Cafe Katzung / Trautsonhaus / Weinhaus Happ

Herzog-Friedrich-Straße 14 / 16 / 22

Trautsonhaus & Cafe Katzung

Herzog-Friedrich-Straße is home to some of Innsbruck’s most beautiful Gothic buildings. In the 15th century, stone houses gradually replaced the old wooden structures. When Innsbruck was elevated to the status of a princely residence city, the clientele changed and prosperity increased. Real estate was meant to reflect this new status. It’s worth taking a closer look at the façades, bay windows, reliefs, and frescoes. Three particularly fine examples can be found in the early modern row of houses opposite the city tower.

The Katzunghaus was first mentioned in records in 1455. Notable are the reliefs on the bay window created by the Türing family in 1530, depicting a late medieval tournament. Today, it houses the city’s oldest continuously operating coffeehouse. Court confectioner Anton Georg Katzung opened this Innsbruck institution in 1793. Interestingly, unlike earlier inns that bore animal names such as Eagle, Bear, or Stag, Katzung confidently chose his own name for the establishment. Later owners of Innsbruck cafés and patisseries, such as Munding and Café Grabhofer, followed his example. What was new about cafés was that they were public places aimed primarily at the local urban bourgeoisie. Unlike inns, which mainly accommodated travelers, cafés allowed the bourgeoisie and minor nobility to meet without seeming disreputable. Going out and being seen in a public establishment became respectable. Katzung was the first to offer a billiard table to the general public—a pastime previously reserved for aristocrats in their salons and upper-class university students. More recent is the iconic 1950s-style lettering on the façade.

Also worth seeing is the Trautsonhaus. The building was named after hereditary marshal Hans Freiherr von Trautson, who acquired it in 1541. This building, too, is a masterpiece by Gregor Türing. The Gothic sandstone bay windows are richly decorated with strictly symmetrical, intricate ornaments, giving a good impression of the typical architecture of the time. The vaulted arcades beneath the arcades date from the transitional period between Renaissance and Gothic. The baroque fountain on a small platform was installed in 1806 under Bavarian administration and is the last fountain in the old town to survive in its original form. Where tourists now refresh themselves and Christmas market visitors clean their hands of pastry grease or mulled wine, fruit, vegetables, and laundry were once washed. The building underwent major renovations in 1889 and again after World War II air raids. During these works, the ornate paintings that still adorn the façade were uncovered. A brief visit to the Gothic courtyard is worthwhile. It shows the classic structure of Innsbruck’s stone residential houses of the time, with shaft and staircase.

