Tiroler Landestheater & Kongresshaus

Rennweg 3

Worth knowing

The area between the Hofburg and the Hofgarten was already used for entertainment during the time of Emperor Maximilian. Competitions and tournaments of all kinds took place at the racecourse. Innsbruck’s Renaissance prince preferred less sporting but more culturally appealing activities. Under Ferdinand II, the first city theatre was built in 1581 according to plans by court architect Alberto Lucchese, called the Comedihaus. The name is misleading. The plays performed under Jesuit direction were usually lengthy dramas in Latin, based on biblical themes or, in true Renaissance spirit, on antiquity. Theatre was intended to prepare the audience for confessional resistance against the looming coarsening brought by Protestantism and to maintain morale in the fight against the Ottoman threat to the Habsburg realm. For Emperor Ferdinand’s wedding in 1622, a play was staged with the memorable title: “Action of Ovinio Gallicono, who once defeated the Scythians after first converting to Christianity and thus winning the hand of Constantine’s daughter.” Those who preferred secular entertainment were not left out: alongside plays, dressage riding and water shows were also possible. Not only classical culture but also the principle of “bread and circuses” enjoyed great popularity during the Renaissance.

In 1630, Prince Leopold V converted a ball house into a court theatre. He and his wife Claudia de Medici, educated contemporaries of the 17th century, valued art and culture. Their residence city was to be up to date. Until then, theatres were usually travelling institutions moving from town to town, or local universities and grammar schools organised performances. Now, a permanent team was to amuse, educate, and instruct the court as needed. The court theatre was one of the first permanent opera and theatre houses in the Holy Roman Empire. The Jesuits and their pupils still led the productions, but the highlights were the Innsbruck horse ballet and the ladies’ ballet, which the princely couple even exported as cultural showcases to the imperial court in Vienna. The lavish spectacle did not last long, as financial hardship after the Thirty Years’ War was too great. Innsbruck was a small town with about 5,000 inhabitants, most of whom were neither interested in Jesuit baroque performances nor could afford to attend. In 1653, the oversized city theatre moved to the site of today’s Tyrolean State Theatre, opposite the Hofgarten. Christoph Gumpp planned to convert one of the former ball game houses into a smaller but more modern Comedihaus in Venetian style with only 1,000 seats.

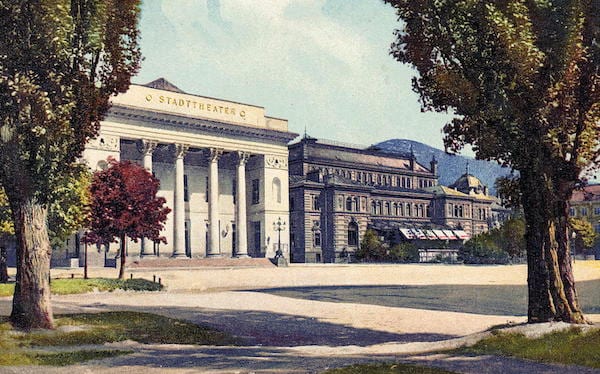

Im 18. Jahrhundert ging die Zeit der exklusiv höfischen Theaterkultur zu Ende. Mit der Verbürgerlichung der Gesellschaft nahm das Showbusiness eine öffentliche Rolle ein. In Innsbruck war die Hochkultur und deren Deutung immer von den Macht- und Herrschaftsverhältnissen geprägt. 1765 unter Maria Theresia wurde das „Hoftheater" and under their son Josef, a supporter of the modern nation state, it was renovated into the Nationaltheater. In 1805, under Bavarian foreign rule, it was the "Königlich-Bayrische Hof-Nationaltheater“. During the period of nationalisation following the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire, the Hoftheater zum austrianisierten Nationaltheater. Nach den napoleonischen Kriegen gierten die kunstsinnigen Bürger Innsbrucks nach Unterhaltung, wie sie international üblich war. Dafür musste das alte Nationaltheater modern aus- und umgebaut werden. Das Landestheater in seinem aktuellen Aussehen wurde im 19. Jahrhundert vom italienischen Architekten Giuseppe Segusini (1801 – 1876) geplant. Segusini kam im von Napoleon besetzten Norditalien zur Welt. Seine Ausbildung absolvierte er während der habsburgischen Herrschaft in Venedig an der Accademia di Belle Arti. 1840 legte er einen Plan zum Umbau des Innsbrucker Hoftheaters vor. Der klassizistische Bau entstand vier Jahre später vor einem ähnlichen gesellschaftlichen Hintergrund wie das Ferdinandeum, für dessen Neubau Segusini ebenfalls Pläne vorlegte, aber nicht zum Zug kam. Ein großer Teil der Kosten wurde ganz im Geist der Zeit vom eigens dafür gegründeten Theaterverein der Stadt übernommen. Die Neueröffnung in seinem jetzigen Aussehen erfolgte am 19. April 1846, dem Geburtstag Kaisers Ferdinand I., einem der Stadt Innsbruck besonders gewogenen Monarchen. Die Form des Gebäudes ähnelt einem römischen Triumphbogen. Der wuchtige Eingangsbereich über Treppen wird von mächtigen Säulen gestützt. Heute wirkt das altehrwürdige Landestheater neben dem wuchtigen und modernen House of Music beinahe etwas verloren. Im Nationalsozialismus wurde aus dem Nationaltheater das „Reichsgautheater“, der Platz davor erhielt den Namen Adolf Hitler Square. Nach dem Krieg wurde es zum Tiroler Landestheater.

The former ball house on the opposite side of the street, today’s Congress Centre, served as the court riding school during the years when Tyrol had a sovereign prince. In 1776, in the spirit of rationalisation, it became a customs house. The centralisation under Maria Theresa and Joseph II required new infrastructure to accommodate officials for taxation. The name Dogana, Italian for customs, derives from this use. In the 19th century, the former administrative building hosted fairs and exhibitions, such as the Tyrolean State Exhibition of 1893. During the first air raids on Innsbruck in 1944, the Dogana suffered considerable damage. Unlike destroyed houses and churches, the congress centre was not high on the list of system-relevant buildings. For 25 years, the remains of the Dogana decayed to the foundations before work began on the ruin in the city centre. According to plans by architect Hubert Prachensky, a cubic building in the Brutalist style was constructed between 1970 and 1973, almost simultaneously with the four Mariahilfpark residential blocks. Both inside and outside, the congress centre appears bulky and blocky, softened only by newer building sections. Modern artworks inside include pieces by Rudi Wach, who also created the crucifix on the Inn Bridge. Since 2007, the new valley station of the Hungerburgbahn has been located next to the congress centre. In the spirit of a modern gladiator fight, which could have taken place at the racecourse in Maximilian’s time, the finish area between the theatre and the congress centre hosted the biggest sporting event since the Olympic Games with the 2018 Cycling World Championships.

