Leopoldstraße & Wiltener Platzl

Leopoldstrasse

Worth knowing

The Wiltener Platzltoday a popular meeting place for Innsbruck's youth and students, has its roots, if you like, in Roman antiquity. On the corner of Leopoldstraße and Dr.-Karl-von-Grabmayr-Straße, a mural from the 1950s commemorates the Roman military camp of Veldidena. It was located directly on the driveway to the Via Raetia Today it is bordered by the Sill to the east, the Südring to the north and Stafflerstraße to the west. Four mighty watchtowers and a wall over 2 metres thick surrounded the castle, where more than 500 soldiers were stationed. A trading post, a village with a tavern, armourers, brickworks and craftsmen's workshops grew up around the military camp. The land around Veldidena had to be cleared for the livestock. Equipment and clothing had to be made and repaired, and the men had to be fed and entertained.

The village of Wilten around the monastery with its centre at today's Haymon Inn grew towards the town of Innsbruck even after the Bavarian takeover of the Inn Valley. A lively village life developed outside the enclosure of the monastery. Wiltein According to the monastery's land register, it consisted of the large Meierhof, 2 mills, 12 farms, 5 fiefs, 30 small cottages and a Preuhauswhere the beer for the cheerful monastery life was produced. Long before Innsbruck's main traffic artery, the Südring, mercilessly cut through the city centre from the 1960s onwards, a kind of medieval Bacon belt. In the 19th century, Wilten became the centre of the Little Sill the fastest growing part of today's city of Innsbruck.

On Lower village square A second village centre was already established in the Middle Ages. At the beginning of the 17th century, the village had 80 houses and an impressive 600 inhabitants. By 1775, Wilten had grown to the present-day Leopoldstraße 22. 56 town houses and 80 farms, plus five inns and seven aristocratic residences were home to around 1000 people. While in the monastery and the Leuthaus the administration of the village, the parishes and lands of the monastery were based here, where today Wiltener Platzl und Kaiserschützenplatz The city's economic and civil life was centred around the Brenner Pass. Traders and travellers moved from the Brenner Road to Innsbruck to pay their toll at the customs station at the Triumphal Gate. Over time, the farmhouses that had settled around the village fountain developed into bourgeois residences, aristocratic residences, craft businesses and shops along this main thoroughfare. The variety of architectural styles still bears witness to the lively hustle and bustle over the centuries.

The house at Leopoldstraße 27 was home to a blacksmith from 1428 at the latest. Together with house number 25, it is a marvellous example of residential buildings from the first half of the 19th century and Biedermeier architecture. Not only did the economically barren period after the Napoleonic Wars cause a lull in the construction industry, many of the less attractive buildings of this period were swept away by the furore of historicism after 1880. The core of the building opposite at Leopoldstraße 30 and 32 can even be traced back to the 12th century. Where today there is a fashion boutique and flats, merchants were able to sell their goods in the Materialists Ladele and thus reduce the expected load at the customs station. The magnificent manor house at Leopoldstraße 22 is known as the Steidlevilla known. The core of the building dates back to the 17th century, but in the 19th century it was transformed from an aristocratic residence into a neoclassical villa in the style of the bourgeois building frenzy. It was named after the Tyrolean home defence leader Richard Steidle, who was shot and seriously wounded by German National Socialists Werner von Alversleben in front of his villa in 1933.

The square building at today's Liebeneggstraße 2, decorated with Baroque paintings, developed together with the Welsbergschlössl at Leopoldstraße 35 in the 15th century from a farmhouse to a Liebenegg residence. In 1601, the two houses were confirmed as an open-air residence, which also included a farmhouse with a meadow. In 1824, the k.k. Gubernial registrar had the Liebenegg residence to four storeys and convert it into a block of flats.

A little further towards the city centre is one of Innsbruck's most traditional inns. In 1901, Heinrich and Maria Steneck from Trentino opened the Wine restaurant Steneck. The pub was particularly popular with the Italian-speaking population of Innsbruck. Both the Italian Prime Minister Alcide de Gasperi as a young student and Benito Mussolini are said to have enjoyed specialities and wine from their homeland here during their time in Innsbruck. The people of Innsbruck were fond of the Wallschen for a long time, the exceptionally good catering was nevertheless gladly accepted. Generations of Innsbruckers have enjoyed the Stennias the now ageing pub is affectionately known, enjoyed schnitzel, sausages and chips at affordable prices. When Heinrich Steneck passed away on 22 December 1953, Innsbrucker Nachrichten bid a touching farewell to the founder of this institution on behalf of the entire city.

