Philippine-Welser-Straße

Philippine-Welser-Straße

Worth knowing

If you turn into Philippine-Welser-Straße from the west, the large blocks of flats make it hard to believe that this was the original village of Amras. To this day, real Amras locals mockingly call the residents of the modern complexes "Zuagroaste“, „Blöckler" or "Stiegenhäusler". After a few metres, however, you can already see the farmhouses that characterise Amras as a rural village in the city.

The street is named after Philippine Welser, the wife of Ferdinand II, who is still popular with the population today. The princess would have been delighted with the lush gardens in front of the Amras farmhouses, some of which look like small castles. The façades and bay windows are decorated with Catholic motifs in the style of rural Baroque, which are embedded in rural Tyrolean life. The lavishly renovated farmhouses give an idea of how the modern farmers of Amras earned their living less from time-consuming field labour and more from the sale and management of real estate, which was granted to them by the 1848 land relief and has increased in value over the centuries. House numbers 85, 88 and 101 are particularly worth seeing.

Remarkable is the recurring depiction of the "Amraser Gnadenmutter", a local variation on the veneration of the Madonna. According to legend, the Mother of mercy a child who had fallen out of a window. The princely parents then donated an image of the Mother of mercywhich has a special place in the folklore of the region and is a popular motif for the Amras farmhouses. It is an example of legendary figures that combine with Christianity to form a particularly pious mixture. Since 1997, there has been a statue in front of the Stecherhof In the centre of the street is the marble village fountain, which houses a statue of St. Pankraz, the Mother of Mercy and the Innsbruck city coat of arms as a symbol of the incorporation of the municipality of Amras into Innsbruck.

The painting on the façade above the entrance to the Amras parish church by Tyrolean artist Hans Andre shows the Mother of mercy next to a Tyrolean marksman and a woman in traditional Tyrolean costume. The Amras parish church can be seen in the background. The depiction of the church on itself is a special expression of Tyrolean popular piety that can be seen on several places of worship in the region. It is a symbol of the Holy Land Tyrolwhich is based on the covenant with the Sacred Heart of Jesus of 1796.

