Philippine-Welser-Straße

Philippine-Welser-Straße

Worth knowing

If you turn into Philippine-Welser-Straße from the west, the large blocks of flats make it hard to believe that this was the original village of Amras. To this day, real Amras locals mockingly call the residents of the modern complexes "Zuagroaste“, „Blöckler" or "Stiegenhäusler". After a few metres, however, you can already see the farmhouses that characterise Amras as a rural village in the city.

The street is named after Philippine Welser, the wife of Ferdinand II, who is still popular with the population today. The princess would have been delighted with the lush gardens in front of the Amras farmhouses, some of which look like small castles. The façades and bay windows are decorated with Catholic motifs in the style of rural Baroque, which are embedded in rural Tyrolean life. The lavishly renovated farmhouses give an idea of how the modern farmers of Amras earned their living less from time-consuming field labour and more from the sale and management of real estate, which was granted to them by the 1848 land relief and has increased in value over the centuries. House numbers 85, 88 and 101 are particularly worth seeing.

Remarkable is the recurring depiction of the "Amraser Gnadenmutter", a local variation on the veneration of the Madonna. According to legend, the Mother of mercy a child who had fallen out of a window. The princely parents then donated an image of the Mother of mercywhich has a special place in the folklore of the region and is a popular motif for Amras farmhouses. It is an example of legendary figures that combine with Christianity to form a particularly pious mixture.

The painting on the façade above the entrance to the Amras parish church by Tyrolean artist Hans Andre shows the Mother of mercy next to a Tyrolean marksman and a woman in traditional Tyrolean costume. The Amras parish church can be seen in the background. The depiction of the church on itself is a special expression of Tyrolean popular piety that can be seen on several places of worship in the region. It is a symbol of the Holy Land Tyrolwhich is based on the covenant with the Sacred Heart of Jesus of 1796.