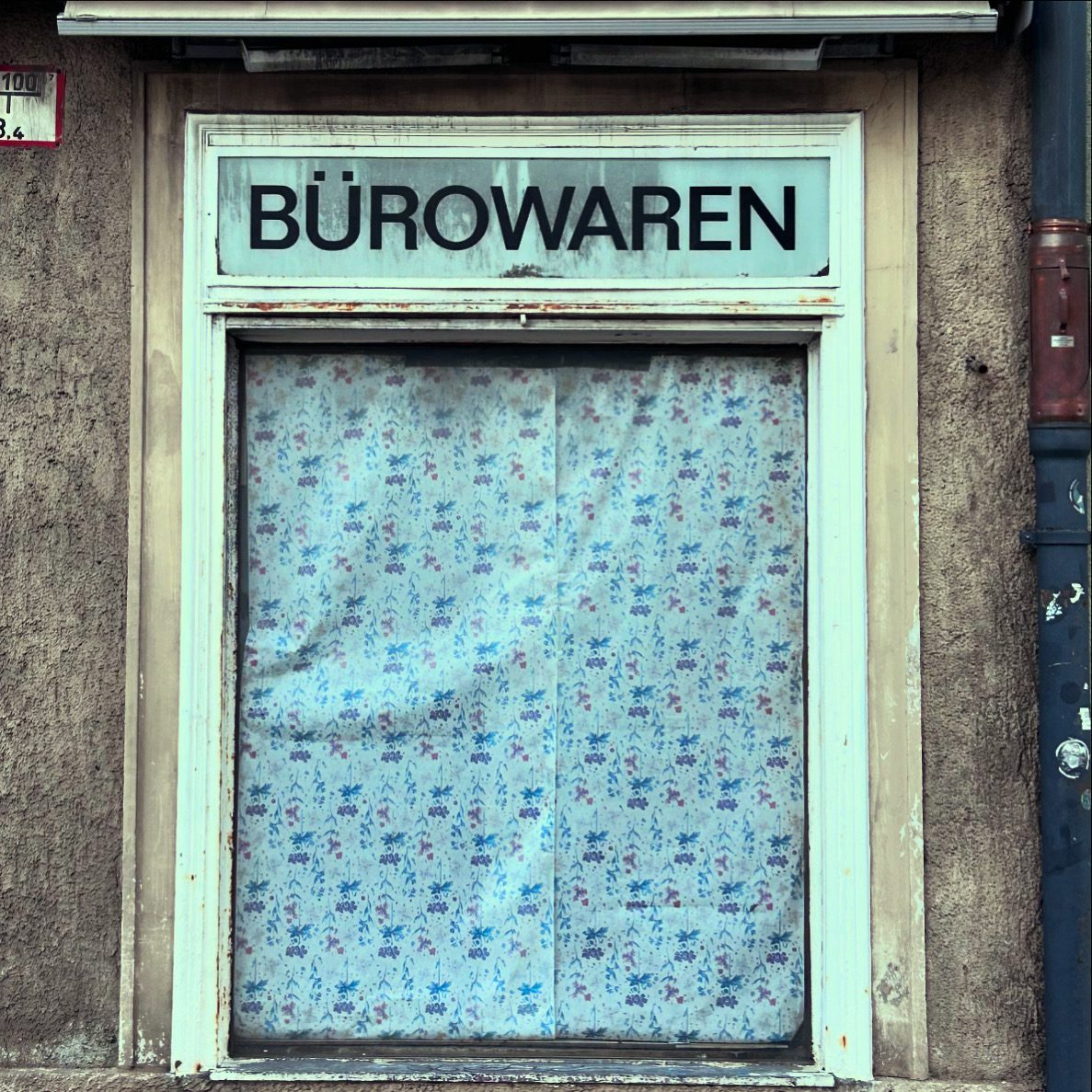

The increase in traffic since the 1980s took away the charm of the former village centre. Only with the recent redesign of the Wiltener Platzls has succeeded in making this historic square more attractive again. The modern village square with its fountain and seating area is a popular meeting place for residents and walkers alike. Between the two buildings of Ansitz Liebenegg is the modern building in which the Wilten neighbourhood meeting place, a service provided by the Innsbruck Social Services is housed here. The Leopoldstrasse and the Leopoldstraße continue their tradition as a commercial centre outside the city centre. Wiltener Platzl continues to this day. Unlike other main streets in the peripheral neighbourhoods, shops of all kinds flourish here. Boutiques, studios and other small shops manage to establish themselves in the latest hip neighbourhood. Grätzel as well as long-established and new eateries on Wiltener Platzl. The weekly market and a small Christmas market in Advent also enliven the urban zone.

Innsbruck as part of the Imperium Romanum

Of course, the Inn Valley was not first colonised with the Roman conquest. The inhabitants of the Alps, described as wild, predatory and barbaric, were labelled by Greek and Roman writers with the rather vague collective term „Raeter“ dubbed. These people probably did not refer to themselves as such. Today, researchers use the term Raeter to refer to the inhabitants of Tyrol, the lower Engadin and Trentino, the area of the Fritzens-Sanzeno Culturenamed after their major archaeological sites. Two-storey houses with stone foundations grouped in clustered villages, similar language idioms, burnt offering sites such as the Goldbühel in Igls and pottery finds indicate a common cultural background and economic exchange between the ethnic groups and organisations between Vorarlberg, Lake Garda and Istria. According to finds, there was also a lively exchange with other ethnic groups such as the Celts in the west or the Etruscans in the south even before the Roman conquests. Etruscan characters were used for all kinds of records.

According to Roman interpretation, the Breons, a tribe within the Raetians, lived in the area of today's Innsbruck. This name persisted even after the fall of the Roman Empire until the Bavarian colonisation in the 9th century. Although there were no Breon Popular Frontthe quote from Life of Brian could also have been used in pre-Christian Innsbruck:

"Apart from medicine, sanitation, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, water treatment and public health insurance, what, I ask you, have the Romans ever done for us?"

A climatic phenomenon known as Roman climate optimum the area north of the Alps for the first time in history. Roman Empire interesting and accessible via the Alpine crossings. From a strategic point of view, the conquest was overdue anyway. The Roman troops in Gaul in the west and Illyria on the Adriatic in the east were to be connected, invasions by barbarian peoples into northern Italian settlements were to be prevented and routes for trade, travellers and the military were to be expanded and secured. The Inn Valley, an important corridor for troop movements, communication and trade on the outer edge of the Roman economic area, had to be brought under Roman control. The transport route between today's Seefeld Saddle and the Brenner Pass already existed before the Roman conquest, but was not a paved, modern road that met the demands of Roman requirements.

In the year 15 BC, the generals Tiberius and Drusus, both stepsons of Emperor Augustus, conquered the area that is now Innsbruck. Drusus marched from Verona to Trento and then along the Adige River over the Brenner Pass to the area that is now Innsbruck. There, the Roman troops fought against the local Breons. The Roman administration was rolled out under Augustus' successor Tiberius. The military was followed by the administration. Today's Tyrol was divided at the river Ziller. The area east of the Ziller became part of the province of Noricum, Innsbruck hingegen wurde ein Teil der Provinz Raetia et Vindelicia. It stretched from today's central Switzerland with the Gotthard massif in the west to the Alpine foothills north of Lake Constance, the Brenner in the south and the Ziller in the east. The Ziller has remained a border in the division of Tyrol in terms of church law to this day. The area east of the Ziller belongs to the diocese of Salzburg, while Tyrol west of the Ziller belongs to the diocese of Innsbruck.