Weinhaus Happ

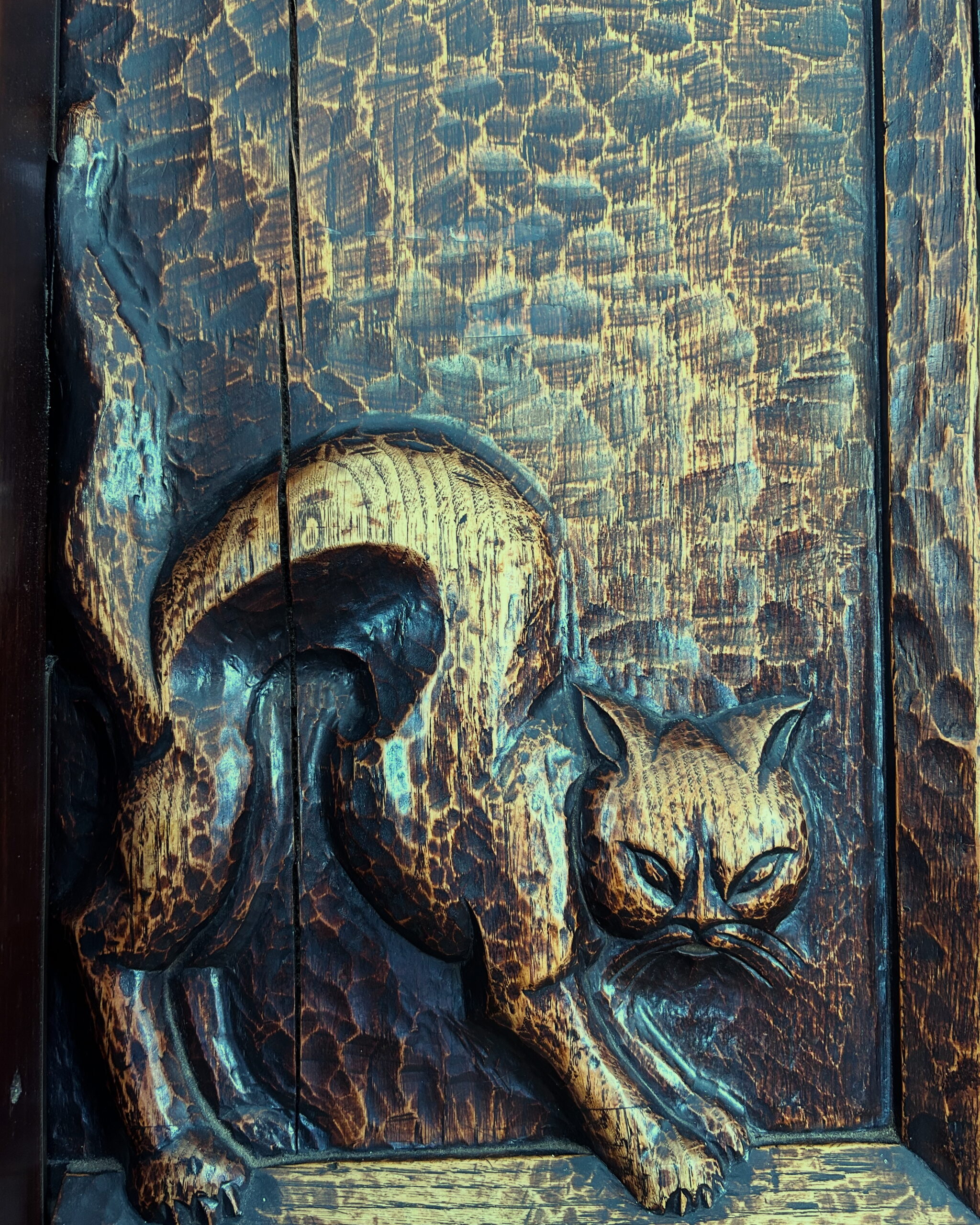

Particularly Gothic—though not original from the 16th century—is the Weinhaus Happ. From the 15th century onward, the wine trade flourished here. In 1427, Tyrolean sovereign Friedrich IV granted Innsbruck innkeepers permission to serve wine. Innsbruck has always been an important hub for wine trade heading north. The city lies on the imaginary border between beer and wine regions: in cooler northern Europe, beer was the drink of choice, while Mediterranean countries favored wine. Innsbruck’s role as a trading city and its residents’ drinking habits were—and still are—influenced by both sides of this wine-beer divide. The building was first officially listed as an inn in 1783 under beer host Martin Juffing. After numerous changes of ownership, Franz Happ took over the establishment in 1874. Like many old town buildings, Weinhaus Happ was in a deplorable state by the late 19th century after years of neglect. Following a complete collapse of the façade, it had to be renovated for the first time. After the difficult war years, Maria Schwarz took over in 1921, and gradually the Happ became an Innsbruck institution. Like many other venues, the tavern next to the Golden Roof also hosted theater performances. Its current striking appearance dates back to six years later, when the then-unknown Franz Baumann (1892–1974) redesigned the building inside and out. The challenge was to renovate and modernize the building without disturbing the cityscape. Recently, the Tyrolean Heritage Protection Association and the district administration had gained the final say on construction projects in sensitive locations. Urban planning was not to be done on the drawing board but with respect for historic town centers. Baumann designed the façade in the cubic style of New Objectivity. He planned the intricately carved entrance door, the prominent house sign, the staircase, the dining rooms, and the furnishings as a harmonious whole. Instead of a fully paneled parlor, Baumann used wood sparingly. By employing new materials, he succeeded in bringing Tyrolean style and the coziness of the traditional tavern into the modern era. The central bay window was a popular design element of the time, also used by his brother-in-law Theodor Prachensky in the building above the passage to the savings bank in Maria-Theresien-Straße. The room inside was lovingly renamed Baumannstube after Baumann rose to prominence as one of the leading architects of his time. The façade paintings of Weinhaus Happ also date from the interwar period. In 1937, Erich Torggler created South Tyrolean rural motifs, including an image of Saint Urban, the patron saint of winemakers. The different climatic conditions north and south of the main Alpine ridge led to different cultivation methods. While wine in the south was mainly an export product, North Tyrol had to import wine as well as wheat. Farmers’ interests in the individual regions differed greatly when it came to tariffs. The sovereign had to continually fine-tune the tax system to satisfy all interests and necessities as best as possible. Weinhaus Happ can be seen as a symbol of the differences in agriculture between Tyrol north and south of the Brenner Pass, while at the same time representing the unity of the land—a feeling still shared by many people today.

Colonial goods, coffee and enlightenment

Legend has it that when the Turks besieged Vienna in 1683, they brought two things to Austria that have had a lasting influence on breakfast to this day: The crescent-shaped croissant and coffee. How it actually happened that the exotic drink made its way from the growing regions overseas to the German-speaking world is probably no longer clear, but it was probably not sacks full of coffee beans left behind on the battlefield outside Vienna. This urban legend can probably be traced back to the late 17th century, when the coffee bean began to establish itself as a luxury food for the political and economic elite in Europe. It was the era of the great trading companies, the first stock exchanges and the philosophers, legal scholars and economists of the early Enlightenment, in which the lucrative overseas trade brought the coffee bean and the economic sectors that developed from it to the cities of Europe. As part of the Habsburg Empire and a trading city, Innsbruck had been part of imperial business since the 16th century. Long-distance trade was an integral part of the economy. Thanks to the Inn Bridge and its favourable position, the city had been integrated into European networks since the 12th century. The city's wealthy elite, who also had political influence through the city council, were largely drawn from the merchant class.

At the beginning of the 18th century, coffee appeared in Innsbruck's legislation for the first time, which is a strong indication that it was crossing the threshold of importance within the city. In 1713, the city council decided to authorise the purchase of coffee exclusively in pharmacies. Similar to Red Bull In the 1990s, the exotic drink was suspected of being disreputable. As demand increased in the climate of enlightenment during the time of Emperor Joseph II and the luxury drink became more and more popular in society, the regulations were relaxed. However, coffee was still not an everyday drink, but an exclusive and expensive pleasure for eccentric elites. Speciality shops, spice and food shops began to sell coffee. The still existing Innsbruck coffee brand Nosko claims the title of the city's oldest roastery as the successor to Josef Ulrich Müller's Spezerei in Seilergasse 18, which opened in 1751. Also Unterberger&Comp colonial goods, Innsbruck's second coffee roastery, which still exists today, began as a speciality shop. Jakob Fischnaller took over a shop that had been located in the historic city centre since 1660, where he sold coffee from 1768.

