlsieg davontragen, dank der Mehrheiten im Gemeinderat blieb Greil aber Bürgermeister. 1928 verstarb er als Ehrenbürger der Stadt Innsbruck im Alter von 78 Jahren. Die Wilhelm-Greil-Straße war noch zu seinen Lebzeiten nach ihm benannt worden.

Medieval and early modern town law

Innsbruck, heute selbsternannte Weltstadt, hatte sich von einem römischen Castell über ein Kloster, zu dem mehrere Weiler gehörten zu einer Marktsiedlung und erst nach Hunderten von Jahren zu einer rechtlich anerkannten Stadt entwickelt. Mit dieser rechtlichen Anerkennung gingen Rechte und Pflichten einher. Verbunden mit dem vom Landesfürsten verliehenen Stadtrecht war das Marktrecht, das Zollrecht und eine eigene Gerichtsbarkeit. Bürger mussten im Gegenzug den Bürgereid leisten, der zu Steuern und Wehrdienst verpflichtete und die Stadt mit Mauer und Wehranlage sichern. Ab 1511 war der Stadtrat auch verpflichtet, laut dem Landlibell Kaiser Maximilians ein Kontingent an Wehrpflichtigen im Falle der Landesverteidigung zu stellen. Darüber hinaus gab es Freiwillige, die sich im Freifähnlein der Stadt zum Kriegsdienst melden konnten, so waren zum Beispiel bei der Türkenbelagerung Wiens 1529 auch Innsbrucker unter den Stadtverteidigern. Der Sold war vor allem für die ärmeren Bürger reizvoll. Die Stadtbürger unterlagen damit nicht mehr direkt dem Landesfürsten, sondern der städtischen Gerichtsbarkeit, zumindest innerhalb der Stadtmauern. Das geflügelte Wort "Stadtluft macht frei" rührt daher, dass man nach einem Jahr in der Stadt von allen Verbindlichkeiten seines ehemaligen Herrn frei war. Faktisch war es der Übergang von einem Rechtsystem in ein anderes. Um 1500 änderte sich die Situation im Zuzug. Der Platz war eng geworden im neuen, rasch wachsenden Innsbruck unter Maximilian I. Es war nur noch freien Untertanen aus ehelicher Geburt möglich, das Stadtrecht zu erlangen. Nicht mehr jeder durfte in die Stadt ziehen. Kaufleute und Finanziers verzichteten auf dieses Recht meist, war es doch mit allerhand Pflichten verbunden, die bei den mobilen Schichten dieser Zeit die Anreize weit überstiegen. Um Stadtbürger zu werden, mussten entweder Hausbesitz oder Fähigkeiten in einem Handwerk nachgewiesen werden, an der die Zünfte der Stadt interessiert waren. Diese Handwerkszünfte übten teilweise eine eigene Gerichtsbarkeit neben der städtischen Gerichtsbarkeit unter ihren Mitgliedern aus. Löhne, Preise und das soziale Leben wurden von den Zünften unter Aufsicht des Landesfürsten geregelt. Man könnte von einer frühen Sozialpartnerschaft sprechen, sorgten die Zünfte doch auch für die soziale Sicherheit ihrer Mitglieder bei Krankheit oder Berufsunfähigkeit. Die einzelnen Gewerbe wie Schlosser, Gerber, Plattner, Tischler, Bäcker, Metzger oder Schmiede hatten jeweils ihre Zunft, der ein Meister vorstand. Es waren soziale Strukturen innerhalb der Stadtstruktur, die großen Einfluss auf die Politik hatten, konnten sie das Wahlverhalten ihrer Mitglieder stark mitbestimmen. Handwerker zählten, anders als Bauen, zu den mobilen Schichten im Mittelalter und der frühen Neuzeit. Sie gingen nach der Lehrzeit auf die Walz, bevor sie sich der Meisterprüfung unterzogen und entweder nach Hause zurückkehrten oder sich in einer anderen Stadt niederließen. Über Handwerker erfolgte nicht nur Wissenstransfer, auch kulturelle, soziale und politische Ideen verbreiteten sich in Europa durch sie. Ab dem 14. Jahrhundert besaß Innsbruck nachweisbar einen Stadtrat und einen Bürgermeister, der von der Bürgerschaft jährlich gewählt wurde. Es waren anderes als heute keine geheimen, sondern öffentliche Wahlen, die alljährlich rund um die Weihnachtszeit abgehalten wurden. Da nicht jeder Einwohner Bürger war, kann man auch nicht von einer Demokratie sprechen, eher war es eine Wahl der Oberschicht, die ihre Vertreter wählte. Im Innsbrucker Geschichtsalmanach von 1948 findet man Aufzeichnungen über die Wahl des Jahres 1598.