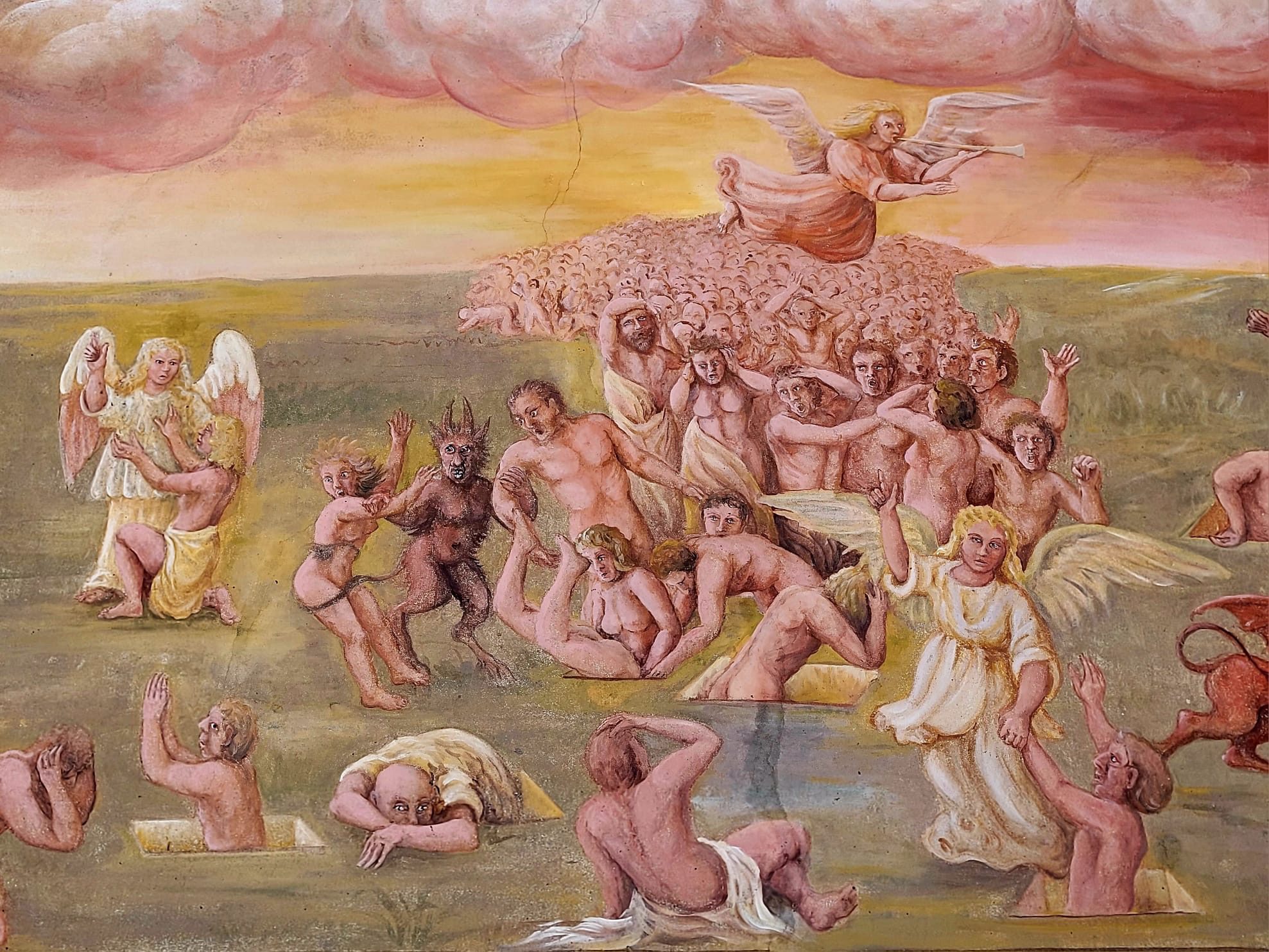

Another painting worth seeing can be found on the church's warrior chapel. The depiction of the Last Judgement with saints, angels and devils leading the good citizens to paradise after their earthly life, while the bad are dragged into the pit of hell, is a wonderful example of the religious imagination of the Baroque Counter-Reformation. The church tower, crowned by a pointed spire, is the highest in the city of Innsbruck.

Tyrol in the hands of farmers

Die Identifikation mit dem Bauernstand ist in Tirol noch immer sehr hoch. Obwohl heute weniger als 2% der Bevölkerung von der Landwirtschaft leben, schaffen es Bauern über reges Vereinsleben, geschickte Selbstdarstellung und politische Vorfeldstrukturen eine überdurchschnittliche Repräsentation in der Gesellschaft zu haben. Das war nicht immer so. Über Jahrhunderte arbeitete der allergrößte Teil der Menschen in der Landwirtschaft, Bauern hatten aber kaum politisches Gewicht. Die Grundherren besaßen nicht nur Grund und Boden, sondern hatten auch Herrschaftsgewalt über die Builders selbst. An ein eigenständiges Agieren der Untertanen als aktive Teilnehmer des Wirtschaftskreislaufes war nicht zu denken. Regelmäßig wurde die Pacht in Form von Naturalien eingetrieben. Der lokale Kleinadel verwaltete die Bauernschaften innerhalb seines Territoriums und entrichtete seinerseits seine Abgaben an den Landesfürsten oder den Bischof. Erst nach und nach entwickelte sich das Bauernwesen in den stolzen Stand, den es bis heute darstellt.

There were three types of relationship between peasants and landlords. Throughout the Middle Ages, the Leibgeding common. Peasants worked on the manorial estates as serfs. This serfdom could go so far that marriage, property, mobility and other matters of personal life could not be freely decided. This form was already a thing of the past in the vast majority of Tyrol in the early modern period.

The second form, the Free pencilThe tenancy was a lease of a farm for a certain period of time, usually one year. It was usually extended, as both landlords and farmers benefited from a constant business relationship, similar to employers and employees today. However, the subjects did not have a legal right to remain on their estate, nor were there any documents that contractually regulated the legal transaction. Oral contracts were subject to customary law and tradition. The landlord could move his builders back and forth within his estates or hire them out completely. pinThey were thrown out. If the farm was passed on from a farmer to his son within the family with the landlord's consent, an honour was due, a payment of up to 10% of the value of the farm.

The third and most modern form was the Inheritance loan. Even with this form of lease, the land remained the property of the landlord, a Staking was no longer so easily possible. Heirs paid less interest than Pen people. In autumn, either on St Gall's Day (16 October) or on St Martin's Day (11 November), the farmers had to pay their rent in hereditary loans, which shifted more and more from payments in kind to the sounding of coins. Farmers were able to expand their farms through acquisitions or skilful marriage policies. Farms were inherited within the family. Old farmers who sold their property with the warm handThe heirs, who were handed over during their lifetime, retained the right to live at the court and were paid an agreed Ausgedinge supplied.