It is unclear whether the Romans destroyed the settlements and places of worship between Zirl and Wattens during their campaign of conquest. The burnt offering site at Goldbühel in Igls was no longer used after the year 15. There are also no precise sources on the treatment of the conquered people. The settlements of the Breon population were located on the higher scree cones such as Amras and Wilten and above the Inn Valley, which was a marshy area. The Romans settled in the area of today's Wilten Abbey. The Roman troops most likely drew on the expertise of the local population to secure and construct the transport routes. Today we would probably say that important human resources were handled with care after the takeover.

The soon Via Raetia named road made the Via Claudia Augustawhich linked Italy and Bavaria via the Reschen Pass and Fern Pass, as the most important transport route across the Alps. In the 3rd century after the turn of the millennium, the Brenner route became the via publica developed. It was too steep in parts for poorly equipped trade trains to become the main route, but traffic increased noticeably and with it the importance of the Wipp and Inn valleys. Just over five metres wide, it ran from the Brenner Pass to the Ferrariwiese meadow above Wilten over the Isel mountain to today's Gasthaus Haymon. At intervals of 20 to 40 kilometres there were rest stations with accommodation, restaurants and stables. In Sterzing, on the Brenner Pass, in Matrei and Innsbruck, these Roman Mansiones Villages where Roman culture began to establish itself.

The settlement and later the military camp were connected via this road network. Castell Veldidena was integrated into an economic and intellectual area stretching from Great Britain to the Baltic and North Africa. The population began to adapt to the conditions as a transit and supply station. Blacksmiths were the first steps in an early metalworking industry and inns were also founded. The Romans brought many of their cultural achievements such as imperial coinage, glass and brick production, the Latin language, bathhouses, thermal baths, schools and wine across the Brenner Pass. Roman law and administration were also introduced. Military service in the Roman army enabled people to climb the social ladder. With an imperial decree in 212, the Breton subjects became full Roman citizens with all the associated rights and duties. After Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century, the Tyrolean region was also proselytised. The episcopal administration was based in Brixen in South Tyrol and Trento.

There is hardly anything left of Roman Innsbruck in the cityscape. Exhibits can be admired in the Tyrolean State Museum Ferdinandeum. In various excavation projects, burial sites and remains such as walls, coins, bricks and everyday objects from the Roman period in Innsbruck were found around today's Wilten Abbey. The centre of the Leuthauses next to the monastery dates back to Roman times. One of the Roman milestones of the former main road over the Brenner Pass can be seen in Wiesengasse near the Tivoli Stadium.

Innsbruck's industrial revolutions

Im 15. Jahrhundert begann sich in Innsbruck eine erste frühe Form der Industrialisierung zu entwickeln. Die Metallverarbeitung florierte unter der aufsteigenden Bauwirtschaft in der boomenden Residenzstadt und der Herstellung von Waffen und Rüstungen. Viele Faktoren trafen dafür zusammen. Die verkehrsgünstige Lage der Stadt, die Verfügbarkeit von Wasserkraft, Innsbrucks politischer Aufstieg, das Knowhow der Handwerker und die Verfügbarkeit von Kapital unter Maximilian ermöglichten den Aufbau von Infrastruktur. Glocken- und Waffengießer wie die Löfflers errichteten in Hötting, Mühlau und Dreiheiligen Betriebe, die zu den führenden Werken Europas ihrer Zeit gehörten. Entlang des Sillkanals nutzten Mühlen und Betriebe die Wasserkraft zur Energiegewinnung. Pulverstampfer und Silberschmelzen hatten sich in der Silbergasse, der heutigen Universitätsstraße, angesiedelt. In der heutigen Adamgasse gab es eine Munitionsfabrik, die 1636 explodierte.

Metalworking also boosted other sectors of the economy. At the beginning of the 17th century, there were 270 businesses in Innsbruck, employing master craftsmen, journeymen and apprentices. Although the majority of Innsbruckers were still employed in administration, trade, crafts and the money that could be earned from them attracted a new class of people. There was a reshuffling within the city. Citizens and businesses were pushed out of the new town by the civil service and the nobility. Most of the baroque palazzi that adorn Maria-Theresienstraße today were built in the 17th century, while Dreiheiligen and St. Nikolaus became Innsbruck's industrial and working-class districts. In addition to the metalworking industry around Silbergasse, tanners, carpenters, wainwrights, master builders, stonemasons and other craftsmen of early industrialisation also settled here.

Industry not only changed the rules of the social game with the influx of new workers and their families, it also had an impact on the appearance of Innsbruck. Unlike the farmers, the labourers were not the subjects of any master. Although entrepreneurs were not of noble blood, they often had more capital at their disposal than the aristocracy. The old hierarchies still existed, but were beginning to become at least somewhat fragile. The new citizens brought with them new fashions and dressed differently. Capital from outside came into the city. Houses and churches were built for the newly arrived subjects. The large workshops changed the smell and sound of the city. The smelting works were loud, the smoke from the furnaces polluted the air. Innsbruck had gone from being a small settlement on the Inn bridge to a proto-industrial town.

Growth was slowed for several decades at the end of the 18th century by the Napoleonic Wars. The second wave of industrialisation came late in Innsbruck compared to other European regions. One reason for this was the late establishment of a functioning banking system in the city. Catholics still regarded bankers as „usurers and borrower“ and doing business with money was considered indecent. Without financing, however, even large enterprises could not be founded. In 1715, the Tyrolean provincial government had issued the so-called Banko gegründet und in der Herzog-Friedrich-Straße gab es die Privatbank Bederunger, erst mit der Gründung der ersten Filiale der Sparkasse wurde es möglich, sein Geld nicht mehr unter dem Kopfpolster zu verwahren. Nach 1850 begann man Kredite zu vergeben, was die Gründung heimischer größerer Betriebe ermöglichte. Das Small craftThe town's former craft businesses, which were organised in guilds, came under pressure from the achievements of modern goods production. In St. Nikolaus, Wilten, Mühlau and Pradl, modern factories were built along the Mühlbach stream and the Sill Canal. Many innovative company founders came from outside Innsbruck. Peter Walde, who moved to Innsbruck from Lusatia, founded his company in 1777 in what is now Innstrasse 23, producing products made from fat, such as tallow candles and soaps. Eight generations later, Walde is still one of the oldest family businesses in Austria. Today you can buy the result of centuries of tradition in soap and candle form in the listed main building with its Gothic vaults. Franz Josef Adam came from the Vinschgau Valley to found the city's largest brewery to date in a former aristocratic residence. In 1838, the spinning machine arrived via the Dornbirn company Herrburger & Rhomberg over the Arlberg to Pradl. H&R had acquired a plot of land on the Sillgründe. Thanks to the river's water power, the site was ideal for the heavy machinery used in the textile industry. In addition to the traditional sheep's wool, cotton was now also processed.