Ferdinand II: Principe and Renaissance prince

Archduke Ferdinand II of Austria (1529 - 1595) is one of the most colourful figures in Tyrolean history. His father, Emperor Ferdinand I, gave him an excellent education. He grew up at the Spanish court of his uncle Emperor Charles V. The years in which Ferdinand received his schooling were the early years of Jesuit influence at the Habsburg courts. The young statesman was brought up entirely in the spirit of pious humanism. This was complemented by the customs of the Renaissance aristocracy. At a young age, he travelled through Italy and Burgundy and had become acquainted with a lifestyle at the wealthy courts there that had not yet established itself among the German aristocracy. Ferdinand was what today would be described as a globetrotter, a member of the educated elite or a cosmopolitan. He was considered intelligent, charming and artistic. Among his less eccentric contemporaries, Ferdinand enjoyed a reputation as an immoral and hedonistic libertine. Even during his lifetime, he was rumoured to have organised debauched and immoral orgies.

Ferdinand's father divided his kingdom between his sons. Maximilian II, who was rightly suspected of heresy and adherence to Protestant doctrines by his parents, inherited Upper and Lower Austria as well as Bohemia and Hungary. Ferdinand's younger brother Charles ruled in Inner Austria, i.e. Carinthia, Styria and Carniola. The middle child received Tyrol, which at that time extended as far as the Engadine, and the fragmented Habsburg Forelands in the west of the central European possessions. Ferdinand took over the Tyrol as sovereign in turbulent times. He had already spent several years in Innsbruck in his youth. The mines in Schwaz began to become unprofitable due to the cheap silver from America. The flood of silver from the Habsburg possessions in New Spain on the other side of the Atlantic led to inflation.

However, these financial problems did not stop Ferdinand from commissioning personal and public infrastructure. Innsbruck benefited enormously, both economically and culturally, from the fact that after years without a sovereign prince, it was now once again the centre of a ruler. Ferdinand's archducal presence attracted the aristocracy and civil servants back to Innsbruck after the decades of neglect following Maximilian's death. By the late 1560s, the administration had grown back to 1000 people, who fuelled the local economy with their money. Bakers, butchers and inns flourished again after a few barren years. At the end of the 16th century, Innsbruck had an above-average number of innkeepers compared to other towns, who earned an above-average amount of money from merchants, guests and travellers passing through. Wine houses were not only inns, but also storage and trading centres.

The Italian cities of Florence, Venice and Milan were trendsetters in terms of culture, art and architecture. Ferdinand's Tyrolean court was to be in no way inferior to them. Gone were the days when Germans were considered uncivilised in the more beautiful cities south of the Alps, barbaric or even as Pigs were labelled. To this end, he had Innsbruck remodelled in the spirit of the Renaissance. In keeping with the trend of the time, he imitated the Italian aristocratic courts. Court architect Giovanni Lucchese assisted him in this endeavour. Ferdinand spent a considerable part of his life at Ambras Castle near Innsbruck, where he amassed one of the most valuable collections of works of art and armour in the world. Ferdinand transformed the castle above the village of Amras into a modern court. His parties, masked balls and parades were legendary. During the wedding of a nephew, he had 1800 calves and 130 oxen roasted. Wine is said to have flowed from the wells instead of water for 10 days.

But Ambras Castle was not the end of Innsbruck's transformation. To the west of the city, an archway still reminds us of the Tiergartena hunting ground for Ferdinand, including a summer house also designed by Lucchese. In order for the prince to reach his weekend residence, a road was laid in the marshy Höttinger Au, which formed the basis for today's Kranebitter Allee. The Lusthaus was replaced in 1786 by what is now known as the Pulverturm The new building, which houses part of the sports science faculty of the University of Innsbruck, replaced the well-known building. The princely sport of hunting was followed in the former Lusthauswhich was the Powder Tower. In the city centre, he had the princely Comedihaus on today's Rennweg. In order to improve Innsbruck's drinking water supply, the Mühlauerbrücke bridge was built under Ferdinand to lay a water pipeline from the Mühlaubach stream into the city centre. The Jesuits, who had arrived in Innsbruck shortly before Ferdinand took office to make life difficult for troublesome reformers and church critics and to reorganise the education system, were given a new church in Silbergasse. Numerous new buildings such as the Jesuit, Franciscan, Capuchin and Servite monasteries boosted trade and the construction industry.

The new religious orders supported Ferdinand's focus on the confessional orientation of his flock. In his Tyrolean provincial ordinance issued in 1573, he not only put a stop to fornication, swearing and prostitution, but also obliged his subjects to lead a God-fearing, i.e. Catholic, lifestyle. The „Prohibition of sorcery and disbelieving warfare" prohibited any deviation from the true faith on pain of imprisonment, corporal punishment and expropriation. Jews had to wear a clearly visible ring of yellow fabric on the left side of their chest at all times. At the same time, Ferdinand brought a Jewish financier to Innsbruck to handle the money transactions for the elaborate farm management. Samuel May and his family lived in the city as princely patronage Jews. Daniel Levi delighted Ferdinand with dancing and harp playing at the theatre and Elieser Lazarus looked after his health as court physician.

Fleecing the population, living in splendour, tolerating Protestantism among his important advisors and at the same time fighting Protestantism among the people was no contradiction for the trained Renaissance prince. Already at the age of 15, he marched under his uncle Charles V in the Schmalkaldic War into battle against the enemies of the Roman Church. As a sovereign, he saw himself as Advocatus Ecclesiae (note: representative of the church) in a confessional absolutist sense, who was responsible for the salvation of his subjects. Coercive measures, the foundation of churches and monasteries such as the Franciscans and the Capuchins in Innsbruck, improved pastoral care and the staging of Jesuit theatre plays such as "The beheading of John" were the weapons of choice against Protestantism. Ferdinand's piety was not artificial, but like most of his contemporaries, he managed to adapt flexibly to the situation.

Ferdinand's politics were suitably influenced by the Italian avant-garde of the time. Machiavelli wrote his work "Il Principe", which stated that rulers were allowed to do whatever was necessary for their success, even if they were incapable of being deposed. Ferdinand II attempted to do justice to this early absolutist style of leadership and issued his Tyrolean Provincial Code A modern set of legal rules by the standards of the time. For his subjects, this meant higher taxes on their earnings as well as extensive restrictions on mountain pastures, fishing and hunting rights. The miners, mining entrepreneurs and foreign trading companies with their offices in Innsbruck also drove up food prices. It could be summarised that Ferdinand enjoyed the exclusive pleasure of hunting on his estates, while his subjects lived at subsistence level due to increasing burdens, prices and game damage.

His relationship life was eccentric for a member of the high aristocracy. Ferdinand's first "semi-wild marriage" was to the commoner Philippine Welser. After his wife #1 died, Ferdinand married the devout Anna Caterina Gonzaga, a 16-year-old Princess of Mantua, at the age of 53. However, it seems that the two did not feel much affection for each other, especially as Anna Caterina was a niece of Ferdinand. The Habsburgs were less squeamish about marriages between relatives than they were about the marriage of a nobleman to a commoner. However, he was also "only" able to father three daughters with her. Ferdinand's final resting place was in the Silver Chapel with his first wife Philippine Welser.

