Guardian Angel Church

Gumppstrasse 67

Worth knowing

Between 1939 and 1942, a new neighbourhood was built in the east of Innsbruck between Langstraße, Roßsprung and Kranewitterstraße. South Tyrolean settlement Pradl. As in Wilten West, Saggen and Reichenau, the striking blocks of flats grouped around generously designed inner courtyards were built at lightning speed to warmly welcome German-speaking resettlers from South Tyrol to the capital of the Reichsgau Tyrol and Vorarlberg. Despite all the National Socialist attention to detail in the planning of the huge housing estate, Christian pastoral care was not taken into consideration. When the Catholic Church celebrated its revival after 1945 and Sunday services made their return to everyday social life, the Pradl parish church proved to be far too small for the new neighbourhood that had sprung up and its residents. In 1950, the Apostolic Administrator and later Bishop Paulus Rusch therefore divided the bloated parish in two, with Neu-Pradl initially only being a vicariate and not a parish in its own right. In the same year, construction work began on the first newly built church of the post-war period.

Architect Karl Friedrich Albert planned the Parish Church of the Holy Guardian Angels in a kind of neo-Romanesque style. The entrance area consists of three arches crowned by a round window. Round shapes also characterise the sturdy church tower. The basic form of the building is thus based on a traditional, deliberately unobtrusive approach rather than demonstrating a new departure. After the horrors of war, harmony was the order of the day. The austere exterior also reflects the difficult economic situation of the early post-war years. This distinguishes the Schutzengelkirche from later, much more modern and daring designs such as St Norbert in Pradl Süd, the parish church of the Holy Family at Wilten West cemetery or even Horst Parson's Petrus Canisius church in Höttinger Au.