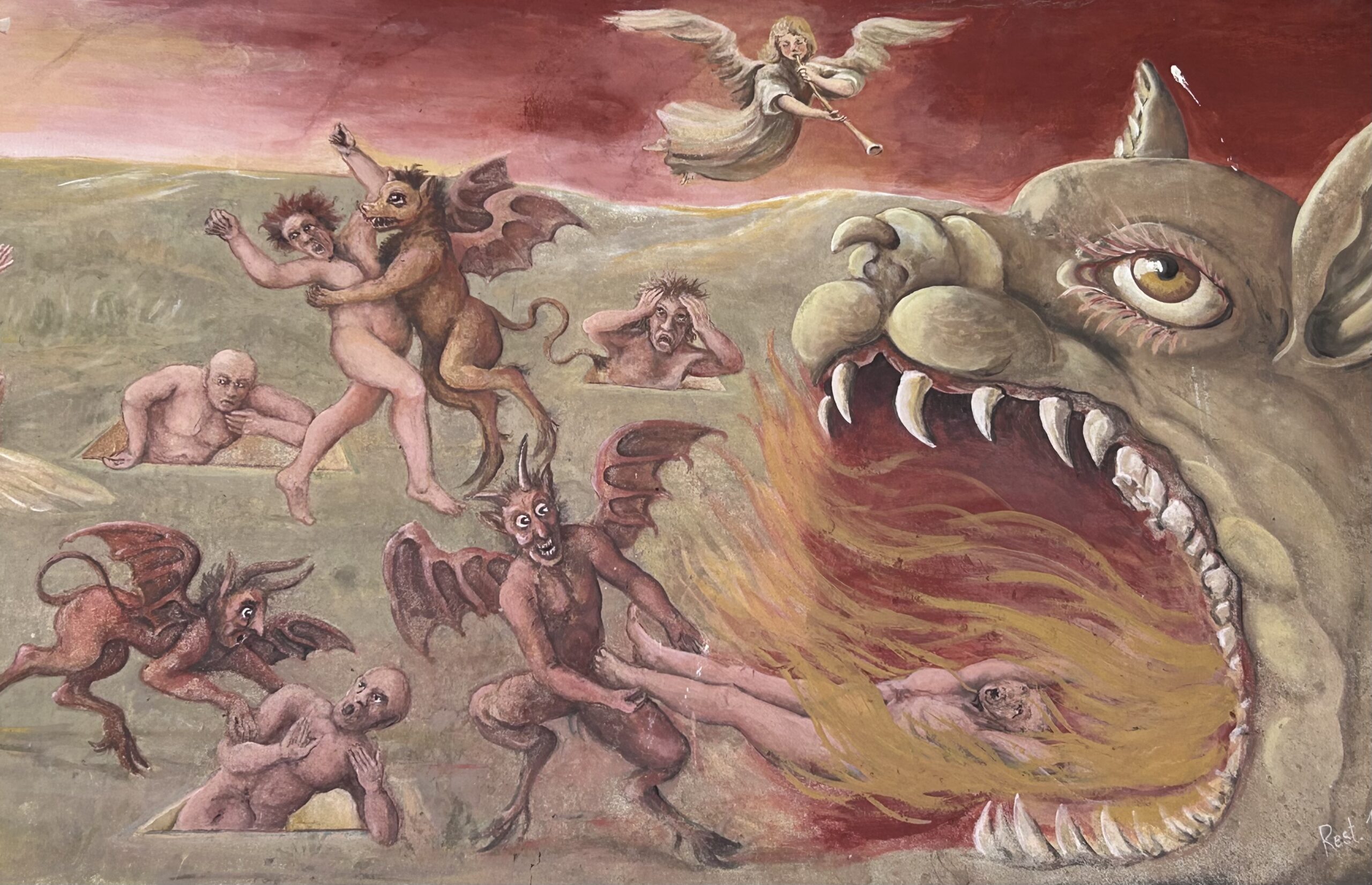

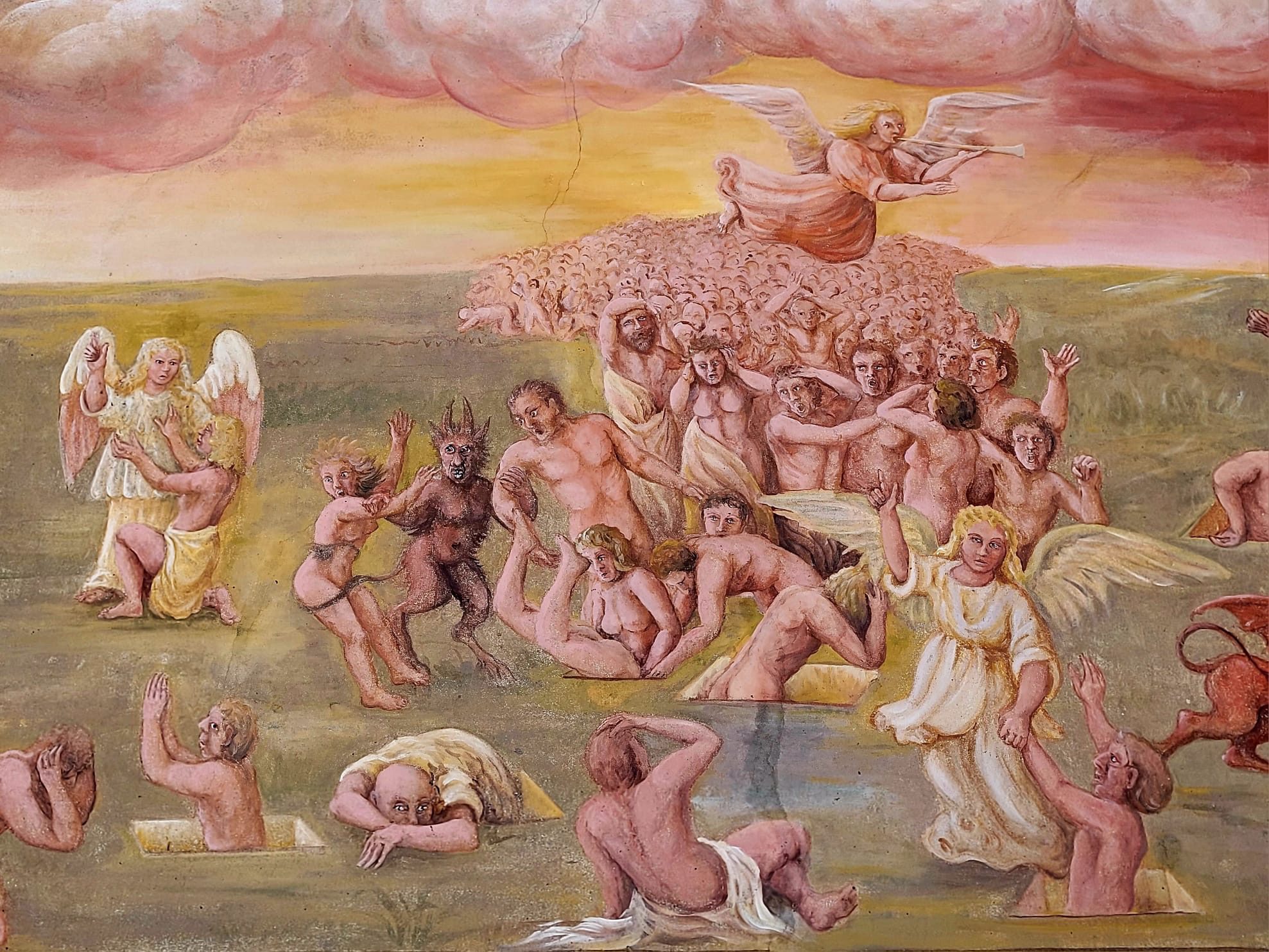

Another painting worth seeing can be found on the church's warrior chapel. The depiction of the Last Judgement with saints, angels and devils leading the good citizens to paradise after their earthly life, while the bad are dragged into the pit of hell, is a wonderful example of the religious imagination of the Baroque Counter-Reformation. The church tower, crowned by a pointed spire, is the highest in the city of Innsbruck.

Tyrol in the hands of farmers

Identification with the farming community is still very high in Tyrol. Although less than 2% of the population live from agriculture today, farmers manage to have above-average representation in society thanks to their lively associations, skilful self-presentation and political structures. This was not always the case. For centuries, the vast majority of people worked in agriculture, but farmers had hardly any political clout. The landlords not only owned the land, but also had power over the people. Builders itself. There was no question of the subjects acting independently as active participants in the economic cycle. Rent was regularly collected in kind. The local petty nobility administered the farming communities within their territory and paid their dues to the sovereign or the bishop. Only gradually did the peasantry develop into the proud status it still enjoys today.