Leopold V & Claudia de Medici: Glamour and splendour in Innsbruck

The most important princely couple for the Baroque face of Innsbruck ruled Tyrol during the period in which the Thirty Years' War devastated Europe. The Habsburg Leopold (1586 - 1632) to lead the princely affairs of state in the Upper Austrian regiment in Tyrol and the foothills. He had enjoyed a classical education under the wing of the Jesuits. He studied philosophy and theology in Graz and Judenburg in order to prepare himself for the clerical realm of power politics, a common career path for later-born sons who had little chance of ascending to secular thrones. Leopold's early career in the church's power structure epitomised everything that Protestants and church reformers rejected about the Catholic Church. At the age of 12, he was elected Bishop of Passau, and at thirteen he was appointed coadjutor of the diocese of Strasbourg in Lorraine. However, he never received ecclesiastical ordination. His prince-bishop was responsible for his spiritual duties. He was a passionate politician, travelled extensively between his dioceses and took part on the imperial side in the conflict between Rudolf II and Matthias, the model for Franz Grillparzer's "Fraternal strife in the House of Habsburg". These agendas, which were not necessarily an honour for a churchman, were intended to keep Leopold's chances of becoming a secular prince alive.

This opportunity came when the unmarried Maximilian III died childless in 1618. At the behest of his brother, Leopold acted as the Habsburg Governor and regent of these Upper and Vorderösterreichische, also Mitincorpierter Leuth and Lannde. In his first years as regent, he continued to commute between his bishoprics in southern and western Germany, which were threatened by the turmoil of the Thirty Years' War. The ambitious power politician was probably satisfied with his exciting life in the midst of high politics, but not with his status as gubernator. He wanted the title of Prince Regnant along with homage and dynastic hereditary rights. He lacked a suitable bride, time and money for the title of prince and to set up a court. The costly disputes in which he was involved had emptied Leopold's coffers.

The money came with the bride and with it came time. Claudia de Medici (1604 - 1648) from the rich Tuscan family of merchants and princes was chosen to bring dynastic delights to the future sovereign, who was already approaching 40. Claudia had already been promised to the Duke of Urbino as a child, whom she married at the age of 17 despite a request from Emperor Ferdinand II. After two years of marriage, her husband died. The ties with the Habsburgs were still there. The two dynasties had been closely intertwined since the marriage of Francesco de Medici to Joan of Habsburg, a daughter of Ferdinand I. at the latest. Leopold and Claudia were also a Perfect Match of title, power, baroque piety and money. Leopold's sister Maria Magdalena had landed in Florence as Grand Duchess of Tuscany by marriage and sent her brother a painted portrait of the young widow Claudia with the accompanying words that she "beautiful in face, body and virtue" be. After a chicken-and-egg dance - the bride's family wanted an assurance of the son-in-law's titles while his brother the emperor demanded proof of a bride for the award of the ducal dignity - the time had come. In 1625, Leopold, now elevated to duke, well-fed and forty years old, renounced his ecclesiastical possessions and dignities in order to marry and found a new Tyrolean line of the House of Habsburg with his bride, who was almost 20 years his junior.

The relationship between the prince and the Italian woman was to characterise Innsbruck. The Medici had made a fortune from the cotton and textile trade, but above all from financial transactions, and had risen to political power. Under the Medici, Florence had become the cultural and financial centre of Europe, comparable to the New York of the 20th century or the Arab Emirates of the 21st century. The Florentine cathedral, which was commissioned by the powerful wool merchants' guild, was the most spectacular building in the world in terms of its design and size. Galileo Galilei was the first mathematician of Duke Cosimo II. In 1570, Cosimo de Medici was appointed the first Grand Duke of Tuscany by the Pope. Thanks to generous loans and donations, the Tuscan moneyed aristocracy became European aristocracy. In the 17th century, the city on the Arno had lost some of its political clout, but in cultural terms Florence was still the benchmark. Leopold did everything in his power to catapult his royal seat into this league.

In February 1622, the wedding celebrations between Emperor Ferdinand II and Eleanor of Mantua took place in Innsbruck. Innsbruck was easier to reach than Vienna for the bridal party from northern Italy. Tyrol was also denominationally united and had been spared the first years of the Thirty Years' War. While the imperial wedding was completed in five days, Leopold and Claudia's party lasted over two weeks. The official wedding took place in Florence Cathedral without the presence of the groom. The subsequent celebration in honour of the union of Habsburg and Medici went down as one of the most magnificent in Innsbruck's history and kept the city in suspense for a fortnight. After a frosty entry from the snow-covered Brenner Pass, Innsbruck welcomed its new princess and her family. The husband and his subjects had prayed in advance for divine blessing to purify themselves. Like the Emperor before them, the bridal couple entered the city in a long procession through two specially erected gates. 1500 marksmen fired volleys from all guns. Drummers, pipers and the bells of the Hofkirche accompanied the procession of 750 people as they marvelled at the crowd. A broad entertainment programme with hunts, theatre, dances, music and all kinds of exotic events such as "Bears, Türggen and Moors" left guests and townspeople in raptures and amazement. From today's perspective, a less glamorous highlight was the Cat racein which several riders attempted to chop off the head of a cat hanging by its legs as it rode past.

Leopold's early years in power were less glorious for his subjects. His politics were characterised by many disputes with the estates. As a hardliner of the Counter-Reformation, he was a supporter of the imperial troops. The Lower Engadine, over which Leopold had jurisdiction, was a constant centre of unrest. Under the pretext of protecting the Catholic subjects living there from Protestant attacks, Leopold had the area occupied. Although he was always able to successfully suppress uprisings, the resources required to do so infuriated the population and the estates. The situation on the northern border with Bavaria was also unsettled and required Leopold as warlord. Duke Bernhard of Weimar had taken Füssen and was at the Ehrenberger Klause on the border. Although Innsbruck was spared direct hostilities, it was still part of the Thirty Years' War thanks to the nearby front lines.

He provided the financial means for this through a comprehensive tax reform to the detriment of the middle class. The inflation that was common during wars due to the stagnation of trade, which was important for Innsbruck, worsened the lives of the subjects. In 1622, a bad harvest due to bad weather exacerbated the situation, which was already strained by the interest burden on the state budget caused by old debts. His insistence on enforcing modern Roman law across the board as opposed to traditional customary law did not win him any favour with many of his subjects.

All this did not stop Leopold and Claudia from holding court in a splendid absolutist manner. Innsbruck was extensively remodelled in Baroque style during Leopold's reign. Parties were held at court in the presence of the European aristocracy. Shows such as lion fights with the exotic animals from the prince's own stock, which Ferdinand II had established in the Court Garden, theatre and concerts served to entertain court society.

The morals and customs of the rugged Alpine people were to improve. It was a balancing act between festivities at court and the ban on carnival celebrations for normal citizens. The wrath of God, which after all had brought plague and war, was to be kept away as far as possible through virtuous behaviour. Swearing, shouting and the use of firearms in the streets were banned. The pious court took strict action against pimping, prostitution, adultery and moral decay. Jews also had hard times under Leopold and Claudia. The hatred of the always unloved Hebrew gave rise to one of the most unsavoury traditions of Tyrolean piety. In 1642, Dr Hippolyt Guarinoni, a monastery doctor of Italian origin from Hall and founder of the Karlskirche church in Volders, wrote the legend of the Martyr's child Anderle von Rinn. Inspired by Simon of Trento, who was allegedly murdered by Jews in his home town in 1475, Guarinoni wrote the Anderl song in verse. In Rinn near Innsbruck, an anti-Semitic Anderl cult developed around the remains of Andreas Oxner, who was allegedly murdered by Jews in 1462 - the year had appeared to the doctor in a dream - and was only banned by the Bishop of Innsbruck in 1989.