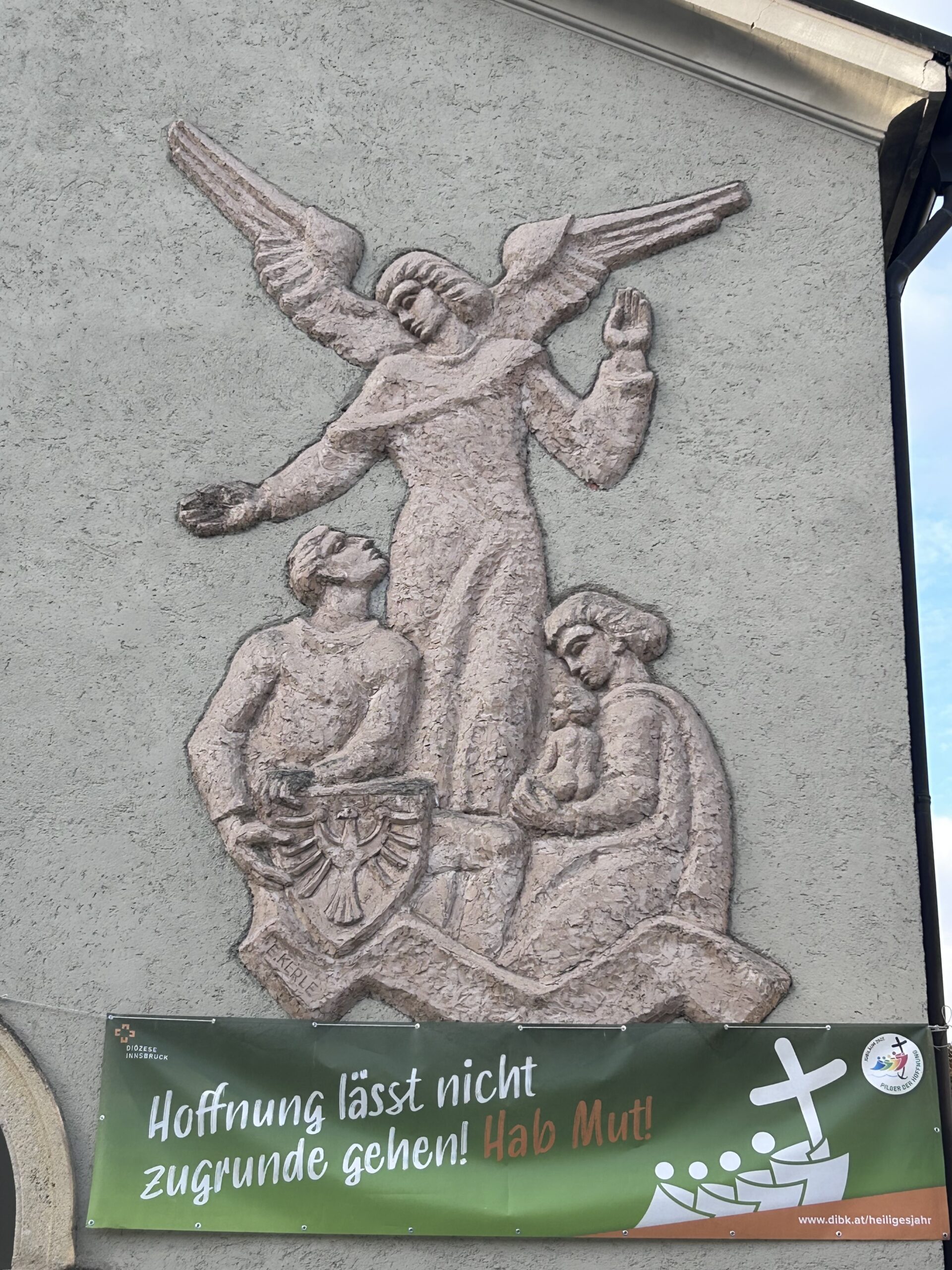

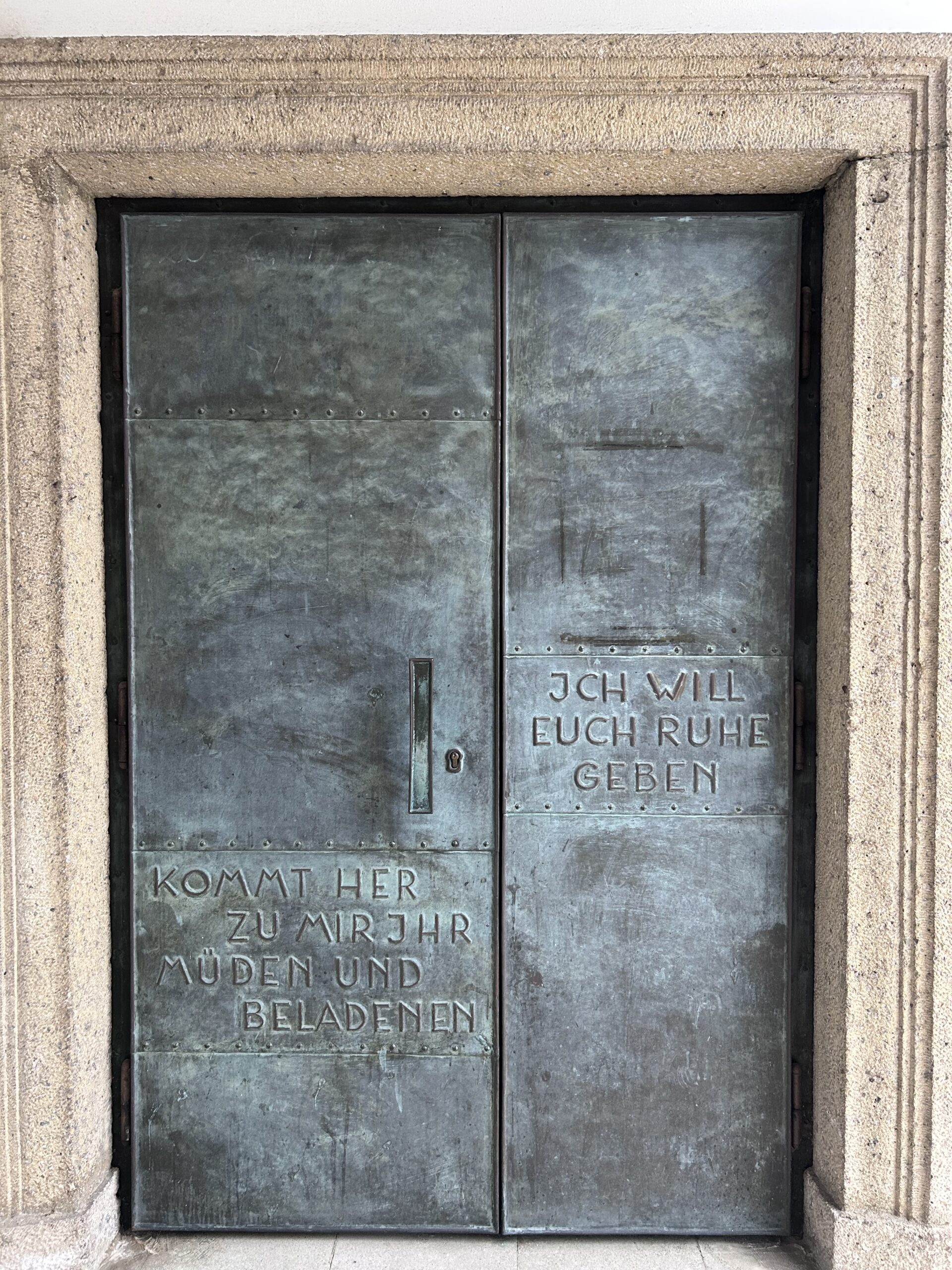

The church was consecrated in 1952 before it was finally completed. The striking relief on the façade was not added until 1956. Here, too, the decision was made in favour of a traditional and conservative design. The scandal surrounding Max Weiler's paintings in the interior design of the Theresienkirche on the Hungerburg a few years earlier was still fresh in the minds of those responsible and a proven, conservative artist was chosen. Emmerich Kerle, who in addition to many sacred works also designed the façade of the Mandelsbergerstraße vocational school and the eagle on the Liberation Monument on Landhausplatz, had his workshop in the basement of the Schutzengelkirche. The motif he chose for the church symbolises the spirit of the 1950s, which can be found in many of the works in the Kunst am Bau campaign. The guardian angel holds his protective hand over a well-behaved family and the Tyrolean coat of arms. On the left-hand side of the interior, next to the entrance, there is a classic altar for the veneration of the Virgin Mary. The ornate stained glass windows depict Pope Pius X (1835 - 1914), flanked by St Theresa and St Francis. Pius was regarded as a defender of the church against modernity. When he was elected, Emperor Franz Josef I vetoed his opponent, thus making Pius„ election possible. His church policy was also on the same wavelength as Tyrol's highest cleric Paulus Rusch, who would later dedicate a church in Reichenau to him. The rest of the interior and the gallery are almost Protestant in character. The massive entrance portals were also made by Kerle. The centre one shows the four evangelists. The biblical quotation on the side door is probably also in keeping with the spirit of the post-war period: "Come to me, you who are weary and burdened. I will give you rest.“