Peasant inheritance law varied from region to region. In the North Tyrolean Oberland and in South Tyrol, the Real division in other words, the farm was divided up among all the heirs. This automatically led to a fragmentation of the estates and lower profitability. In the Innsbruck region and the lowlands, on the other hand, the Division of inheritance common practice. With few exceptions, the eldest child inherited the entire farm in order to maintain the structure. The siblings of the sole heir usually had no choice but to leave. They had to earn a living as servants, craftsmen, farmhands and maidservants. When Söllhäuslerpeople with a small house and perhaps a garden but no land to speak of, they belonged to the Pofelwhich was made up of innkeepers, travelling folk, prostitutes, servants, maidservants and beggars. In the event of illness or destitution, they had claims against the heir and could be accommodated on the farm for a certain period of time. Depending on the value of the farm, the heir's siblings were also entitled to interest, although this was usually little or nothing. Even back then, farmers were skilful at minimising the book value of their estates.

In the 15th century, the rules of the game began to change. The lesser nobility had always been a thorn in the side of the sovereign princes as an intermediate lordship with its own jurisdiction. Step by step, a modern state began to emerge at the end of the Middle Ages. Monarchs and the high aristocracy wanted to exercise direct rule over their subjects. Although the estate-based society and birthright were not affected by this development, the role of the lesser nobility changed. They went from being lords with power of disposal over their subjects to administrators of their estates and organisers of national defence on behalf of the respective prince.

In order to minimise the influence of the lesser nobility, Frederick IV stipulated in his Land Ordinance of 1404 that the legal recognition of the Inheritance loan fixed. With the exception of the territories of the prince-bishops of Trento and Brixen in Tyrol, this form of granting agricultural estates subsequently prevailed over the Free pencil through. Legal disputes between peasants and landlords had to be negotiated before the sovereign. With this daring political act, Frederick bought the immediate affection and loyalty of his subjects in order to gain direct access to military manpower and tax payments. The peasants had the advantage of no longer being at the mercy of their landlords.

With the Inheritance loan farmers became entrepreneurs of sorts, participating in early capitalism as market players. Although they were still subject to the whims of nature and the political climate, such as wars or customs regulations, they now had the opportunity to rise from the subsistence level of previous centuries. After paying the tithe and providing for the household, they sold their goods on the market. Motivated and hard-working farmers were able to build up a certain level of prosperity. As a result of the social and economic changes that took place in Innsbruck from the 15th century when it became a royal seat and in the towns of Hall and Schwaz as a result of mining, the farmers in the neighbouring villages also benefited from the upturn. The people who worked as civil servants at court or in the New Industry The people who were employed in mining formed a middle class with greater purchasing power. The demand for meat increased. This in turn led to a change in agriculture. Farmers discovered livestock farming as a more lucrative source of income than arable farming.

Inflation following the discovery of the New World and the financial upheavals of the 16th century also reduced the amount of rent that farmers had to pay as a monetary value. Smaller farmers, who received their farms as freeholds and had to pay their dues in kind, suffered from the devaluation of money, while large farms benefited from it.

These developments led to new social relationships on the farms themselves and to greater differences within the peasantry. Peasants presided over their servants in all matters, similar to the Pater Familias of the extended family in ancient Rome. Life on the estates had little to do with the wholesome family life that is often propagated today as a traditional Tyrolean lifestyle. Rather, they were clan-like extended family groups that were under the strict regime of the farmer in everyday life: He determined the working day, food, lodging, meagre leisure time and personal relationships. Clear hierarchies developed in the villages. Hereditary farmers had higher status than Pen farmers. Large farmers had more prestige than small farmers. They often presided over their villages. Particularly successful and loyal farmers were awarded their own family coat of arms by the prince and were honoured as Peasant nobility. Diese Strukturen hielten sich am Land bis weit ins 19. Jahrhundert, in abgelegeneren Regionen des Landes bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. Bei Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkrieges waren in Tirol noch immer mehr als 50% in der Landwirtschaft tätig. Die schönen Bauernhäuser in Hötting, Wilten Pradl und Amras, auf deren Fassaden stolz die Familienwappen und der Hinweis auf den Status als Hereditary farm are testimony to the rise of the peasantry in the early modern period.

