Western cemetery

Fritz-Pregl-Straße / Schöpfstraße

Worth knowing

It is a characteristic of urban expansion and development that infrastructure not only changes technically, but also in terms of its positioning within the municipality. Cemeteries and hospitals not only grow, but often relocate towards the new peripheral areas. When Innsbruck grew from a small community on the bridge into a city, the cemetery was moved from the parish church within the city walls next to the city hospital to today's Adolf-Pichler-Platz. The expanding Hofburg under Emperor Maximilian required the space of the old churchyard. In the 19th century, as more and more buildings grew up around the hospital church and the Gottesacker, both institutions moved westwards. The Tyrolean art historian Heinrich Hammer (1873 - 1953) described the relocation in 1923 in his book Art history guide through the buildings and monuments as follows:

„The city's oldest cemetery was located around St. Jacob's parish church; apparently because of the expanding Hofburg of Maximilian I, it was moved outside the city in 1510 to the Hl. Geist-Spitalskirche, where a Gothic double chapel (below in honour of St. Michael and St. Vitus, above St. Anne) and (1571, 1591) arcades were built as early as 1510-16. After this „old“ cemetery had been enlarged several times (1849), the city decided in 1855 to build a new cemetery in the west of the city, opened part of it in 1856 and at the same time stopped burials in the old cemetery, whose chapel and graves were then demolished in 1869 with the barbaric destruction of most of the old gravestones; its place is now taken by the state secondary school built in 1869 and the Karl Ludwig-Platz marked out in 1896.“

The relocation was not only due to a lack of space, but people's ideas on hygiene were no longer compatible with a cemetery in the centre of town. Although the enlightened Emperor Joseph II failed with his desire for more rationality when it came to death and dying, which culminated in the introduction of reusable folding coffins, new times also dawned in Catholic Tyrol in the period after 1848. In 1855, the city of Innsbruck organised a competition to design a new cemetery. The specifications were a rectangular ground plan and the design of the grounds modelled on an Italian cemetery. Campo Santo. Carl Müller succeeded with his contemporary modern design with several entrances and artistically designed arcades, which encompassed the cemeteries that are now located to the north of the blessing hall. The new cemetery was built in the summer of 1856 on the undeveloped Wilten fields south of the Innrain. The arcade was designed by Franz Plattner, August von Wörndle, Mathias Schmid and Georg Mader, one of the co-founders of Tyrolean stained glass, in a late work of the then modern, romantic Nazarene style. In 1859, Bruneck artist Josef Gröbmer (1815 - 1882) created the statue of the Risen Christ above the then main portal at the north entrance

A walk through the well-kept grounds with their old trees is like a visit to a museum and a journey into the past. The monuments and tombs not only show a wide variety of artistic styles, but also reveal a lot about the buried and the circumstances of the time. Many of the tombs, such as the monument to the Unterberger family and the neo-Gothic crypt of Innsbruck composer Josef Pembaur, are decorated with Nazarene-style paintings like the arcades and indicate the deep piety of the buried. The gravestone of the social democratic Innsbruck politician couple Maria and Martin Rapoldi, on the other hand, was designed as a mosaic in the typical matter-of-fact republican style of the interwar period. The androgynous-looking figure wears a palm branch and crown, with the city coat of arms of Innsbruck proudly emblazoned below as a secular symbol. Josef Kiebach's sparsely decorated civic grave of honour also bears the city's coat of arms. The tomb of the last governor of the imperial and royal monarchy, Josef Schraffl. Josef Schraffl (1855 - 1922), the last governor of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, has a baroque, suffering crucified figure and a stone eagle, reflecting the general mood of Tyrol, which was divided at the Brenner Pass after the First World War. Under arcade 96 is the tomb of the Greater German nationalist mayor Wilhelm Greils, who is holding German oak leaves in the hand of a veiled woman who has sprung from antiquity. The Trentino sculptor Andrea Malfatti designed the Oberer tomb in arcade 48 with the Transfiguration of Christ and the Lodron tomb Mourning figure of a girl in arcade 52 in the Italian-naturalistic style. In 1909, the Innsbruck master builder Josef Retter had a neo-Gothic chapel built in the centre of the newer, southern part of the cemetery, which could now serve as a film set thanks to its romantic ivy growth, as a family burial place. The solid wooden door is framed by a mosaic that is reminiscent of Art Nouveau.