The bean's triumphal march began with the first coffee cafés at the end of the 1750s. The first establishments still had little to do with the Viennese coffee house culture that is known worldwide today. In 1793, the Cafe Katzung opened its doors to the wealthy bourgeoisie, who began to conquer the public space for themselves with billiard tables and newspaper stands. 50 years later, there were already 8 coffee houses in little Innsbruck. Unlike traditional inns, they symbolised a new, urban and enlightened lifestyle, a distinguishing feature between the city and the surrounding area. For a long time, wine and beer had been the everyday drinks of the masses. Even if wine was not particularly strong in the Middle Ages, it did dull the senses. Spirits were popular among the working class, and home-distilled schnapps was both popular and problematic in the countryside. Those who took care of themselves stayed away from it. Coffee, on the other hand, made people alert and productive and favoured the new virtues of industriousness and hard work. In cities like Innsbruck, the willing subject was increasingly replaced by the critical, newspaper-reading citizen. By savouring the expensive colonial goods, connoisseurs who knew how to distinguish the cheap brew, mixed with all kinds of fillers, from real coffee beans and could afford it, were able to distinguish themselves from the lower classes. Pofl stand out. When Napoleon banned the import of coffee in the territories under his control in 1810 in order to weaken the British economy, which was based on long-distance trade, there were fierce protests throughout Europe. Fig and chicory coffee as a substitute product was not particularly popular with the general public, as would later be the case during the world wars.

The colonial goods trade, which linked the exploitative business models of African coffee plantations, American tobacco plantations and South American fruit plantations with the Alps, reached a high point in Innsbruck, as in the entire German-speaking region, from the end of the 19th century, when the European powers' race for Africa entered the home straight. In 1900, there were around 40 colonial goods traders in Innsbruck. These were mostly speciality shops and general merchants who sold various, usually expensive goods from all over the world. Above all, luxury goods such as rum, tobacco, cocoa, tea and coffee or exotic fruits such as bananas were sold as colonial goods to the wealthy Innsbruck bourgeoisie. From this time onwards, the Viennese coffee house culture with all its peculiarities finally became the standard for the bourgeois culture of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Monarchy. No matter where you were between Innsbruck in the west and Czernowitz in the east of the vast empire, you could be sure of finding a railway station, an appropriate hotel and a coffee house with German-speaking staff and a similar menu and furnishings. Coffee houses, unlike traditional inns, were places where not only the aristocracy and new elites, but also men and women, albeit often in separate areas as in the Cafe Munding, could spend time.

Neither coffee house culture nor colonial goods shops disappeared from everyday life in the Republic of Austria with the caesura of the First World War and the end of the monarchy. In the 1930s, around 60 of these shops were located in Innsbruck. There were still no supermarkets with the large product ranges of today, and purchases were still made at market stalls or in small shops. The „Purchasing Association of Specie and Colonial Goods Wholesalers North Tyrol Ges.m.b.H“. It was only after the Second World War that the term "Kolonialwaren" disappeared from the city's trade directories and was replaced by the terms "Kaffeerösterei" and "Fruchtimport". Not only the Viennese coffee house culture has come to stay. Katzung, Munding and Central are still some of the oldest of their kind in Innsbruck. The Ischia company has been selling exotic fruits in the city since 1884 and is still prominently represented in the cityscape today with its striking logo on the company building next to the new city library. A brass sign at Herzog-Friedrich-Straße 26 and a large version of the logo with the merchant ship on the main traffic artery Egger-Lienz-Straße near Westbahnhof bear witness to the presence of the Unterberger brand. The logo of Praxmarer Kaffee, which shows a kneeling Moor with an offered cup on a façade in Amraserstraße, is much more conflict-laden. The traditional company itself no longer exists, but there is still a trade in tropical fruit with the same name, Praxmarer Obst.

Franz Baumann and Tyrolean modernism

The First World War not only brought ruling dynasties and empires to an end, the 1920s also saw many changes in art, music, literature and architecture. While jazz, atonal music and expressionism failed to establish themselves in little Innsbruck, a handful of architects changed the cityscape in an astonishing way. Inspired by new forms of design such as the Bauhaus style, skyscrapers from the USA and the Soviet Modernism from the revolutionary USSR, sensational projects emerged in Innsbruck. The best-known representatives of the avant-garde who brought about this new way of designing public space in Tyrol were Lois Welzenbacher, Siegfried Mazagg, Theodor Prachensky and Clemens Holzmeister. Each of these architects had their own idiosyncrasies, making the Tiroler Moderne nur schwer eindeutig zu definieren ist. Allen gemeinsam war die Abwendung von der klassizistischen Architektur der Vorkriegszeit unter gleichzeitiger Beibehaltung typischer alpiner Materialien und Elemente unter dem Motto Form follows function. Lois Welzenbacher schrieb 1920 in einem Artikel der Zeitschrift Tyrolean highlands about the architecture of this period:

"As far as we can judge today, it is clear that the 19th century lacked the strength to create its own distinct style. It is the age of stillness... Thus details were reproduced with historical accuracy, mostly without any particular meaning or purpose, and without a harmonious overall picture that would have arisen from factual or artistic necessity."