Risen from the ruins

Nach Kriegsende kontrollierten US-Truppen für zwei Monate Tirol. Anschließend übernahm die Siegermacht Frankreich die Verwaltung. Den Tirolern blieb die sowjetische Besatzung, die über Ostösterreich hereinbrach, erspart. Besonders in den ersten drei Nachkriegsjahren war der Hunger der größte Feind der Menschen. Der Mai 1945 brachte nicht nur das Kriegsende, sondern auch Schnee. Der Winter 1946/47 ging als besonders kalt und lang in die Tiroler Klimageschichte ein, der Sommer als besonders heiß und trocken. Es kam zu Ernteausfällen von bis zu 50%. Die Versorgungslage war vor allem in der Stadt in der unmittelbaren Nachkriegszeit katastrophal. Die tägliche Nahrungsmittelbeschaffung wurde zur lebensgefährlichen Sorge im Alltag der Innsbrucker. Neben den eigenen Bürgern mussten auch tausende von Displaced PersonsThe Tyrolean government had to feed a large number of people, freed forced labourers and occupying soldiers. To accomplish this task, the Tyrolean provincial government had to rely on outside help. The chairman of the UNRRA (Note: United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration), which supplied war zones with essentials, Fiorello La Guardia counted Austria "to those peoples of the world who are closest to starvation." Milk, bread, eggs, sugar, flour, fat - there was too little of everything. The French occupation was unable to meet the demand for the required kilocalories per capita, as the local population and the emergency services often lacked supplies. Until 1946, they even took goods from the Tyrolean economy.

Die Lebensmittelversorgung erfolgte schon wenige Wochen nach Kriegsende über Lebensmittelkarten. Erwachsene mussten eine Bestätigung des Arbeitsamtes vorlegen, um an diese Karten zu kommen. Die Rationen unterschieden sich je nach Kategorie der Arbeiter. Schwerstarbeiter, Schwangere und stillende Mütter erhielten Lebensmittel im „Wert“ von 2700 Kalorien. Handwerker mit leichten Berufen, Beamte und Freiberufler erhielten 1850 Kilokalorien, Angestellte 1450 Kalorien. Hausfrauen und andere „Normalverbraucher“ konnten nur 1200 Kalorien beziehen. Zusätzlich gab es Initiativen wie Volksküchen oder Ausspeisungen für Schulkinder, die von ausländischen Hilfsorganisationen übernommen wurden. Aus Amerika kamen Carepakete von der Wohlfahrtsorganisation Cooperative for American Remittances to Europe. Many children were sent to foster homes in Switzerland in the summer to regain their strength and put a few extra kilos on their ribs.

However, all these measures were not enough for everyone. Housewives and other "normal consumers" in particular suffered from the low allocations. Despite the risk of being arrested, many Innsbruck residents travelled to the surrounding villages to hoard. Those who had money paid sometimes utopian prices to the farmers. Those who had none had to beg for food. In extreme cases, women whose husbands had been killed, captured or were missing saw no other way out than to prostitute themselves. These women, especially the unfortunate ones who became pregnant, had to endure the worst abuse for themselves and their offspring. Austria was still 30 years away from legalised abortion.

Politicians were largely powerless in the face of this. Even in normal times, it was impossible to pacify all interests. Many decisions between the parliament in Vienna, the Tyrolean provincial parliament and Innsbruck town hall were incomprehensible to the people. While children had to do without fruit and vitamins, some farmers legally distilled profitable schnapps. Official buildings and commercial enterprises were given free rein by the Innsbruck electricity company, while private households were restricted access to electricity at several times of the day from October 1945. The same disadvantage for households compared to businesses applied to the supply of coal. The old rifts between town and country grew wider and more hateful. Innsbruckers accused the surrounding population of deliberately withholding food for the black market. There were robberies, thefts and woodcutting. Transports at the railway station were guarded by armed units. Obtaining food from a camp was both illegal and commonplace. Children and young people roamed the city hungry and took every opportunity to get something to eat or fuel. The first Tyrolean governor Gruber, himself an illegal member of the resistance during the war, understood the situation of the people who rebelled against the system, but was unable to do anything about it. The mayor of Innsbruck, Anton Melzer, also had his hands tied. Not only was it difficult to reconcile the needs of all interest groups, there were repeated cases of corruption and favours to relatives and acquaintances among the civil servants. Gruber's successor in the provincial governor's chair, Alfons Weißgatterer, had to survive several small riots when popular anger was vented and stones were thrown in the direction of the Landhaus. Tiroler Tageszeitung. The paper was founded in 1945 under the administration of the US armed forces for the purposes of democratisation and denazification, but was transferred the following year to Schlüssel GmbH under the management of ÖVP politician Joseph Moser. Thanks to the high circulation and its almost direct influence on the content, the Tyrolean provincial government was able to steer the public mood:

„Are the broken windows that clattered from the country house into the street yesterday suitable arguments to prove our will to rebuild? Shouldn't we remember that economic difficulties have never been resolved by demonstrations and rallies in any country?“

The housing situation was at least as bad. An estimated 30,000 Innsbruck residents were homeless, living in cramped conditions with relatives or in shanty towns such as the former labour camp in Reichenau, the shanty town for displaced persons from the former German territories of Europe, popularly known as the "Ausländerlager", or the "Ausländerlager". Bocksiedlung. Weniges erinnert noch an den desaströsen Zustand, in dem sich Innsbruck nach den Luftangriffen der letzten Kriegsjahre in den ersten Nachkriegsjahren befand. Zehntausende Bürger halfen mit, Schutt und Trümmer von den Straßen zu schaffen. Die Maria-Theresien-Straße, die Museumstraße, das Bahnhofsviertel, Wilten oder die Pradlerstraße wären wohl um einiges ansehnlicher, hätte man nicht die Löcher im Straßenbild schnell stopfen müssen, um so schnell als möglich Wohnraum für die vielen Obdachlosen und Rückkehrer zu schaffen. Ästhetik aber war ein Luxus, den man sich in dieser Situation nicht leisten konnte. Die ausgezehrte Bevölkerung benötigte neuen Wohnraum, um den gesundheitsschädlichen Lebensbedingungen, in denen Großfamilien teils in Einraumwohnungen einquartiert waren, zu entfliehen.

"The emergency situation jeopardises the comfort of the home. It eats away at the roots of joie de vivre. No one suffers more than the woman whose happiness is to see a contented, cosy family circle around her. What a strain on mental strength is required by the daily gruelling struggle for a little shopping, the hardship of queuing, the disappointment of rejections and refusals and the look of discouragement on the faces of loved ones tormented by deprivation."

