Art in architecture: the post-war period

Art in architecture: the post-war period in Innsbruck

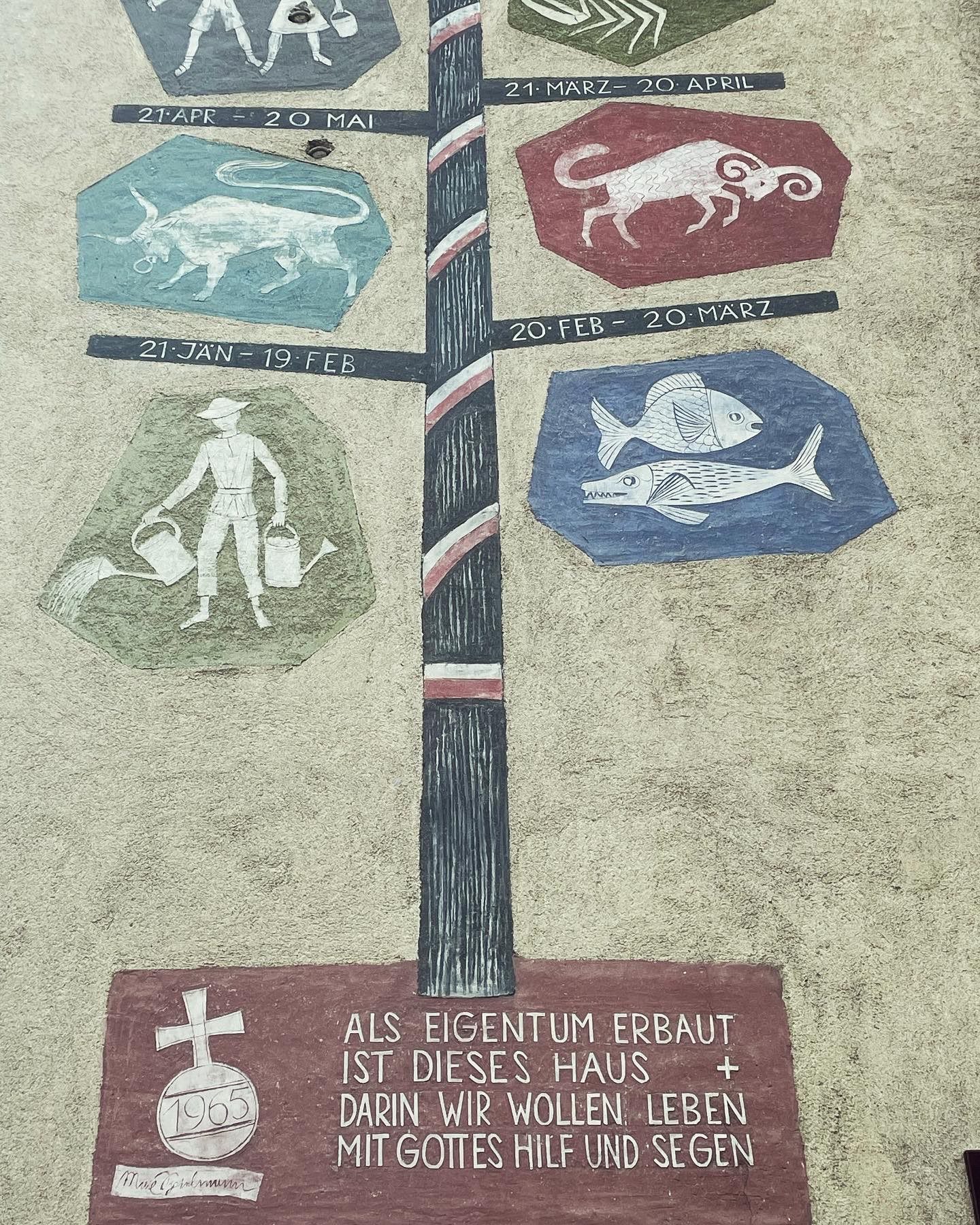

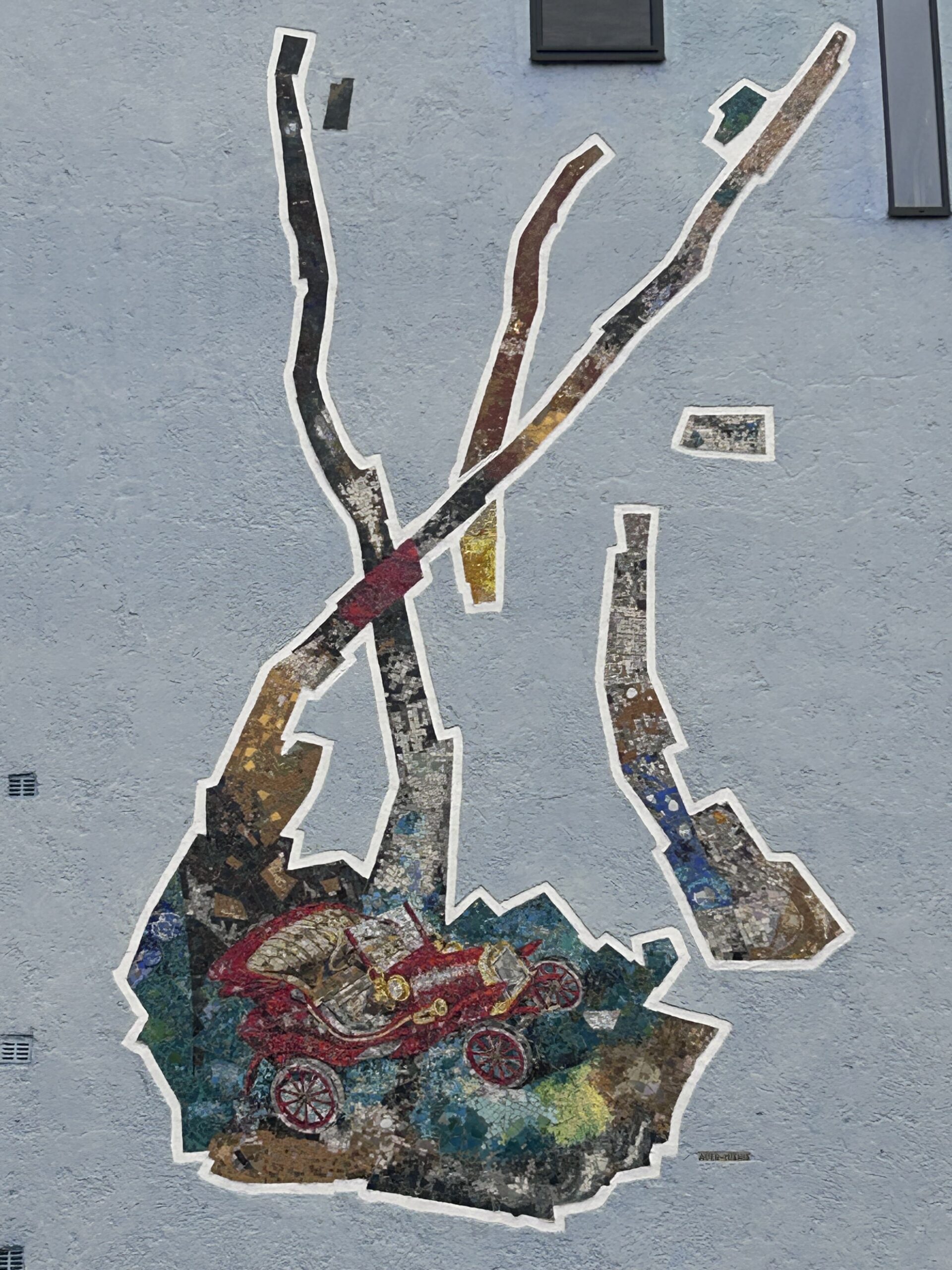

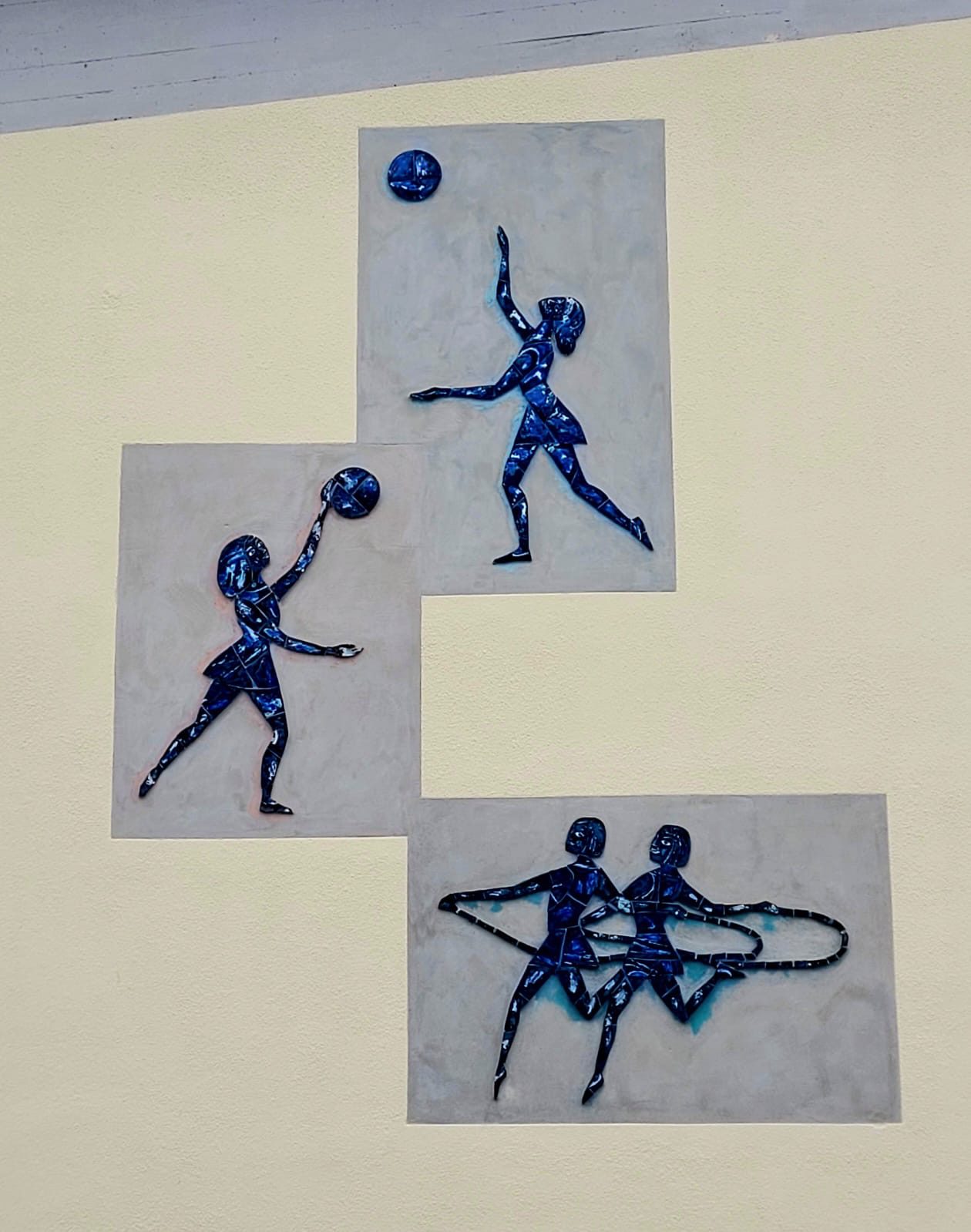

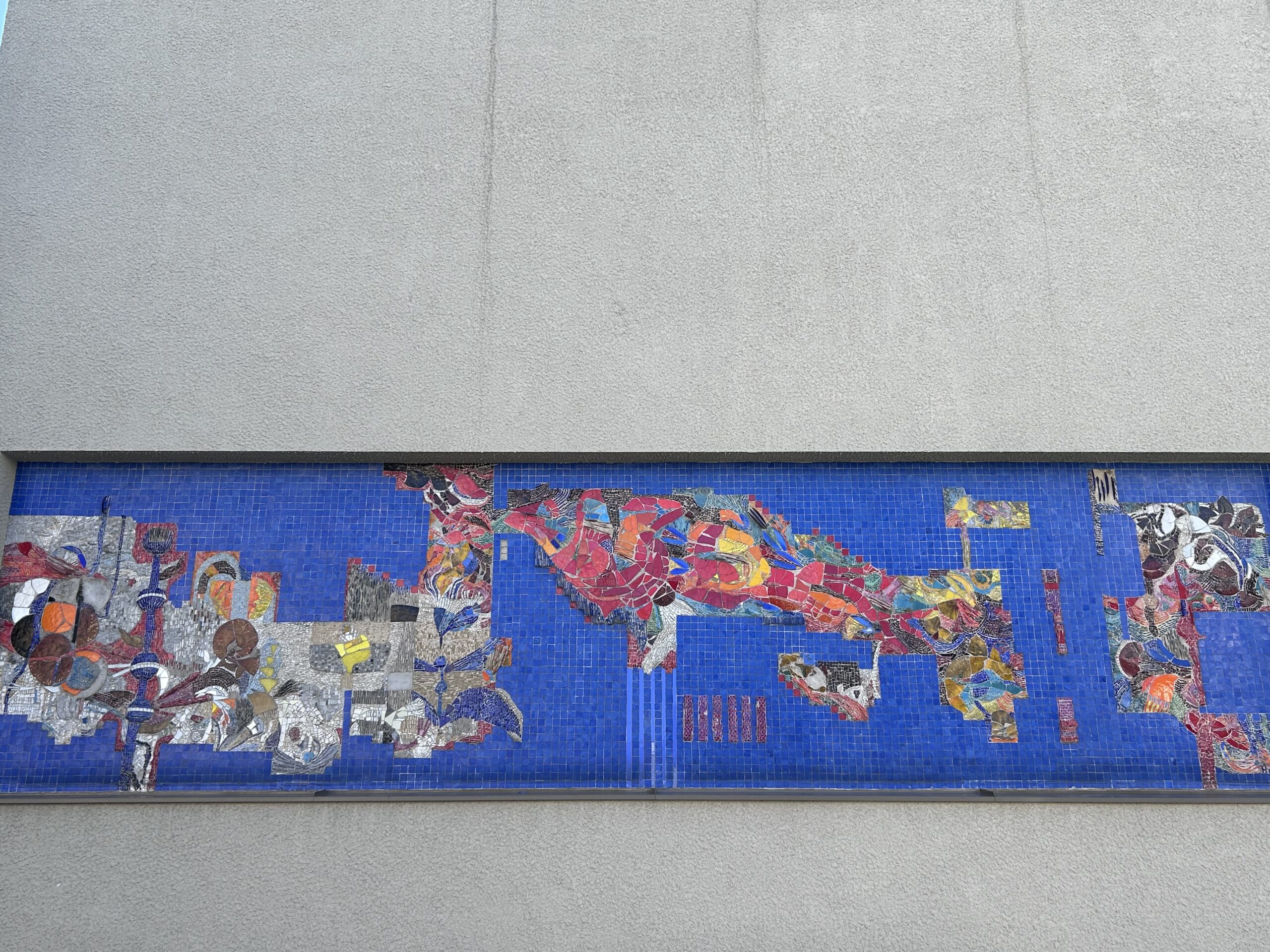

As after World War I, housing shortages were one of the most pressing problems after 1945. Innsbruck had suffered heavy damage during air raids, and money for new construction was scarce. When the first housing complexes were built in the 1950s, thrift was the order of the day. Many of the buildings erected from the 1950s onward may be architecturally unattractive, but they contain interesting artworks. From 1949 onward, Austria implemented the “Art in Architecture” project (Kunst am Bau). For state-funded construction projects, 2% of total expenditures were to be allocated to artistic design. The implementation of building regulations and thus the management of budgets was, as then and now, the responsibility of the federal states. Through these public commissions, artists were to be financially supported. In the lean post-war years, even successful and practically minded artists such as Oswald Haller (1908–1981), who earned