The best-known and most impressive representative of the so-called Tiroler Moderne was Franz Baumann (1892 - 1974). Unlike Holzmeister or Welzenbacher, he had no academic training. Baumann was born in Innsbruck in 1892, the son of a postal clerk. The theologian, publicist and war propagandist Anton Müllner, alias Bruder Willram became aware of Franz Baumann's talent as a draughtsman and enabled the young man to attend the Staatsgewerbeschule, today's HTL, at the age of 14. It was here that he met his future brother-in-law Theodor Prachensky. Together with Baumann's sister Maria, the two young men went on excursions in the area around Innsbruck to paint pictures of the mountains and nature. During his school years, he gained his first professional experience as a bricklayer at the construction company Huter & Söhne. In 1910 Baumann followed his friend Prachensky to Merano to work for the company Musch & Lun zu arbeiten. Meran war damals Tirols wichtigster Tourismusort mit internationalen Kurgästen. Unter dem Architekten Adalbert Erlebach machte er erste Erfahrungen bei der Planung von Großprojekten wie Hotels und Seilbahnen. Wie den Großteil seiner Generation riss der Erste Weltkrieg auch Baumann aus Berufsleben und Alltag. An der Italienfront erlitt er im Kampfeinsatz einen Bauchschuss, von dem er sich in einem Lazarett in Prag erholte. In dieser ansonsten tatenlosen Zeit malte er Stadtansichten von Bauwerken in und rund um Prag. Diese Bilder, die ihm später bei der Visualisierung seiner Pläne helfen sollten, wurden in seiner einzigen Ausstellung 1919 präsentiert.

Baumann's breakthrough came in the second half of the 1920s. He was able to win the tenders for the remodelling of the Weinhaus Happ in the old town and the Nordkettenbahn railway. In addition to his creativity and ability to think holistically, he was also able to harmonise his architectural approach with the legal situation and the modern requirements of tendering in the 1920s. Construction was a state matter, the Tyrolean Heritage Protection Association together with the district administration, was the final authority responsible for the assessment and authorisation of construction projects. During his time in Merano, Baumann was already involved with the Homeland Security Association came into contact with it. Kunibert Zimmeter had founded this association together with Gotthard Graf Trapp in the final years of the monarchy. In "Our Tyrol. A heritage book" he wrote:

"Let us look at the flattening of our private lives, our amusements, at the centre of which, significantly, is the cinema, at the literary ephemera of our newspaper reading, at the hopeless and costly excesses of fashion in the field of women's clothing, let us take a look at our homes with the miserable factory furniture and all the dreadful products of our so-called gallantry goods industry, Things that thousands of people work to produce, creating worthless bric-a-brac in the process, or let us look at our apartment blocks and villas with their cement façades simulating palaces, countless superfluous towers and gables, our hotels with their pompous façades, what a waste of the people's wealth, what an abundance of tastelessness we must find there."

The economic boom of the late 1920s saw the emergence of a new clientele and clientele that placed new demands on buildings and therefore on the construction industry. In many Tyrolean villages, hotels had replaced churches as the largest building in the townscape. The aristocratic distance from the mountains had given way to a bourgeois enthusiasm for sport. This called for new solutions at new heights. No more grand hotels were built at 1500 m for spa holidays, but a complete infrastructure for skiers in high alpine terrain such as the Nordkette. The Tyrolean Heritage Protection Association ensured that nature and townscape were protected from overly fashionable trends, excessive tourism and ugly industrial buildings. Building projects had to blend harmoniously, attractively and appropriately into the environment. Despite the social and artistic innovations of the time, architects had to keep the typical regional character in mind. This was precisely the strength of Baumann's approach to holistic building in the Tyrolean sense. All technical functions and details, the embedding of the buildings in the landscape, taking into account the topography and sunlight, played a role for him, who was not officially allowed to use the title of architect. He thus followed the "Rules for those who build in the mountains" by the architect Adolf Loos from 1913:

Don't build picturesquely. Leave such effects to the walls, the mountains and the sun. The man who dresses picturesquely is not picturesque, but a buffoon. The farmer does not dress picturesquely. But he is...

Pay attention to the forms in which the farmer builds. For they are ancestral wisdom, congealed substance. But seek out the reason for the mould. If advances in technology have made it possible to improve the mould, then this improvement should always be used. The flail will be replaced by the threshing machine."

Baumann designed even the smallest details, from the exterior lighting to the furniture, and integrated them into his overall concept of the Tiroler Moderne in.

From 1927, Baumann worked independently in his studio in Schöpfstraße in Wilten. He repeatedly came into contact with his brother-in-law and employee of the building authority, Theodor Prachensky. From 1929, the two of them worked together to design the building for the new Hötting secondary school on Fürstenweg. Although boys and girls still had to be planned separately in the traditional way, the building was otherwise completely in keeping with the style of the Neuen Sachlichkeit and the principle Light, air and sun.

In his heyday, he employed 14 people in his office. Thanks to his modern approach, which combined function, aesthetics and economical construction, he survived the economic crisis well. Only the 1000-mark barrier, die Hitler 1934 über Österreich verhängte, um die Republik finanziell in Bredouille zu bringen, brachte sein Architekturbüro wie die gesamte Wirtschaft in Probleme. Nicht nur die Arbeitslosenquote im Tourismus verdreifachte sich innerhalb kürzester Zeit, auch die Baubranche geriet in Schwierigkeiten. 1935 wurde Baumann zum Leiter der Zentralvereinigung für Architekten, nachdem er mit einer Ausnahmegenehmigung ausgestattet diesen Berufstitel endlich tragen durfte. Im gleichen Jahr plante er die Hörtnaglsiedlung in the west of the city.

