Hungerburg

Worth knowing

Looking up from Innsbruck toward the Nordkette, one notices a striking structure: a yellow, somewhat bulky-looking cube situated on the plateau nearly 300 meters above the city. Today, hikers, mountain bikers, and tourists gather there to enjoy majestic views of the surrounding peaks and to wait for the cable car taking them to the Seegrube and the Hafelekar. In the early 20th century, however, this area was home to a kind of artificial wonderland for affluent travelers as well as an exclusive planned community. What Dubai accomplished in the 21st century with its fantastical tourism project The Palm had already been attempted on Innsbruck’s Hungerburg more than a century earlier—indeed, the history of its creation reaches back even further. The journey from the no‑man’s‑land between the formerly independent municipalities of Hötting and Mühlau to a popular tourist hotspot was a long one. For centuries, the area stretching from Gramartboden in the west across the quarry below it to Mühlau in the east was largely undeveloped forestland. The steep, pale rock formations gave the region the field name Grauenstein (“grey rock”). In 1840, after clearing some of the forest, Joseph von Attlmayr—owner of Weiherburg Castle—purchased significant portions of land on the plateau overlooking the city. A shrewd businessman, Attlmayr was already operating part of his residence as a lodging establishment. According to legend, while standing above the quarry and looking across the valley toward Heiligwasser, he struck the ground with his walking stick. When water emerged from the soil, he decided to dedicate the site to the Virgin Mary and the miraculous water. He piously named the farmstead he built there Mariabrunn. Attlmayr leased the building as an inn, laying the foundation for the Hungerburg’s rise as a beloved holiday and excursion destination. Another legend claims that the food served there was so poor that locals mockingly called the place Hungerburg (“Hunger Fortress”), but the name actually predates the inn’s opening.

In the second half of the 19th century, tourism became an important economic sector in Innsbruck. The Hungerburg—blessed with its supposedly health‑giving air at over 800 meters above sea level and its panoramic view—had great potential, but with no accessible road, it could only be reached on foot. Wealthy travelers of the era arrived with heavy luggage and stayed for weeks. It took a visionary pioneer to unlock the area’s potential, and this figure was the Kaiserjäger officer Sebastian Kandler (1863–1928). Before becoming an early tourism entrepreneur, Kandler had led an eventful career. He joined the military at 18 and later worked in the canteen of the Klosterkaserne. In 1902, he built what is now Villa St. Georg in the Saggen district and opened the restaurant Klaudia. After just a year, he sold it and purchased the Mariabrunn estate from Attlmayr’s descendants. Kandler didn’t just see the Hungerburg’s potential—he actively developed it. He expanded the Hotel Mariabrunn in an exotic mixture of architectural styles, giving it the appearance of a small castle. Under his direction, more hotels were built: Villa Karwendel, Villa Felsen, and Villa Kandlerheim. Since the construction of villas and cottage-style homes had been banned in the Saggen since 1898, the new trendy hillside district attracted wealthy citizens seeking their dream of an exclusive single-family residence. To make the Hungerburg appealing to visitors, Kandler also created infrastructure. He transformed the steep path from Weiherburg—once climbed by Emperor Ferdinand in 1848—into the safe, easily accessible Wilhelm‑Greil promenade. The Café Bahnhof at the Hungerburgbahn mountain station, the Karwendelhof, and the Waldschenke provided refreshments. The crowning achievement of his efforts was the opening of the Hungerburg Railway in 1906. Starting at the Kettenbrücke in Saggen, the spectacular line connected the city to the upscale hillside district. From downtown, one could now ascend effortlessly to the plateau—spending several weeks as a wealthy tourist or a few hours as a day‑trip visitor, elevated physically and socially above the city.

The second major investor in Hoch‑Innsbruck was Franz Schwärzler, who had acquired one of the exclusive villas on the Hungerburg. A dynamic businessman, he didn’t stop at hotels or his Tyrolean Specialty House, where visitors could purchase Tyrolean arts, crafts, and local products as souvenirs. In 1911, he developed the idea of creating an artificial lake in the former Spörr quarry. Together with his brother, he began the ambitious project in February 1912. Above the 3,500 m² lake, they constructed a medieval-style tower with a viewing terrace and a rocky promenade. On August 4, Mayor Wilhelm Greil and the imperial‑royal governor of Tyrol, Markus Freiherr von Spiegelfeld, officially opened the attraction. In summer, swimmers and would-be captains in rowboats filled the lake; in winter, it became an ice-skating rink. Its banks featured not only an artificial cave—heightening the Alpine romanticism—but also the Hotel Hungerburgseehof. At its beachfront tables, aristocrats from the old world and the nouveau riche of the international jet set drank fine wines and champagne. Although the remote Hungerburg hosted only a handful of homes and hotels, a gendarmerie post was established to protect its affluent residents and visitors. With the outbreak of World War I, the exclusive spectacle came to an abrupt halt. Like many who had invested in luxury ventures or war bonds, Kandler and Schwärzler lost their fortunes. Schwärzler’s widow was forced to sell the Seehof, which later served the Social Democratic Party, the Fatherland Front, and eventually—under National Socialism—as an elementary school. Kandler sold his Hotel Mariabrunn to an industrialist from Vorarlberg. His final years resembled his youth: he spent his days in the Halleranger, desperately searching for silver.