Just like 400 years earlier, the Second Industrial Revolution changed the city and the everyday lives of its inhabitants forever. Neighbourhoods such as Mühlau, Pradl and Wilten grew rapidly. The factories were often located in the centre of residential areas. Over 20 businesses were still using the Sill Canal around 1900. The Haidmühle The power plant in Salurnerstraße existed from 1315 to 1907 and supplied a textile factory in Dreiheiligenstraße with energy from the Sill Canal. The noise and exhaust fumes from the engines were hell for the neighbours, as a newspaper article from 1912 shows:

„Entrüstung ruft bei den Bewohnern des nächst dem Hauptbahnhofe gelegenen Stadtteiles der seit einiger Zeit in der hibler´schen Feigenkaffeefabrik aufgestellte Explosionsmotor hervor. Der Lärm, welchen diese Maschine fast den ganzen Tag ununterbrochen verbreitet, stört die ganz Umgebung in der empfindlichsten Weise und muß die umliegenden Wohnungen entwerten. In den am Bahnhofplatze liegenden Hotels sind die früher so gesuchten und beliebten Gartenzimmer kaum mehr zu vermieten. Noch schlimmer als der ruhestörende Lärm aber ist der Qualm und Gestank der neuen Maschine…“

Aristokraten, die sich zu lange auf ihrem Geburtsverdienst auf der faulen Haut ausruhten, während sich die wirtschaftlichen und gesellschaftlichen Spielregeln änderten, mussten ihre Anwesen an den neuen Geldadel verkaufen. Im Palais Sarnthein gegenüber der Triumphpforte, 1689 von Johann Anton Gumpp für David Graf Sarnthein noch als barocker Ansitz geplant, zog die Waffenfabrik und das Geschäft von Johann Peterlongo ein. Geschickte Mitglieder des Adelsstandes nutzten ihre Voraussetzungen und investierten Familienbesitz und Erträge aus der bäuerlichen Grundentlastung von 1848 in Industrie und Wirtschaft. Der steigende Arbeitskräftebedarf wurde von ehemaligen Knechten und Landwirten ohne Land gedeckt. Während sich die neue vermögende Unternehmerklasse Villen in Wilten, Pradl und dem Saggen bauen ließ und mittlere Angestellte in Wohnhäusern in denselben Vierteln wohnten, waren die Arbeiter in Arbeiterwohnheimen und Massenunterkünften untergebracht. Die einen sorgten in Betrieben wie dem Gaswerk, dem Steinbruch oder in einer der Fabriken für den Wohlstand, während ihn die anderen konsumierten. Schichten von 12 Stunden in engen, lauten und rußigen Bedingungen forderten den Arbeitern alles ab. Zu einem Verbot der Kinderarbeit kam es erst ab den 1840er Jahren. Frauen verdienten nur einen Bruchteil dessen, was Männer bekamen. Die Arbeiter wohnten oft in von ihren Arbeitgebern errichteten Mietskasernen und waren ihnen mangels eines Arbeitsrechtes auf Gedeih und Verderb ausgeliefert. Es gab weder Sozial- noch Arbeitslosenversicherungen. Wer nicht arbeiten konnte, war auf die Wohlfahrtseinrichtungen seines Heimatortes angewiesen. Angemerkt sei, dass sich dieser für uns furchterregende Alltag der Arbeiter nicht von den Arbeitsbedingungen in den Dörfern unterschied, sondern sich daraus entwickelte. Auch in der Landwirtschaft waren Kinderarbeit, Ungleichheit und prekäre Arbeitsverhältnisse die Regel.

However, industrialisation did not only affect everyday material life. Innsbruck experienced the kind of gentrification that can be observed today in trendy urban neighbourhoods such as Prenzlauer Berg in Berlin. The change from the rural life of the village to the city involved more than just a change of location. In one of his texts, the Innsbruck writer Josef Leitgeb tells us how people experienced the urbanisation of what was once a rural area:

„…viel fremdes, billig gekleidetes Volk, in wachsenden Wohnblocks zusammengedrängt, morgens, mittags und abends die Straßen füllend, wenn es zur Arbeit ging oder von ihr kam, aus Werkstätten, Läden, Fabriken, vom Bahndienst, die Gesichter oft blaß und vorzeitig alternd, in Haltung, Sprache und Kleidung nichts Persönliches mehr, sondern ein Allgemeines, massenhaft Wiederholtes und Wiederholbares: städtischer Arbeitsmensch. Bahnhof und Gaswerk erschienen als Kern dieser neuen, unsäglich fremden Landschaft.“

For many Innsbruck residents, the revolutionary year of 1848 and the new economic circumstances led to bourgeoisie. There were always stories of people who rose through the ranks with hard work, luck, talent and a little financial start-up aid. Well-known Innsbruck examples outside the hotel and catering industry that still exist today are the Tyrolean stained glass business, the Hörtnagl grocery store and the Walde soap factory. Successful entrepreneurs took over the former role of the aristocratic landlords. Together with the numerous academics, they formed a new class that also gained more and more political influence. Beda Weber wrote in 1851: „Their social circles are without constraint, and there is a distinctly metropolitan flavour that is not so easy to find elsewhere in Tyrol."

The workers also became bourgeois. While the landlord in the countryside was still master of the private lives of his farmhands and maidservants and was able to determine their lifestyle up to and including sexuality via the release for marriage, the labourers were now at least somewhat freer individually. They were poorly paid, but at least they now received their own wages instead of board and lodging and were able to organise their private affairs for themselves without the landlord's guardianship.