The hierarchical structure of the estate was similar to that of medieval and early modern society as a whole. There were three types of relationship between peasants and landlords. Throughout the Middle Ages, the Leibgeding common. Peasants worked on the manorial estates as serfs. This serfdom could go so far that marriage, property, mobility and other matters of personal life could not be freely decided. This form was already a thing of the past in the vast majority of Tyrol in the early modern period.

The second form, the Free pencilThe tenancy was a lease of a farm for a certain period of time, usually one year. It was usually extended, as both landlords and farmers benefited from a constant business relationship, similar to employers and employees today. However, the subjects did not have a legal right to remain on their estate, nor were there any documents that contractually regulated the legal transaction. Oral contracts were subject to customary law and tradition. The landlord could move his builders back and forth within his estates or hire them out completely. pin...to throw them out the door. If the farm was passed on from a farmer to his son within the family with the consent of the landlord, a Honour due, a payment of up to 10% of the farm value.

The third and most modern form was the Inheritance loan. Even with this form of lease, the land remained the property of the landlord, a Staking was no longer so easily possible. Heirs paid less interest than Pen people. In autumn, either on St Gall's Day (16 October) or on St Martin's Day (11 November), the farmers had to pay their rent in hereditary loans, which shifted more and more from payments in kind to the sounding of coins. Farmers were able to expand their farms through acquisitions or skilful marriage policies. Farms were inherited within the family. Old farmers who sold their property with the warm handThe heirs, who were handed over during their lifetime, retained the right to live at the court and were paid an agreed Ausgedinge supplied.

Peasant inheritance law varied from region to region. In the North Tyrolean Oberland and in South Tyrol, the Real division in other words, the farm was divided up among all the heirs. This automatically led to a fragmentation of the estates and lower profitability. In the Innsbruck region and the lowlands, on the other hand, the Division of inheritance common practice. With few exceptions, the eldest child inherited the entire farm in order to maintain the structure. The siblings of the sole heir usually had no choice but to leave. They had to earn a living as servants, craftsmen, farmhands and maidservants. When Söllhäuslerpeople with a small house and perhaps a garden but no land to speak of, they belonged to the Pofelwhich was made up of innkeepers, travelling folk, prostitutes, servants, maidservants and beggars. In the event of illness or destitution, they had claims against the heir and could be accommodated on the farm for a certain period of time. Depending on the value of the farm, the heir's siblings were also entitled to interest, although this was usually little or nothing. Even back then, farmers were skilful at minimising the book value of their estates.

In the 15th century, the political rules of the game began to change. The lesser nobility had always been a thorn in the side of the sovereign princes as an intermediate level between them and their subjects with their own jurisdiction. Step by step, a modern state began to emerge at the end of the Middle Ages. Monarchs and the high aristocracy wanted to exercise direct rule over their subjects. Although the estate-based society and birthright were not affected by this development, the role of the lesser nobility changed. They went from being lords with power of disposal over their subjects to administrators of their estates and organisers of national defence in the name of the respective prince.

In order to minimise the influence of the lesser nobility, Frederick IV stipulated in his Land Ordinance of 1404 that the legal recognition of the Inheritance loan fixed. With the exception of the territories of the prince-bishops of Trento and Brixen in Tyrol, this form of granting agricultural estates subsequently prevailed over the Free pencil through. Legal disputes between peasants and landlords had to be negotiated before the sovereign. With this daring political act, Frederick bought the immediate affection and loyalty of his subjects in order to gain direct access to military manpower and tax payments. The peasants had the advantage of no longer being at the mercy of their landlords.

With the Inheritance loan farmers became entrepreneurs of sorts, participating in early capitalism as market players. Although they were still subject to the whims of nature and the political climate, such as wars or customs regulations, they now had the opportunity to rise from the subsistence level of previous centuries. After paying the tithe and providing for the household, they sold their goods on the market. Motivated and hard-working farmers were able to build up a certain level of prosperity.

As a result of the economic changes that took place in Innsbruck from the 15th century due to its elevation to a royal seat and in the towns of Hall and Schwaz due to the mining industry, the farmers in the neighbouring villages also benefited from the upswing. The people who worked as officials at court or in the New Industry The people who were employed in mining formed a middle class with greater purchasing power. The demand for meat increased. This in turn led to a change in agriculture. Farmers discovered livestock farming as a more lucrative source of income than arable farming.

Thanks to inflation following the discovery of the New World and the financial upheavals of the 16th century, the amount of rent that farmers had to pay as a monetary value also decreased. Smaller farmers, who received their farms as freeholds and had to pay their dues in kind, suffered from the devaluation of money, while large farms benefited from it.