The Hungerburg received new momentum with the construction of the Höhenstraße mountain road. As the economy recovered in the mid‑1920s and major projects resumed, the long‑planned road connection—independent of the Hungerburgbahn—was finally realized. Builder Fritz Konzert had already proposed a route in 1906, while Schwärzler, at the height of his imaginative endeavors, had also envisioned a road in 1911. The Höhenstraße, winding from Hötting Church through what is now a densely developed area and up to the Hungerburg in several switchbacks over 3.5 km, opened in 1930 after a little more than a year of construction under Viktor Berger. Not only was the Hungerburg now linked to Innsbruck by road; with the incorporation of Hötting and Mühlau in 1938, it officially became part of the city. The district emblem near the cableway, the Gasthaus zur Linde, and the Seehof commemorates the Hungerburg’s origins, combining the old Hötting church tower, Mühlau’s millwheel, and the pillars of the original Hungerburgbahn in the Inn River at Saggen.

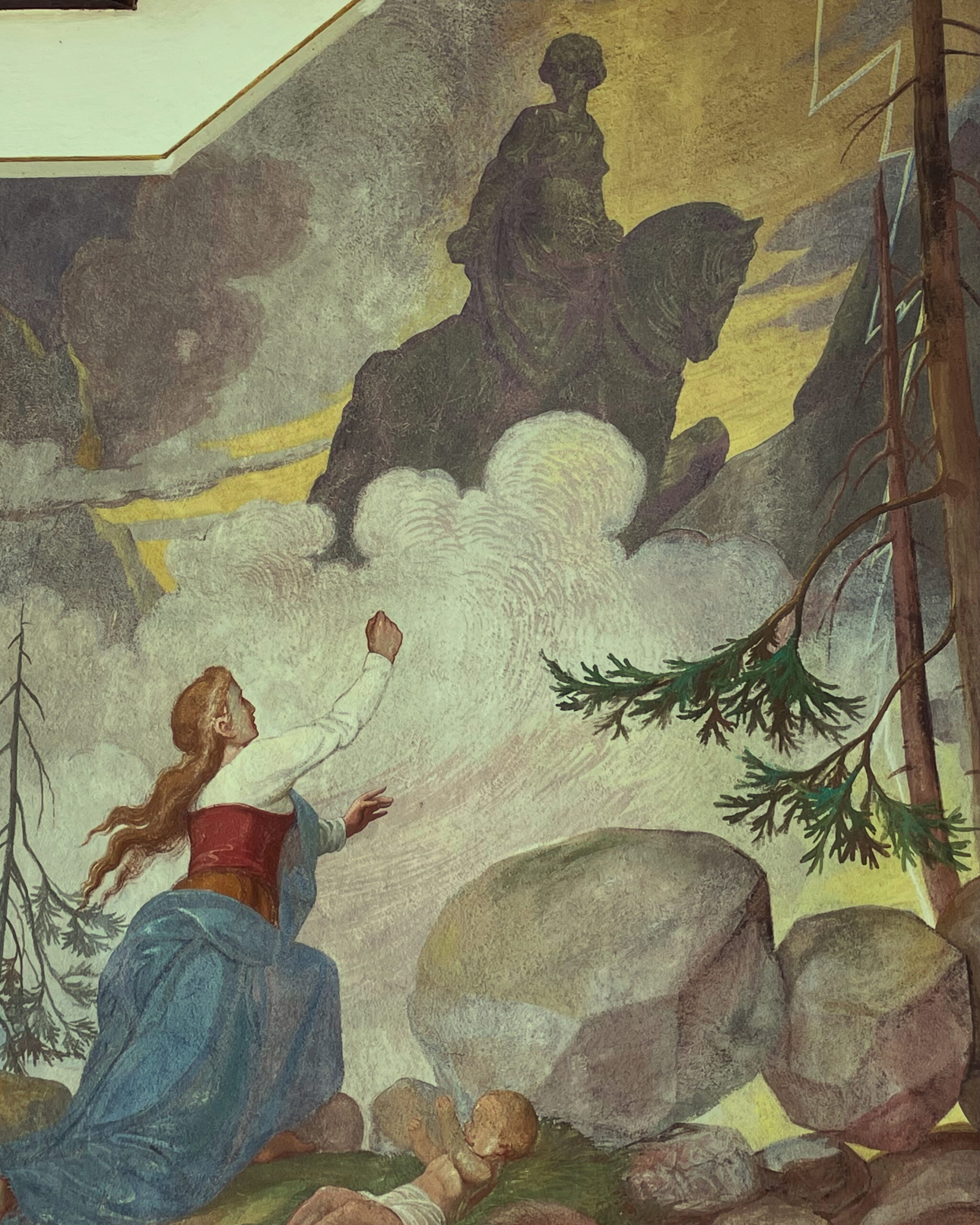

But what exactly is the striking yellow building that catches every eye from the valley? It is the former Hotel Mariabrunn, built by Kandler. In 1930, parts of the late‑historicist building burned down, and its new owner commissioned young rising star architect Siegfried Mazagg to redesign it completely. The cubic, asymmetrical elements recall contemporary works of New Objectivity architecture, such as the municipal indoor pool. In 1988, brothers Hubert and Michael Prachensky redesigned the interior into residential flats while preserving Mazagg’s exterior. The inscription Mariabrunn is still clearly visible on its western side. Today, the futuristic mountain station of the Hungerburgbahn—designed by Iranian architect Zaha Hadid—dominates the district. The square in front of it, overlooking the Inn Valley and surrounding mountains, is named after Innsbruck mountaineer Hermann Buhl (1924–1957). Little remains of the turn-of-the-century fantasyland envisioned by Kandler and Schwärzler during the optimistic Belle Époque. The observation tower still rises above the now-dry former lake; the former Hotel Seehof houses offices of the Chamber of Labour. Despite heavy postwar development, several buildings from the early 1900s have survived. The villa beside the Theresienkirche, with its patriotic red-and-white shutters, resembles the Ottoburg in the Old Town. The façade of Gasthaus zur Linde—once Villa Tiroler Haus and part of Schwärzler’s empire—still features the legend of Frau Hitt, recalling the days when a kind of Tyrolean Disneyland flourished on the Hungerburg. Perhaps it is fitting that this tale of hubris and impermanence is the story that survived in Hoch‑Innsbruck. Today, the remarkable building in late‑monarchy Tyrolean Heimatstil houses a kindergarten. And the two pioneering tourism entrepreneurs, Kandler and Schwärzler, were ultimately right: the Nordkette is a hotspot. The crowded buses, funiculars, and gondolas carrying thousands of sightseers, hikers, skiers, and bikers to Hoch‑Innsbruck every day prove it.