After the Anschluss in 1938, he quickly joined the NSDAP. On the one hand, like his colleague Lois Welzenbacher, he was probably not averse to the ideas of National Socialism, but on the other he was able to further his career as chairman of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts in Tyrol. In this position, he courageously opposed the destructive furore with which those in power wanted to change Innsbruck's cityscape, which did not correspond to his idea of urban planning. The mayor of Innsbruck, Egon Denz, wanted to remove the Triumphal Gate and St Anne's Column in order to make more room for traffic in Maria-Theresienstraße. The city centre was still a transit area from the Brenner Pass in the south to reach the main road to the east and west on today's Innrain. At the request of Gauleiter Franz Hofer, a statue of Adolf Hitler was to be erected in place of St Anne's Column. Hofer also wanted to have the church towers of the collegiate church blown up. Baumann's opinion on these plans was negative. When the matter made it to Albert Speer's desk, he agreed with him. From this point onwards, Baumann was no longer awarded any public projects by Gauleiter Hofer.

After being questioned as part of the denazification process, Baumann began working at the city building authority, probably on the recommendation of his brother-in-law Prachensky. Baumann was fully exonerated, among other things by a statement from the Abbot of Wilten, whose church towers he had saved, but his reputation as an architect could no longer be repaired. Moreover, his studio in Schöpfstraße had been destroyed by a bomb in 1944. In his post-war career, he was responsible for the renovation of buildings damaged by the war. Under his leadership, Boznerplatz with the Rudolfsbrunnen fountain was rebuilt as well as Burggraben and the new Stadtsäle (Note: today House of Music).

Franz Baumann died in 1974 and his paintings, sketches and drawings are highly sought-after and highly traded. Anyone who takes a close look at recent major projects such as the city library, the PEMA towers and many of Innsbruck's housing estates will recognise the approaches of the Tiroler Moderne rediscover even today.

The year 1848 and its consequences

The year 1848 occupies a mythical place in European history. Although the hotspots were not to be found in secluded Tyrol, but in the major metropolises such as Paris, Vienna, Budapest, Milan and Berlin, even in the Holy Land however, the revolutionary year left its mark. In contrast to the rural surroundings, an enlightened educated middle class had developed in Innsbruck. Enlightened people no longer wanted to be subjects of a monarch or sovereign, but citizens with rights and duties towards the state. Students and freelancers demanded political participation, freedom of the press and civil rights. Workers demanded better wages and working conditions. Radical liberals and nationalists in particular even questioned the omnipotence of the church.

In March 1848, this socially and politically highly explosive mixture erupted in riots in many European cities. In Innsbruck, students and professors celebrated the newly enacted freedom of the press with a torchlight procession. On the whole, however, the revolution proceeded calmly in the leisurely Tyrol. It would be foolhardy to speak of a spontaneous outburst of emotion; the date of the procession was postponed from 20 to 21 March due to bad weather. There were hardly any anti-Habsburg riots or attacks; a stray stone thrown into a Jesuit window was one of the highlights of the Alpine version of the 1848 revolution. The students even helped the city magistrate to monitor public order in order to show their gratitude to the monarch for the newly granted freedoms and their loyalty.

The initial enthusiasm for bourgeois revolution was quickly replaced by German nationalist, patriotic fervour in Innsbruck. On 6 April 1848, the German flag was waved by the governor of Tyrol during a ceremonial procession. A German flag was also raised on the city tower. Tricolour was hoisted. While students, workers, liberal-nationalist-minded citizens, republicans, supporters of a constitutional monarchy and Catholic conservatives disagreed on social issues such as freedom of the press, they shared a dislike of the Italian independence movement that had spread from Piedmont and Milan to northern Italy. Innsbruck students and marksmen marched to Trentino with the support of the k.k. The Innsbruck students and riflemen moved into Trentino to nip the unrest and uprisings in the bud. Well-known members of this corps were Father Haspinger, who had already fought with Andreas Hofer in 1809, and Adolf Pichler. Johann Nepomuk Mahl-Schedl, wealthy owner of Büchsenhausen Castle, even equipped his own company with which he marched across the Brenner Pass to secure the border.

The city of Innsbruck, as the political and economic centre of the multinational crown land of Tyrol and home to many Italian speakers, also became the arena of this nationality conflict. Combined with copious amounts of alcohol, anti-Italian sentiment in Innsbruck posed more of a threat to public order than civil liberties. A quarrel between a German-speaking craftsman and an Italian-speaking Ladin got so heated that it almost led to a pogrom against the numerous businesses and restaurants owned by Italian-speaking Tyroleans.

The relative tranquillity of Innsbruck suited the imperial house, which was under pressure. When things did not stop boiling in Vienna even after March, Emperor Ferdinand fled to Tyrol in May. According to press reports from this time, he was received enthusiastically by the population.