Philippine Welser: Klein Venedig, Kochbücher und Kräuterkunde

Philippine Welser (1527 - 1580) was the wife of Archduke Ferdinand II and one of Innsbruck's most popular rulers. The Welsers were one of the wealthiest families of their time. Their uncle Bartholomäus Welser was similarly wealthy to Jakob Fugger and also came from the class of merchants and financiers who had acquired enormous wealth around 1500. The pillars of this wealth were the spice trade with India and the mining and metal trade with the American colonies. Welser had also granted loans to the Habsburgs. Instead of paying off the loans, Emperor Charles V pledged some of the newly annexed lands in America to the Welser family, who in return received the land as a colony. Klein-VenedigVenezuela, with fortresses and settlements. They organised expeditions to discover the legendary land of gold El Dorado to discover. In order to get as much as possible out of their fiefdom, they established trading posts to participate in the profitable transatlantic slave trade between Europe, West Africa and America. Although Charles V prohibited trade with indigenous people from South Africa after 1530, the use of African slaves on the plantations and in the mines was not covered by this regulation. The brutal behaviour of the Welser led to complaints at the imperial court in 1546, where they were denied the fiefdom for Klein-Venedig was subsequently withdrawn. However, their trade relations remained intact.

Ferdinand and Philippine met at a carnival ball in Pilsen. The Habsburg fell head over heels in love with the wealthy woman from Augsburg and married her. Nobody in the House of Habsburg was particularly pleased about the couple's secret marriage, even though the business relationships between the aristocrats and the newly rich Augsburg merchants were already several decades old and the Welser's money could be put to good use. Marriages between commoners and aristocrats were considered scandalous and not befitting their status, despite their wealth. The emperor only recognised the marriage after the couple had asked for forgiveness for their marriage and pledged themselves to eternal secrecy. The children of the morganatic marriage were therefore excluded from the succession.

Philippine galt als überaus schön. Ihre Haut sei laut Zeitzeugen so zart gewesen, „man hätte einen Schluck Rotwein durch ihre Kehle fließen sehen können". Ferdinand had Ambras Castle remodelled into its present form for his beloved wife. His brother Maximilian even said that "Ferdinand verzaubert sai" by the beautiful Philippine Welser when Ferdinand withdrew his troops during the Turkish war to go home to his wife. The epilogue is less flattering "...I wanted the brekin to be in a sakh and what not. God forgive me."

Philippine Welser's passion was cooking. There is still a collection of recipes in the Austrian National Library today. In the Middle Ages and early modern times, the art of cookery was practised exclusively by the wealthy and aristocrats, while the vast majority of subjects had to eat whatever was available. The Middle Ages and modern times, in fact all people up until the 1950s, lived with a permanent lack of calories. Whereas today we eat too much and get ill as a result, our ancestors suffered from illnesses caused by malnutrition. Fruit was just as rare on the menu as meat. The food was monotonous and hardly flavoured. Spices such as exotic pepper were luxury goods that ordinary people could not afford. While the diet of the ordinary citizen was a dull affair, where the main aim was to get the calories for the daily work as efficiently as possible, the attitude towards food and drink began to change in Innsbruck under Ferdinand II and Philippine Welser. The court had contributed to a certain cultivation of manners and customs in Innsbruck since Frederick IV, and Philippine Welser and Ferdinand took this development to the extreme at Ambras Castle and Weiherburg Castle. The banquets they organised were legendary and often degenerated into orgies.

Herbalism was her second hobbyhorse. Philippine Welser described how to use plants and herbs to alleviate physical ailments of all kinds. "To whiten and freshen the teeth and kill the worms in them: Take rosemary wood and burn it to charcoal, crush it all to powder, bind it in a silken cloth and rub the teeth with itwas one of her tips for a healthy and cultivated existence. She had a herb garden created at Ambras Castle in Innsbruck for her hobby and her studies.

According to reports of the time, she was very popular among the Tyrolean population, as she took great care of the poor and needy. The care of the needy, led by the town council and sponsored by wealthy citizens and aristocrats, was not a speciality at the time, but common practice. Closer to salvation in the next life than through Christian charity, Caritasyou could not come.