These developments led to new social relationships on the farms themselves and to greater differences within the peasantry. Peasants presided over their servants in all matters, similar to the Pater Familias of the extended family in ancient Rome. Life on the estates had little to do with the wholesome family life that is often propagated today as a traditional Tyrolean lifestyle. Rather, they were clan-like extended family groups that were under the strict regime of the farmer in everyday life: He determined the working day, food, lodging, meagre leisure time and personal relationships. Clear hierarchies developed in the villages. Hereditary farmers had higher status than Pen farmers. Large farmers had more prestige than small farmers. They often presided over their villages. Particularly successful and loyal farmers were awarded their own family coat of arms by the prince and were honoured as Peasant nobility. At a time when honour and status within society were worth at least as much as hard cash under the pillow, the title of free peasant was more than a mere symbol. These structures persisted in the countryside well into the 19th century, and in more remote regions of the country into the 20th century. At the outbreak of the First World War, more than 50% were still working in agriculture in Tyrol. The beautiful farmhouses in Hötting, Wilten Pradl and Amras, on whose façades the family coats of arms and the reference to their status as Hereditary farm are testimony to the rise of the peasantry in the early modern period.

Philippine Welser: Klein Venedig, Kochbücher und Kräuterkunde

Philippine Welser (1527 - 1580) was the wife of Archduke Ferdinand II and one of Innsbruck's most popular rulers. The Welsers were one of the wealthiest families of their time. Their uncle Bartholomäus Welser was similarly wealthy to Jakob Fugger and also came from the class of merchants and financiers who had acquired enormous wealth around 1500. The pillars of this wealth were the spice trade with India and the mining and metal trade with the American colonies. Welser had also granted loans to the Habsburgs. Instead of paying off the loans, Emperor Charles V pledged some of the newly annexed lands in America to the Welser family, who in return received the land as a colony. Klein-VenedigVenezuela, with fortresses and settlements. They organised expeditions to discover the legendary land of gold El Dorado to discover. In order to get as much as possible out of their fiefdom, they established trading posts to participate in the profitable transatlantic slave trade between Europe, West Africa and America. Although Charles V prohibited trade with indigenous people from South Africa after 1530, the use of African slaves on the plantations and in the mines was not covered by this regulation. The brutal behaviour of the Welser led to complaints at the imperial court in 1546, where they were denied the fiefdom for Klein-Venedig was subsequently withdrawn. However, their trade relations remained intact.

Ferdinand and Philippine met at a carnival ball in Pilsen. The Habsburg fell head over heels in love with the wealthy woman from Augsburg and married her. Nobody in the House of Habsburg was particularly pleased about the couple's secret marriage, even though the business relationships between the aristocrats and the newly rich Augsburg merchants were already several decades old and the Welser's money could be put to good use. Marriages between commoners and aristocrats were considered scandalous and not befitting their status, despite their wealth. The Tyrolean prince is said to have been infatuated with his beautiful wife all his life, which is why he disregarded all conventions of the time. The emperor only recognised the marriage after the couple had asked for forgiveness for their marriage and pledged themselves to eternal secrecy. The children of the morganatic marriage were therefore excluded from the succession. Philippine was considered extremely beautiful. According to contemporary witnesses, her skin was so delicate that „man hätte einen Schluck Rotwein durch ihre Kehle fließen sehen können“. Ferdinand had Ambras Castle remodelled into its present form for his wife. His brother Maximilian even said that "Ferdinand verzaubert sai" by the beautiful Philippine Welser when Ferdinand withdrew his troops during the Turkish war to go home to his wife. The epilogue is less flattering "...I wanted the brekin to be in a sakh and what not. God forgive me."

Philippine Welser's passion was cooking. There is still a collection of recipes in the Austrian National Library today. In the Middle Ages and early modern times, the art of cookery was practised exclusively by the wealthy and aristocrats, while the vast majority of subjects had to eat whatever was available. The Middle Ages and modern times, in fact all people up until the 1950s, lived with a permanent lack of calories. Whereas today we eat too much and get ill as a result, our ancestors suffered from illnesses caused by malnutrition. Fruit was just as rare on the menu as meat. The food was monotonous and hardly flavoured. Spices such as exotic pepper were luxury goods that ordinary people could not afford. While the diet of the ordinary citizen was a dull affair, where the main aim was to get the calories for the daily work as efficiently as possible, the attitude towards food and drink began to change in Innsbruck under Ferdinand II and Philippine Welser. The court had contributed to a certain cultivation of manners and customs in Innsbruck since Frederick IV, and Philippine Welser and Ferdinand took this development to the extreme at Ambras Castle and Weiherburg Castle. The banquets they organised were legendary and often degenerated into orgies.

Herbalism was her second hobbyhorse. Philippine Welser described how to use plants and herbs to alleviate physical ailments of all kinds. "To whiten and freshen the teeth and kill the worms in them: Take rosemary wood and burn it to charcoal, crush it all to powder, bind it in a silken cloth and rub the teeth with itwas one of her tips for a healthy and cultivated existence. She had a herb garden created at Ambras Castle in Innsbruck for her hobby and her studies.

According to reports of the time, she was very popular among the Tyrolean population, as she took great care of the poor and needy. The care of the needy, led by the town council and sponsored by wealthy citizens and aristocrats, was not a speciality at the time, but common practice. Closer to salvation in the next life than through Christian charity, Caritasyou could not come.

, konnte man nicht kommen. Ihre letzte Ruhe fand Philippine Welser nach ihrem Tod 1580 in der Silbernen Kapelle in der Innsbrucker Hofkirche. Gemeinsam mit ihren als Säugling verstorbenen Kindern und Ferdinand wurde sie dort begraben. Unterhalb des Schloss Ambras erinnert die Philippine-Welser-Straße an sie.