What is in the Tiroler Tageszeitung was only part of the harsh reality of everyday life. As after the First World War, when the Spanish flu claimed many victims, there was also an increase in dangerous infections in 1945. Vaccines against tuberculosis could not be delivered in the first winter. Hospital beds were also in short supply. Even though the situation eased after 1947, living conditions in Tyrol remained precarious. It took years before there were any noticeable improvements. Food rationing was discontinued on 1 July 1953. In the same year, Mayor Greiter was able to announce that all the buildings destroyed during the air raids had been repaired.

This was also thanks to the occupying forces. The French troops under Emile Bethouart behaved very mildly and co-operatively towards the former enemy and were friendly and open-minded towards the Tyrolean culture and population. Initially hostile towards the occupying power - yet another war had been lost - the scepticism of the people of Innsbruck gradually gave way. The soldiers were particularly popular with the children because of the chocolates and sweets they handed out. Many people were given jobs within the French administration. Thanks to the uniformed soldiers, many a Tyrolean saw of the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division, die bis September 1945 den Großteil der Soldaten stellten, zum ersten Mal dunkelhäutige Menschen. Die Besatzer stellten, soweit dies in ihren Möglichkeiten lag, auch die Versorgung sicher. Zeitzeugen erinnern sich mit Grauen an die Konservendosen, die sie als Hauptnahrungsmittel erhielten. Um die Logistik zu erleichtern legten die Franzosen bereits 1946 den Grundstein für den neuen Flughafen auf der Ulfiswiese in der Höttinger Au, der den 20 Jahre zuvor eröffneten in der Reichenau nach zwei Jahren Bauzeit ersetzte. Das Franzosendenkmal am Landhausplatz erinnert an die französische Besatzungszeit. Am Emile Bethouart footbridgeThe memorial plaque on the river Inn, which connects St. Nikolaus and the city centre, is a good expression of the relationship between the occupation and the population:

"Arrived as a winner.

Remained as a protector.

Returned home as a friend."

In addition to material hardship, society was characterised by the collective trauma of war. The adults of the 1950s were products of the education of the interwar period and National Socialism. Men who had fought at the front could only talk about their horrific experiences in certain circles as war losers; women usually had no forum at all to process their fears and worries. Domestic violence and alcoholism were widespread. Teachers, police officers, politicians and civil servants often came from National Socialist supporters, who did not simply disappear with the end of the war, but were merely hushed up in public. On Innsbruck People's Court Although there were a large number of trials against National Socialists under the direction of the victorious powers, the number of convictions did not reflect the extent of what had happened. The majority of those accused went free. Particularly incriminated representatives of the system were sent to prison for some time, but were able to resume their old lives relatively undisturbed after serving their sentences, at least professionally. It was not just a question of drawing a line under the past decades; yesterday's perpetrators were needed to keep today's society running.

The problem with this strategy of suppression was that no one took responsibility for what had happened, even if there was great enthusiasm and support for National Socialism, especially at the beginning. There was hardly a family that did not have at least one member with a less than glorious history between 1933 and 1945. Shame about what had happened since 1938 and in Austria's politics over the years was mixed with the fear of being treated as a war culprit by the occupying powers of the USA, Great Britain, France and the USSR in a similar way to 1918. A climate arose in which no one, neither those involved nor the following generation, spoke about what had happened. For a long time, this attitude prevented people from coming to terms with what had happened since 1933. The myth of Austria as the first victim of National Socialism, which only began to slowly crumble with the Waldheim affair in the 1980s, was born. Police officers, teachers, judges - they were all left in their jobs despite their political views. Society needed them to keep going.

An example of the generously spread cloak of oblivion with a strong connection to Innsbruck is the life of the doctor Burghard Breitner (1884-1956). Breitner grew up in a well-to-do middle-class household. The Villa Breitner at Mattsee was home to a museum about the German nationalist poet Josef Viktor Scheffel, who was honoured by his father. After graduating from high school, Breitner decided against a career in literature in favour of studying medicine. He then decided to do his military service and began his career as a doctor. In 1912/13 he served as a military doctor in the Balkan War. In 1914, he was sent to the Eastern Front, where he was taken prisoner of war by the Russians. As a doctor, he sacrificially cared for his comrades in the prison camp. It was not until 1920 that he was recognised as a hero and "Angel of Siberia" returned to Austria from the prison camp. In 1932, he began his career at the University of Innsbruck. In 1938, Breitner was faced with the problem that, due to his paternal grandmother's Jewish background, he had to take the "Great Aryan proof" could not provide. However, thanks to his good relationship with the Rector of Innsbruck University and important National Socialists, he was ultimately able to continue working at the university hospital. During the Nazi regime, Breitner was responsible for forced sterilisations and "Voluntary emasculation", even though he probably did not personally carry out any of the operations. After the war, the "Angel of Siberia" managed to wriggle through the denazification process with some difficulty. In 1951, he was nominated as a candidate for the VDUa political rallying point for staunch National Socialists, as a candidate for the federal presidential election. Breitner became Rector of the University of Innsbruck in 1952. After his death, the city of Innsbruck dedicated a grave of honour to him at Innsbruck West Cemetery. In Reichenau, a street is dedicated to him in the immediate vicinity of the site of the former concentration camp.