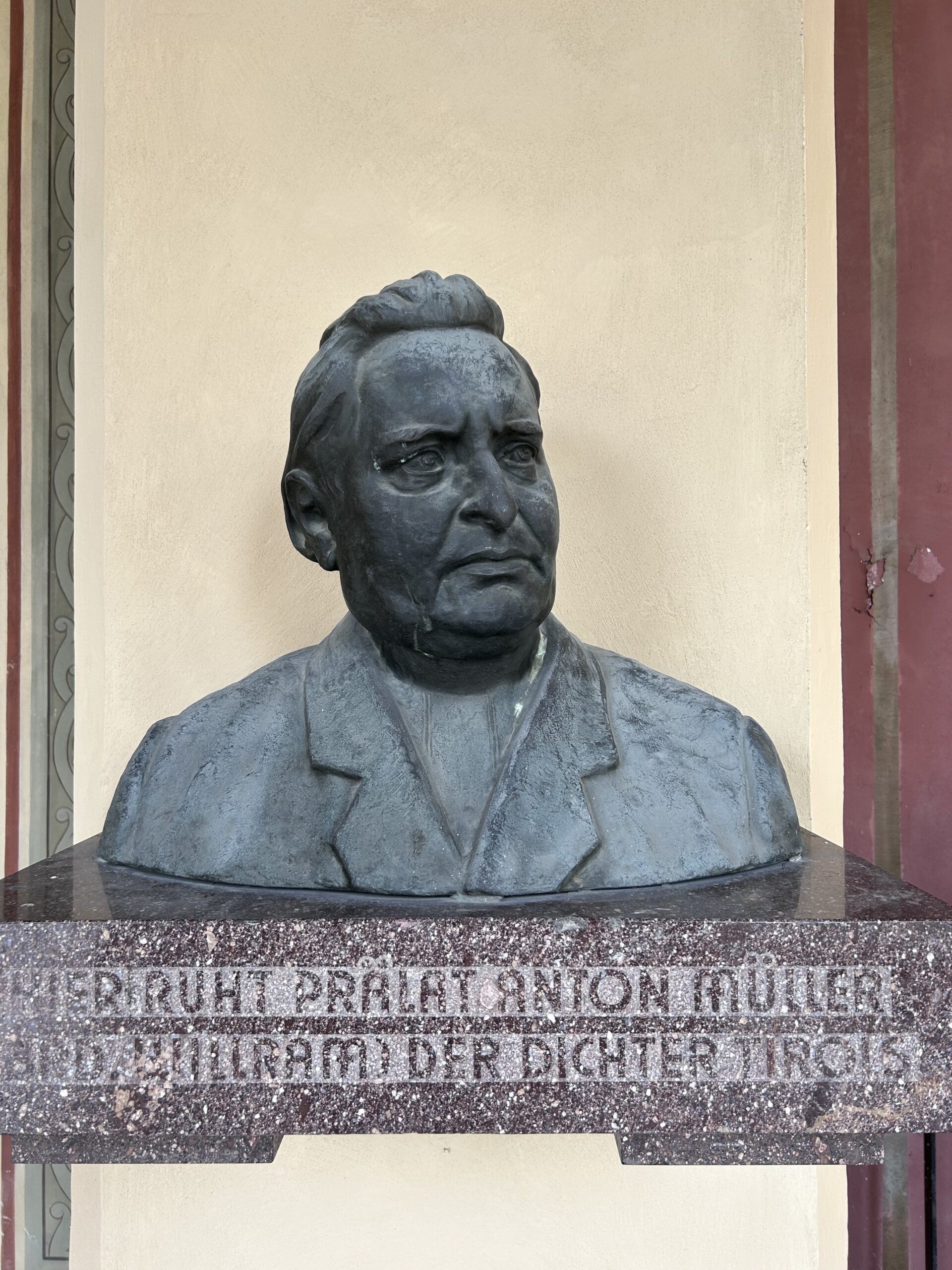

Some of the elaborately designed monuments, graves of honour and family tombs of important Innsbruck residents are quite controversial. A bust commemorates Prelate Anton Müllner, a war-mongering poet who wrote terrible works under the name of Brother Willram. The memorial to the martyrs of the striking fraternity is particularly „patriotic“ Suevia. Their motto „Freedom, honour, fatherland“, which they share with other German nationalist academic organisations such as the Libertas in Vienna, is crowned by a martial figure. The first mayor of the post-war period, Anton Melzer (1898 - 1951), who was removed from the city council after 1938 and was imprisoned for a long time in the Reichenau camp, has his artistically designed grave of honour in the immediate vicinity of the final resting place of Egon Denz, who was mayor of Innsbruck during the Nazi era.