The Feast of St. Erhard, i.e., January 8th, played a significant role in the lives of the citizens of Innsbruck each year. On this day, they gathered to elect the city officials, namely the mayor, city judge, public orator, and the twelve-member council. A detailed account of the election process between 1598 and 1607 is provided by a protocol preserved in the city archive: "... The ringing of the great bell summoned the council and the citizenry to the town hall, and once the honorable council and the entire community were assembled at the town hall, the honorable council first convened in the council chamber and heard the farewell of the outgoing mayor of the previous year, Augustin Tauscher."

Der Bürgermeister vertrat die Stadt gegenüber den anderen Ständen und dem Landesfürsten, der die Oberherrschaft über die Stadt je nach Epoche mal mehr, mal weniger intensiv ausübte. Jeder Stadtrat hatte eigene, klar zugeteilte Aufgaben zu erfüllen wie die Überwachung des Marktrechts, die Betreuung des Spitals und der Armenfürsorge oder die für Innsbruck besonders wichtige Zollordnung. Bei all diesen politischen Vorgängen sollte man sich stets in Erinnerung rufen, dass Innsbruck im 16. Jahrhundert etwa 5000 Einwohner hatte, von denen nur ein kleiner Teil das Bürgerrecht besaß. Besitzlose, fahrendes Volk, Erwerbslose, Dienstboten, Diplomaten, Angestellte, ab dem 17. Jahrhundert Studenten, leider auch Frauen waren keine wahlberechtigten Bürger. Die Wahlen basierten also auf persönlichen Verbindlichkeiten und Bekanntschaften in dieser kleinen Gemeinde. Ebenfalls ab dem 14. Jahrhundert mussten die Steuern, die von den Bürgern gezahlt wurden, nicht mehr an den Landesfürsten weitergegeben werden. Es gab eine fixe Abgabe von der Stadt an den Landesfürsten. Welche Gruppe innerhalb der Stadt welche Steuer zu bezahlen hatte, konnte die Stadtregierung selbst festlegen. Die Differenz zwischen den Einnahmen und den Ausgaben durfte die Stadt nach ihrem Gutdünken verwalten. Zu den Ausgaben neben der Verteidigung gehörte die Armenfürsorge. Notleidende Bürger konnten in der „Siedelküche" meals, if they had the civil rights. Building rights were also the responsibility of the city administration. As in most medieval towns, the wooden buildings within the town walls fell victim to flames more often than the inhabitants would have liked. Another point that was regulated in the town charter was the right to organise markets. The town had control over the goods on offer and their quantity and quality. Bread, for example, was sold by the "Bred guardian" were weighed in the bread bank in the town hall to prevent usury, which was a punishable offence. Interestingly, the town council could also appoint the pastor. Pastoral care was a real need, so the quality of the sermon or choir singing was very important. Compliance with religious order was also monitored by the city. Heretics and theologically rebellious people were not reprimanded by the church, but by the city government and, in some cases, even sent to prison.

In addition to the taxes that citizens had to pay, customs duties were an important source of income for Innsbruck. Customs duties were levied at the city gate at the Inn bridge. There were two types of customs duty. The small duty was based on the number of draught animals in the wagon, the large duty on the type and quantity of goods. The customs revenue was shared between Innsbruck and Hall. Hall had the task of maintaining the Inn bridge. With the increasing centralisation under Maria Theresa and Joseph II, taxes and customs duties were gradually centralised and collected by the Imperial Court Chamber. As a result, Innsbruck, like many municipalities at the time, lost a large amount of revenue, which was only partially compensated for by equalisation.