Art in architecture: the post-war period in Innsbruck

As after World War I, housing shortages were one of the most pressing problems after 1945. Innsbruck had suffered heavy damage during air raids, and money for new construction was scarce. When the first housing complexes were built in the 1950s, thrift was the order of the day. Many of the buildings erected from the 1950s onward may be architecturally unattractive, but they contain interesting artworks. From 1949 onward, Austria implemented the “Art in Architecture” project (Kunst am Bau). For state-funded construction projects, 2% of total expenditures were to be allocated to artistic design. The implementation of building regulations and thus the management of budgets was, as then and now, the responsibility of the federal states. Through these public commissions, artists were to be financially supported. In the lean post-war years, even successful and practically minded artists such as Oswald Haller (1908–1981), who earned money with commercial graphics and tourism posters, faced difficulties. The idea first appeared in 1919 in the Weimar Republic and was continued by the National Socialists from 1934 onward. Austria revived Kunst am Bau after the war to shape public spaces during reconstruction. The public sector, which replaced aristocracy and bourgeoisie as builders of previous centuries, was under massive financial pressure. Nevertheless, the primarily functional housing projects were not to appear entirely without ornamentation. Tyrolean artists entrusted with designing the artworks were selected through public competitions. The most famous among them was Max Weiler, perhaps the most prominent artist in post-war Tyrol, responsible for the frescoes in the Theresienkirche on the Hungerburg in Innsbruck. Other notable names include Helmut Rehm (1911–1991), Walter Honeder (1906–2006), Fritz Berger (1916–2002), and Emmerich Kerle (1916–2010). Many of these artists were shaped not only by the Federal Trade School in Innsbruck (today’s HTL) and the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna but also by the collective experience of National Socialism and the war. Fritz Berger had lost his right arm and an eye and had to learn to work with his left hand. Kerle served in Finland as a war painter and was taught at the Academy by Josef Müllner, an artist who entered art history with busts of Adolf Hitler, Siegfried from the Nibelungen saga, and the still controversial Karl Lueger monument in Vienna. Like much of the Tyrolean population, these artists—as well as politicians and officials—wanted peace and quiet after the harsh and painful war years, to let the grass grow over the events of the past decades. The works created under Kunst am Bau reflect this attitude toward a new moral order. It was the first time abstract, formless art entered Innsbruck’s public space, albeit only in an uncritical context. Fairy tales, legends, and religious symbols were popular motifs immortalized in sgraffitos, mosaics, murals, and statues. One could speak of a kind of second wave of Biedermeier art, symbolizing the petty-bourgeois lifestyle of people after the war. Art was also intended to create a new awareness and image of what was considered typically Austrian. As late as 1955, every second Austrian still regarded themselves as German. The various motifs depict leisure activities, clothing styles, and notions of social order and norms of the post-war era. Women were often shown in traditional dress and dirndls, men in lederhosen. Conservative ideals of gender roles were reflected in the art: hardworking fathers, dutiful wives caring for home and hearth, and children diligently learning at school were the ideal image well into the 1970s—a life like in a Peter Alexander film. Those who walk attentively through the city will find many of these still-visible artworks on houses in Pradl and Wilten. The mix of unremarkable architecture and contemporary artworks from the often-suppressed, long-idealized post-war era is worth seeing. Particularly beautiful examples can be found on façades in Pacherstraße, Hunoldstraße, Ing.-Thommenstraße, Innrain, at the Landesberufsschule Mandelsbergerstraße, or in the courtyard between Landhausplatz and Maria-Theresien-Straße.

The Red Bishop and Innsbruck's moral decay

In the 1950s, Innsbruck began to recover from the crisis and war years of the first half of the 20th century. On 15 May 1955, Federal Chancellor Leopold Figl declared with the famous words "Austria is free" and the signing of the State Treaty officially marked the political turning point. In many households, the "political turnaround" became established in the years known as Economic miracle moderate prosperity. Between 1953 and 1962, annual economic growth of over 6% allowed an increasing proportion of the population to dream of things that had long been exotic, such as refrigerators, their own bathroom or even a holiday in the south. This period brought not only material but also social change. People's desires became more outlandish with increasing prosperity and the lifestyle conveyed in advertising and the media. The phenomenon of a new youth culture began to spread gently amidst the grey society of small post-war Austria. The terms Teenager and "latchkey kid" entered the Austrian language in the 1950s. The big world came to Innsbruck via films. Cinema screenings and cinemas had already existed in Innsbruck at the turn of the century, but in the post-war period the programme was adapted to a young audience for the first time. Hardly anyone had a television set in their living room and the programme was meagre. The numerous cinemas courted the public's favour with scandalous films. From 1956, the magazine BRAVO. For the first time, there was a medium that was orientated towards the interests of young people. The first issue featured Marylin Monroe, with the question: „Marylin's curves also got married?“ The big stars of the early years were James Dean and Peter Kraus, before the Beatles took over in the 60s. After the Summer of Love Dr Sommer explained about love and sex. The church's omnipotent authority over the moral behaviour of adolescents began to crumble, albeit only slowly. The first photo love story with bare breasts did not follow until 1982. Until the 1970s, the opportunities for adolescent Innsbruckers were largely limited to pub parlours, shooting clubs and brass bands. Only gradually did bars, discos, nightclubs, pubs and event venues open. Events such as the 5 o'clock tea dance at the Sporthotel Igls attracted young people looking for a mate. The Cafe Central became the „second home of long-haired teenagers“, as the Tiroler Tageszeitung newspaper stated with horror in 1972. Establishments like the Falconry cellar in the Gilmstraße, the Uptown Jazzsalon in Hötting, the jazz club in the Hofgasse, the Clima Club in Saggen, the Scotch Club in the Angerzellgasse and the Tangent in Bruneckerstraße had nothing in common with the traditional Tyrolean beer and wine bar. The performances by the Rolling Stones and Deep Purple in the Olympic Hall in 1973 were the high point of Innsbruck's spring awakening for the time being. Innsbruck may not have become London or San Francisco, but it had at least breathed a breath of rock'n'roll. What is still anchored in cultural memory today as the '68 movement took place in the Holy Land hardly took place. Neither workers nor students took to the barricades in droves. The historian Fritz Keller described the „68 movement in Austria as "Mail fan“. Nevertheless, society was quietly and secretly changing. A look at the annual charts gives an indication of this. In 1964, it was still Chaplain Alfred Flury and Freddy with „Leave the little things“ and „Give me your word" and the Beatles with their German version of "Come, give me your hand who dominated the Top 10, musical tastes changed in the years leading up to the 1970s. Peter Alexander and Mireille Mathieu were still to be found in the charts. From 1967, however, it was international bands with foreign-language lyrics such as The Rolling Stones, Tom Jones, The Monkees, Scott McKenzie, Adriano Celentano or Simon and Garfunkel, who occupied the top positions in great density with partly socially critical lyrics.