The downside of this newfound self-determination was particularly evident in the first decades of industrialisation. There was hardly any state infrastructure for health and family care. Health care, pensions, old people's homes and kindergartens had not yet been invented, and in many cases the extended farming family had taken over these tasks until then. In the working-class neighbourhoods, unsupervised children romped around during the day: the youngest children, who were not yet subject to compulsory schooling, were particularly affected. In 1834, following an appeal by the Tyrolean provincial governor, a women's association was founded, which Child detention centres in the working-class neighbourhoods of St. Nikolaus, Dreiheiligen and Angerzell, now Museumstraße. The aim was not only to keep the children off the streets and provide them with clothing and food, but also to teach them manners, proper expression and virtuous behaviour. With a strict hand for "cleanliness, order and obedience", the wardens ensured that the children received at least a minimum level of care. The former Preservation centre in Paul-Hofhaimer-Gasse behind the Ferdinandeum still exists today. The classicist building now houses the Caritas integration kindergarten and a company kindergarten run by the state of Tyrol.

Innsbruck is not a traditional working-class city. Nevertheless, Tyrol never saw the formation of a significant labour movement as in Vienna. Innsbruck has always been predominantly a commercial and university city. Although there were social democrats and a handful of communists, the number of workers was always too small to really make a difference. May Day marches are only attended by the majority of people for cheap schnitzel and free beer. There are hardly any other memorials to industrialisation and the achievements of the working class. In St.-Nikolaus-Gasse and in many tenement houses in Wilten and Pradl, a few houses have been preserved that give an impression of the everyday life of Innsbruck's working class.

The Wallschen and the Fatti di Innsbruck

Prejudice and racism towards immigrants were and are common in Innsbruck, as in all societies. Whether Syrian refugees since 2015 or Turkish guest workers in the 1970s and 80s, the foreign usually generates little well-disposed animosity in the average Tyrolean. Today, Italy may be Innsbruck's favourite travel destination and pizzerias part of everyday gastronomic life, but for a long time our southern neighbours were the most suspiciously eyed population group. What the Viennese Jew and Brick Bohemia were the Tyrolean's Wall's.

The aversion to Italians in Innsbruck can look back on a long tradition. Although Italy did not exist as an independent state, the political landscape was characterised by many small counties, city states and principalities between Lake Garda and Sicily. The individual regions also differed in terms of language and culture. Nevertheless, over time people began to see themselves as Italians. During the Middle Ages and the early modern period, they were mainly resident in Innsbruck as members of the civil service, courtiers, bankers or even wives of various sovereigns. The antipathy between Italians und Germans was mutual. Some were regarded as dishonourable, unreliable, snobbish, vain, morally corrupt and lazy, others as uncivilised, barbaric, uneducated and pigs.

With the wars between 1848 and 1866, hatred of all things Italian reached a new high in the Holy Land Tyrolalthough many Wallsche served in the k.u.k. army and most of the rural population among the Italian-speaking Tyroleans were loyal to the monarchy. The Italians under Garibaldi were regarded as godless rebels and republicans and were castigated from the church pulpits between Kufstein and Riva del Garda in both Italian and German.

The Tyrolean press landscape, which experienced an upswing after liberalisation in 1867, played a major role in the conflict. What today Social Media The newspapers of the time took over the role of the press, which contributed to social division. Conservatives, Catholics, Greater Germans, liberals and socialists each had their own press organs. Loyal readers of these hardly neutral papers lived in their opinion bubble. On the Italian side, the socialist Cesare Battisti (1875 - 1916), who was executed by the Austrian military during the war for high treason on the gallows, stood out. The journalist and politician, who had studied in Vienna and was therefore considered by many to be not just an enemy but a traitor, fuelled the conflict in the newspapers Il Popolo und L'Avvenire repeatedly fired with a sharp pen.

Associations also played a key role in the hardening of the fronts. Not only had the press law been reformed in 1867, but it was now also easier to found associations. This triggered a veritable boom. Sports clubs, gymnastics clubs, theatre groups, shooting clubs and the Innsbrucker Liedertafel often served as a kind of preliminary organisation that took a political stance and also agitated. The club members met in their own pubs and organised regular club evenings, often in public. The student fraternities were particularly politically active and extremist in their opinions. The young men came from the upper middle classes or the aristocracy and were used to buying and carrying weapons. A third of the students in Innsbruck belonged to a fraternity, of which just under half were of German nationalist orientation. Unlike today, it was not uncommon for them to appear in public in their full dress uniform, complete with sabre, beret and ribbon, often armed with a cane and revolver.

It is therefore not surprising that their habitat was a particular flashpoint. One of the biggest political points of contention in the autonomy debate and the desire to join the Kingdom of Italy was a separate Italian university. The loss of Padua meant that Tyroleans of Italian descent no longer had the opportunity to study in their native language at home. Although attending the university was actually only a matter for a small elite, irredentist, anti-Austrian Tyrolean members of parliament from Trentino were able to emotionally charge the issue again and again as a symbol of the desired autonomy and fuelled hatred of Habsburg. The debate as to whether a university in Trieste, the favoured location of the Italian-speaking representatives, Innsbruck, Trento or Rovereto should be targeted, went on for years. Wilhelm Greil was admonished for his incorrect behaviour towards the Italian population by the Imperial-Royal Governor. All language groups within the monarchy were to be treated equally by law from 1867 onwards.

A look at the statistics shows just how great the fears of German nationalists that Italian students would overrun the country were. Even then, facts were often replaced in the discourse by gut feelings and racially motivated populism. After the incorporation of Pradl and Wilten in 1904, Innsbruck had just over 50,000 inhabitants. The proportion of students was just over 1000 and less than 2%. Of the approximately 3000 people of Italian descent, most of them Welschtiroler from Trentino, only just over 100 were enrolled at the university. The majority of the Wallschen made up labourers, innkeepers, traders and soldiers. Many had been living in and around Innsbruck for a long time. Many settled in Wilten in particular. Soon a small diaspora came together in the somewhat more favourable workers' village on the lower town square. Anton Gutmann sold Italian wines in his winery cooperative Riva in Leopoldstraße 30, and across the street you could eat well and cheaply at the Gasthaus Steneck specialities south of the Brenner. The majority were part of a different everyday culture, but as subjects of the monarchy they spoke excellent German; only a small proportion came from Dalmatia or Trieste and were actually foreign speakers. In keeping with the spirit of the times, they also founded sports clubs such as the Club Ciclistico oder die Unione Ginnasticasocialist-oriented workers' and consumer organisations, music clubs and student fraternities.