, konnte man nicht kommen. Ihre letzte Ruhe fand Philippine Welser nach ihrem Tod 1580 in der Silbernen Kapelle in der Innsbrucker Hofkirche. Gemeinsam mit ihren als Säugling verstorbenen Kindern und Ferdinand wurde sie dort begraben. Unterhalb des Schloss Ambras erinnert die Philippine-Welser-Straße an sie.

Believe, Church and Power

The abundance of churches, chapels, crucifixes and murals in public spaces has a peculiar effect on many visitors to Innsbruck from other countries. Not only places of worship, but also many private homes are decorated with depictions of the Holy Family or biblical scenes. The Christian faith and its institutions have characterised everyday life throughout Europe for centuries. Innsbruck, as the residence city of the strictly Catholic Habsburgs and capital of the self-proclaimed Holy Land of Tyrol, was particularly favoured when it came to the decoration of ecclesiastical buildings. The dimensions of the churches alone are gigantic by the standards of the past. In the 16th century, the town with its population of just under 5,000 had several churches that outshone every other building in terms of splendour and size, including the palaces of the aristocracy. Wilten Monastery was a huge complex in the centre of a small farming village that was grouped around it. The spatial dimensions of the places of worship reflect their importance in the political and social structure.

For many Innsbruck residents, the church was not only a moral authority, but also a secular landlord. The Bishop of Brixen was formally on an equal footing with the sovereign. The peasants worked on the bishop's estates in the same way as they worked for a secular prince on his estates. This gave them tax and legal sovereignty over many people. The ecclesiastical landowners were not regarded as less strict, but even as particularly demanding towards their subjects. At the same time, it was also the clergy in Innsbruck who were largely responsible for social welfare, nursing, care for the poor and orphans, feeding and education. The influence of the church extended into the material world in much the same way as the state does today with its tax office, police, education system and labour office. What democracy, parliament and the market economy are to us today, the Bible and pastors were to the people of past centuries: a reality that maintained order. To believe that all churchmen were cynical men of power who exploited their uneducated subjects is not correct. The majority of both the clergy and the nobility were pious and godly, albeit in a way that is difficult to understand from today's perspective.

Unlike today, religion was by no means a private matter. Violations of religion and morals were tried in secular courts and severely penalised. The charge for misconduct was heresy, which encompassed a wide range of offences. Sodomy, i.e. any sexual act that did not serve procreation, sorcery, witchcraft, blasphemy - in short, any deviation from the right belief in God - could be punished with burning. Burning was intended to purify the condemned and destroy them and their sinful behaviour once and for all in order to eradicate evil from the community.

For a long time, the church regulated the everyday social fabric of people down to the smallest details of daily life. Church bells determined people's schedules. Their sound called people to work, to church services or signalled the death of a member of the congregation. People were able to distinguish between individual bell sounds and their meaning. Sundays and public holidays structured the time. Fasting days regulated the diet. Family life, sexuality and individual behaviour had to be guided by the morals laid down by the church. The salvation of the soul in the next life was more important to many people than happiness on earth, as this was in any case predetermined by the events of time and divine will. Purgatory, the last judgement and the torments of hell were a reality and also frightened and disciplined adults.

While Innsbruck's bourgeoisie had been at least gently kissed awake by the ideas of the Enlightenment after the Napoleonic Wars, the majority of people in the surrounding communities remained attached to the mixture of conservative Catholicism and superstitious popular piety.

Faith and the church still have a firm place in the everyday lives of Innsbruck residents, albeit often unnoticed. The resignations from the church in recent decades have put a dent in the official number of members and leisure events are better attended than Sunday masses. However, the Roman Catholic Church still has a lot of ground in and around Innsbruck, even outside the walls of the respective monasteries and educational centres. A number of schools in and around Innsbruck are also under the influence of conservative forces and the church. And anyone who always enjoys a public holiday, pecks one Easter egg after another or lights a candle on the Christmas tree does not have to be a Christian to act in the name of Jesus disguised as tradition.

March 1848... and what it brought

The year 1848 occupies a mythical place in European history. Although the hotspots were not to be found in secluded Tyrol, but in the major metropolises such as Paris, Vienna, Budapest, Milan and Berlin, even in the Holy Land however, the revolutionary year left its mark. In contrast to the rural surroundings, an enlightened educated middle class had developed in Innsbruck. Enlightened people no longer wanted to be subjects of a monarch or sovereign, but citizens with rights and duties towards the state. Students and freelancers demanded political participation, freedom of the press and civil rights. Workers demanded better wages and working conditions. Radical liberals and nationalists in particular even questioned the omnipotence of the church.