Tourism: From Alpine summer retreat to Piefke Saga

In the 1990s, an Austrian television series caused a scandal. The Piefke Saga written by the Tyrolean author Felix Mitterer, describes the relationship between the German holidaymaker family Sattmann and their hosts in a fictitious Tyrolean holiday resort in four bizarrely amusing episodes. Despite all the scepticism about tourism in its current, sometimes extreme, excesses, it should not be forgotten that tourism was an important factor in Innsbruck and the surrounding area in the 19th century, driving the region's development in the long term, and not just economically.

The first travellers to Innsbruck were pilgrims and business people. Traders, journeymen on the road, civil servants, soldiers, entourages of aristocratic guests at court, skilled workers from various trades, miners, clerics, pilgrims and scientists were the first tourists to be drawn to the city between Italy and Germany. Travelling was expensive, dangerous and arduous. In addition, a large proportion of the subjects were not allowed to leave their own land without the permission of their landlord or abbot. Those who travelled usually did so on the cobbler's pony. Although Innsbruck's inns and innkeepers were already earning money from travellers in the Middle Ages and early modern times, there was no question of tourism as we understand it today. It began when a few crazy travellers were drawn to the mountain peaks for the first time. In addition to a growing middle class, this also required a new attitude towards the Alps. For a long time, the mountains had been a pure threat to people. It was mainly the British who set out to conquer the world's mountains after the oceans. From the late 18th century, the era of Romanticism, news of the natural beauty of the Alps spread through travelogues. The first foreign-language travel guide to Tyrol, Travells through the Rhaetian Alps by Jean Francois Beaumont was published in 1796.

In addition to the alpine attraction, it was the wild and exotic Natives Tirols, die international für Aufsehen sorgten. Der bärtige Revoluzzer namens Andreas Hofer, der es mit seinem Bauernheer geschafft hatte, Napoleons Armee in die Knie zu zwingen, erzeugte bei den Briten, den notorischen Erzfeinden der Franzosen, ebenso großes Interesse wie bei deutschen Nationalisten nördlich der Alpen, die in ihm einen frühen Protodeutschen sahen. Die Tiroler galten als unbeugsamer Menschenschlag, archetypisch und ungezähmt, ähnlich den Germanen unter Arminius, die das Imperium Romanum herausgefordert hatten. Die Beschreibungen Innsbrucks aus der Feder des Autors Beda Weber (1798 – 1858) und andere Reiseberichte in der boomenden Presselandschaft dieser Zeit trugen dazu bei, ein attraktives Bild Innsbrucks zu prägen.

Nun mussten die wilden Alpen nur noch der Masse an Touristen zugänglich gemacht werden, die zwar gerne den frühen Abenteurern auf ihren Expeditionen nacheifern wollten, deren Risikobereitschaft und Fitness mit den Wünschen nicht schritthalten konnten. Der German Alpine Club eröffnete 1869 eine Sektion Innsbruck, nachdem der 1862 Österreichische Alpenverein was not very successful. Driven by the Greater German idea of many members, the two institutions merged in 1873. Alpine Club is still bourgeois to this day, while its social democratic counterpart is the Naturfreunde. The network of paths grew as a result of its development, as did the number of huts that could accommodate guests. The transit country of Tyrol had countless mule tracks and footpaths that had existed for centuries and served as the basis for alpinism. Small inns, farms and stations along the postal routes served as accommodation. The Tyrolean theologian Franz Senn (1831 - 1884) and the writer Adolf Pichler (1819 - 1900) were instrumental in the surveying of Tyrol and the creation of maps. Contrary to popular belief, the Tyroleans were not born mountaineers, but had to be taught the skills to conquer the mountains. Until then, mountains had been one thing above all: dangerous and arduous in everyday agricultural life. Climbing them had hardly occurred to anyone before. The Alpine clubs also trained mountain guides. From the turn of the century, skiing came into fashion alongside hiking and mountaineering. There were no lifts yet, and to get up the mountains you had to use the skins that are still glued to touring skis today. It was not until the 1920s, following the construction of the cable cars on the Nordkette and Patscherkofel mountains, that a wealthy clientele was able to enjoy the modern luxury of mountain lifts while skiing.

New hotels, cafés, inns, shops and means of transport were needed to meet the needs of guests. Anyone who had running water and a telephone connection at home in London or Paris did not want to make do with an outhouse in the corridor or in front of the house when on holiday. The so-called first and second class inns were suitable for transit traffic, but they were not equipped to receive upscale tourists. Until the 19th century, innkeepers in the city and in the villages around Innsbruck belonged to the upper middle class in terms of income. They were often farmers who ran a pub on the side and sold food. As the example of Andreas Hofer shows, they also had a good reputation and influence within local society. As meeting places for the locals and hubs for postal and goods traffic, they were often well informed about what was happening in the wider world. However, as they were neither members of a guild nor counted among the middle classes, the profession of innkeeper was not one of the most honourable professions. This changed with the professionalisation of the tourism industry. Entrepreneurs such as Robert Nißl, who took over Büchsenhausen Castle in 1865 and converted it into a brewery, invested in the infrastructure. Former aristocratic residences such as Weiherburg Castle became inns and hotels. The revolution in Innsbruck did not take place on the barricades in 1848, but in tourism a few decades later, when resourceful citizens replaced the aristocracy as owners of castles such as Büchsenhausen and Weiherburg.