Although the students only made up a small proportion of them, they and the demand for an institute with Italian as the language of examination and teaching received above-average attention. Conservative and German nationalist politicians, students and the media saw an Italian university as a threat to Tyrolean Germanness. In addition to the ethnic and racist resentment towards the southern neighbours, Catholics in particular were also afraid of characters such as Cesare Battisti, who, as a socialist, embodied evil incarnate. Mayor Wilhelm Greil capitalised on the general hostility towards Italian-speaking residents and students in a similar populist manner as his Viennese counterpart Karl Lueger did in Vienna with his anti-Semitic propaganda.

After some back and forth, it was decided in September 1904 to establish a provisional law faculty in Innsbruck. This was intended to separate the students without marginalising one of the groups. From the outset, however, the project was not under a favourable star. Nobody wanted to rent the necessary premises to the university. Finally, the enterprising master builder Anton Fritz made a flat available in one of his tenement houses at Liebeneggstraße 8. At the inaugural lecture and the festive evening event in the White Cross Inn On 3 November, celebrities such as Battisti and the future Italian Prime Minister Alcide de Gasperi were in attendance. The later the evening, the more exuberant the atmosphere. When shouts of invective such as "Porchi tedeschi“ and „Abbasso Austria" (Note: German pigs and down with Austria), the situation escalated. A mob of German-speaking students armed with sticks, knives and revolvers laid siege to the White cross, in which the Italians, who were also largely armed, entrenched themselves. A troop of Kaiserjäger successfully broke up the first riot. In the process, the painter August Pezzey (1875 - 1904) was accidentally fatally wounded by an overly nervous soldier with a bayonet thrust.

The Innsbrucker Nachrichten appeared after the night-time activities on 4 November under the headline: "German blood has flowed!". The editor present reported 100 to 200 revolver shots fired by the Italians at the "Crowd of German students" who had gathered in front of the White Cross Inn. The nine wounded were listed by name, followed by an astonishingly detailed account of what had happened, including Pezzey's wound. The news of the young man's death unleashed a storm of acts of revenge and violence. As with every riot, the convinced German nationalists were joined by onlookers and rioters who enjoyed going overboard in the anonymity of the crowd without any great political conviction. While the detained Italians in the completely overcrowded prison sang the martial anthem Inno di Garibaldi the city saw serious riots against Italian restaurants and businesses. The premises of the White Cross Inn were completely vandalised except for a portrait of Emperor Franz Josef. Rioters threw stones at the residence of the governor, Palais Trapp, as his wife had Italian roots. The building in Liebeneggstraße, which Anton Fritz had made available to the university, was destroyed, as was the architect's private residence.

August Pezzey, who died in the turmoil and came from a Ladin family, was declared a "German hero" in a national frenzy by politicians and the press. He was given a grave of honour at Innsbruck's West Cemetery. At his funeral, attended by thousands of mourners, Mayor Greil read out a pathetic speech:

"...A gloriously beautiful death was granted to you on the field of honour for the German people... In the fight against impudent acts of violence you breathed your last as a martyr for the German cause..."

Reports from the Fatti di Innsbruck made it into the international press and played a decisive role in the resignation of Austrian Prime Minister Ernest von Koerber. Depending on the medium, the Italians were portrayed as dishonourable bandits or courageous national heroes, the Austrians as pan-Germanist barbarians or bulwarks against the Wallsche seen. On 17 November, just two weeks after the ceremonial opening, the Italian faculty in Innsbruck was dissolved again. The language group was denied its own university within Austria-Hungary until the end of the monarchy in 1918. The long tradition of viewing Italians as dishonourable and lazy was further fuelled by Italy's entry into the war on the side of the Entente. To this day, many Tyroleans keep the negative prejudices against their southern neighbours alive.

Art in architecture: the post-war period in Innsbruck

As after World War I, housing shortages were one of the most pressing problems after 1945. Innsbruck had suffered heavy damage during air raids, and money for new construction was scarce. When the first housing complexes were built in the 1950s, thrift was the order of the day. Many of the buildings erected from the 1950s onward may be architecturally unattractive, but they contain interesting artworks. From 1949 onward, Austria implemented the “Art in Architecture” project (Kunst am Bau). For state-funded construction projects, 2% of total expenditures were to be allocated to artistic design. The implementation of building regulations and thus the management of budgets was, as then and now, the responsibility of the federal states. Through these public commissions, artists were to be financially supported. In the lean post-war years, even successful and practically minded artists such as Oswald Haller (1908–1981), who earned money with commercial graphics and tourism posters, faced difficulties. The idea first appeared in 1919 in the Weimar Republic and was continued by the National Socialists from 1934 onward. Austria revived Kunst am Bau after the war to shape public spaces during reconstruction. The public sector, which replaced aristocracy and bourgeoisie as builders of previous centuries, was under massive financial pressure. Nevertheless, the primarily functional housing projects were not to appear entirely without ornamentation. Tyrolean artists entrusted with designing the artworks were selected through public competitions. The most famous among them was Max Weiler, perhaps the most prominent artist in post-war Tyrol, responsible for the frescoes in the Theresienkirche on the Hungerburg in Innsbruck. Other notable names include Helmut Rehm (1911–1991), Walter Honeder (1906–2006), Fritz Berger (1916–2002), and Emmerich Kerle (1916–2010). Many of these artists were shaped not only by the Federal Trade School in Innsbruck (today’s HTL) and the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna but also by the collective experience of National Socialism and the war. Fritz Berger had lost his right arm and an eye and had to learn to work with his left hand. Kerle served in Finland as a war painter and was taught at the Academy by Josef Müllner, an artist who entered art history with busts of Adolf Hitler, Siegfried from the Nibelungen saga, and the still controversial Karl Lueger monument in Vienna. Like much of the Tyrolean population, these artists—as well as politicians and officials—wanted peace and quiet after the harsh and painful war years, to let the grass grow over the events of the past decades. The works created under Kunst am Bau reflect this attitude toward a new moral order. It was the first time abstract, formless art entered Innsbruck’s public space, albeit only in an uncritical context. Fairy tales, legends, and religious symbols were popular motifs immortalized in sgraffitos, mosaics, murals, and statues. One could speak of a kind of second wave of Biedermeier art, symbolizing the petty-bourgeois lifestyle of people after the war. Art was also intended to create a new awareness and image of what was considered typically Austrian. As late as 1955, every second Austrian still regarded themselves as German. The various motifs depict leisure activities, clothing styles, and notions of social order and norms of the post-war era. Women were often shown in traditional dress and dirndls, men in lederhosen. Conservative ideals of gender roles were reflected in the art: hardworking fathers, dutiful wives caring for home and hearth, and children diligently learning at school were the ideal image well into the 1970s—a life like in a Peter Alexander film. Those who walk attentively through the city will find many of these still-visible artworks on houses in Pradl and Wilten. The mix of unremarkable architecture and contemporary artworks from the often-suppressed, long-idealized post-war era is worth seeing. Particularly beautiful examples can be found on façades in Pacherstraße, Hunoldstraße, Ing.-Thommenstraße, Innrain, at the Landesberufsschule Mandelsbergerstraße, or in the courtyard between Landhausplatz and Maria-Theresien-Straße.