The oldest graves of honour were transferred from the old municipal cemetery to the new central cemetery in 1858, as was the crucifix in the centre of the northern part of the complex, for example the tomb of the court sculptor under Ferdinand I Alexander Colin (1527 - 1612), who had his memorial with the Awakening of Lazarus or the representative of the early Enlightenment in Austria and Chancellor of Tyrol Josef von Hormayr (1705 - 1779). A particularly creepy monument at the north entrance commemorates this move. Josef created the ensemble in 1775 for the burial place of the Counts Wolkenstein-Trostburg, one of the oldest noble families in Tyrol. In 1873, the neo-Gothic monument was erected by the town directly in front of the main entrance. In the same year, the Innsbrucker Nachrichten praised the monument in a report about the cemetery on All Souls' Day:

„Leaving the cemetery after this brief review, we come across a well-known monument from the old cemetery, partly hidden behind cypress trees. The town council had the former Wolkenstein monument restored by the sculptor Grissemann and placed here in memory of all the remains transferred from the old cemetery. This important marble work from the end of the last century, with its somewhat foppish old man holding the hourglass over the high coffin, the Grim Reaper, and the beautiful female figure facing him, who turns away from him in horror, is an ornament to our cemetery, which has almost become a centre of Tyrolean art.“

The monument depicts Saturn, the Roman equivalent of the Greek god Chronos. The artistically designed figures in the style of classical antiquity fit in surprisingly well with the 1870s, which were characterised by the onset of historicism. Saturn was the Roman patron saint of time, agriculture and fertility. According to legend, the father of heaven devoured his own children to prevent them from depriving him of his power as ruler. However, his son Jupiter, the Greek Zeus, was saved and was able to overthrow him. The monument shows Saturn in the form of an angel of death, mercilessly holding an expired hourglass in front of a grieving woman bent over a skull, while a child at the foot of the sarcophagus covers its face with a veil.

Three years after the inauguration of the new municipal cemetery, the city opened the Protestant section to the south of the main site, which was of course structurally separated in order to maintain Catholic order in the province of Tyrol. Five years later, the Jewish section followed, also specially enclosed. The former Jewish cemetery at Judenbühel in St. Nikolaus had to be relocated after the graves had been vandalised several times. This sad story was to be repeated in 1961 during the Eichmann trials, when the Jewish section of the Westfriedhof was once again desecrated by unknown persons. In 1889, the cemetery doubled in size after the grounds had become too small in just over 30 years. The former end with the cemetery chapel became the connecting section and the main entrance was moved to the eastern end.

During the brief economic boom of the interwar period, the cemetery, which was opened in Pradl Western cemetery The complex was extended and modernised again. The chapel in the centre of the complex was rebuilt in 1927 in a cubic style with a pyramid roof according to plans by the municipal building official Franz Wiesenberg. The stone ensemble above the entrance to the new blessing hall with God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit is designed in the functional style of the interwar period. Gottlieb Schuller and Rudolf Jettmar designed the paintings, Franz Santifaller the wooden figures symbolising faith, love and hope. Inside, Tyrolean stained glass mosaics adorn the walls. The old vestibule with the frescoes End of the world, Last judgement und Heavenly Jerusalem Fortunately, Franz Plattner's remains were preserved. The cemetery was given a small urn grove in accordance with the modern ideas of the First Republic era. The change in the burial rite from the pompous Orthodox rite to a bourgeois cremation was one of the first measures in the revolutionary Soviet Union of the 1920s to manifest the renunciation of the monarchist system of Tsarism. The Social Democrats, who were strong in Innsbruck, were only able to achieve a partial success with the urn grove. The planned crematorium was too much of a good thing and, like the reusable coffin of Joseph II, was scuppered by protests from the Catholic part of Tyrol.

Believe, Church and Power

Die Fülle an Kirchen, Kapellen, Kruzifixen und Wandmalereien im öffentlichen Raum wirkt auf viele Besucher Innsbrucks aus anderen Ländern eigenartig. Nicht nur Gotteshäuser, auch viele Privathäuser sind mit Darstellungen der Heiligen Familie oder biblischen Szenen geschmückt. Der christliche Glaube und seine Institutionen waren in ganz Europa über Jahrhunderte alltagsbestimmend. Innsbruck als Residenzstadt der streng katholischen Habsburger und Hauptstadt des selbsternannten Heiligen Landes Tirol wurde bei der Ausstattung mit kirchlichen Bauwerkern besonders beglückt. Allein die Dimension der Kirchen umgelegt auf die Verhältnisse vergangener Zeiten sind gigantisch. Die Stadt mit ihren knapp 5000 Einwohnern besaß im 16. Jahrhundert mehrere Kirchen, die in Pracht und Größe jedes andere Gebäude überstrahlte, auch die Paläste der Aristokratie. Das Kloster Wilten war ein Riesenkomplex inmitten eines kleinen Bauerndorfes, das sich darum gruppierte. Die räumlichen Ausmaße der Gotteshäuser spiegelt die Bedeutung im politischen und sozialen Gefüge wider.