Opened in 1849, the Österreichischer Hof was long regarded as the top dog of the modern hotel industry, but was officially just a copy of a grand hotel. Only with the Grand Hotel Europa had opened a first-class establishment in Innsbruck in 1869. The heyday of the inns in the old town was over. In 1892, the zeitgeisty Reformhotel Habsburger Hof a second large business. Where the Metropolkino cinema stands today, the Kaiserhof was built as a new building. The Habsburg Court already offered its guests electric light, an absolute sensation. Also on the previously unused area in front of the railway station was the Arlberger Hof settled. What would be seen as a competitive disadvantage today was a selling point at the time. Railway stations were the centres of modern cities. Station squares were not overcrowded transport hubs as they are today, but sophisticated and well-kept places in front of the architecturally sophisticated halls where the trains arrived.

The number of guests increased slowly but steadily. Shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, Innsbruck had 200,000 guests. In June 1896, the Innsbrucker Nachrichten:

„Der Fremdenverkehr in Innsbruck bezifferte sich im Monat Mai auf 5647 Personen. Darunter befanden sich (außer 2763 Reisenden aus Oesterreich-Ungarn) 1974 Reichsdeutsche, 282 Engländer, 65 Italiener, 68 Franzosen, 53 Amerikaner, 51 Russen und 388 Personen aus verschiedenen anderen Ländern.“

In addition to the number of travellers who had an impact on life in the small town of Innsbruck, it was also the internationality of the visitors who gradually gave Innsbruck a new look. In addition to the purely touristic infrastructure, the development of general innovations was also accelerated. The wealthy guests could hardly socialise in pubs with cesspits behind their houses. Of course, a sewerage system would have been on the agenda anyway, but the economic factor of tourism made it possible and accelerated the release of funds for the major projects at the turn of the century. This not only changed the appearance of the town, but also people's everyday and working lives. Resourceful entrepreneurs such as Heinrich Menardi managed to expand the value chain to include paid holiday pleasures in addition to board and lodging. In 1880, he opened the Lohnkutscherei und Autovermietung Heinrich Menardi for excursions in the Alpine surroundings. Initially with carriages, and after the First World War with coaches and cars, wealthy tourists were chauffeured as far as Venice. The company still exists today and is now based in the Menardihaus at Wilhelm-Greil-Strasse 17 opposite Landhausplatz, even though over time the transport and trading industry shifted to the more lucrative property sector. Local trade also benefited from the wealthy clientele from abroad. In 1909, there were already three dedicated Tourist equipment shops next to the fashionable department stores that had just opened a few years earlier.

Innsbruck and the surrounding towns were also known for spa holidays, the predecessor of today's wellness, where well-heeled clients recovered from a wide variety of illnesses in an Alpine environment. The Igler Hof, back then Grandhotel Igler Hof and the Sporthotel Igls, still partly exude the chic of that time. Michael Obexer, the founder of the spa town of Igls and owner of the Grand Hotel, was a tourism pioneer. There were two spas in Egerdach near Amras and in Mühlau. The facilities were not as well-known as the hotspots of the time in Bad Ischl, Marienbad or Baden near Vienna, as can be seen on old photos and postcards, but the treatments with brine, steam, gymnastics and even magnetism were in line with the standards of the time, some of which are still popular with spa and wellness holidaymakers today. Bad Egerdach near Innsbruck had been known as a healing spring since the 17th century. The spring was said to cure gout, skin diseases, anaemia and even the nervous disorder known in the 19th century as neurasthenia, the predecessor of burnout. The institution's chapel still exists today opposite the SOS Children's Village. The bathing establishment in Mühlau has existed since 1768 and was converted into an inn and spa in the style of the time in the course of the 19th century. The former bathing establishment is now a residential building worth seeing in Anton-Rauch-Straße. However, the most spectacular tourist project that Innsbruck ever experienced was probably Hoch Innsbruck, today's Hungerburg. Not only the Hungerburg railway and hotels, but even its own lake was created here after the turn of the century to attract guests.

One of the former owners of the land of the Hungerburg and Innsbruck tourism pioneer, Richard von Attlmayr, was significantly involved in the predecessor of today's tourism association. Since 1881, the Innsbruck Beautification Association to satisfy the increasing needs of guests. The association took care of the construction of hiking and walking trails, the installation of benches and the development of impassable areas such as the Mühlauer Klamm or the Sillschlucht gorge. The striking green benches along many paths are a reminder of the still existing association. 1888 years later, the profiteers of tourism in Innsbruck founded the Commission for the promotion of tourismthe predecessor of today's tourism association. By joining forces in advertising and quality assurance at the accommodation establishments, the individual businesses hoped to further boost tourism.