"Wie heißt das Land, dem solche Ehre zu Theil wird, wer ist das Volk, das ein solches Vertrauen genießt in dieser verhängnißvollen Zeit? Stützt sich die Ruhe und Sicherheit hier bloß auf die Sage aus alter Zeit, oder liegt auch in der Gegenwart ein Grund, auf dem man bauen kann, den der Wind nicht weg bläst, und der Sturm nicht erschüttert? Dieses Alipenland heißt Tirol, gefällts dir wohl? Ja, das tirolische Volk allein bewährt in der Mitte des aufgewühlten Europa die Ehrfurcht und Treue, den Muth und die Kraft für sein angestammtes Regentenhaus, während ringsum Auflehnung, Widerspruch. Trotz und Forderung, häufig sogar Aufruhr und Umsturz toben; Tirol allein hält fest ohne Wanken an Sitte und Gehorsam, auf Religion, Wahrheit und Recht, während anderwärts die Frechheit und Lüge, der Wahnsinn und die Leidenschaften herrschen anstatt folgen wollen. Und während im großen Kaiserreiche sich die Bande überall lockern, oder gar zu lösen drohen; wo die Willkühr, von den Begierden getrieben, Gesetze umstürzt, offenen Aufruhr predigt, täglich mit neuen Forderungen losgeht; eigenmächtig ephemere- wie das Wetter wechselnde Einrichtungen schafft; während Wien, die alte sonst so friedliche Kaiserstadt, sich von der erhitzten Phantasie der Jugend lenken und gängeln läßt, und die Räthe des Reichs auf eine schmähliche Weise behandelt, nach Laune beliebig, und mit jakobinischer Anmaßung, über alle Provinzen verfügend, absetzt und anstellt, ja sogar ohne Ehrfurcht, den Kaiaer mit Sturm-Petitionen verfolgt; während jetzt von allen Seiten her Deputationen mit Ergebenheits-Addressen mit Bittgesuchen und Loyalitätsversicherungen dem Kaiser nach Innsbruck folgen, steht Tirol ganz ruhig, gleich einer stillen Insel, mitten im brausenden Meeressturme, und des kleinen Völkchens treue Brust bildet, wie seine Berge und Felsen, eine feste Mauer in Gesetz und Ordnung, für den Kaiser und das Vaterland."

In June, a young Franz Josef, not yet emperor at the time, also stayed at the Hofburg on his way back from the battlefields of northern Italy instead of travelling directly to Vienna. Innsbruck was once again the royal seat, if only for one summer. While blood was flowing in Vienna, Milan and Budapest, the imperial family enjoyed life in the Tyrolean countryside. Ferdinand, Franz Karl, his wife Sophie and Franz Josef received guests from foreign royal courts and were chauffeured in four-in-hand carriages to the region's excursion destinations such as Weiherburg Castle, Stefansbrücke Bridge, Kranebitten and high up to Heiligwasser. A little later, however, the cosy atmosphere came to an end. Under gentle pressure, Ferdinand, who was no longer considered fit for office, passed the torch of regency to Franz Josef I. In July 1848, the first parliamentary session was held in the Court Riding School in Vienna. The first constitution was enacted. However, the monarchy's desire for reform quickly waned. The new parliament was an imperial council, it could not pass any binding laws, the emperor never attended it during his lifetime and did not understand why the Danube Monarchy, as a divinely appointed monarchy, needed this council.

Nevertheless, the liberalisation that had been gently set in motion took its course in the cities. Innsbruck was given the status of a town with its own statute. Innsbruck's municipal law provided for a right of citizenship that was linked to ownership or the payment of taxes, but legally guaranteed certain rights to members of the community. Birthright citizenship could be acquired by birth, marriage or extraordinary conferment and at least gave male adults the right to vote at municipal level. If you got into financial difficulties, you had the right to basic support from the town.

Thanks to the census-based majority voting system, the Greater German liberal faction prevailed within the city government, in which merchants, tradesmen, industrialists and innkeepers set the tone. On 2 June 1848, the first edition of the liberal and Greater German-minded Innsbrucker Zeitungfrom which the above article on the emperor's arrival in Innsbruck is taken. Conservatives, on the other hand, read the Volksblatt for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. Moderate readers who favoured a constitutional monarchy preferred to consume the Bothen for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. However, the freedom of the press soon came to an end. The previously abolished censorship was reintroduced in parts. Newspaper publishers had to undergo some harassment by the authorities. Newspapers were not allowed to write against the state government, monarchy or church.

"Anyone who, by means of printed matter, incites, instigates or attempts to incite others to take action which would bring about the violent separation of a part from the unified state... of the Austrian Empire... or the general Austrian Imperial Diet or the provincial assemblies of the individual crown lands.... Imperial Diet or the Diet of the individual Crown Lands... violently disrupts... shall be punished with severe imprisonment of two to ten years."

After Innsbruck officially replaced Meran as the provincial capital in 1849 and thus finally became the political centre of Tyrol, political parties were formed. From 1868, the liberal and Greater German orientated party provided the mayor of the city of Innsbruck. The influence of the church declined in Innsbruck in contrast to the surrounding communities. Individualism, capitalism, nationalism and consumerism stepped into the breach. New worlds of work, department stores, theatres, cafés and dance halls did not supplant religion in the city either, but the emphasis changed as a result of the civil liberties won in 1848.

Perhaps the most important change to the law was the Basic relief patent. In Innsbruck, the clergy, above all Wilten Abbey, held a large proportion of the peasant land. The church and nobility were not subject to taxation. In 1848/49, manorial rule and servitude were abolished in Austria. Land rents, tithes and roboters were thus abolished. The landlords received one third of the value of their land from the state as part of the land relief, one third was regarded as tax relief and the farmers had to pay one third of the relief themselves. They could pay off this amount in instalments over a period of twenty years.

The after-effects can still be felt today. The descendants of the then successful farmers enjoy the fruits of prosperity through inherited land ownership, which can be traced back to the land relief of 1848, as well as political influence through land sales for housing construction, leases and public sector redemptions for infrastructure projects. The land-owning nobles of the past had to resign themselves to the ignominy of pursuing middle-class labour. The transition from birthright to privileged status within society was often successful thanks to financial means, networks and education. Many of Innsbruck's academic dynasties began in the decades after 1848.