Innsbruck was not only cleaned morally, but also actually. Waste, which was a particular problem when there was no rain and no water flowing through the sewer system, was regularly cleaned up by princely decree. Farm animals were no longer allowed to roam freely within the city walls. The wave of plague a few years earlier was still fresh in the memory. Bad odours and miasmas were to be kept away at all costs.

After the early death of Leopold, Claudia ruled the country in place of her underage son with the help of her court chancellor Wilhelm Biener (1590 - 1651) with modern, confessionally motivated, early absolutist policies and a strict hand. She was able to rely on a well-functioning administration. The young widow surrounded herself with Italians and Italian-speaking Tyroleans, who brought fresh ideas into the country, but at the same time also toughness in the fight against the Lutheranism showed. In order to avoid fires, in 1636, the Lion house and the Ansitz Ruhelust Ferdinand II, stables and other wooden buildings within the city walls had to be demolished. Silkworm breeding in Trentino and the first tentative plans for a Tyrolean university flourished under Claudia's reign. Chancellor Biener centralised parts of the administration. Above all, the fragmented legal system within the Tyrolean territories was to be replaced by a universal code. To achieve this, the often arbitrary actions of the local petty nobility had to be further disempowered in favour of the sovereign.

This system was not only intended to finance the expensive court, but also the defence of the country. It was not only Protestant troops from southern Germany that threatened the Habsburg possessions. France, actually a Catholic power, also wanted to hold the lands of the Casa de Austria in Spain, Italy and the Vorlanden, today's Benelux countries, harmless. Innsbruck became one of the centres of the Habsburg war council. On the edge of the front in the German lands and centred between Vienna and Tuscany, the city was perfect for Austrians, Spaniards and Italians to meet. The Swedes, notorious for their brutality, threatened Tyrol directly, but were prevented from invading. The castle and ramparts that protected Tyrol were built by unwanted inhabitants of the country, beggars, gypsies and deserted soldiers using forced labour. Defences were built near Scharnitz on today's German border and named after the provincial princess Porta Claudia called.

When Claudia de Medici died in 1648, there was an uprising of the estates against the central government, as there was in England under Cromwell at almost the same time. Claudia, who had never learnt the local German language and was still unfamiliar with local customs even after more than 20 years, had never been particularly popular with the population. However, there was no question of deposing her. The cup of hemlock was passed on to her chancellor. The uncomfortable Biener was recognised by Claudia's successor, Archduke Ferdinand Karl, and the estates as a Persona non grata was imprisoned and, like Charles I, beheaded two years after a show trial in 1651.

A touch of Florence and Medici still characterises Innsbruck today: both the Jesuit church, where Claudia and Leopold found their final resting place, and the Mariahilf parish church still bear the coat of arms of their family with the red balls and lilies. The Old Town Hall in the old town centre is also known as Claudiana known. Remains of the Porta Claudia near Scharnitz still stand today. The theatre in Innsbruck is particularly associated with Leopold's name. The Leopold Fountain in front of the House of Music commemorates him. Those who dare to climb the striking Serles mountain start the hike at the Maria Waldrast monastery, which Leopold devotedly founded in 1621 as a theatre. marvellous picture of our dear lady at the Waldrast to the Servite Order and had Claudia extended. A street name in Saggen was dedicated to Chancellor Wilhelm Biener.

Theatres, country stages, cinemas & Kuno

The Tyrolean State Theatre opposite the Hofburg with its neoclassical façade is still the city's most striking monument to bourgeois, urban evening entertainment. Since its inception, however, this theatre of high culture has largely eked out a dreary existence in terms of audience numbers. From baroque plays about the Passion of Christ in the 16th century to daring productions that were often met with little applause from the audience almost 500 years later, the goings-on at the Landestheater were always the hobbyhorse of a small elite. The majority of Innsbruck's inhabitants passed the time with profane amusements.

Showmen and travelling folk have always been welcome guests in cities. Just like today, there was strict censorship of public performances in the past. What today are age restrictions on cinema films, in the past were restrictions on performances that were not pleasing to God and even complete bans on theatre and drama under particularly pious sovereigns. However, with increasing bourgeoisie and more enlightened moral concepts, the rules gradually became more relaxed.

The Pradler BauerntheaterThe first venue was an open-air stage in the Höttinger Au and, in addition to farmers, craftsmen and students were also part of the ensemble, but this should not detract from the honour of its name and origins. While the state theatre often played to half-empty seats, the amateur actors enjoyed great popularity with their comedies. Employees and labourers made the pilgrimage from the city to the venues in the surrounding villages at the weekend or enjoyed the evening entertainment in pubs. The so-called knight plays with kidnapped princesses, heroic saviours and clumsy villains were particularly popular. Unlike the serious plays in bourgeois theatres, the actors in the peasant theatres interacted with the audience. Interjections from the audience were not stopped, but spontaneously incorporated into the play. It could even happen that the audience, who were not always sober, intervened in the action with their hands.

With increasing success, the company gradually began to professionalise. In 1870, the Pradler Bauerntheater in a hay barn converted into a stage at the Lodronischen Hof in the Egerdachstraße. In the time before the triumph of television, Innsbruck had a whole series of theatres and pubs that entertained their audiences with plays and music. In 1892, the Löwenhaus theatre opened on Rennweg, where the Tyrolean regional studio of the ORF is located today. The wooden building burnt down in the late 1950s, just in time for the rise of state broadcasting. In 1898, the Pradler were guest performers at the Ronacher in Vienna. A few years later, the young and ambitious Ferdinand Exl (1875 - 1942) broke new ground with part of the troupe. For a long time, the saying went: „If you want to go to a farmer's theatre, you won't get your money's worth in the theatre, and if you're not just looking for entertainment in the theatre, but literary stimulation, you won't go to a farmer's theatre." Exl recognised the trend of the time. Employees and workers could not afford the horrendous ticket prices of the state theatre and did not want to see Wagner operas or plays like The Sorrows of Young Werther However, a certain quality of content and presentation was expected. With the so-called literary folk plays by renowned local authors such as Ludwig Anzengruber, Franz Kranewitter and Karl Schönherr, Exl combined entertainment and quality. Anzengruber summarised the development:

„Anzengruber's Tyroleans not only sing Schnaderhüpfel, platteln d'Schuh, swear like Croats and scuffle, but they are also people with a subtle psyche who have their own thoughts about various problems and develop their own philosophy.“

The first play staged by Exl The priest of Kirchfeld from the pen of Anzengruber was published in 1902 in the Österreichischen Hof on the stage in Wilten. The troupe consisted mainly of members of the Exl and Auer families. In 1903, the company known as Exl stage well-known theatre company Adambräu in Adamgasse, from 1904 to 1915 played popular hits such as Kranewitter's pieces Michael Gaismair und Andre Hofer im Lion house at the Hofgarten. In addition to the plays, tourists were also treated to typical local entertainment such as zither recitals and "genuine, smart Tyrolean Schuhplattler dance" was offered. The first international tour to Switzerland and Germany began in 1904. The press and audiences were enthusiastic about the German-national flavoured pieces performed by pithy Tyrolean lads and pretty girls. In 1910, Exl bid farewell to its existence as an amateur troupe and, in addition to a few veterans, mainly hired "Townspeople" and professional actors.