„Alljährlich mehrt sich die Zahl der überseeischen Pilger, die unser Land und dessen gletscherbekrönte Berge zum Verdrusse unserer freundnachbarlichen Schweizer besuchen und manch klingenden Dollar zurücklassen. Die Engländer fangen an Tirol ebenso interessant zu finden wie die Schweiz, die Zahl der Franzosen und Niederländer, die den Sommer bei uns zubringen, mehrt sich von Jahr zu Jahr.“

Postkarten waren die ersten massentauglichen Influencer der Tourismusgeschichte. Viele Betriebe ließen ihre eigenen Postkarten drucken. Verlage produzierten unzählige Sujets der beliebtesten Sehenswürdigkeiten der Stadt. Es ist interessant zu sehen, was damals als sehenswert galt und auf den Karten abgebildet wurde. Anders als heute waren es vor allem die zeitgenössisch modernen Errungenschaften der Stadt: der Leopoldbrunnen, das Stadtcafé beim Theater, die Kettenbrücke, die Zahnradbahn auf die Hungerburg oder die 1845 eröffnete Stefansbrücke an der Brennerstraße, die als Steinbogen aus Quadern die Sill überquerte, waren die Attraktionen. Auch Andreas Hofer war ein gut funktionierendes Testimonial auf den Postkarten: Der Gasthof Schupfen in dem Andreas Hofer sein Hauptquartier hatte und der Berg Isel mit dem großen Andreas-Hofer-Denkmal waren gerne abgebildete Motive.

1914 gab es in Innsbruck 17 Hotels, die Gäste anlockten. Dazu kamen die Sommer- und Winterfrischler in Igls und dem Stubaital. Der Erste Weltkrieg ließ die erste touristische Welle mit einem Streich versanden. Gerade als sich der Fremdenverkehr Ende der 1920er Jahre langsam wieder erholt hatte, kamen mit der Wirtschaftskrise und Hitlers 1000 Mark blockThe next setback came in 1933, when he tried to put pressure on the Austrian government to end the ban on the NSDAP.

It required the Economic miracle in the 1950s and 1960s to revitalise tourism in Innsbruck after the destruction. Between 1955 and 1972, the number of overnight stays in Tyrol increased fivefold. After the arduous war years and the reconstruction of the European economy, Tyrol and Innsbruck were able to slowly but steadily establish tourism as a stable source of income, even away from the official hotels and guesthouses. Many Innsbruck families moved together in their already cramped flats to supplement their household budgets by renting out beds to guests from abroad. Tourism not only brought in foreign currency, but also enabled the locals to create a new image of themselves both internally and externally. At the same time, the economic upturn made it possible for more and more Innsbruck residents to go on holiday abroad. The beaches of Italy were particularly popular. The wartime enemies of previous decades became guests and hosts.

A republic is born

Few eras are more difficult to grasp than the interwar period. The Roaring TwentiesJazz and automobiles come to mind, as do inflation and the economic crisis. In big cities like Berlin, young ladies behaved as Flappers mit Bubikopf, Zigarette und kurzen Röcken zu den neuen Klängen lasziv, Innsbrucks Bevölkerung gehörte als Teil der jungen Republik Österreich zum größten Teil zur Fraktion Armut, Wirtschaftskrise und politischer Polarisierung. Schon die Ausrufung der Republik am Parlament in Wien vor über 100.000 mehr oder minder begeisterten, vor allem aber verunsicherten Menschen verlief mit Tumulten, Schießereien, zwei Toten und 40 Verletzten alles andere als reibungsfrei. Wie es nach dem Ende der Monarchie und dem Wegfall eines großen Teils des Staatsterritoriums weitergehen sollte, wusste niemand. Das neue Österreich erschien zu klein und nicht lebensfähig. Der Beamtenstaat des k.u.k. Reiches setzte sich nahtlos unter neuer Fahne und Namen durch. Die Bundesländer als Nachfolger der alten Kronländer erhielten in der Verfassung im Rahmen des Föderalismus viel Spielraum in Gesetzgebung und Verwaltung. Die Begeisterung für den neuen Staat hielt sich aber in der Bevölkerung in Grenzen. Nicht nur, dass die Versorgungslage nach dem Wegfall des allergrößten Teils des ehemaligen Riesenreiches der Habsburger miserabel war, die Menschen misstrauten dem Grundgedanken der Republik. Die Monarchie war nicht perfekt gewesen, mit dem Gedanken von Demokratie konnten aber nur die allerwenigsten etwas anfangen. Anstatt Untertan des Kaisers war man nun zwar Bürger, allerdings nur Bürger eines Zwergstaates mit überdimensionierter und in den Bundesländern wenig geliebter Hauptstadt anstatt eines großen Reiches. In den ehemaligen Kronländern, die zum großen Teil christlich-sozial regiert wurden, sprach man gerne vom Viennese water headwho was fed by the yields of the industrious rural population.

Other federal states also toyed with the idea of seceding from the Republic after the plan to join Germany, which was supported by all parties, was prohibited by the victorious powers of the First World War. The Tyrolean plans, however, were particularly spectacular. From a neutral Alpine state with other federal states, a free state consisting of Tyrol and Bavaria or from Kufstein to Salurn, an annexation to Switzerland and even a Catholic church state under papal leadership, there were many ideas. The most obvious solution was particularly popular. In Tyrol, feeling German was nothing new. So why not align oneself politically with the big brother in the north? This desire was particularly pronounced among urban elites and students. The annexation to Germany was approved by 98% in a vote in Tyrol, but never materialised.

Instead of becoming part of Germany, they were subject to the unloved Wallschen. Italian troops occupied Innsbruck for almost two years after the end of the war. At the peace negotiations in Paris, the Brenner Pass was declared the new border. The historic Tyrol was divided in two. The military was stationed at the Brenner Pass to secure a border that had never existed before and was perceived as unnatural and unjust. In 1924, the Innsbruck municipal council decided to name squares and streets around the main railway station after South Tyrolean towns. Bozner Platz, Brixnerstrasse and Salurnerstrasse still bear their names today. Many people on both sides of the Brenner felt betrayed. Although the war was far from won, they did not see themselves as losers to Italy. Hatred of Italians reached its peak in the interwar period, even if the occupying troops were emphatically lenient. A passage from the short story collection "The front above the peaks" by the National Socialist author Karl Springenschmid from the 1930s reflects the general mood:

"The young girl says, 'Becoming Italian would be the worst thing.