Die Kirche war für viele Innsbrucker nicht nur moralische Instanz, sondern auch weltlicher Grundherr. Der Bischof von Brixen war formal hierarchisch dem Landesfürsten gleichgestellt. Die Bauern arbeiteten auf den Landgütern des Bischofs wie sie auf den Landgütern eines weltlichen Fürsten für diesen arbeiteten. Damit hatte sie die Steuer- und Rechtshoheit über viele Menschen. Die kirchlichen Grundbesitzer galten dabei nicht als weniger streng, sondern sogar als besonders fordernd gegenüber ihren Untertanen. Gleichzeitig war es auch in Innsbruck der Klerus, der sich in großen Teilen um das Sozialwesen, Krankenpflege, Armen- und Waisenversorgung, Speisungen und Bildung sorgte. Der Einfluss der Kirche reichte in die materielle Welt ähnlich wie es heute der Staat mit Finanzamt, Polizei, Schulwesen und Arbeitsamt tut. Was uns heute Demokratie, Parlament und Marktwirtschaft sind, waren den Menschen vergangener Jahrhunderte Bibel und Pfarrer: Eine Realität, die die Ordnung aufrecht hält. Zu glauben, alle Kirchenmänner wären zynische Machtmenschen gewesen, die ihre ungebildeten Untertanen ausnützten, ist nicht richtig. Der Großteil sowohl des Klerus wie auch der Adeligen war fromm und gottergeben, wenn auch auf eine aus heutiger Sicht nur schwer verständliche Art und Weise. Verletzungen der Religion und Sitten wurden in der späten Neuzeit vor weltlichen Gerichten verhandelt und streng geahndet. Die Anklage bei Verfehlungen lautete Häresie, worunter eine Vielzahl an Vergehen zusammengefasst wurde. Sodomie, also jede sexuelle Handlung, die nicht der Fortpflanzung diente, Zauberei, Hexerei, Gotteslästerung – kurz jede Abwendung vom rechten Gottesglauben, konnte mit Verbrennung geahndet werden. Das Verbrennen sollte die Verurteilten gleichzeitig reinigen und sie samt ihrem sündigen Treiben endgültig vernichten, um das Böse aus der Gemeinschaft zu tilgen. Bis in die Angelegenheiten des täglichen Lebens regelte die Kirche lange Zeit das alltägliche Sozialgefüge der Menschen. Kirchenglocken bestimmten den Zeitplan der Menschen. Ihr Klang rief zur Arbeit, zum Gottesdienst oder informierte als Totengeläut über das Dahinscheiden eines Mitglieds der Gemeinde. Menschen konnten einzelne Glockenklänge und ihre Bedeutung voneinander unterscheiden. Sonn- und Feiertage strukturierten die Zeit. Fastentage regelten den Speiseplan. Familienleben, Sexualität und individuelles Verhalten hatten sich an den von der Kirche vorgegebenen Moral zu orientieren. Das Seelenheil im nächsten Leben war für viele Menschen wichtiger als das Lebensglück auf Erden, war dies doch ohnehin vom determinierten Zeitgeschehen und göttlichen Willen vorherbestimmt. Fegefeuer, letztes Gericht und Höllenqualen waren Realität und verschreckten und disziplinierten auch Erwachsene.