Believe, Church and Power

Die Fülle an Kirchen, Kapellen, Kruzifixen und Wandmalereien im öffentlichen Raum wirkt auf viele Besucher Innsbrucks aus anderen Ländern eigenartig. Nicht nur Gotteshäuser, auch viele Privathäuser sind mit Darstellungen der Heiligen Familie oder biblischen Szenen geschmückt. Der christliche Glaube und seine Institutionen waren in ganz Europa über Jahrhunderte alltagsbestimmend. Innsbruck als Residenzstadt der streng katholischen Habsburger und Hauptstadt des selbsternannten Heiligen Landes Tirol wurde bei der Ausstattung mit kirchlichen Bauwerkern besonders beglückt. Allein die Dimension der Kirchen umgelegt auf die Verhältnisse vergangener Zeiten sind gigantisch. Die Stadt mit ihren knapp 5000 Einwohnern besaß im 16. Jahrhundert mehrere Kirchen, die in Pracht und Größe jedes andere Gebäude überstrahlte, auch die Paläste der Aristokratie. Das Kloster Wilten war ein Riesenkomplex inmitten eines kleinen Bauerndorfes, das sich darum gruppierte. Die räumlichen Ausmaße der Gotteshäuser spiegelt die Bedeutung im politischen und sozialen Gefüge wider.

Die Kirche war für viele Innsbrucker nicht nur moralische Instanz, sondern auch weltlicher Grundherr. Der Bischof von Brixen war formal hierarchisch dem Landesfürsten gleichgestellt. Die Bauern arbeiteten auf den Landgütern des Bischofs wie sie auf den Landgütern eines weltlichen Fürsten für diesen arbeiteten. Damit hatte sie die Steuer- und Rechtshoheit über viele Menschen. Die kirchlichen Grundbesitzer galten dabei nicht als weniger streng, sondern sogar als besonders fordernd gegenüber ihren Untertanen. Gleichzeitig war es auch in Innsbruck der Klerus, der sich in großen Teilen um das Sozialwesen, Krankenpflege, Armen- und Waisenversorgung, Speisungen und Bildung sorgte. Der Einfluss der Kirche reichte in die materielle Welt ähnlich wie es heute der Staat mit Finanzamt, Polizei, Schulwesen und Arbeitsamt tut. Was uns heute Demokratie, Parlament und Marktwirtschaft sind, waren den Menschen vergangener Jahrhunderte Bibel und Pfarrer: Eine Realität, die die Ordnung aufrecht hält. Zu glauben, alle Kirchenmänner wären zynische Machtmenschen gewesen, die ihre ungebildeten Untertanen ausnützten, ist nicht richtig. Der Großteil sowohl des Klerus wie auch der Adeligen war fromm und gottergeben, wenn auch auf eine aus heutiger Sicht nur schwer verständliche Art und Weise. Verletzungen der Religion und Sitten wurden in der späten Neuzeit vor weltlichen Gerichten verhandelt und streng geahndet. Die Anklage bei Verfehlungen lautete Häresie, worunter eine Vielzahl an Vergehen zusammengefasst wurde. Sodomie, also jede sexuelle Handlung, die nicht der Fortpflanzung diente, Zauberei, Hexerei, Gotteslästerung – kurz jede Abwendung vom rechten Gottesglauben, konnte mit Verbrennung geahndet werden. Das Verbrennen sollte die Verurteilten gleichzeitig reinigen und sie samt ihrem sündigen Treiben endgültig vernichten, um das Böse aus der Gemeinschaft zu tilgen. Bis in die Angelegenheiten des täglichen Lebens regelte die Kirche lange Zeit das alltägliche Sozialgefüge der Menschen. Kirchenglocken bestimmten den Zeitplan der Menschen. Ihr Klang rief zur Arbeit, zum Gottesdienst oder informierte als Totengeläut über das Dahinscheiden eines Mitglieds der Gemeinde. Menschen konnten einzelne Glockenklänge und ihre Bedeutung voneinander unterscheiden. Sonn- und Feiertage strukturierten die Zeit. Fastentage regelten den Speiseplan. Familienleben, Sexualität und individuelles Verhalten hatten sich an den von der Kirche vorgegebenen Moral zu orientieren. Das Seelenheil im nächsten Leben war für viele Menschen wichtiger als das Lebensglück auf Erden, war dies doch ohnehin vom determinierten Zeitgeschehen und göttlichen Willen vorherbestimmt. Fegefeuer, letztes Gericht und Höllenqualen waren Realität und verschreckten und disziplinierten auch Erwachsene.