Old Tappeiner just nods and grumbles: "I know it myself and we all know it: becoming a whale would be the worst thing."

Trouble also loomed in domestic politics. The revolution in Russia and the ensuing civil war with millions of deaths, expropriation and a complete reversal of the system cast its long shadow all the way to Austria. The prospect of Soviet conditions machte den Menschen Angst. Österreich war tief gespalten. Hauptstadt und Bundesländer, Stadt und Land, Bürger, Arbeiter und Bauern – im Vakuum der ersten Nachkriegsjahre wollte jede Gruppe die Zukunft nach ihren Vorstellungen gestalten. Die Kulturkämpfe der späten Monarchie zwischen Konservativen, Liberalen und Sozialisten setzte sich nahtlos fort. Die Kluft bestand nicht nur auf politischer Ebene. Moral, Familie, Freizeitgestaltung, Erziehung, Glaube, Rechtsverständnis – jeder Lebensbereich war betroffen. Wer sollte regieren? Wie sollten Vermögen, Rechte und Pflichten verteilt werden. Ein kommunistischer Umsturz war besonders in Tirol keine reale Gefahr, ließ sich aber medial gut als Bedrohung instrumentalisieren, um die Sozialdemokratie in Verruf zu bringen. 1919 hatte sich in Innsbruck zwar ein Workers', farmers' and soldiers' council nach sowjetischem Vorbild ausgerufen, sein Einfluss blieb aber gering und wurde von keiner Partei unterstützt. Ab 1920 bildeten sich offiziell sogenannten Soldatenräte, die aber christlich-sozial dominiert waren. Das bäuerliche und bürgerliche Lager rechts der Mitte militarisierte sich mit der Tiroler Heimatwehr professioneller und konnte sich über stärkeren Zulauf freuen als linke Gruppen, auch dank kirchlicher Unterstützung. Die Sozialdemokratie wurde von den Kirchkanzeln herab und in konservativen Medien als Jewish Party and homeless traitors to their country. They were all too readily blamed for the lost war and its consequences. The Tiroler Anzeiger summarised the people's fears in a nutshell: "Woe to the Christian people if the Jews=Socialists win the elections!".

With the new municipal council regulations of 1919, which provided for universal suffrage for all adults, the Innsbruck municipal council comprised 40 members. Of the 24,644 citizens called to the ballot box, an incredible 24,060 exercised their right to vote. Three women were already represented in the first municipal council with free elections. While in the rural districts the Tyrolean People's Party as a merger of Farmers' Union, People's Association und Catholic Labour Despite the strong headwinds in Innsbruck, the Social Democrats under the leadership of Martin Rapoldi were always able to win between 30 and 50% of the vote in the first elections in 1919. The fact that the Social Democrats did not succeed in winning the mayor's seat was due to the majorities in the municipal council formed by alliances with other parties. Liberals and Tyrolean People's Party was at least as hostile to social democracy as he was to the federal capital Vienna and the Italian occupiers.

But high politics was only the framework of the actual misery. The as Spanish flu This epidemic, which has gone down in history, also took its toll in Innsbruck in the years following the war. Exact figures were not recorded, but the number of deaths worldwide is estimated at 27 - 50 million. In Innsbruck, at the height of the Spanish flu epidemic, it is estimated that around 100 people fell victim to the disease every day. Many Innsbruck residents had not returned home from the battlefields and were missing as fathers, husbands and labourers. Many of those who had made it back were wounded and scarred by the horrors of war. As late as February 1920, the „Tyrolean Committee of the Siberians" im Gasthof Breinößl "...in favour of the fund for the repatriation of our prisoners of war..." organised a charity evening. Long after the war, the province of Tyrol still needed help from abroad to feed the population. Under the heading "Significant expansion of the American children's aid programme in Tyrol" was published on 9 April 1921 in the Innsbrucker Nachrichten to read: "Taking into account the needs of the province of Tyrol, the American representatives for Austria have most generously increased the daily number of meals to 18,000 portions.“

Then there was unemployment. Civil servants and public sector employees in particular lost their jobs after the League of Nations linked its loan to severe austerity measures. Salaries in the public sector were cut. There were repeated strikes. Tourism as an economic factor was non-existent due to the problems in the neighbouring countries, which were also shaken by the war. The construction industry, which had been booming before the war, collapsed completely. Innsbruck's largest company Huter & Söhne hatte 1913 über 700 Mitarbeiter, am Höhepunkt der Wirtschaftskrise 1933 waren es nur noch 18. Der Mittelstand brach zu einem guten Teil zusammen. Der durchschnittliche Innsbrucker war mittellos und mangelernährt. Oft konnten nicht mehr als 800 Kalorien pro Tag zusammengekratzt werden. Die Kriminalitätsrate war in diesem Klima der Armut höher als je zuvor. Viele Menschen verloren ihre Bleibe. 1922 waren in Innsbruck 3000 Familien auf Wohnungssuche trotz eines städtischen Notwohnungsprogrammes, das bereits mehrere Jahre in Kraft war. In alle verfügbaren Objekte wurden Wohnungen gebaut. Am 11. Februar 1921 fand sich in einer langen Liste in den Innsbrucker Nachrichten on the individual projects that were run, including this item:

„The municipal hospital abandoned the epidemic barracks in Pradl and made them available to the municipality for the construction of emergency flats. The necessary loan of 295 K (note: crowns) was approved for the construction of 7 emergency flats.“

Very little happened in the first few years. Then politics awoke from its lethargy. The crown, a relic from the monarchy, was replaced by the schilling as Austria's official currency on 1 January 1925. The old currency had lost more than 95% of its value against the dollar between 1918 and 1922, or the pre-war exchange rate. Innsbruck, like many other Austrian municipalities, began to print its own money. The amount of money in circulation rose from 12 billion crowns to over 3 trillion crowns between 1920 and 1922. The result was an epochal inflation.