money with commercial graphics and tourism posters, faced difficulties. The idea first appeared in 1919 in the Weimar Republic and was continued by the National Socialists from 1934 onward. Austria revived Kunst am Bau after the war to shape public spaces during reconstruction. The public sector, which replaced aristocracy and bourgeoisie as builders of previous centuries, was under massive financial pressure. Nevertheless, the primarily functional housing projects were not to appear entirely without ornamentation. Tyrolean artists entrusted with designing the artworks were selected through public competitions. The most famous among them was Max Weiler, perhaps the most prominent artist in post-war Tyrol, responsible for the frescoes in the Theresienkirche on the Hungerburg in Innsbruck. Other notable names include Helmut Rehm (1911–1991), Walter Honeder (1906–2006), Fritz Berger (1916–2002), and Emmerich Kerle (1916–2010). Many of these artists were shaped not only by the Federal Trade School in Innsbruck (today’s HTL) and the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna but also by the collective experience of National Socialism and the war. Fritz Berger had lost his right arm and an eye and had to learn to work with his left hand. Kerle served in Finland as a war painter and was taught at the Academy by Josef Müllner, an artist who entered art history with busts of Adolf Hitler, Siegfried from the Nibelungen saga, and the still controversial Karl Lueger monument in Vienna. Like much of the Tyrolean population, these artists—as well as politicians and officials—wanted peace and quiet after the harsh and painful war years, to let the grass grow over the events of the past decades. The works created under Kunst am Bau reflect this attitude toward a new moral order. It was the first time abstract, formless art entered Innsbruck’s public space, albeit only in an uncritical context. Fairy tales, legends, and religious symbols were popular motifs immortalized in sgraffitos, mosaics, murals, and statues. One could speak of a kind of second wave of Biedermeier art, symbolizing the petty-bourgeois lifestyle of people after the war. Art was also intended to create a new awareness and image of what was considered typically Austrian. As late as 1955, every second Austrian still regarded themselves as German. The various motifs depict leisure activities, clothing styles, and