Während das Innsbrucker Bürgertum von den Ideen der Aufklärung nach den Napoleonischen Kriegen zumindest sanft wachgeküsst wurde, blieb der Großteil der Menschen weiterhin der Mischung aus konservativem Katholizismus und abergläubischer Volksfrömmigkeit verbunden. Religiosität war nicht unbedingt eine Frage von Herkunft und Stand, wie die gesellschaftlichen, medialen und politischen Auseinandersetzungen entlang der Bruchlinie zwischen Liberalen und Konservativ immer wieder aufzeigten. Seit der Dezemberverfassung von 1867 war die freie Religionsausübung zwar gesetzlich verankert, Staat und Religion blieben aber eng verknüpft. Die Wahrmund-Affäre, die sich im frühen 20. Jahrhundert ausgehend von der Universität Innsbruck über die gesamte K.u.K. Monarchie ausbreitete, war nur eines von vielen Beispielen für den Einfluss, den die Kirche bis in die 1970er Jahre hin ausübte. Kurz vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg nahm diese politische Krise, die die gesamte Monarchie erfassen sollte in Innsbruck ihren Anfang. Ludwig Wahrmund (1861 – 1932) war Ordinarius für Kirchenrecht an der Juridischen Fakultät der Universität Innsbruck. Wahrmund, vom Tiroler Landeshauptmann eigentlich dafür ausgewählt, um den Katholizismus an der als zu liberal eingestuften Innsbrucker Universität zu stärken, war Anhänger einer aufgeklärten Theologie. Im Gegensatz zu den konservativen Vertretern in Klerus und Politik sahen Reformkatholiken den Papst nur als spirituelles Oberhaupt, nicht aber als weltlich Instanz, an. Studenten sollten nach Wahrmunds Auffassung die Lücke und die Gegensätze zwischen Kirche und moderner Welt verringern, anstatt sie einzuzementieren. Seit 1848 hatten sich die Gräben zwischen liberal-nationalen, sozialistischen, konservativen und reformorientiert-katholischen Interessensgruppen und Parteien vertieft. Eine der heftigsten Bruchlinien verlief durch das Bildungs- und Hochschulwesen entlang der Frage, wie sich das übernatürliche Gebaren und die Ansichten der Kirche, die noch immer maßgeblich die Universitäten besetzten, mit der modernen Wissenschaft vereinbaren ließen. Liberale und katholische Studenten verachteten sich gegenseitig und krachten immer aneinander. Bis 1906 war Wahrmund Teil der Leo-Gesellschaft, die die Förderung der Wissenschaft auf katholischer Basis zum Ziel hatte, bevor er zum Obmann der Innsbrucker Ortsgruppe des Vereins Freie Schule wurde, der für eine komplette Entklerikalisierung des gesamten Bildungswesens eintrat. Vom Reformkatholiken wurde er zu einem Verfechter der kompletten Trennung von Kirche und Staat. Seine Vorlesungen erregten immer wieder die Aufmerksamkeit der Obrigkeit. Angeheizt von den Medien fand der Kulturkampf zwischen liberalen Deutschnationalisten, Konservativen, Christlichsozialen und Sozialdemokraten in der Person Ludwig Wahrmunds eine ideale Projektionsfläche. Was folgte waren Ausschreitungen, Streiks, Schlägereien zwischen Studentenverbindungen verschiedener Couleur und Ausrichtung und gegenseitige Diffamierungen unter Politikern. Die Los-von-Rom Bewegung des Deutschradikalen Georg Ritter von Schönerer (1842 – 1921) krachte auf der Bühne der Universität Innsbruck auf den politischen Katholizismus der Christlichsozialen. Die deutschnationalen Akademiker erhielten Unterstützung von den ebenfalls antiklerikalen Sozialdemokraten sowie von Bürgermeister Greil, auf konservativer Seite sprang die Tiroler Landesregierung ein. Die Wahrmund Affäre schaffte es als Kulturkampfdebatte bis in den Reichsrat. Für Christlichsoziale war es ein „Kampf des freissinnigen Judentums gegen das Christentum“ in dem sich „Zionisten, deutsche Kulturkämpfer, tschechische und ruthenische Radikale“ in einer „internationalen Koalition“ als „freisinniger Ring des jüdischen Radikalismus und des radikalen Slawentums“ präsentierten. Wahrmund hingegen bezeichnete in der allgemein aufgeheizten Stimmung katholische Studenten als „Verräter und Parasiten“. Als Wahrmund 1908 eine seiner Reden, in der er Gott, die christliche Moral und die katholische Heiligenverehrung anzweifelte, in Druck bringen ließ, erhielt er eine Anzeige wegen Gotteslästerung. Nach weiteren teils gewalttätigen Versammlungen sowohl auf konservativer und antiklerikaler Seite, studentischen Ausschreitungen und Streiks musste kurzzeitig sogar der Unibetrieb eingestellt werden. Wahrmund wurde zuerst beurlaubt, später an die deutsche Universität Prag versetzt.

Auch in der Ersten Republik war die Verbindung zwischen Kirche und Staat stark. Der christlichsoziale, als Eiserner Prälat in die Geschichte eingegangen Ignaz Seipel schaffte es in den 1920er Jahren bis ins höchste Amt des Staates. Bundeskanzler Engelbert Dollfuß sah seinen Ständestaat als Konstrukt auf katholischer Basis als Bollwerk gegen den Sozialismus. Auch nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg waren Kirche und Politik in Person von Bischof Rusch und Kanzler Wallnöfer ein Gespann. Erst dann begann eine ernsthafte Trennung. Glaube und Kirche haben noch immer ihren fixen Platz im Alltag der Innsbrucker, wenn auch oft unbemerkt. Die Kirchenaustritte der letzten Jahrzehnte haben der offiziellen Mitgliederzahl zwar eine Delle versetzt und Freizeitevents werden besser besucht als Sonntagsmessen. Die römisch-katholische Kirche besitzt aber noch immer viel Grund in und rund um Innsbruck, auch außerhalb der Mauern der jeweiligen Klöster und Ausbildungsstätten. Etliche Schulen in und rund um Innsbruck stehen ebenfalls unter dem Einfluss konservativer Kräfte und der Kirche. Und wer immer einen freien Feiertag genießt, ein Osterei ans andere peckt oder eine Kerze am Christbaum anzündet, muss nicht Christ sein, um als Tradition getarnt im Namen Jesu zu handeln.