However, the First World War and the associated travel restrictions put the brakes on further tours. The troupe became part of the Innsbruck City Theatrewhose audience was also receptive to lighter fare during the hard times. Ernst Nepo, an artist who was characterised by his Germanism and early membership of the NSDAP, was responsible for the stage sets.

After the toughest post-war years, things started to look up again. From 1924, the Exl stage In addition to the Stadttheater, Exl also regularly performed at the Raimundtheater and the Wiener Komödienhaus in winter. The political developments of the 1930s greatly favoured the German folk spirit that was inherent in many of the plays that Exl brought to the stage. Like Nepo, he also joined the NSDAP, which was banned in Austria, in 1933. A year later, he planned his first tour of the German Reich. The Austrian government, led by Dollfuß, banned the performances in a last stand against the National Socialists. It was not until 1935 that the Exl Bühne in Berlin was able to stage Karl Schönherr's play Faith and home perform. The Berliner Morgenpost of 4 April 1935 described the piece as "...Art that flows from the depths of the German nation and flows back into the hearts of moved and grateful listeners". After 1938, Exl also received media support in Vienna and became known as "...the antithesis of the completely Judaised, artistically Bolshevised... theatre business" was celebrated. The founder of Exl Bühne died in 1942. His wife and son took over the business and became part of the Tyrolean State Theatre after the war. In the 1950s, the theatre group once again toured successfully in West and East Germany before disbanding in 1956.

Times had changed, Cinema killed the Theatre Star. Moving pictures in cinemas were competing with the stage. The enterprising Ferdinand Exl had also foreseen this development early on. In 1912, his ensemble appeared in the French film Speckbacher which heroically portrayed the Tyrolean uprising. The first cinema film flickered across the screen in the Stadtsaal in Innsbruck in 1896, just one year after the world's first ever cinema, in front of a fascinated audience. The cinema quickly became part of everyday life for many people. In addition to silent films, audiences were shown propaganda messages, especially during the war. Cinemas sprang up like mushrooms in the following decades. In 1909, a cinema opened at Maria-Theresien-Straße 10, which was later known as the Central moved to Maria-Theresien-Straße 37. After the war, it became the Nonstop cinemawhere you paid your ticket for a run of news, cartoons, adverts and feature films that was constantly repeated. In 1928, the Red Cross opened the Kammer Lichtspiele in Wilhelm-Greilstraße to finance the new clubhouse. The Triumph was located at Maria-Theresien-Straße 17 and remained a central cinema until the 1990s. Dreiheiligen was home to the Forum cinema, which is now the Z6 youth centre. In 1933, the Höttinger Gasse opened the Lion cinemawhich was built in 1959 as the Metropol in the listed Malfatti house opposite the Inn bridge, where it still exists today. In the final phase of the Second World War, the Laurin light shows Innsbruck's largest cinema in the middle of the South Tyrolean settlement in Gumppstraße opened its doors. Robert and Walter Kinigadner, two South Tyrolean optants who had already gained experience in the cinema industry in Brixen, took over the running of the 800-seat cinema. Harmless local films alternated with Nazi propaganda. The Exl stage used the Laurin, which functioned as a cinema until the 1970s, for theatre performances. Today, a supermarket is located behind the pillars at the formerly grand entrance. On the wall above the cash desk area, you can still see the murals depicting the legend of the legendary dwarf king Laurin and the German hero Dietrich von Bern in the typical look of National Socialist art. In 1958, on the premises of the former Innsbruck Catholic Workers' Association, the Leocinemawhich is still in operation today and is an integral part of the Innsbruck film scene.

For a short time, cinema and theatre coexisted before cinema took the upper hand. At its peak in 1958, Innsbruck's cinemas sold an incredible 3.5 million tickets. Then the television in the living room gradually took over information and evening entertainment. In addition to entertainment, the cinema also took on a role in sexual education. In the 1970s, naked breasts flickered across the screens for the first time. Films such as Schulmädchenreport and Josefine Mutzenbacher also brought the sexual revolution a little closer to the Tyroleans.

When the Austrian Broadcasting When the new radio went on air in 1955, hardly anyone had a terminal to receive the meagre programme. That was soon to change. In Innsbruck, the Metropol at the Inn bridge and the new bridge built at the turn of the millennium Cineplexx There are still two big players in Wilten. Cinematograph und Leocinema are aimed at an alternative audience away from the blockbusters. The open-air cinema takes place in the Zeughaus in August. The Pradl theatre troupe has survived to this day, albeit under a new name. In 1958, they found a new home in the Bierstindl cultural pub. The amateur theatre troupe Innsbruck Knights' Games enjoys great popularity and full ranks to this day. The play The rogue Kuno von Drachenfels revives the tradition of past centuries every year, including a repeat of the beheading scene and humorous interaction with the audience. A street in the Höttinger Au neighbourhood commemorates Ferdinand Exl. The Alpenheim country house in Saggen, better known today as Villa Exl, where the family lived, is a Tyrolean Heimatstil building with paintings by Raphael Thaler that is well worth seeing.

Romance, sunless summers and apology cards

Thanks to the university, its professors and the young people it attracted and produced, Innsbruck also sniffed the morning air of the Enlightenment in the 18th century in the era of Maria Theresa, even if the Jesuit faculty leadership put the brakes on it. 1741 saw the founding of the Societas Academica Litteraria a circle of scholars in the Taxispalais. The masonic lodge was founded in 1777 To the three mountains, four years later, the Tyrolean Society for Arts and Science was founded. The spirit of reason in the time of Maria Theresa and Emperor Joseph also found its way into Innsbruck's elite. Spurred on by the French Revolution, some students even declared their allegiance to the Jacobins. Under Emperor Franz, all these associations were banned and strictly monitored after the declaration of war on France in 1794. Enlightenment ideas were frowned upon by large sections of the population even before the French Revolution. At the latest after the beheading of Marie Antoinette, the Emperor's sister, and the outbreak of war between the French Republic and the monarchies of Europe, they were considered dangerous. Who wanted to be considered a Jacobin when it came to defending their homeland?

After the Napoleonic Wars, Innsbruck was slow to recover, both economically and mentally. Adalbert Stifter (1805 -1868), probably the most famous writer of Austrian Romanticism, described Innsbruck in the 1830s in his travelogue Tyrol and Vorarlberg as follows:

„The inns were bad, the pavements wretched, long gutters overhung the narrow streets, which were bordered on both sides by dull arches... the beautiful banks of the Inn were unpaved, but covered with heaps of rubbish and criss-crossed by cesspools.“

Die kleine Stadt am Rande des Kaiserreiches hatte etwas mehr als 12.000 Einwohner, „ohne die Soldaten, Studenten und Fremden zu rechnen“. University, grammar school, Reading casino, music club, theatre and museum were evidence of a developing, modern urban culture. There was a Deutsches Kaffeehaus, a Restoration in the courtyard garden and several traditional inns such as the White cross, the Österreichischen Hofwhich Grape, das Katzung, das Mouthingeach of which Goldenen Adler, Stern und Hirsch. After 1830, the open sewers were blocked and made more hygienic, roads were repaired and bridges renovated. The overdue straightening and taming of the Inn and Sill rivers, which had begun before the turmoil of war, was also tackled. The biggest innovation for the population came in 1830, when oil lamps lit up the town at night. It was probably just a dim twilight created by the more than 150 lamps mounted on pillars and arm chandeliers, but for contemporaries it was a true revolution.