notions of social order and norms of the post-war era. Women were often shown in traditional dress and dirndls, men in lederhosen. Conservative ideals of gender roles were reflected in the art: hardworking fathers, dutiful wives caring for home and hearth, and children diligently learning at school were the ideal image well into the 1970s—a life like in a Peter Alexander film. Those who walk attentively through the city will find many of these still-visible artworks on houses in Pradl and Wilten. The mix of unremarkable architecture and contemporary artworks from the often-suppressed, long-idealized post-war era is worth seeing. Particularly beautiful examples can be found on façades in Pacherstraße, Hunoldstraße, Ing.-Thommenstraße, Innrain, at the Landesberufsschule Mandelsbergerstraße, or in the courtyard between Landhausplatz and Maria-Theresien-Straße.

Directory Art in Architecture 1950s and 1960s

If you are missing a work of art, we would be delighted to hear from you at info@discover-innsbruck.at

Wilten & Höttinger Au

- Egger-Lienz-Straße 48 and 119

- Innrain 87, 91, 109, 119 and 135

- Mandelsbergerstraße state vocational school

- Doktor-Karl-von-Grabmayer-Straße

- Karmelitergasse 6

- Andreas Hofer-Strasse 24 - 28

- Ing.-Thommen-Strasse 4 and 5

- Hormayrstrasse 15

- Noldinstrasse 2 and 4

- Leopoldstrasse 41 a

- Leopoldstraße 43 (Pechepark kindergarten)

- Freisingstraße 8

- Andreas-Hofer-Straße 47

- Innerkoflerstrasse / Schöpfstrasse

- WIFI Construction Academy Apprentice Centre

- Clinic Innsbruck

- Horse fountain Wilten West parish

- Bachlechnerstrasse 24

Pradl

- Hunoldstraße 20

- Knollerstraße 1 (passageway)

- Amraserstraße 23 a

- Pacherstrasse 16 and 18

- Gumppstrasse 3

- Dr.-Glatz-Straße 16

- Kindergarten Lönsstraße

- Siegmair School Pradl East

- Roseggerstrasse 23

- Grenzstrasse 24

- Amraserstraße 77

- Gerhard-Hauptmann-Straße 7

- Amraserstraße 88

- Gabelsbergerstrasse 3

Old Town

- Riesengasse 3 / 5 / 8

City Center

- Landhauspassage (between Maria-Theresien-Straße and Landhaus)

- Landhausplatz

- Blasius-Hueber-Strasse 8

Saggen

- Hotel Clima Zeughausgasse 3

St. Nikolaus / Mariahilf / Hötting

- Innstrasse 63

- Höttingergasse 39

- Bachgasse

Sights to see...

Leopoldstraße & Wiltener Platzl

Leopoldstrasse

Provincial vocational school

Mandelsbergerstrasse 16

Landhausplatz & Tiroler Landhaus

Eduard Wallnöfer Square