Während das Innsbrucker Bürgertum von den Ideen der Aufklärung nach den Napoleonischen Kriegen zumindest sanft wachgeküsst wurde, blieb der Großteil der Menschen weiterhin der Mischung aus konservativem Katholizismus und abergläubischer Volksfrömmigkeit verbunden. Religiosität war nicht unbedingt eine Frage von Herkunft und Stand, wie die gesellschaftlichen, medialen und politischen Auseinandersetzungen entlang der Bruchlinie zwischen Liberalen und Konservativ immer wieder aufzeigten. Seit der Dezemberverfassung von 1867 war die freie Religionsausübung zwar gesetzlich verankert, Staat und Religion blieben aber eng verknüpft. Die Wahrmund-Affäre, die sich im frühen 20. Jahrhundert ausgehend von der Universität Innsbruck über die gesamte K.u.K. Monarchie ausbreitete, war nur eines von vielen Beispielen für den Einfluss, den die Kirche bis in die 1970er Jahre hin ausübte. Kurz vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg nahm diese politische Krise, die die gesamte Monarchie erfassen sollte in Innsbruck ihren Anfang. Ludwig Wahrmund (1861 – 1932) war Ordinarius für Kirchenrecht an der Juridischen Fakultät der Universität Innsbruck. Wahrmund, vom Tiroler Landeshauptmann eigentlich dafür ausgewählt, um den Katholizismus an der als zu liberal eingestuften Innsbrucker Universität zu stärken, war Anhänger einer aufgeklärten Theologie. Im Gegensatz zu den konservativen Vertretern in Klerus und Politik sahen Reformkatholiken den Papst nur als spirituelles Oberhaupt, nicht aber als weltlich Instanz, an. Studenten sollten nach Wahrmunds Auffassung die Lücke und die Gegensätze zwischen Kirche und moderner Welt verringern, anstatt sie einzuzementieren. Seit 1848 hatten sich die Gräben zwischen liberal-nationalen, sozialistischen, konservativen und reformorientiert-katholischen Interessensgruppen und Parteien vertieft. Eine der heftigsten Bruchlinien verlief durch das Bildungs- und Hochschulwesen entlang der Frage, wie sich das übernatürliche Gebaren und die Ansichten der Kirche, die noch immer maßgeblich die Universitäten besetzten, mit der modernen Wissenschaft vereinbaren ließen. Liberale und katholische Studenten verachteten sich gegenseitig und krachten immer aneinander. Bis 1906 war Wahrmund Teil der Leo-Gesellschaft, die die Förderung der Wissenschaft auf katholischer Basis zum Ziel hatte, bevor er zum Obmann der Innsbrucker Ortsgruppe des Vereins Freie Schule wurde, der für eine komplette Entklerikalisierung des gesamten Bildungswesens eintrat. Vom Reformkatholiken wurde er zu einem Verfechter der kompletten Trennung von Kirche und Staat. Seine Vorlesungen erregten immer wieder die Aufmerksamkeit der Obrigkeit. Angeheizt von den Medien fand der Kulturkampf zwischen liberalen Deutschnationalisten, Konservativen, Christlichsozialen und Sozialdemokraten in der Person Ludwig Wahrmunds eine ideale Projektionsfläche. Was folgte waren Ausschreitungen, Streiks, Schlägereien zwischen Studentenverbindungen verschiedener Couleur und Ausrichtung und gegenseitige Diffamierungen unter Politikern. Die Los-von-Rom Bewegung des Deutschradikalen Georg Ritter von Schönerer (1842 – 1921) krachte auf der Bühne der Universität Innsbruck auf den politischen Katholizismus der Christlichsozialen. Die deutschnationalen Akademiker erhielten Unterstützung von den ebenfalls antiklerikalen Sozialdemokraten sowie von Bürgermeister Greil, auf konservativer Seite sprang die Tiroler Landesregierung ein. Die Wahrmund Affäre schaffte es als Kulturkampfdebatte bis in den Reichsrat. Für Christlichsoziale war es ein „Kampf des freissinnigen Judentums gegen das Christentum“ in dem sich „Zionisten, deutsche Kulturkämpfer, tschechische und ruthenische Radikale“ in einer „internationalen Koalition“ als „freisinniger Ring des jüdischen Radikalismus und des radikalen Slawentums“ präsentierten. Wahrmund hingegen bezeichnete in der allgemein aufgeheizten Stimmung katholische Studenten als „Verräter und Parasiten“. Als Wahrmund 1908 eine seiner Reden, in der er Gott, die christliche Moral und die katholische Heiligenverehrung anzweifelte, in Druck bringen ließ, erhielt er eine Anzeige wegen Gotteslästerung. Nach weiteren teils gewalttätigen Versammlungen sowohl auf konservativer und antiklerikaler Seite, studentischen Ausschreitungen und Streiks musste kurzzeitig sogar der Unibetrieb eingestellt werden. Wahrmund wurde zuerst beurlaubt, später an die deutsche Universität Prag versetzt.