This change provoked a backlash. The spearhead of the conservative counter-revolution was the Innsbruck bishop Paulus Rusch. Cigarettes, alcohol, overly permissive fashion, holidays abroad, working women, nightclubs, premarital sex, the 40-hour week, Sunday sporting events, dance evenings, mixed sexes in school and leisure - all of these things were strictly abhorrent to the strict churchman and follower of the Sacred Heart cult. Peter Paul Rusch was born in Munich in 1903 and grew up in Vorarlberg as the youngest of three children in a middle-class household. Both parents and his older sister died of tuberculosis before he reached adulthood. At the young age of 17, Rusch had to fend for himself early on in the meagre post-war period. Inflation had eaten up his father's inheritance, which could have financed his studies, in no time at all. Rusch worked for six years at the Bank for Tyrol and Vorarlberg, in order to finance his theological studies. He entered the Collegium Canisianum in 1927 and was ordained a priest of the Jesuit order six years later. His stellar career took the intelligent young man first to Lech and Hohenems as chaplain and then back to Innsbruck as head of the seminary. In 1938, he became titular bishop of Lykopolis and Apostolic Administrator for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. As the youngest bishop in Europe, he had to survive the harassment of the church by the National Socialist rulers. Although his critical attitude towards National Socialism was well known, Rusch himself was never imprisoned. Those in power were too afraid of turning the popular young bishop into a martyr.

After the war, the socially and politically committed bishop was at the forefront of reconstruction efforts. He wanted the church to have more influence on people's everyday lives again. His father had worked his way up from carpenter to architect and probably gave him a soft spot for the building industry. He also had his own experience at BTV. Thanks to his training as a banker, Rusch recognised the opportunities for the church to get involved and make a name for itself as a helper in times of need. It was not only the churches that had been damaged in the war that were rebuilt. The Catholic Youth under Rusch's leadership, was involved free of charge in the construction of the Heiligjahrsiedlung in the Höttinger Au. The diocese bought a building plot from the Ursuline order for this purpose. The loans for the settlers were advanced interest-free by the church. Decades later, his rustic approach to the housing issue would earn him the title of "Red Bishop" to the new home. In the modest little houses with self-catering gardens, in line with the ideas of the dogmatic and frugal "working-class bishop", 41 families, preferably with many children, found a new home.

By alleviating the housing shortage, the greatest threats in the Cold WarCommunism and socialism, from his community. The atheism prescribed by communism and the consumer-orientated capitalism that had swept into Western Europe from the USA after the war were anathema to him. In 1953, Rusch's book "Young worker, where to?". What sounds like revolutionary, left-wing reading from the Kremlin showed the principles of Christian social teaching, which castigated both capitalism and socialism. Families should live modestly in order to live in Christian harmony with the moderate financial means of a single father. Entrepreneurs, employees and workers were to form a peaceful unity. Co-operation instead of class warfare, the basis of today's social partnership. To each his own place in a Christian sense, a kind of modern feudal system that was already planned for use in Dollfuß's corporative state. He shared his political views with Governor Eduard Wallnöfer and Mayor Alois Lugger, who, together with the bishop, organised the Holy Trinity of conservative Tyrol at the time of the economic miracle. Rusch combined this with a latent Catholic anti-Semitism that was still widespread in Tyrol after 1945 and which, thanks to aberrations such as the veneration of the Anderle von Rinn has long been a tradition.

Education and training were of particular concern to the pugnacious Jesuit. The social formation across all classes by the soldiers of Christ could look back on a long tradition in Innsbruck. In 1909, the Jesuit priest and former prison chaplain Alois Mathiowitz (1853 - 1922) founded the Peter-Mayr-Bund. His approach was to put young people on the right path through leisure activities and sport and adults from working-class backgrounds through lectures and popular education. The workers' youth centre in Reichenauerstraße, which was built under his aegis, still serves as a youth centre and kindergarten today. Rusch also had experience with young people. In 1936, he was elected regional field master of the scouts in Vorarlberg. Despite a speech impediment, he was a charismatic guy and extremely popular with his young colleagues and teenagers. In his opinion, only a sound education under the wing of the church according to the Christian model could save the salvation of young people. In order to give young people a perspective and steer them in an orderly direction with a home and family, the Youth building society savings strengthened. In the parishes, kindergartens, youth centres and educational institutions such as the House of encounter on Rennweg in order to have education in the hands of the church right from the start. The vast majority of the social life of the city's young people did not take place in disreputable dive bars. Most young people simply didn't have the money to go out regularly. Many found their place in the more or less orderly channels of Catholic youth organisations. Alongside the ultra-conservative Bishop Rusch, a generation of liberal clerics grew up who became involved in youth work. In the 1960s and 70s, two church youth movements with great influence were active in Innsbruck. Sigmund Kripp and Meinrad Schumacher were responsible for this, who were able to win over teenagers and young adults with new approaches to education and a more open approach to sensitive topics such as sexuality and drugs. The education of the elite in the spirit of the Jesuit order was provided in Innsbruck from 1578 by the Marian Congregation. This youth organisation, still known today as the MK, took care of secondary school pupils. The MK had a strict hierarchical structure in order to give the young Soldaten Christi obedience from the very beginning. In 1959, Father Sigmund Kripp took over the leadership of the organisation. Under his leadership, the young people, with financial support from the church, state and parents and with a great deal of personal effort, set up projects such as the Mittergrathütte including its own material cable car in Kühtai and the legendary youth centre Kennedy House in the Sillgasse. Chancellor Klaus and members of the American embassy were present at the laying of the foundation stone for this youth centre, which was to become the largest of its kind in Europe with almost 1,500 members, as the building was dedicated to the first Catholic president of the USA, who had only recently been assassinated.