Das bis dato unbekannte Phänomen der Freizeit kam, wenn auch für den größten Teil nur spärlich, auf und begünstigte gemeinsam mit frei verfügbarem Einkommen einer größeren Anzahl an Menschen Hobbies. Zivile Organisationen und Vereine, vom Lesezirkel über Sängerbünde, Feuerwehren und Sportvereine, gründeten sich. Auch im Stadtbild manifestierte sich das Revolutionsjahr. Parks wie der Englische Garten beim Schloss Ambras oder der Hofgarten waren nicht mehr exklusiv der Aristokratie vorbehalten, sondern dienten den Bürgern als Naherholungsgebiete vom beengten Dasein. In St. Nikolaus entstand der Waltherpark als kleine Ruheoase. Einen Stock höher eröffnete im Schloss Büchsenhausen Tirols erste Schwimm- und Badeanstalt, wenig später folgte ein weiteres Bad in Dreiheiligen. Ausflugsgasthöfe rund um Innsbruck florierten. Neben den gehobenen Restaurants und Hotels entstand eine Szene aus Gastwirtschaften, in denen sich auch Arbeiter und Angestellte gemütliche Abende bei Theater, Musik und Tanz leisten konnten.

Türing dynasty of master builders: Innsbruck becomes a cosmopolitan city

Siegmund der Münzreiche was the one who brought Niklas Türing (1427 - 1496) to Innsbruck in the 15th century. He made his first documented appearance in 1488. The Türings were a family of stonemasons and master builders from what is now Swabia, which at the time was part of the Habsburg Monarchy as part of Vorderösterreich. Innsbruck had been the royal seat of the Tyrolean princes for several decades, but the architectural splendour had not yet arrived north of the Alps. The city was a collection of wooden houses and not very prestigious. Golden times were dawning for craftsmen and master builders, which were to gather even more momentum under Maximilian. There was a real building boom. Aristocrats wanted to have a residence in the city in order to be as close as possible to the centre of power. In the days before the press, a functioning postal system, fax and e-mail, politics was mainly played out through direct contact.

The Türings made a career in step with the city. It is reported from 1497 that Niklas Türing was in the service of the sovereign as a "paid court mason". When he died in 1517 or 1518, it is not known for certain, he was listed on his gravestone as "Roman imperial majesty's chief foreman" is the title. Together with his son Gregor, he was listed as a master stonemason. This enabled the Türings to acquire citizenship in Innsbruck. By 1506 at the latest, they had a house in the workers' and craftsmen's neighbourhood Anbruggen. In 1509, they were able to acquire the house of today's Gasthof zum Lamm in Mariahilfstraße. Further property was added at what is now Schlossergasse 21.

In the course of the late Middle Ages, the early Gothic period and later the Renaissance gave Europe a new architectural guise with a new understanding of architecture and aesthetics. Buildings such as Notre Dame or the Minster of York set the trend that would characterise the whole of Europe until the onset of the Baroque period. Pointed towers, ribbed vaults, bay windows and playful carvings depicting everyday courtly life are some of the typical features that make the heterogeneous style recognisable. The work of the Türings can be traced particularly well in the old town centre. Many of the town houses, such as the Trautsonhaus still have Gothic ground plans, inner courtyards and carvings.

The Türings left their mark on Gothic Innsbruck in the transitional period between the Middle Ages and early modern times. Thanks to their training, they combined an eye for the big picture and details in their building projects. They were known for their particularly fine stonework, which resulted in ornate portals, arcades, staircases and vaults. They produced relief jewellery with patterns in the typical style of Renaissance art. Grotesques, vases and depictions of animals were typical ways of decorating bay windows and smooth walls. The symmetrical arrangement of the individual elements is also a characteristic of the period.

Niklas Türing is the Goldene Dachl to a large extent. He also created the statue of the Burgriesen Haidla particularly tall member of Siegmund's bodyguard, which can be seen today in the city tower. Emperor Maximilian held him in such high esteem that he allowed him to display the family coat of arms of the Türings and his wife, a fountain and a fish, in the vault of the Goldenen Dachls to immortalise him. His son Gregor immortalised himself with the Trautsonhaus in der Herzog-Friedrich-Straße und am Burgriesenhaus in the Domgasse. The last of the Türings to have an influence on the Innsbruck building scene was Niklas Türing the Younger, who began planning the Hofkirche together with Andrea Crivelli. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the influence of the Gothic style began to wane, especially in what is now Austria. Churches in particular were increasingly remodelled and rebuilt in the Baroque style as part of the Counter-Reformation. Today, Türingstraße in the east of Innsbruck is a reminder of the early modern dynasty of master builders.

The Tyrolean nation, "democracy" and the heart of Jesus

Many tyroleans see themselves as an own nation. With „Tirol isch lei oans“, „Zu Mantua in Banden“ and „Dem Land Tirol die Treue", the federal state has three more or less official anthems. As in other federal states, there are historical reasons for this pronounced local patriotism. Tyrolean freedom and independence are often invoked as a local shrine to underpin this. It is often referred to as the first democracy in mainland Europe, which is probably an exaggeration considering the feudal and hierarchical history of the country up until the 20th century. However, the country cannot be denied a certain peculiarity in its development, even if it was less about the participation of broad sections of the population and more about the local elites curtailing the power of the sovereign.