Die bayerische Besatzung war verschwunden, die Ideen der Denker der Aufklärung und der Französischen Revolution hatten sich aber in einigen Köpfen des städtischen Milieus verfangen. Natürlich waren es keine atheistischen, sozialistischen oder gar umstürzlerischen Gedanken, die sich breit machten. Es ging vor allem um wirtschaftliche, politische und gesellschaftliche Teilhabe des Bürgertums. Das Vereinswesen feierte eine Renaissance. Was heute wenig spektakulär klingt, war zur Regierungszeit Metternichs aufsehenerregend. Zwischen dem Beginn der Napoleonischen Kriege mit dem revolutionären Frankreich 1797 und dem Wiener Kongress waren Vereine allgemein verboten gewesen. Wer auf sich hielt, trat nun einer dieser neuartigen Gesellschaften bei. "Innsbruck has a music society, an agricultural society and a mining and geological society." stand etwa im Reiseführer Beda Webers wie ein Qualitätssiegel für die Stadt zu lesen. Es galt das tugendhafte Miteinander zum Wohl der weniger Begüterten und die Erziehung der Massen mit dem Treiben in den Vereinen zu forcieren. Wissenschaft, Literatur, Theater und Musik, aber auch Initiativen wie der Innsbruck Beautification Association, but also practical institutions such as the voluntary fire brigade established themselves as pillars of a previously unknown civil society. One of the first associations to be formed was the Innsbruck Music Society, from which the Tyrolean State Conservatory emerged. In keeping with the spirit of the times, men and women were not members of the same organisations. Women were mainly involved in charitable organisations such as the Women's association for the promotion of infant care centres and female industrial schools. Female participation in the political discourse was not desired.

In addition to Christian charity, a thirst for recognition and prestige were probably also major incentives for members to get involved in the clubs. People met to see and be seen. Good deeds, demonstrating education and leading a virtuous life were then, as now, the best PR for oneself.

Club life also served as entertainment on long evenings without electric light, television and the internet. Students, civil servants, members of the lower nobility and academics met in the pubs and coffee houses to exchange ideas. This was not only about highly intellectual and abstract matters, but also about profane realpolitik such as the suspension of internal tariffs, which made people's lives unnecessarily expensive. Culturally, the bourgeois educated elite in the Romantic and Biedermeier periods discovered the cultural escape into an intact past for themselves. After decades of political confusion, war and hardship, people wanted a distraction from the recent past, just as they did after 1945. Antiquity and its thinkers celebrated a second renaissance in Innsbruck, as in the rest of Europe. Romantic thinkers of the 18th and early 19th centuries such as Winckelmann, Lessing and Hegel were influential. The Greeks were „Noble simplicity and quiet greatness" attested. Goethe wanted the "Search the land of the Greeks with your soul" and travelled to Italy in search of his longing for the good, pre-Christian times in which the people of the Golden Age cultivated an informal relationship with their gods. Roman Stoic virtues were transported into the modern age as role models and formed the basis for bourgeois frugality and patriotism, which became very fashionable. Philologists combed through the texts of ancient writers and philosophers and conveyed a pleasing "Best of" into the 19th century. Columns, sphinxes, busts and statues with classical proportions adorned palaces, administrative buildings and museums such as the Ferdinandeum. Students and intellectuals such as the Briton Lord Byron were so inspired by the Panhellenism and the idea of nationalism that they risked their lives in the Greek struggle for independence against the Ottoman Empire. After the end of the Holy Roman Empire, Pan-Germanism became the political fashion of the liberal bourgeoisie in Innsbruck.

Kanzler Clemens von Metternichs (1773 – 1859) Polizeistaat hielt diese gesellschaftlichen Regungen lange Zeit unter Kontrolle. Zeitungen, Flugblätter, Schriften mussten sich an die Vorgaben der strengen Zensur anpassen oder im Untergrund verbreitet werden. Autoren wie Hermann von Gilm (1812 – 1864) und Johann Senn (1792 – 1857), an beide erinnern heute Straßen in Innsbruck, verbreiteten in Tirol anonym politisch motivierte Literatur. Der vielleicht bekannteste Public Intellectual des Vormärz war wahrscheinlich Adolf Pichler (1819 – 1900), dem bereits kurz nach seinem Ableben unter gänzlich anderen Vorzeichen in der Stadtpolitik der späten Monarchie ein Denkmal gewidmet wurde und nach dem heute das Bundesrealgymnasium am gleichnamigen Platz gewidmet ist. Bücher und Vereine standen unter Generalverdacht. Der Innsbrucker Musikverein lehrte im Rahmen seiner Ausbildung auch die Deklamation, das Vortragen von Texten, Musik und Reden, die Inhalte wurden von der Obrigkeit streng überwacht. Alle Arten von Vereinen wie die Innsbrucker Liedertafel and student fraternities, even the members of the Ferdinandeum were spied on. The social movements forming in the working-class neighbourhoods were particularly targeted by Metternich's secret police. Despite their demonstrative loyalty to the emperor, the marksmen were also on the list of institutions to be observed. They were considered too rebellious, not only towards foreign powers, but also towards the Viennese central government. The mix of Greater German nationalist ideas and Tyrolean patriotism presented with the pathos of Romanticism seems strangely harmless today, but was neither comfortable nor acceptable to the Metternich state apparatus.

However, political activism was a marginal phenomenon that only occupied a small elite. After the mines and salt works had lost their profitability in the 17th century and transit lost its economic importance due to the new trade routes across the Atlantic, Tyrol had become a poor region. The Napoleonic Wars had raged for over 20 years. The year 1809 went down as Tyrolean heroic age in the historiography of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the consequences of heroism were barely highlighted. Although the Austrian Empire was one of the victorious powers after the Congress of Vienna, its economic situation was miserable. As after the world wars of the 20th century, many men had not returned home during the coalition wars. The university, which drew young aristocrats into the city's economic cycle, was not reopened until 1826. Unlike industrial locations in Bohemia, Moravia, Prussia or England, the hard-to-reach city in the Alps was only just beginning to develop into a modern labour market. Tourism was also still in its infancy and was not a Cash Cow. It is no wonder that hardly any buildings in the Biedermeier style have survived in Innsbruck. And then there was a volcano on the other side of the world that had an undue influence on the fate of the city of Innsbruck. In 1815, Tambora erupted in Indonesia and sent a huge cloud of dust, sulphur and ash around the world. In 1816 Year without summer into history. All over Europe, there were freak weather conditions, floods and failed harvests. The Alps, an already difficult part of the world to farm, were not exempt from this.