In March 1848, this socially and politically highly explosive mixture erupted in riots in many European cities. In Innsbruck, students and professors celebrated the newly enacted freedom of the press with a torchlight procession. On the whole, however, the revolution proceeded calmly in the leisurely Tyrol. It would be foolhardy to speak of a spontaneous outburst of emotion; the date of the procession was postponed from 20 to 21 March due to bad weather. There were hardly any anti-Habsburg riots or attacks; a stray stone thrown into a Jesuit window was one of the highlights of the Alpine version of the 1848 revolution. The students even helped the city magistrate to monitor public order in order to show their gratitude to the monarch for the newly granted freedoms and their loyalty.

The initial enthusiasm for bourgeois achievements was quickly replaced by German nationalist, patriotic fervour in Innsbruck. On 6 April 1848, the German flag was waved by the governor of Tyrol during a ceremonial procession. A German flag was also raised on the city tower. Tricolour was hoisted. While students, workers, liberal-nationalist-minded citizens, republicans, supporters of a constitutional monarchy and Catholic conservatives disagreed on social issues such as freedom of the press, they shared a dislike of the Italian independence movement that had spread from Piedmont and Milan to northern Italy. Innsbruck students and marksmen marched to Trentino with the support of the k.k. The Innsbruck students and riflemen moved into Trentino to nip the unrest and uprisings in the bud. Well-known members of this corps were Father Haspinger, who had already fought with Andreas Hofer in 1809, and Adolf Pichler.

The city of Innsbruck, as the political and economic centre of the multinational crown land of Tyrol and home to many Italian speakers, also became the arena of this nationality conflict. Combined with copious amounts of alcohol, anti-Italian sentiment in Innsbruck posed more of a threat to public order than civil liberties. A quarrel between a German-speaking craftsman and an Italian-speaking Ladin got so heated that it almost led to a pogrom against the numerous businesses and restaurants owned by Italian-speaking Tyroleans.

The relative tranquillity of Innsbruck suited the imperial house, which was under pressure. When things did not stop boiling in Vienna even after March, Emperor Ferdinand fled to Tyrol in May. According to press reports from this time, he was received enthusiastically by the population.

"Wie heißt das Land, dem solche Ehre zu Theil wird, wer ist das Volk, das ein solches Vertrauen genießt in dieser verhängnißvollen Zeit? Stützt sich die Ruhe und Sicherheit hier bloß auf die Sage aus alter Zeit, oder liegt auch in der Gegenwart ein Grund, auf dem man bauen kann, den der Wind nicht weg bläst, und der Sturm nicht erschüttert? Dieses Alipenland heißt Tirol, gefällts dir wohl? Ja, das tirolische Volk allein bewährt in der Mitte des aufgewühlten Europa die Ehrfurcht und Treue, den Muth und die Kraft für sein angestammtes Regentenhaus, während ringsum Auflehnung, Widerspruch. Trotz und Forderung, häufig sogar Aufruhr und Umsturz toben; Tirol allein hält fest ohne Wanken an Sitte und Gehorsam, auf Religion, Wahrheit und Recht, während anderwärts die Frechheit und Lüge, der Wahnsinn und die Leidenschaften herrschen anstatt folgen wollen. Und während im großen Kaiserreiche sich die Bande überall lockern, oder gar zu lösen drohen; wo die Willkühr, von den Begierden getrieben, Gesetze umstürzt, offenen Aufruhr predigt, täglich mit neuen Forderungen losgeht; eigenmächtig ephemere- wie das Wetter wechselnde Einrichtungen schafft; während Wien, die alte sonst so friedliche Kaiserstadt, sich von der erhitzten Phantasie der Jugend lenken und gängeln läßt, und die Räthe des Reichs auf eine schmähliche Weise behandelt, nach Laune beliebig, und mit jakobinischer Anmaßung, über alle Provinzen verfügend, absetzt und anstellt, ja sogar ohne Ehrfurcht, den Kaiaer mit Sturm-Petitionen verfolgt; während jetzt von allen Seiten her Deputationen mit Ergebenheits-Addressen mit Bittgesuchen und Loyalitätsversicherungen dem Kaiser nach Innsbruck folgen, steht Tirol ganz ruhig, gleich einer stillen Insel, mitten im brausenden Meeressturme, und des kleinen Völkchens treue Brust bildet, wie seine Berge und Felsen, eine feste Mauer in Gesetz und Ordnung, für den Kaiser und das Vaterland."