Auch in der Ersten Republik war die Verbindung zwischen Kirche und Staat stark. Der christlichsoziale, als Eiserner Prälat in die Geschichte eingegangen Ignaz Seipel schaffte es in den 1920er Jahren bis ins höchste Amt des Staates. Bundeskanzler Engelbert Dollfuß sah seinen Ständestaat als Konstrukt auf katholischer Basis als Bollwerk gegen den Sozialismus. Auch nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg waren Kirche und Politik in Person von Bischof Rusch und Kanzler Wallnöfer ein Gespann. Erst dann begann eine ernsthafte Trennung. Glaube und Kirche haben noch immer ihren fixen Platz im Alltag der Innsbrucker, wenn auch oft unbemerkt. Die Kirchenaustritte der letzten Jahrzehnte haben der offiziellen Mitgliederzahl zwar eine Delle versetzt und Freizeitevents werden besser besucht als Sonntagsmessen. Die römisch-katholische Kirche besitzt aber noch immer viel Grund in und rund um Innsbruck, auch außerhalb der Mauern der jeweiligen Klöster und Ausbildungsstätten. Etliche Schulen in und rund um Innsbruck stehen ebenfalls unter dem Einfluss konservativer Kräfte und der Kirche. Und wer immer einen freien Feiertag genießt, ein Osterei ans andere peckt oder eine Kerze am Christbaum anzündet, muss nicht Christ sein, um als Tradition getarnt im Namen Jesu zu handeln.

A republic is born

Few eras are more difficult to grasp than the interwar period. The Roaring TwentiesJazz and automobiles come to mind, as do inflation and the economic crisis. In big cities like Berlin, young ladies behaved as Flappers mit Bubikopf, Zigarette und kurzen Röcken zu den neuen Klängen lasziv, Innsbrucks Bevölkerung gehörte als Teil der jungen Republik Österreich zum größten Teil zur Fraktion Armut, Wirtschaftskrise und politischer Polarisierung. Schon die Ausrufung der Republik am Parlament in Wien vor über 100.000 mehr oder minder begeisterten, vor allem aber verunsicherten Menschen verlief mit Tumulten, Schießereien, zwei Toten und 40 Verletzten alles andere als reibungsfrei. Wie es nach dem Ende der Monarchie und dem Wegfall eines großen Teils des Staatsterritoriums weitergehen sollte, wusste niemand. Das neue Österreich erschien zu klein und nicht lebensfähig. Der Beamtenstaat des k.u.k. Reiches setzte sich nahtlos unter neuer Fahne und Namen durch. Die Bundesländer als Nachfolger der alten Kronländer erhielten in der Verfassung im Rahmen des Föderalismus viel Spielraum in Gesetzgebung und Verwaltung. Die Begeisterung für den neuen Staat hielt sich aber in der Bevölkerung in Grenzen. Nicht nur, dass die Versorgungslage nach dem Wegfall des allergrößten Teils des ehemaligen Riesenreiches der Habsburger miserabel war, die Menschen misstrauten dem Grundgedanken der Republik. Die Monarchie war nicht perfekt gewesen, mit dem Gedanken von Demokratie konnten aber nur die allerwenigsten etwas anfangen. Anstatt Untertan des Kaisers war man nun zwar Bürger, allerdings nur Bürger eines Zwergstaates mit überdimensionierter und in den Bundesländern wenig geliebter Hauptstadt anstatt eines großen Reiches. In den ehemaligen Kronländern, die zum großen Teil christlich-sozial regiert wurden, sprach man gerne vom Viennese water headwho was fed by the yields of the industrious rural population.

Other federal states also toyed with the idea of seceding from the Republic after the plan to join Germany, which was supported by all parties, was prohibited by the victorious powers of the First World War. The Tyrolean plans, however, were particularly spectacular. From a neutral Alpine state with other federal states, a free state consisting of Tyrol and Bavaria or from Kufstein to Salurn, an annexation to Switzerland and even a Catholic church state under papal leadership, there were many ideas. The most obvious solution was particularly popular. In Tyrol, feeling German was nothing new. So why not align oneself politically with the big brother in the north? This desire was particularly pronounced among urban elites and students. The annexation to Germany was approved by 98% in a vote in Tyrol, but never materialised.

Instead of becoming part of Germany, they were subject to the unloved Wallschen. Italian troops occupied Innsbruck for almost two years after the end of the war. At the peace negotiations in Paris, the Brenner Pass was declared the new border. The historic Tyrol was divided in two. The military was stationed at the Brenner Pass to secure a border that had never existed before and was perceived as unnatural and unjust. In 1924, the Innsbruck municipal council decided to name squares and streets around the main railway station after South Tyrolean towns. Bozner Platz, Brixnerstrasse and Salurnerstrasse still bear their names today. Many people on both sides of the Brenner felt betrayed. Although the war was far from won, they did not see themselves as losers to Italy. Hatred of Italians reached its peak in the interwar period, even if the occupying troops were emphatically lenient. A passage from the short story collection "The front above the peaks" by the National Socialist author Karl Springenschmid from the 1930s reflects the general mood:

"The young girl says, 'Becoming Italian would be the worst thing.