Contrary to popular belief, the Middle Ages were not a lawless time of arbitrariness. In Innsbruck, as well as in the province of Tyrol, there was a code that regulated right and wrong as well as the rights and duties of citizens very precisely. These regulations changed according to the customs of the time. The penal system also included less humane methods than are common today, but torture was not used indiscriminately and arbitrarily. However, torture was also regulated as part of the procedure in particularly serious cases. Until the 17th century, suspects and criminals in Innsbruck were held and tortured in the herb tower at the south-east corner of the city wall, on today's Herzog-Otto-Ufer. The medieval court days were held at the "Dingstätte" is held outdoors. The tradition of the Thing goes back to the old Germanic Thingwhere all free men gathered to dispense justice. The city council appointed a judge who was responsible for all offences that were not subject to the blood court. Punishments ranged from fines to pillorying and imprisonment. There was no police force, but the town magistrate employed servants and town watchmen were posted at the town gates to keep the peace. It was a civic duty to help catch criminals. Vigilante justice was forbidden. Serious crimes such as theft, murder and arson were subject to the blood law. The provincial court still had jurisdiction over these offences. In the case of Innsbruck, the provincial court was on the Sonnenburgwhich was located south above Innsbruck. From 1817 - 1887 the Leuthaus the seat of the court judge at Wilten Abbey (67). Over the years, the places of execution were located in several places, usually outside the town walls. For a long time, a gallows was set up on a hill in today's Dreiheiligen district next to the main road that ran past here. The corpses were often left hanging for a long time as a deterrent. The Köpflplatz befand sich an der heutigen Weiherburggasse in AnpruggenIt was not uncommon for the condemned man to give his executioner a kind of tip so that he would endeavour to aim as accurately as possible in order to make the execution as painless as possible. Sensational delinquents such as the "heretic" Jakob Hutter (87) or the captured leaders of the peasant uprisings of 1525 and 1526 were executed before the Goldenen Dachl executed in a manner suitable for the public. "Embarrassing" punishments such as quartering or wheeling, from the Latin word poena were not the order of the day, but could be ordered in special cases. From the late 15th century, Innsbruck's executioner was centralised and responsible for several courts and was based in Hall. Executions were a public demonstration of the authorities' power. It was seen as a way of cleansing society of criminals. The executed were buried outside the consecrated area of the cemeteries.

With the centralisation of law under Maria Theresa and Joseph II in the 18th century and the General Civil Code in the 19th century under Franz I, the law passed from cities and sovereigns to the monarch and their administrative bodies at various levels. Under Joseph II, the death penalty was even suspended for a short time. Torture had already been abolished before then. The Enlightenment had fundamentally changed the concept of justice, punishment and rehabilitation. While it had previously been a criminal offence and sometimes punished with the pillory or worse if a woman gave birth to an illegitimate child, this was no longer a criminal offence. The children were handed over to Catholic foster parents or an orphanage. The Christian morals of the people did not follow suit with the law. Women remained marginalised until well into the 20th century, even though a significant proportion of children were illegitimate. Goethe's Faust recounts the fate of one such woman who killed herself out of shame. The collection of taxes was also centralised, which resulted in a great loss of importance for the local nobility and an increase in the status of civil servants. The new legal concepts also gradually changed the urban landscape. The herb tower as a dungeon became obsolete; instead, a penitentiary was needed, today's Turnus clubhousein St Nicholas.

The development of the legal system to the one we have today in the Republic of Austria and its cities was a long process. While the mayor and the city council are still elected, the judge is appointed at the district court. The employees of the city magistrate are hardly civil servants any more and the young citizens' party, to which the city invites its youngest members on their coming of age, is not very festive or even significant. There are also no more guilds. However, the dispute over who is a "real" Innsbrucker and who is not is a continuity that has persisted to this day. Unfortunately, it is often forgotten that migration and exchange with others have always guaranteed prosperity and made Innsbruck the liveable city it is today.