The year 1848 and its consequences

The year 1848 occupies a mythical place in European history. Although the hotspots were not to be found in secluded Tyrol, but in the major metropolises such as Paris, Vienna, Budapest, Milan and Berlin, even in the Holy Land however, the revolutionary year left its mark. In contrast to the rural surroundings, an enlightened educated middle class had developed in Innsbruck. Enlightened people no longer wanted to be subjects of a monarch or sovereign, but citizens with rights and duties towards the state. Students and freelancers demanded political participation, freedom of the press and civil rights. Workers demanded better wages and working conditions. Radical liberals and nationalists in particular even questioned the omnipotence of the church.

In March 1848, this socially and politically highly explosive mixture erupted in riots in many European cities. In Innsbruck, students and professors celebrated the newly enacted freedom of the press with a torchlight procession. On the whole, however, the revolution proceeded calmly in the leisurely Tyrol. It would be foolhardy to speak of a spontaneous outburst of emotion; the date of the procession was postponed from 20 to 21 March due to bad weather. There were hardly any anti-Habsburg riots or attacks; a stray stone thrown into a Jesuit window was one of the highlights of the Alpine version of the 1848 revolution. The students even helped the city magistrate to monitor public order in order to show their gratitude to the monarch for the newly granted freedoms and their loyalty.

The initial enthusiasm for bourgeois revolution was quickly replaced by German nationalist, patriotic fervour in Innsbruck. On 6 April 1848, the German flag was waved by the governor of Tyrol during a ceremonial procession. A German flag was also raised on the city tower. Tricolour was hoisted. While students, workers, liberal-nationalist-minded citizens, republicans, supporters of a constitutional monarchy and Catholic conservatives disagreed on social issues such as freedom of the press, they shared a dislike of the Italian independence movement that had spread from Piedmont and Milan to northern Italy. Innsbruck students and marksmen marched to Trentino with the support of the k.k. The Innsbruck students and riflemen moved into Trentino to nip the unrest and uprisings in the bud. Well-known members of this corps were Father Haspinger, who had already fought with Andreas Hofer in 1809, and Adolf Pichler. Johann Nepomuk Mahl-Schedl, wealthy owner of Büchsenhausen Castle, even equipped his own company with which he marched across the Brenner Pass to secure the border.

The city of Innsbruck, as the political and economic centre of the multinational crown land of Tyrol and home to many Italian speakers, also became the arena of this nationality conflict. Combined with copious amounts of alcohol, anti-Italian sentiment in Innsbruck posed more of a threat to public order than civil liberties. A quarrel between a German-speaking craftsman and an Italian-speaking Ladin got so heated that it almost led to a pogrom against the numerous businesses and restaurants owned by Italian-speaking Tyroleans.

The relative tranquillity of Innsbruck suited the imperial house, which was under pressure. When things did not stop boiling in Vienna even after March, Emperor Ferdinand fled to Tyrol in May. According to press reports from this time, he was received enthusiastically by the population.

"Wie heißt das Land, dem solche Ehre zu Theil wird, wer ist das Volk, das ein solches Vertrauen genießt in dieser verhängnißvollen Zeit? Stützt sich die Ruhe und Sicherheit hier bloß auf die Sage aus alter Zeit, oder liegt auch in der Gegenwart ein Grund, auf dem man bauen kann, den der Wind nicht weg bläst, und der Sturm nicht erschüttert? Dieses Alipenland heißt Tirol, gefällts dir wohl? Ja, das tirolische Volk allein bewährt in der Mitte des aufgewühlten Europa die Ehrfurcht und Treue, den Muth und die Kraft für sein angestammtes Regentenhaus, während ringsum Auflehnung, Widerspruch. Trotz und Forderung, häufig sogar Aufruhr und Umsturz toben; Tirol allein hält fest ohne Wanken an Sitte und Gehorsam, auf Religion, Wahrheit und Recht, während anderwärts die Frechheit und Lüge, der Wahnsinn und die Leidenschaften herrschen anstatt folgen wollen. Und während im großen Kaiserreiche sich die Bande überall lockern, oder gar zu lösen drohen; wo die Willkühr, von den Begierden getrieben, Gesetze umstürzt, offenen Aufruhr predigt, täglich mit neuen Forderungen losgeht; eigenmächtig ephemere- wie das Wetter wechselnde Einrichtungen schafft; während Wien, die alte sonst so friedliche Kaiserstadt, sich von der erhitzten Phantasie der Jugend lenken und gängeln läßt, und die Räthe des Reichs auf eine schmähliche Weise behandelt, nach Laune beliebig, und mit jakobinischer Anmaßung, über alle Provinzen verfügend, absetzt und anstellt, ja sogar ohne Ehrfurcht, den Kaiaer mit Sturm-Petitionen verfolgt; während jetzt von allen Seiten her Deputationen mit Ergebenheits-Addressen mit Bittgesuchen und Loyalitätsversicherungen dem Kaiser nach Innsbruck folgen, steht Tirol ganz ruhig, gleich einer stillen Insel, mitten im brausenden Meeressturme, und des kleinen Völkchens treue Brust bildet, wie seine Berge und Felsen, eine feste Mauer in Gesetz und Ordnung, für den Kaiser und das Vaterland."