Old Tappeiner just nods and grumbles: "I know it myself and we all know it: becoming a whale would be the worst thing."

Trouble also loomed in domestic politics. The revolution in Russia and the ensuing civil war with millions of deaths, expropriation and a complete reversal of the system cast its long shadow all the way to Austria. The prospect of Soviet conditions machte den Menschen Angst. Österreich war tief gespalten. Hauptstadt und Bundesländer, Stadt und Land, Bürger, Arbeiter und Bauern – im Vakuum der ersten Nachkriegsjahre wollte jede Gruppe die Zukunft nach ihren Vorstellungen gestalten. Die Kulturkämpfe der späten Monarchie zwischen Konservativen, Liberalen und Sozialisten setzte sich nahtlos fort. Die Kluft bestand nicht nur auf politischer Ebene. Moral, Familie, Freizeitgestaltung, Erziehung, Glaube, Rechtsverständnis – jeder Lebensbereich war betroffen. Wer sollte regieren? Wie sollten Vermögen, Rechte und Pflichten verteilt werden. Ein kommunistischer Umsturz war besonders in Tirol keine reale Gefahr, ließ sich aber medial gut als Bedrohung instrumentalisieren, um die Sozialdemokratie in Verruf zu bringen. 1919 hatte sich in Innsbruck zwar ein Workers', farmers' and soldiers' council nach sowjetischem Vorbild ausgerufen, sein Einfluss blieb aber gering und wurde von keiner Partei unterstützt. Ab 1920 bildeten sich offiziell sogenannten Soldatenräte, die aber christlich-sozial dominiert waren. Das bäuerliche und bürgerliche Lager rechts der Mitte militarisierte sich mit der Tiroler Heimatwehr professioneller und konnte sich über stärkeren Zulauf freuen als linke Gruppen, auch dank kirchlicher Unterstützung. Die Sozialdemokratie wurde von den Kirchkanzeln herab und in konservativen Medien als Jewish Party and homeless traitors to their country. They were all too readily blamed for the lost war and its consequences. The Tiroler Anzeiger summarised the people's fears in a nutshell: "Woe to the Christian people if the Jews=Socialists win the elections!".

With the new municipal council regulations of 1919, which provided for universal suffrage for all adults, the Innsbruck municipal council comprised 40 members. Of the 24,644 citizens called to the ballot box, an incredible 24,060 exercised their right to vote. Three women were already represented in the first municipal council with free elections. While in the rural districts the Tyrolean People's Party as a merger of Farmers' Union, People's Association und Catholic Labour Despite the strong headwinds in Innsbruck, the Social Democrats under the leadership of Martin Rapoldi were always able to win between 30 and 50% of the vote in the first elections in 1919. The fact that the Social Democrats did not succeed in winning the mayor's seat was due to the majorities in the municipal council formed by alliances with other parties. Liberals and Tyrolean People's Party was at least as hostile to social democracy as he was to the federal capital Vienna and the Italian occupiers.

But high politics was only the framework of the actual misery. The as Spanish flu This epidemic, which has gone down in history, also took its toll in Innsbruck in the years following the war. Exact figures were not recorded, but the number of deaths worldwide is estimated at 27 - 50 million. In Innsbruck, at the height of the Spanish flu epidemic, it is estimated that around 100 people fell victim to the disease every day. Many Innsbruck residents had not returned home from the battlefields and were missing as fathers, husbands and labourers. Many of those who had made it back were wounded and scarred by the horrors of war. As late as February 1920, the „Tyrolean Committee of the Siberians" im Gasthof Breinößl "...in favour of the fund for the repatriation of our prisoners of war..." organised a charity evening. Long after the war, the province of Tyrol still needed help from abroad to feed the population. Under the heading "Significant expansion of the American children's aid programme in Tyrol" was published on 9 April 1921 in the Innsbrucker Nachrichten to read: "Taking into account the needs of the province of Tyrol, the American representatives for Austria have most generously increased the daily number of meals to 18,000 portions.“