The other church youth organisation in Innsbruck was Z6. The city's youth chaplain, Chaplain Meinrad Schumacher, took care of the youth organisation as part of the Action 4-5-6 to all young people who are in the MK or the Catholic Student Union had no place. Working-class children and apprentices met in various youth centres such as Pradl or Reichenau before the new centre, also built by the members themselves, was opened at Zollerstraße 6 in 1971. Josef Windischer took over the management of the centre. The Z6 already had more to do with what Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda were doing on the big screen on their motorbikes in Easy Rider was shown. Things were rougher here than in the MK. Rock gangs like the Santanas, petty criminals and drug addicts also spent their free time in Z6. While Schumacher reeled off his programme upstairs with the "good" youngsters, Windischer and the Outsiders the basement to help the lost sheep as much as possible.

At the end of the 1960s, both the MK and the Z6 decided to open up to non-members. Girls' and boys' groups were partially merged and non-members were also admitted. Although the two youth centres had different target groups, the concept was the same. Theological knowledge and Christian morals were taught in a playful, age-appropriate environment. Sections such as chess, football, hockey, basketball, music, cinema films and a party room catered to the young people's needs for games, sport and the removal of taboos surrounding their first sexual experiences. The youth centres offered a space where young people of both sexes could meet. However, the MK in particular remained an institution that had nothing to do with the wild life of the '68ers, as it is often portrayed in films. For example, dance courses did not take place during Advent, carnival or on Saturdays, and for under-17s they were forbidden.

Nevertheless, the youth centres went too far for Bishop Rusch. The critical articles in the MK newspaper We discuss, which reached a circulation of over 2,000 copies, found less and less favour. Solidarity with Vietnam was one thing, but criticism of marksmen and the army could not be tolerated. After years of disputes between the bishop and the youth centre, it came to a showdown in 1973. When Father Kripp published his book Farewell to tomorrow in which he reported on his pedagogical concept and the work in the MK, there were non-public proceedings within the diocese and the Jesuit order against the director of the youth centre. Despite massive protests from parents and members, Kripp was removed. Neither the intervention within the church by the eminent theologian Karl Rahner, nor a petition initiated by the artist Paul Flora, nor regional and national outrage in the press could save the overly liberal Father from the wrath of Rusch, who even secured the papal blessing from Rome for his removal from office.

In July 1974, the Z6 was also temporarily over. Articles about the contraceptive pill and the Z6 newspaper's criticism of the Catholic Church were too much for the strict bishop. Rusch had the keys to the youth centre changed without further ado, a method he also used at the Catholic Student Union when it got too close to a left-wing action group. The Tiroler Tageszeitung noted this in a small article on 1 August 1974:

"In recent weeks, there had been profound disputes between the educators and the bishop over fundamental issues. According to the bishop, the views expressed in "Z 6" were "no longer in line with church teaching". For example, the leadership of the centre granted young people absolute freedom of conscience without simultaneously recognising objective norms and also permitted sexual relations before marriage."

It was his adherence to conservative values and his stubbornness that damaged Rusch's reputation in the last 20 years of his life. When he was consecrated as the first bishop of the newly founded diocese of Innsbruck in 1964, times were changing. The progressive with practical life experience of the past was overtaken by the modern life of a new generation and the needs of the emerging consumer society. The bishop's constant criticism of the lifestyle of his flock and his stubborn adherence to his overly conservative values, coupled with some bizarre statements, turned the co-founder of development aid into a Brother in needthe young, hands-on bishop of the reconstruction, from the late 1960s onwards as a reason for leaving the church. His concept of repentance and penance took on bizarre forms. He demanded guilt and atonement from the Tyroleans for their misdemeanours during the Nazi era, but at the same time described the denazification laws as too far-reaching and strict. In response to the new sexual practices and abortion laws under Chancellor Kreisky, he said that girls and young women who have premature sexual intercourse are up to twelve times more likely to develop cancer of the mother's organs. Rusch described Hamburg as a cesspool of sin and he suspected that the simple minds of the Tyrolean population were not up to phenomena such as tourism and nightclubs and were tempted to immoral behaviour. He feared that technology and progress were making people too independent of God. He was strictly against the new custom of double income. People should be satisfied with a spiritual family home with a vegetable garden and not strive for more; women should concentrate on their traditional role as housewife and mother.

In 1973, after 35 years at the head of the church community in Tyrol and Innsbruck, Bishop Rusch was made an honorary citizen of the city of Innsbruck. He resigned from his office in 1981. In 1986, Innsbruck's first bishop was laid to rest in St Jakob's Cathedral. The Bishop Paul's Student Residence The church of St Peter Canisius in the Höttinger Au, which was built under him, commemorates him.

After its closure in 1974, the Z6 youth centre moved to Andreas-Hofer-Straße 11 before finding its current home in Dreiheiligenstraße, in the middle of the working-class district of the early modern period opposite the Pest Church. Jussuf Windischer remained in Innsbruck after working on social projects in Brazil. The father of four children continued to work with socially marginalised groups, was a lecturer at the Social Academy, prison chaplain and director of the Caritas Integration House in Innsbruck.

The MK also still exists today, even though the Kennedy House, which was converted into a Sigmund Kripp House was renamed, no longer exists. In 2005, Kripp was made an honorary citizen of the city of Innsbruck by his former sodalist and later deputy mayor, like Bishop Rusch before him.