The economic upheavals and price increases led to hardship and misery, especially among the poorer sections of the population. In the 19th century, caring for the poor was a task for the communities, usually with the support of wealthy citizens as patrons with the idea of Christian charity. The state, the community, the church and the newly emerging civil society in the form of associations began to look after the welfare of the poorest sections of the population. Charity concerts, collections and appeals for donations were organised. The measures often contained an enlightened component, even if the means to an end seem strange and alien today. In Innsbruck, for example, a begging ordinance came into force that banned dispossessed people from marrying. Almost 1000 citizens were categorised as alms recipients and beggars.

As the need grew and the city coffers became emptier, Innsbruck came up with an innovation that was to last for over 100 years: The New Year's apology card. Even back then, it was customary to visit relatives on the first day of the year to give each other a Happy New Year to make a wish. It was also customary for needy families and beggars to knock on the doors of wealthy citizens to ask for alms at New Year. The introduction of the New Year's relief card killed several birds with one stone. The buyers of the card were able to institutionalise and support their poorer members in a regulated way, similar to the way street newspapers are bought today. Twenty is possible. At the same time, the New Year's apology card served as a way of avoiding the unpopular obligatory visits to relatives. Those who hung the card on their front door also signalled to those in need that no further requests for alms were necessary, as they had already paid their contribution. Last but not least, the noble donors were also favourably mentioned in the media so that everyone could see how much they cared for their less fortunate fellow human beings in the name of charity.

The New Year's apology cards were a complete success. At their premiere at the turn of the year from 1819 to 1820, 600 were sold. Many communities adopted the Innsbruck recipe. In the magazine "The Imperial and Royal Privileged Bothe of and for Tyrol and Vorarlberg", the proceeds for Bruneck, Bozen, Trient, Rovereto, Schwaz, Imst, Bregenz and Innsbruck were published on 12 February. Other institutions such as fire brigades and associations also adopted the well-functioning custom to raise funds for their cause. The construction of the new Höttinger parish church was financed to a large extent from the proceeds of specially issued apology cards in addition to donations. The varied designs ranged from Christian motifs to portraits of well-known personalities, official buildings, new buildings, sights and curiosities. Many of the designs can still be seen in the Innsbruck City Archives.

The master builders Gumpp and the baroqueisation of Innsbruck

The works of the Gumpp family still strongly characterise the appearance of Innsbruck today. The baroque parts of the city in particular can be traced back to them. The founder of the dynasty in Tyrol, Christoph Gumpp (1600-1672), was actually a carpenter. However, his talent had chosen him for higher honours. The profession of architect or artist did not yet exist at that time; even Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci were considered craftsmen. After working on the Holy Trinity Church, the Swabian-born Gumpp followed in the footsteps of the Italian master builders who had set the tone under Ferdinand II. At the behest of Leopold V, Gumpp travelled to Italy to study theatre buildings and to learn from his contemporary style-setting colleagues his expertise for the planned royal palace. Comedihaus polish up.

His official work as court architect began in 1633. New times called for a new design, away from the Gothic-influenced architecture of the Middle Ages and the horrors of the Thirty Years' War. Over the following decades, Innsbruck underwent a complete renovation under the regency of Claudia de Medici. Gumpp passed on his title to the next two generations within the family. The Gumpps were not only active as master builders. They were also carpenters, painters, engravers and architects, which allowed them to create a wide range of works similar to the Tiroler Moderne around Franz Baumann and Clemens Holzmeister at the beginning of the 20th century to realise projects holistically. They were also involved as planners in the construction of the fortifications for national defence during the Thirty Years' War.

Christoph Gumpp's masterpiece, however, was the construction of the Comedihaus in the former ballroom. The oversized dimensions of the then trend-setting theatre, which was one of the first of its kind in Europe, not only allowed plays to be performed, but also water games with real ships and elaborate horse ballet performances. The Comedihaus was a total work of art in and of itself, which in its significance at the time can be compared to the festival theatre in Bayreuth in the 19th century or the Elbphilharmonie today.

His descendants Johann Martin Gumpp the Elder, Georg Anton Gumpp and Johann Martin Gumpp the Younger were responsible for many of the buildings that still characterise the townscape today. The Wilten collegiate church, the Mariahilfkirche, the Johanneskirche and the Spitalskirche were all designed by the Gumpps. In addition to designing churches and their work as court architects, they also made a name for themselves as planners of secular buildings. Many of Innsbruck's town houses and city palaces, such as the Taxispalais or the Altes Landhaus in Maria-Theresien-Straße, were designed by them. With the loss of the city's status as a royal seat, the magnificent large-scale commissions declined and with them the fame of the Gumpp family. Their former home is now home to the Munding confectionery in the historic city centre. In the Pradl district, Gumppstraße commemorates the Innsbruck dynasty of master builders.

Baroque: art movement and art of living

Anyone travelling in Austria will be familiar with the domes and onion domes of churches in villages and towns. This form of church tower originated during the Counter-Reformation and is a typical feature of the Baroque architectural style. They are also predominant in Innsbruck's cityscape. Innsbruck's most famous places of worship, such as the cathedral, St John's Church and the Jesuit Church, are in the Baroque style. Places of worship were meant to be magnificent and splendid, a symbol of the victory of true faith. Religiousness was reflected in art and culture: grand drama, pathos, suffering, splendour and glory combined to create the Baroque style, which had a lasting impact on the entire Catholic-oriented sphere of influence of the Habsburgs and their allies between Spain and Hungary.

The cityscape of Innsbruck changed enormously. The Gumpps and Johann Georg Fischer as master builders as well as Franz Altmutter's paintings have had a lasting impact on Innsbruck to this day. The Old Country House in the historic city centre, the New Country House in Maria-Theresien-Straße, the countless palazzi, paintings, figures - the Baroque was the style-defining element of the House of Habsburg in the 17th and 18th centuries and became an integral part of everyday life. The bourgeoisie did not want to be inferior to the nobles and princes and had their private houses built in the Baroque style. Pictures of saints, depictions of the Mother of God and the heart of Jesus adorned farmhouses.

Baroque was not just an architectural style, it was an attitude to life that began after the end of the Thirty Years' War. The Turkish threat from the east, which culminated in the two sieges of Vienna, determined the foreign policy of the empire, while the Reformation dominated domestic politics. Baroque culture was a central element of Catholicism and its political representation in public, the counter-model to Calvin's and Luther's brittle and austere approach to life. Holidays with a Christian background were introduced to brighten up people's everyday lives. Architecture, music and painting were rich, opulent and lavish. In theatres such as the Comedihaus dramas with a religious background were performed in Innsbruck. Stations of the cross with chapels and depictions of the crucified Jesus dotted the landscape. Popular piety in the form of pilgrimages and the veneration of the Virgin Mary and saints found its way into everyday church life. Multiple crises characterised people's everyday lives. In addition to war and famine, the plague broke out particularly frequently in the 17th century. The Baroque piety was also used to educate the subjects. Even though the sale of indulgences was no longer a common practice in the Catholic Church after the 16th century, there was still a lively concept of heaven and hell. Through a virtuous life, i.e. a life in accordance with Catholic values and good behaviour as a subject towards the divine order, one could come a big step closer to paradise. The so-called Christian edification literature was popular among the population after the school reformation of the 18th century and showed how life should be lived. The suffering of the crucified Christ for humanity was seen as a symbol of the hardship of the subjects on earth within the feudal system. People used votive images to ask for help in difficult times or to thank the Mother of God for dangers and illnesses they had overcome.