With the currency reorganisation following the League of Nations loan under Chancellor Ignaz Seipel, not only banks and citizens picked themselves up, but public building contracts also increased again. Innsbruck modernised itself. There was what economists call a false boom. This short-lived economic recovery was a Bubble, However, the city of Innsbruck was awarded major projects such as the Tivoli, the municipal indoor swimming pool, the high road to the Hungerburg, the mountain railways to the Isel and the Nordkette, new schools and apartment blocks. The town bought Lake Achensee and, as the main shareholder of TIWAG, built the power station in Jenbach. The first airport was built in Reichenau in 1925, which also involved Innsbruck in air traffic 65 years after the opening of the railway line. In 1930, the university bridge connected the hospital in Wilten and the Höttinger Au. The Pembaur Bridge and the Prince Eugene Bridge were built on the River Sill. The signature of the new, large mass parties in the design of these projects cannot be overlooked.

The first republic was a difficult birth from the remnants of the former monarchy and it was not to last long. Despite the post-war problems, however, a lot of positive things also happened in the First Republic. Subjects became citizens. What began in the time of Maria Theresa was now continued under new auspices. The change from subject to citizen was characterised not only by a new right to vote, but above all by the increased care of the state. State regulations, schools, kindergartens, labour offices, hospitals and municipal housing estates replaced the benevolence of the landlord, sovereigns, wealthy citizens, the monarchy and the church.

To this day, much of the Austrian state and Innsbruck's cityscape and infrastructure are based on what emerged after the collapse of the monarchy. In Innsbruck, there are no conscious memorials to the emergence of the First Republic in Austria. The listed residential complexes such as the Slaughterhouse blockthe Pembaurblock or the Mandelsbergerblock oder die Pembaur School are contemporary witnesses turned to stone. Every year since 1925, World Savings Day has commemorated the introduction of the schilling. Children and adults should be educated to handle money responsibly.

Franz Baumann and Tyrolean modernism

The First World War not only brought ruling dynasties and empires to an end, the 1920s also saw many changes in art, music, literature and architecture. While jazz, atonal music and expressionism failed to establish themselves in little Innsbruck, a handful of architects changed the cityscape in an astonishing way. Inspired by new forms of design such as the Bauhaus style, skyscrapers from the USA and the Soviet Modernism from the revolutionary USSR, sensational projects emerged in Innsbruck. The best-known representatives of the avant-garde who brought about this new way of designing public space in Tyrol were Lois Welzenbacher, Siegfried Mazagg, Theodor Prachensky and Clemens Holzmeister. Each of these architects had their own idiosyncrasies, making the Tiroler Moderne nur schwer eindeutig zu definieren ist. Allen gemeinsam war die Abwendung von der klassizistischen Architektur der Vorkriegszeit unter gleichzeitiger Beibehaltung typischer alpiner Materialien und Elemente unter dem Motto Form follows function. Lois Welzenbacher schrieb 1920 in einem Artikel der Zeitschrift Tyrolean highlands about the architecture of this period:

"As far as we can judge today, it is clear that the 19th century lacked the strength to create its own distinct style. It is the age of stillness... Thus details were reproduced with historical accuracy, mostly without any particular meaning or purpose, and without a harmonious overall picture that would have arisen from factual or artistic necessity."

The best-known and most impressive representative of the so-called Tiroler Moderne was Franz Baumann (1892 - 1974). Unlike Holzmeister or Welzenbacher, he had no academic training. Baumann was born in Innsbruck in 1892, the son of a postal clerk. The theologian, publicist and war propagandist Anton Müllner, alias Bruder Willram became aware of Franz Baumann's talent as a draughtsman and enabled the young man to attend the Staatsgewerbeschule, today's HTL, at the age of 14. It was here that he met his future brother-in-law Theodor Prachensky. Together with Baumann's sister Maria, the two young men went on excursions in the area around Innsbruck to paint pictures of the mountains and nature. During his school years, he gained his first professional experience as a bricklayer at the construction company Huter & Söhne. In 1910 Baumann followed his friend Prachensky to Merano to work for the company Musch & Lun zu arbeiten. Meran war damals Tirols wichtigster Tourismusort mit internationalen Kurgästen. Unter dem Architekten Adalbert Erlebach machte er erste Erfahrungen bei der Planung von Großprojekten wie Hotels und Seilbahnen. Wie den Großteil seiner Generation riss der Erste Weltkrieg auch Baumann aus Berufsleben und Alltag. An der Italienfront erlitt er im Kampfeinsatz einen Bauchschuss, von dem er sich in einem Lazarett in Prag erholte. In dieser ansonsten tatenlosen Zeit malte er Stadtansichten von Bauwerken in und rund um Prag. Diese Bilder, die ihm später bei der Visualisierung seiner Pläne helfen sollten, wurden in seiner einzigen Ausstellung 1919 präsentiert.