In June, Franz Josef also stopped off at the Hofburg on his way back from the battlefields of northern Italy instead of travelling directly to Vienna. Innsbruck was once again the royal seat, if only for one summer.

In the same year, Ferdinand handed over the throne to Franz Josef I. In July 1848, the first parliamentary session was held in the Court Riding School in Vienna. A first constitution was enacted. However, the monarchy's desire for reform quickly waned. The new parliament was an imperial council, it could not pass any binding laws, the emperor never attended it during his lifetime and did not understand why the Danube Monarchy, as a divinely appointed monarchy, needed this council.

Nevertheless, the liberalisation that had been gently set in motion took its course in the cities. Innsbruck was given the status of a town with its own statute. Innsbruck's municipal law provided for a right of citizenship that was linked to ownership or the payment of taxes, but legally guaranteed certain rights to members of the community. Birthright citizenship could be acquired by birth, marriage or extraordinary conferment and at least gave male adults the right to vote at municipal level. If you got into financial difficulties, you had the right to basic support from the town.

On 2 June 1848, the first issue of the liberal and Greater German-minded Innsbrucker Zeitungfrom which the above article on the emperor's arrival in Innsbruck is taken. Conservatives, on the other hand, read the Volksblatt for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. Moderate readers who favoured a constitutional monarchy preferred to consume the Bothen for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. However, the freedom of the press soon came to an end. The previously abolished censorship was reintroduced in parts. Newspaper publishers had to undergo some harassment by the authorities. Newspapers were not allowed to write against the state government, monarchy or church.

"Anyone who, by means of printed matter, incites, instigates or attempts to incite others to take action which would bring about the violent separation of a part from the unified state... of the Austrian Empire... or the general Austrian Imperial Diet or the provincial assemblies of the individual crown lands.... Imperial Diet or the Diet of the individual Crown Lands... violently disrupts... shall be punished with severe imprisonment of two to ten years."

After Innsbruck officially replaced Meran as the provincial capital in 1849 and thus finally became the political centre of Tyrol, political parties were formed. From 1868, the liberal and Greater German orientated party provided the mayor of the city of Innsbruck. The influence of the church declined in Innsbruck in contrast to the surrounding communities. Individualism, capitalism, nationalism and consumerism stepped into the breach. New worlds of work, department stores, theatres, cafés and dance halls did not supplant religion in the city either, but the emphasis changed as a result of the civil liberties won in 1848.

Perhaps the most important change to the law was the Basic relief patent. In Innsbruck, the clergy, above all Wilten Abbey, held a large proportion of the peasant land. The church and nobility were not subject to taxation. In 1848/49, manorial rule and servitude were abolished in Austria. Land rents, tithes and roboters were thus abolished. The landlords received one third of the value of their land from the state as part of the land relief, one third was regarded as tax relief and one third of the relief had to be paid by the farmers themselves. The farmers could pay off this amount in instalments over a period of twenty years.

The after-effects can still be felt today. The descendants of the then successful farmers enjoy the fruits of prosperity through inherited land ownership, which can be traced back to the land relief of 1848, as well as political influence through land sales for housing construction, leases and public sector redemptions for infrastructure projects. The land-owning nobles of the past had to resign themselves to the ignominy of pursuing middle-class labour. The transition from birthright to privileged status within society was often successful thanks to financial means, networks and education. Many of Innsbruck's academic dynasties began in the decades after 1848.

The hitherto unknown phenomenon of leisure time emerged, albeit sparsely for the most part, and, together with disposable income, favoured hobbies for a larger number of people. Civil organisations and clubs, from reading circles to singing societies, fire brigades and sports clubs, were founded. The revolutionary year also manifested itself in the cityscape. Parks such as the English Garden at Ambras Castle were no longer the exclusive preserve of the aristocracy, but served as recreational areas for the citizens to escape their cramped existence. In St. Nikolaus, on the site of the raft landing stage on the Inn, the Waltherpark.