The historian Ernst Hanisch described the Baroque and the influence it had on the Austrian way of life as follows:

„Österreich entstand in seiner modernen Form als Kreuzzugsimperialismus gegen die Türken und im Inneren gegen die Reformatoren. Das brachte Bürokratie und Militär, im Äußeren aber Multiethnien. Staat und Kirche probierten den intimen Lebensbereich der Bürger zu kontrollieren. Jeder musste sich durch den Beichtstuhl reformieren, die Sexualität wurde eingeschränkt, die normengerechte Sexualität wurden erzwungen. Menschen wurden systematisch zum Heucheln angeleitet.“

The rituals and submissive behaviour towards the authorities left their mark on everyday culture, which still distinguishes Catholic countries such as Austria and Italy from Protestant regions such as Germany, England or Scandinavia. The Austrians' passion for academic titles has its origins in the Baroque hierarchies. The expression Baroque prince describes a particularly patriarchal and patronising politician who knows how to charm his audience with grand gestures. While political objectivity is valued in Germany, the style of Austrian politicians is theatrical, in keeping with the Austrian bon mot of "Schaumamal".

Innsbruck and National Socialism

In the 1920s and 30s, the NSDAP also grew and prospered in Tyrol. The first local branch of the NSDAP in Innsbruck was founded in 1923. With "Der Nationalsozialist - Combat Gazette for Tyrol and Vorarlberg“ published its own weekly newspaper. In 1933, the NSDAP also experienced a meteoric rise in Innsbruck with the tailwind from Germany. The general dissatisfaction and disenchantment with politics among the citizens and theatrically staged torchlight processions through the city, including swastika-shaped bonfires on the Nordkette mountain range during the election campaign, helped the party to make huge gains. Over 1800 Innsbruck residents were members of the SA, which had its headquarters at Bürgerstraße 10. While the National Socialists were only able to win 2.8% of the vote in their first municipal council election in 1921, this figure had already risen to 41% by the 1933 elections. Nine mandataries, including the later mayor Egon Denz and the Gauleiter of Tyrol Franz Hofer, were elected to the municipal council. It was not only Hitler's election as Reich Chancellor in Germany, but also campaigns and manifestations in Innsbruck that helped the party, which had been banned in Austria since 1934, to achieve this result. As everywhere else, it was mainly young people in Innsbruck who were enthusiastic about National Socialism. They were attracted by the new, the clearing away of old hierarchies and structures such as the Catholic Church, the upheaval and the unprecedented style. National Socialism was particularly popular among the big German-minded lads of the student fraternities and often also among professors.

When the annexation of Austria to Germany took place in March 1938, civil war-like scenes ensued. Already in the run-up to the invasion, there had been repeated marches and rallies by the National Socialists after the ban on the party had been lifted. Even before Federal Chancellor Schuschnigg gave his last speech to the people before handing over power to the National Socialists with the words "God bless Austria" had closed on 11 March 1938, the National Socialists were already gathering in the city centre to celebrate the invasion of the German troops. The police of the corporative state were partly sympathetic to the riots of the organised manifestations and partly powerless in the face of the goings-on. Although the Landhaus and Maria-Theresien-Straße were cordoned off and secured with machine-gun posts, there was no question of any crackdown by the executive. "One people - one empire - one leader" echoed through the city. The threat of the German military and the deployment of SA troops dispelled the last doubts. More and more of the enthusiastic population joined in. At the Tiroler Landhaus, then still in Maria-Theresienstraße, and at the provisional headquarters of the National Socialists in the Gasthaus Old Innspruggthe swastika flag was hoisted.

On 12 March, the people of Innsbruck gave the German military a frenetic welcome. To ensure hospitality towards the National Socialists, Mayor Egon Denz had each worker paid a week's wages. On 5 April, Adolf Hitler personally visited Innsbruck to be celebrated by the crowd. Archive photos show a euphoric crowd awaiting the Führer, the promise of salvation. Mountain fires in the shape of swastikas were lit on the Nordkette. The referendum on 10 April resulted in a vote of over 99% in favour of Austria's annexation to Germany. After the economic hardship of the interwar period, the economic crisis and the governments under Dollfuß and Schuschnigg, people were tired and wanted change. What kind of change was initially less important than the change itself. "Showing them up there", that was Hitler's promise. The Wehrmacht and industry offered young people a perspective, even those who had little to do with the ideology of National Socialism in and of itself. The fact that there were repeated outbreaks of violence was not unusual for the interwar period in Austria anyway. Unlike today, democracy was not something that anyone could have got used to in the short period between the monarchy in 1918 and the elimination of parliament under Dollfuß in 1933, which was characterised by political extremes. There is no need to abolish something that does not actually exist in the minds of the population.

Tyrol and Vorarlberg were combined into a Reichsgau with Innsbruck as its capital. Even though National Socialism was viewed sceptically by a large part of the population, there was hardly any organised or even armed resistance, as the Catholic resistance OE5 and the left in Tyrol were not strong enough for this. There were isolated instances of unorganised subversive behaviour by the population, especially in the arch-Catholic rural communities around Innsbruck. The power apparatus dominated people's everyday lives too comprehensively. Many jobs and other comforts of life were tied to an at least outwardly loyal attitude to the party. The majority of the population was spared imprisonment, but the fear of it was omnipresent.

The regime under Hofer and Gestapo chief Werner Hilliges also did a great job of suppression. In Tyrol, the church was the biggest obstacle. During National Socialism, the Catholic Church was systematically combated. Catholic schools were converted, youth organisations and associations were banned, monasteries were closed, religious education was abolished and a church tax was introduced. Particularly stubborn priests such as Otto Neururer were sent to concentration camps. Local politicians such as the later Innsbruck mayors Anton Melzer and Franz Greiter also had to flee or were arrested. It would go beyond the scope of this article to summarise the violence and crimes committed against the Jewish population, the clergy, political suspects, civilians and prisoners of war. The Gestapo headquarters were located at Herrengasse 1, where suspects were severely abused and sometimes beaten to death with fists. In 1941, the Reichenau labour camp was set up in Rossau near the Innsbruck building yard. Suspects of all kinds were kept here for forced labour in shabby barracks. Over 130 people died in this camp consisting of 20 barracks due to illness, the poor conditions, labour accidents or executions. Prisoners were also forced to work at the Messerschmitt factory in the village of Kematen, 10 kilometres from Innsbruck. These included political prisoners, Russian prisoners of war and Jews. The forced labour included, among other things, the construction of the South Tyrolean settlements in the final phase or the tunnels to protect against air raids in the south of Innsbruck. In the Innsbruck clinic, disabled people and those deemed unacceptable by the system, such as homosexuals, were forcibly sterilised.

The memorials to the National Socialist era are few and far between. The Tiroler Landhaus with the Liberation Monument and the building of the Old University are the two most striking memorials. The forecourt of the university and a small column at the southern entrance to the hospital were also designed to commemorate what was probably the darkest chapter in Austria's history.