The Bocksiedlung and Austrofascism

In addition to hunger, political polarisation characterised people's lives in the 1920s and 1930s. Although the collapse of the monarchy had brought about a republic, the two major popular parties, the Social Democrats and the Christian Socials, were as hostile to each other as two scorpions. Both parties set up paramilitary blocs to back up their political agenda with violence on the streets if necessary. The Republican Defence League on the side of the Social Democrats and various Christian-social or even monarchist-orientated Home defenceFor the sake of simplicity, the different groups will be summarised under this collective term, were like civil war parties. Many politicians and functionaries on both sides had fought at the front during the war and were correspondingly militarised. The Tiroler Heimatwehr was able to rely on better infrastructure and a political network in rural Tyrol thanks to the support of the Catholic Church. On 12 November 1928, the tenth anniversary of the founding of the Republic, 18,000 members of the Austrian armed forces marched through the city on the First All-Austrian Homeland March to underline their superiority on the highest holiday of the domestic social democracies. The Styrian troops were quartered in Wilten Abbey, among other places.

From 1930, the NSDAP also became increasingly present in the public sphere. It was able to gain supporters, particularly among students and young, disillusioned workers. By 1932, the party already had 2,500 members in Innsbruck. There were repeated violent clashes between the opposing political groups. The so-called Höttinger Saalschlacht Hötting was not yet part of Innsbruck at that time. The community was mainly inhabited by labourers. In this red National Socialists planned a rally in the Tyrolean bastion at the Gasthof Golden Beara meeting place for the Social Democrats. This provocation ended in a fight that resulted in over 30 people being injured and one death from a stab wound on the National Socialist side. The riots spread throughout the city, with the injured even clashing in the hospital. Only with the help of the gendarmerie and the army was it possible to separate the opponents.

After years of civil war-like conditions, the Christian Socialists under Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß (1892 - 1934) prevailed in 1933 and eliminated parliament. There was no significant fighting in Innsbruck. On 15 March, the party house of the Social Democratic Labour Party Tyrol im Hotel Sonne The Republican Protection League leader Gustav Kuprian was arrested for high treason and the individual groups disarmed. Dollfuß's goal was to establish the so-called Austrian corporative statea one-party state without opposition, curtailing elementary rights such as freedom of the press and freedom of assembly. In Tyrol in 1933, the Tiroler Wochenzeitung was newly founded to function as a party organ. The entire state apparatus was to be organised along the lines of Mussolini's fascism in Italy under the Vaterländischen Front united: Anti-socialist, authoritarian, conservative in its view of society, anti-democratic, anti-Semitic and militarised. The Innsbruck municipal council was reduced from 40 to 28 members. Instead of free elections, they were appointed by the provincial governor, which meant that only conservative councillors were represented.

Dollfuß was extremely popular in Tyrol, as pictures of the packed square in front of the Hofburg during one of his speeches in 1933 show. His policies were the closest thing to the Habsburg monarchy. His political course was supported by the Catholic Church. This gave him access to infrastructure, press organs and front organisations. Against the hated socialists, the Patriotic Front with their paramilitary units. They did not shy away from repression and acts of violence against life and limb and the facilities of political opponents. Socialists, social democrats, trade unionists and communists were repeatedly arrested. In 1934, members of the Heimwehr destroyed the monument to the Social Democrat Martin Rapoldi in Kranebitten. The press was politically controlled and censored. The articles glorified the idyllic rural life. Families with many children were supported financially. The segregation of the sexes in schools and the reorganisation of the curriculum for girls, combined with pre-military training for boys, was in the interests of a large part of the population. The traditionally orientated cultural policy, with which Austria presented itself as the better Germany under the anti-clerical National Socialist leadership appealed to the conservative part of society. As early as 1931, some Tyrolean mayors had joined forces to have the entry ban for the Habsburgs lifted, so the unspoken long-term goal of reinstalling the monarchy by the Christian Socials enjoyed broad support.

On 25 July 1934, the banned National Socialists attempted a coup in Vienna, in which Dollfuß was killed. There was also an attempted coup in Innsbruck. A policeman was shot dead in Herrengasse when a group of National Socialists attempted to take control of the city. Hitler, who had not ordered the attacks, distanced himself, and the Austrian groups of the banned party were restricted as a result. In Innsbruck, the "Verfügung des Regierungskommissärs der Landeshauptstadt Tirols“ der Platz vor dem Tiroler Landestheater als Dollfußplatz led. Dollfuß had met with the Tyrolean Heimwehr leader Richard Steidle at a rally here two weeks before his death. Steidle himself had been the victim of political violence on several occasions. In 1932, he was attacked on the tram after the Höttinger Saalschlacht, and the following year he was the victim of an assassination attempt in front of his house in Leopoldstraße. After the NSDAP seized power, he was sent to Buchenhausen concentration camp, where he died in 1940.