Innsbruck and National Socialism

In the 1920s and 30s, the NSDAP also grew and prospered in Tyrol. The first local branch of the NSDAP in Innsbruck was founded in 1923. With "Der Nationalsozialist - Combat Gazette for Tyrol and Vorarlberg“ published its own weekly newspaper. In 1933, the NSDAP also experienced a meteoric rise in Innsbruck with the tailwind from Germany. The general dissatisfaction and disenchantment with politics among the citizens and theatrically staged torchlight processions through the city, including swastika-shaped bonfires on the Nordkette mountain range during the election campaign, helped the party to make huge gains. Over 1800 Innsbruck residents were members of the SA, which had its headquarters at Bürgerstraße 10. While the National Socialists were only able to win 2.8% of the vote in their first municipal council election in 1921, this figure had already risen to 41% by the 1933 elections. Nine mandataries, including the later mayor Egon Denz and the Gauleiter of Tyrol Franz Hofer, were elected to the municipal council. It was not only Hitler's election as Reich Chancellor in Germany, but also campaigns and manifestations in Innsbruck that helped the party, which had been banned in Austria since 1934, to achieve this result. As everywhere else, it was mainly young people in Innsbruck who were enthusiastic about National Socialism. They were attracted by the new, the clearing away of old hierarchies and structures such as the Catholic Church, the upheaval and the unprecedented style. National Socialism was particularly popular among the big German-minded lads of the student fraternities and often also among professors.

When the annexation of Austria to Germany took place in March 1938, civil war-like scenes ensued. Already in the run-up to the invasion, there had been repeated marches and rallies by the National Socialists after the ban on the party had been lifted. Even before Federal Chancellor Schuschnigg gave his last speech to the people before handing over power to the National Socialists with the words "God bless Austria" had closed on 11 March 1938, the National Socialists were already gathering in the city centre to celebrate the invasion of the German troops. The police of the corporative state were partly sympathetic to the riots of the organised manifestations and partly powerless in the face of the goings-on. Although the Landhaus and Maria-Theresien-Straße were cordoned off and secured with machine-gun posts, there was no question of any crackdown by the executive. "One people - one empire - one leader" echoed through the city. The threat of the German military and the deployment of SA troops dispelled the last doubts. More and more of the enthusiastic population joined in. At the Tiroler Landhaus, then still in Maria-Theresienstraße, and at the provisional headquarters of the National Socialists in the Gasthaus Old Innspruggthe swastika flag was hoisted.

On 12 March, the people of Innsbruck gave the German military a frenetic welcome. To ensure hospitality towards the National Socialists, Mayor Egon Denz had each worker paid a week's wages. On 5 April, Adolf Hitler personally visited Innsbruck to be celebrated by the crowd. Archive photos show a euphoric crowd awaiting the Führer, the promise of salvation. Mountain fires in the shape of swastikas were lit on the Nordkette. The referendum on 10 April resulted in a vote of over 99% in favour of Austria's annexation to Germany. After the economic hardship of the interwar period, the economic crisis and the governments under Dollfuß and Schuschnigg, people were tired and wanted change. What kind of change was initially less important than the change itself. "Showing them up there", that was Hitler's promise. The Wehrmacht and industry offered young people a perspective, even those who had little to do with the ideology of National Socialism in and of itself. The fact that there were repeated outbreaks of violence was not unusual for the interwar period in Austria anyway. Unlike today, democracy was not something that anyone could have got used to in the short period between the monarchy in 1918 and the elimination of parliament under Dollfuß in 1933, which was characterised by political extremes. There is no need to abolish something that does not actually exist in the minds of the population.

Tyrol and Vorarlberg were combined into a Reichsgau with Innsbruck as its capital. Even though National Socialism was viewed sceptically by a large part of the population, there was hardly any organised or even armed resistance, as the Catholic resistance OE5 and the left in Tyrol were not strong enough for this. There were isolated instances of unorganised subversive behaviour by the population, especially in the arch-Catholic rural communities around Innsbruck. The power apparatus dominated people's everyday lives too comprehensively. Many jobs and other comforts of life were tied to an at least outwardly loyal attitude to the party. The majority of the population was spared imprisonment, but the fear of it was omnipresent.

The regime under Hofer and Gestapo chief Werner Hilliges also did a great job of suppression. In Tyrol, the church was the biggest obstacle. During National Socialism, the Catholic Church was systematically combated. Catholic schools were converted, youth organisations and associations were banned, monasteries were closed, religious education was abolished and a church tax was introduced. Particularly stubborn priests such as Otto Neururer were sent to concentration camps. Local politicians such as the later Innsbruck mayors Anton Melzer and Franz Greiter also had to flee or were arrested. It would go beyond the scope of this article to summarise the violence and crimes committed against the Jewish population, the clergy, political suspects, civilians and prisoners of war. The Gestapo headquarters were located at Herrengasse 1, where suspects were severely abused and sometimes beaten to death with fists. In 1941, the Reichenau labour camp was set up in Rossau near the Innsbruck building yard. Suspects of all kinds were kept here for forced labour in shabby barracks. Over 130 people died in this camp consisting of 20 barracks due to illness, the poor conditions, labour accidents or executions. Prisoners were also forced to work at the Messerschmitt factory in the village of Kematen, 10 kilometres from Innsbruck. These included political prisoners, Russian prisoners of war and Jews. The forced labour included, among other things, the construction of the South Tyrolean settlements in the final phase or the tunnels to protect against air raids in the south of Innsbruck. In the Innsbruck clinic, disabled people and those deemed unacceptable by the system, such as homosexuals, were forcibly sterilised.

The memorials to the National Socialist era are few and far between. The Tiroler Landhaus with the Liberation Monument and the building of the Old University are the two most striking memorials. The forecourt of the university and a small column at the southern entrance to the hospital were also designed to commemorate what was probably the darkest chapter in Austria's history.