The first act was what the Innsbruck historian Otto Stolz (1881 - 1957) in the 1950s exuberantly described, in reference to English history, as the Magna Charta Libertatum celebrated. After the marriage of the Bavarian Ludwig von Wittelsbach to the Tyrolean princess Margarete von Tirol-Görz, the Bavarian Wittelsbachs were rulers of Tyrol for a short time. In order to win over the Tyrolean population to his side, Ludwig decided to offer the provincial estates a treat in the 14th century. In the Großen Freiheitsbrief of 1342, Louis promised the Tyroleans that he would not enact any laws or tax increases without first consulting the provincial estates. However, there can be no question of a democratic constitution as understood in the 21st century, as these provincial estates were primarily the aristocratic, landowning classes, who represented their interests accordingly. Although one copy of the document mentioned the inclusion of peasants as a class in the Diet, this version never became official.

As the towns and bourgeoisie gained more political clout in the 15th century due to their economic importance, a counterweight to the nobility developed within the estates. At the Diet of 1423 under Frederick IV, 18 members of the nobility met 18 members of the towns and peasantry for the first time. Gradually, a fixed composition developed in the provincial diets of the 15th and 16th centuries. The Tyrolean bishops of Brixen and Trento, the abbots of the Tyrolean monasteries, the nobility, representatives of the towns and the peasantry were all represented. The provincial governor presided over the meeting. Of course, the resolutions and wishes of the provincial parliament were not binding for the prince, but it was probably a reassuring feeling for the ruler to know that the representatives of the population were on his side or that difficult decisions were supported.

Another important document for the country was the Tiroler Landlibell. In 1511, Maximilian stipulated, among other things, that Tyrolean soldiers should only be called up for military service in defence of their own country. The reason for Maximilian's generosity was less his love for the Tyroleans than the need to keep the Tyrolean mines running instead of burning out the precious labourers and the peasantry that supplied them on the battlefields of Europe. The fact that in Landlibell At the same time, massive restrictions on the population and higher costs are often forgotten. The Landlibell regulated not only the strength of the troop contingents but also the special taxes that were levied. The nobility and clergy had to use the capital gains from their estates as a tax base, which often amounted to a rough estimate. Towns, on the other hand, were taxed according to the number of fireplaces in the houses, which could be calculated quite accurately. Coveted miners were exempt from these taxes and only had to serve in the army in extreme emergencies.

This special regulation for national defence, as laid down in the Landlibell, was one of the reasons for the uprising of 1809, when young Tyroleans were conscripted for the mobilisation of the armed forces as part of general conscription. To this day, the Napoleonic Wars, when the Catholic crown land was threatened by the "godless French" and the revolutionary social order, characterise the Tyrolean self-image. During this defensive struggle, an alliance was formed between Catholicism and Tyrol. The Tyrolean marksmen entrusted their fate to the heart of Jesus before a decisive battle against Napoleon's armies in June 1796 and entered into a covenant with God personally, which would protect their Heiliges Land Tirol was supposed to protect her. Another identity-forming legend from 1796 centres around a young woman from the village of Spinges. Katharina Lanz, who was known as the Jungfrau von Spinges went down in the history of the country as an identity-forming national heroine, is said to have motivated the almost defeated Tyrolean troops with her imperious demeanour in battle to such an extent that they were ultimately able to achieve victory over the French superiority. Depending on the account, she is said to have taught Napoleon's troops to fear with a pitchfork, a flail or a scythe similar to the French Maid Joan of Arc. Legends and traditions surrounding the marksmen and the feeling of being an independent nation chosen by God, which happened to be attached to the Republic of Austria, go back to these legends.

The particular identities of the individual crown lands did not correspond to what enlightened politicians imagined a modern state to be. Under Maria Theresa, the central state was strengthened vis-à-vis the crown lands and the local nobility. The subjects' sense of belonging should not be to the province of Tyrol, but to the House of Habsburg. In the 19th century, the aim was to strengthen identification with the monarchy and develop a national consciousness. The press, visits by the ruling family, monuments such as the Rudolfsbrunnen or the opening of Mount Isel with Hofer as a Tyrolean loyal to the emperor were intended to help turn the population into subjects loyal to the emperor.

When the Habsburg Empire collapsed after the First World War, the crown land of Tyrol also broke up. What had been known as South Tyrol until 1918, the Italian-speaking part of the province between Riva on Lake Garda and Salurn in the Adige Valley, became Trentino with Trento as its capital. The German-speaking part of the province between Neumarkt and the Brenner Pass is now South Tyrol / Alto Adige, an autonomous region of the Republic of Italy with the capital Bolzano.

Throughout the centuries, Innsbruckers have felt themselves to be Tyroleans, Germans, Catholics and subjects of the emperor. Before 1945, however, hardly anyone felt Austrian. It was only after the Second World War that a sense of belonging to Austria slowly began to develop in Tyrol. To this day, however, many Tyroleans are proud of their local identity and like to distinguish themselves from the inhabitants of other federal states and countries. For many Tyroleans, after more than 100 years, the Brenner Pass still represents a Injustice limit even if the Europa der Regionen cooperates politically across borders at EU level.

The legend of the Holy Landthe independent Tyrolean nation and the first mainland democracy has survived to this day. The bon mot "bisch a Tiroler bisch a Mensch, bisch koana, bisch a Oasch" summarises Tyrolean nationalism succinctly. The fact that the historic crown land of Tyrol was a multi-ethnic construct with Italians, Ladins, Cimbrians and Rhaeto-Romans is often overlooked in right-wing circles. Laws from the federal capital of Vienna or even the EU in Brussels are still viewed with scepticism today. Nationalists on both sides of the Brenner Pass still make use of the Jungfrau von Spingesthe heart of Jesus and Andreas Hofer, to publicise their concerns. The Säcularfeier des Bundes Tirols mit dem göttlichen Herzen Jesu was still celebrated in the 20th century with great participation from the political elite.