Baumann's breakthrough came in the second half of the 1920s. He was able to win the tenders for the remodelling of the Weinhaus Happ in the old town and the Nordkettenbahn railway. In addition to his creativity and ability to think holistically, he was also able to harmonise his architectural approach with the legal situation and the modern requirements of tendering in the 1920s. Construction was a state matter, the Tyrolean Heritage Protection Association together with the district administration, was the final authority responsible for the assessment and authorisation of construction projects. During his time in Merano, Baumann was already involved with the Homeland Security Association came into contact with it. Kunibert Zimmeter had founded this association together with Gotthard Graf Trapp in the final years of the monarchy. In "Our Tyrol. A heritage book" he wrote:

"Let us look at the flattening of our private lives, our amusements, at the centre of which, significantly, is the cinema, at the literary ephemera of our newspaper reading, at the hopeless and costly excesses of fashion in the field of women's clothing, let us take a look at our homes with the miserable factory furniture and all the dreadful products of our so-called gallantry goods industry, Things that thousands of people work to produce, creating worthless bric-a-brac in the process, or let us look at our apartment blocks and villas with their cement façades simulating palaces, countless superfluous towers and gables, our hotels with their pompous façades, what a waste of the people's wealth, what an abundance of tastelessness we must find there."

The economic boom of the late 1920s saw the emergence of a new clientele and clientele that placed new demands on buildings and therefore on the construction industry. In many Tyrolean villages, hotels had replaced churches as the largest building in the townscape. The aristocratic distance from the mountains had given way to a bourgeois enthusiasm for sport. This called for new solutions at new heights. No more grand hotels were built at 1500 m for spa holidays, but a complete infrastructure for skiers in high alpine terrain such as the Nordkette. The Tyrolean Heritage Protection Association ensured that nature and townscape were protected from overly fashionable trends, excessive tourism and ugly industrial buildings. Building projects had to blend harmoniously, attractively and appropriately into the environment. Despite the social and artistic innovations of the time, architects had to keep the typical regional character in mind. This was precisely the strength of Baumann's approach to holistic building in the Tyrolean sense. All technical functions and details, the embedding of the buildings in the landscape, taking into account the topography and sunlight, played a role for him, who was not officially allowed to use the title of architect. He thus followed the "Rules for those who build in the mountains" by the architect Adolf Loos from 1913:

Don't build picturesquely. Leave such effects to the walls, the mountains and the sun. The man who dresses picturesquely is not picturesque, but a buffoon. The farmer does not dress picturesquely. But he is...

Pay attention to the forms in which the farmer builds. For they are ancestral wisdom, congealed substance. But seek out the reason for the mould. If advances in technology have made it possible to improve the mould, then this improvement should always be used. The flail will be replaced by the threshing machine."

Baumann designed even the smallest details, from the exterior lighting to the furniture, and integrated them into his overall concept of the Tiroler Moderne in.

From 1927, Baumann worked independently in his studio in Schöpfstraße in Wilten. He repeatedly came into contact with his brother-in-law and employee of the building authority, Theodor Prachensky. From 1929, the two of them worked together to design the building for the new Hötting secondary school on Fürstenweg. Although boys and girls still had to be planned separately in the traditional way, the building was otherwise completely in keeping with the style of the Neuen Sachlichkeit and the principle Light, air and sun.

In his heyday, he employed 14 people in his office. Thanks to his modern approach, which combined function, aesthetics and economical construction, he survived the economic crisis well. Only the 1000-mark barrier, die Hitler 1934 über Österreich verhängte, um die Republik finanziell in Bredouille zu bringen, brachte sein Architekturbüro wie die gesamte Wirtschaft in Probleme. Nicht nur die Arbeitslosenquote im Tourismus verdreifachte sich innerhalb kürzester Zeit, auch die Baubranche geriet in Schwierigkeiten. 1935 wurde Baumann zum Leiter der Zentralvereinigung für Architekten, nachdem er mit einer Ausnahmegenehmigung ausgestattet diesen Berufstitel endlich tragen durfte. Im gleichen Jahr plante er die Hörtnaglsiedlung in the west of the city.

After the Anschluss in 1938, he quickly joined the NSDAP. On the one hand, like his colleague Lois Welzenbacher, he was probably not averse to the ideas of National Socialism, but on the other he was able to further his career as chairman of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts in Tyrol. In this position, he courageously opposed the destructive furore with which those in power wanted to change Innsbruck's cityscape, which did not correspond to his idea of urban planning. The mayor of Innsbruck, Egon Denz, wanted to remove the Triumphal Gate and St Anne's Column in order to make more room for traffic in Maria-Theresienstraße. The city centre was still a transit area from the Brenner Pass in the south to reach the main road to the east and west on today's Innrain. At the request of Gauleiter Franz Hofer, a statue of Adolf Hitler was to be erected in place of St Anne's Column. Hofer also wanted to have the church towers of the collegiate church blown up. Baumann's opinion on these plans was negative. When the matter made it to Albert Speer's desk, he agreed with him. From this point onwards, Baumann was no longer awarded any public projects by Gauleiter Hofer.

After being questioned as part of the denazification process, Baumann began working at the city building authority, probably on the recommendation of his brother-in-law Prachensky. Baumann was fully exonerated, among other things by a statement from the Abbot of Wilten, whose church towers he had saved, but his reputation as an architect could no longer be repaired. Moreover, his studio in Schöpfstraße had been destroyed by a bomb in 1944. In his post-war career, he was responsible for the renovation of buildings damaged by the war. Under his leadership, Boznerplatz with the Rudolfsbrunnen fountain was rebuilt as well as Burggraben and the new Stadtsäle (Note: today House of Music).

Franz Baumann died in 1974 and his paintings, sketches and drawings are highly sought-after and highly traded. Anyone who takes a close look at recent major projects such as the city library, the PEMA towers and many of Innsbruck's housing estates will recognise the approaches of the Tiroler Moderne rediscover even today.