Dollfuß' successor as Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg (1897 - 1977) was a Tyrolean by birth and a member of the Innsbruck student fraternity Austria. He ran a law firm in Innsbruck for a long time. In 1930, he founded a paramilitary unit called Ostmärkische Sturmscharenwhich formed the counterweight of the Christian Socials to the radical Heimwehr groups. After the February Uprising in 1934, as Minister of Justice in the Dollfuß cabinet, he was jointly responsible for the execution of several Social Democrats.

However, Austrofascism was unable to turn the tide in the 1930s, especially economically. The economic crisis, which also hit Austria in 1931 and fuelled the radical, populist policies of the NSDAP, hit hard. State investment in major infrastructure projects came to a standstill. The unemployment rate in 1933 was 25%. The restriction of social welfare, which was introduced at the beginning of the First Republick was introduced had dramatic effects. The long-term unemployed were excluded from receiving social benefits as "Discontinued" excluded. Poverty caused the crime rate to rise, and robberies, muggings and thefts became more frequent.

As in previous decades, the housing situation was a particular problem. Despite the city's efforts to create modern living space, many Innsbruck residents still lived in shacks. Bathrooms or one bedroom per person were the exception. Since the great growth of Innsbruck from the 1880s onwards, the housing situation was precarious for many people. The railways, industrialisation, refugees from the German-speaking regions of Italy and the economic crisis had pushed Innsbruck to the brink of the possible. After Vienna, Innsbruck had the second highest number of residents per house. Rents for housing were so high that workers often slept in stages in order to share the costs. Although new blocks of flats and homeless shelters were built, especially in Pradl, such as the workers' hostel in Amthorstraße in 1907, the hostel in Hunoldstraße and the Pembaurblock, this was not enough to deal with the situation. Out of this need and despair, several shanty towns and settlements emerged on the outskirts of the city, founded by the marginalised, the desperate and those left behind who found no place in the system. In the prisoner-of-war camp in the Höttinger Au, people took up residence in the barracks after they had been invalided out. The best known and most notorious to this day was the Bocksiedlung on the site of today's Reichenau. From 1930, several families settled in barracks and caravans between the airport, which was located there at the time, and the barracks of the Reichenau concentration camp. The legend of its origins speaks of Otto and Josefa Rauth as the founders, whose caravan was stranded here. Rauth was not only economically poor, but also morally poor as an avowed communist in Tyrolean terms. His raft, the Noah's Ark, which he wanted to use to reach the Soviet Union via the Inn and Danube, anchored in front of Gasthof Sandwirt.

Gradually, an area emerged on the edge of both the town and society, which was run by the unofficial mayor of the estate, Johann Bock (1900 - 1975), like an independent commune. He regulated the agendas in his sphere of influence in a rough and ready manner.

The Bockala had a terrible reputation among the good citizens of the city. And despite all the historical smoothing and nostalgia, probably not without good reason. As helpful and supportive as the often eccentric residents of the estate could be among themselves, physical violence and petty crime were commonplace. Excessive alcohol consumption was common practice. The streets were unpaved. There was no running water, sewage system or sanitary facilities, nor was there a regular electricity supply. Even the supply of drinking water was precarious for a long time, which brought with it the constant risk of epidemics.

Many, but not all, of the residents were unemployed or criminals. In many cases, it was people who had fallen through the system who settled in the Bocksiedlung. Having the wrong party membership could be enough to prevent you from getting a flat in Innsbruck in the 1930s. Karl Jaworak, who carried out an assassination attempt on Federal Chancellor Prelate Ignaz Seipel in 1924, lived at Reichenau 5a from 1958 after his imprisonment and deportation to a concentration camp during the Nazi regime.

The furnishings of the Bocksiedlung dwellings were just as heterogeneous as the inhabitants. There were caravans and circus wagons, wooden barracks, corrugated iron huts, brick and concrete houses. The Bocksiedlung also had no fixed boundaries. Bockala In Innsbruck, being a citizen was a social status that largely originated in the imagination of the population.

Within the settlement, the houses and carriages built were rented out and sold. With the toleration of the city of Innsbruck, inherited values were created. The residents cultivated self-sufficient gardens and kept livestock, and dogs and cats were also on the menu in meagre times.

The air raids of the Second World War exacerbated the housing situation in Innsbruck and left the Bocksiedlung grow. At its peak, there are said to have been around 50 accommodations. The barracks of the Reichenau concentration camp were also used as sleeping quarters after the last imprisoned National Socialists held there were transferred or released, although the concentration camp was not part of the Bocksiedlung in the narrower sense.

The beginning of the end was the 1964 Olympic Games and a fire in the settlement a year earlier. Malicious tongues claim that this was set to speed up the eviction. In 1967, Mayor Alois Lugger and Johann Bock negotiated the next steps and compensation from the municipality for the eviction, reportedly in an alcohol-fuelled atmosphere. In 1976, the last quarters were evacuated due to hygienic deficiencies.

Many former residents of the Bocksiedlung were relocated to municipal flats in Pradl, the Reichenau and in the O-Village quartered here. The customs of the Bocksiedlung lived on for a number of years, which accounts for the poor reputation of the urban apartment blocks in these neighbourhoods to this day.

A reappraisal of what many historians call the Austrofascism has hardly ever happened in Austria. In the church of St Jakob im Defereggen in East Tyrol or in the parish church of Fritzens, for example, pictures of Dollfuß as the protector of the Catholic Church can still be seen, more or less without comment. In many respects, the legacy of the divided situation of the interwar period extends to the present day. To this day, there are red and black motorists' clubs, sports associations, rescue organisations and alpine associations whose roots go back to this period.

The history of the Bocksiedlung was compiled in many interviews and painstaking detail work by the city archives for the book "Bocksiedlung. A piece of Innsbruck" of the city archive.