In June, a young Franz Josef, not yet emperor at the time, also stayed at the Hofburg on his way back from the battlefields of northern Italy instead of travelling directly to Vienna. Innsbruck was once again the royal seat, if only for one summer. While blood was flowing in Vienna, Milan and Budapest, the imperial family enjoyed life in the Tyrolean countryside. Ferdinand, Franz Karl, his wife Sophie and Franz Josef received guests from foreign royal courts and were chauffeured in four-in-hand carriages to the region's excursion destinations such as Weiherburg Castle, Stefansbrücke Bridge, Kranebitten and high up to Heiligwasser. A little later, however, the cosy atmosphere came to an end. Under gentle pressure, Ferdinand, who was no longer considered fit for office, passed the torch of regency to Franz Josef I. In July 1848, the first parliamentary session was held in the Court Riding School in Vienna. The first constitution was enacted. However, the monarchy's desire for reform quickly waned. The new parliament was an imperial council, it could not pass any binding laws, the emperor never attended it during his lifetime and did not understand why the Danube Monarchy, as a divinely appointed monarchy, needed this council.

Nevertheless, the liberalisation that had been gently set in motion took its course in the cities. Innsbruck was given the status of a town with its own statute. Innsbruck's municipal law provided for a right of citizenship that was linked to ownership or the payment of taxes, but legally guaranteed certain rights to members of the community. Birthright citizenship could be acquired by birth, marriage or extraordinary conferment and at least gave male adults the right to vote at municipal level. If you got into financial difficulties, you had the right to basic support from the town.

Thanks to the census-based majority voting system, the Greater German liberal faction prevailed within the city government, in which merchants, tradesmen, industrialists and innkeepers set the tone. On 2 June 1848, the first edition of the liberal and Greater German-minded Innsbrucker Zeitungfrom which the above article on the emperor's arrival in Innsbruck is taken. Conservatives, on the other hand, read the Volksblatt for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. Moderate readers who favoured a constitutional monarchy preferred to consume the Bothen for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. However, the freedom of the press soon came to an end. The previously abolished censorship was reintroduced in parts. Newspaper publishers had to undergo some harassment by the authorities. Newspapers were not allowed to write against the state government, monarchy or church.

"Anyone who, by means of printed matter, incites, instigates or attempts to incite others to take action which would bring about the violent separation of a part from the unified state... of the Austrian Empire... or the general Austrian Imperial Diet or the provincial assemblies of the individual crown lands.... Imperial Diet or the Diet of the individual Crown Lands... violently disrupts... shall be punished with severe imprisonment of two to ten years."

After Innsbruck officially replaced Meran as the provincial capital in 1849 and thus finally became the political centre of Tyrol, political parties were formed. From 1868, the liberal and Greater German orientated party provided the mayor of the city of Innsbruck. The influence of the church declined in Innsbruck in contrast to the surrounding communities. Individualism, capitalism, nationalism and consumerism stepped into the breach. New worlds of work, department stores, theatres, cafés and dance halls did not supplant religion in the city either, but the emphasis changed as a result of the civil liberties won in 1848.

Perhaps the most important change to the law was the Basic relief patent. In Innsbruck, the clergy, above all Wilten Abbey, held a large proportion of the peasant land. The church and nobility were not subject to taxation. In 1848/49, manorial rule and servitude were abolished in Austria. Land rents, tithes and roboters were thus abolished. The landlords received one third of the value of their land from the state as part of the land relief, one third was regarded as tax relief and the farmers had to pay one third of the relief themselves. They could pay off this amount in instalments over a period of twenty years.

The after-effects can still be felt today. The descendants of the then successful farmers enjoy the fruits of prosperity through inherited land ownership, which can be traced back to the land relief of 1848, as well as political influence through land sales for housing construction, leases and public sector redemptions for infrastructure projects. The land-owning nobles of the past had to resign themselves to the ignominy of pursuing middle-class labour. The transition from birthright to privileged status within society was often successful thanks to financial means, networks and education. Many of Innsbruck's academic dynasties began in the decades after 1848.

Das bis dato unbekannte Phänomen der Freizeit kam, wenn auch für den größten Teil nur spärlich, auf und begünstigte gemeinsam mit frei verfügbarem Einkommen einer größeren Anzahl an Menschen Hobbies. Zivile Organisationen und Vereine, vom Lesezirkel über Sängerbünde, Feuerwehren und Sportvereine, gründeten sich. Auch im Stadtbild manifestierte sich das Revolutionsjahr. Parks wie der Englische Garten beim Schloss Ambras oder der Hofgarten waren nicht mehr exklusiv der Aristokratie vorbehalten, sondern dienten den Bürgern als Naherholungsgebiete vom beengten Dasein. In St. Nikolaus entstand der Waltherpark als kleine Ruheoase. Einen Stock höher eröffnete im Schloss Büchsenhausen Tirols erste Schwimm- und Badeanstalt, wenig später folgte ein weiteres Bad in Dreiheiligen. Ausflugsgasthöfe rund um Innsbruck florierten. Neben den gehobenen Restaurants und Hotels entstand eine Szene aus Gastwirtschaften, in denen sich auch Arbeiter und Angestellte gemütliche Abende bei Theater, Musik und Tanz leisten konnten.