Then there was unemployment. Civil servants and public sector employees in particular lost their jobs after the League of Nations linked its loan to severe austerity measures. Salaries in the public sector were cut. There were repeated strikes. Tourism as an economic factor was non-existent due to the problems in the neighbouring countries, which were also shaken by the war. The construction industry, which had been booming before the war, collapsed completely. Innsbruck's largest company Huter & Söhne hatte 1913 über 700 Mitarbeiter, am Höhepunkt der Wirtschaftskrise 1933 waren es nur noch 18. Der Mittelstand brach zu einem guten Teil zusammen. Der durchschnittliche Innsbrucker war mittellos und mangelernährt. Oft konnten nicht mehr als 800 Kalorien pro Tag zusammengekratzt werden. Die Kriminalitätsrate war in diesem Klima der Armut höher als je zuvor. Viele Menschen verloren ihre Bleibe. 1922 waren in Innsbruck 3000 Familien auf Wohnungssuche trotz eines städtischen Notwohnungsprogrammes, das bereits mehrere Jahre in Kraft war. In alle verfügbaren Objekte wurden Wohnungen gebaut. Am 11. Februar 1921 fand sich in einer langen Liste in den Innsbrucker Nachrichten on the individual projects that were run, including this item:

„The municipal hospital abandoned the epidemic barracks in Pradl and made them available to the municipality for the construction of emergency flats. The necessary loan of 295 K (note: crowns) was approved for the construction of 7 emergency flats.“

Very little happened in the first few years. Then politics awoke from its lethargy. The crown, a relic from the monarchy, was replaced by the schilling as Austria's official currency on 1 January 1925. The old currency had lost more than 95% of its value against the dollar between 1918 and 1922, or the pre-war exchange rate. Innsbruck, like many other Austrian municipalities, began to print its own money. The amount of money in circulation rose from 12 billion crowns to over 3 trillion crowns between 1920 and 1922. The result was an epochal inflation.

With the currency reorganisation following the League of Nations loan under Chancellor Ignaz Seipel, not only banks and citizens picked themselves up, but public building contracts also increased again. Innsbruck modernised itself. There was what economists call a false boom. This short-lived economic recovery was a Bubble, However, the city of Innsbruck was awarded major projects such as the Tivoli, the municipal indoor swimming pool, the high road to the Hungerburg, the mountain railways to the Isel and the Nordkette, new schools and apartment blocks. The town bought Lake Achensee and, as the main shareholder of TIWAG, built the power station in Jenbach. The first airport was built in Reichenau in 1925, which also involved Innsbruck in air traffic 65 years after the opening of the railway line. In 1930, the university bridge connected the hospital in Wilten and the Höttinger Au. The Pembaur Bridge and the Prince Eugene Bridge were built on the River Sill. The signature of the new, large mass parties in the design of these projects cannot be overlooked.

The first republic was a difficult birth from the remnants of the former monarchy and it was not to last long. Despite the post-war problems, however, a lot of positive things also happened in the First Republic. Subjects became citizens. What began in the time of Maria Theresa was now continued under new auspices. The change from subject to citizen was characterised not only by a new right to vote, but above all by the increased care of the state. State regulations, schools, kindergartens, labour offices, hospitals and municipal housing estates replaced the benevolence of the landlord, sovereigns, wealthy citizens, the monarchy and the church.

To this day, much of the Austrian state and Innsbruck's cityscape and infrastructure are based on what emerged after the collapse of the monarchy. In Innsbruck, there are no conscious memorials to the emergence of the First Republic in Austria. The listed residential complexes such as the Slaughterhouse blockthe Pembaurblock or the Mandelsbergerblock oder die Pembaur School are contemporary witnesses turned to stone. Every year since 1925, World Savings Day has commemorated the introduction of the schilling. Children and adults should be educated to handle money responsibly.

The year 1848 and its consequences

The year 1848 occupies a mythical place in European history. Although the hotspots were not to be found in secluded Tyrol, but in the major metropolises such as Paris, Vienna, Budapest, Milan and Berlin, even in the Holy Land however, the revolutionary year left its mark. In contrast to the rural surroundings, an enlightened educated middle class had developed in Innsbruck. Enlightened people no longer wanted to be subjects of a monarch or sovereign, but citizens with rights and duties towards the state. Students and freelancers demanded political participation, freedom of the press and civil rights. Workers demanded better wages and working conditions. Radical liberals and nationalists in particular even questioned the omnipotence of the church.

In March 1848, this socially and politically highly explosive mixture erupted in riots in many European cities. In Innsbruck, students and professors celebrated the newly enacted freedom of the press with a torchlight procession. On the whole, however, the revolution proceeded calmly in the leisurely Tyrol. It would be foolhardy to speak of a spontaneous outburst of emotion; the date of the procession was postponed from 20 to 21 March due to bad weather. There were hardly any anti-Habsburg riots or attacks; a stray stone thrown into a Jesuit window was one of the highlights of the Alpine version of the 1848 revolution. The students even helped the city magistrate to monitor public order in order to show their gratitude to the monarch for the newly granted freedoms and their loyalty.

The initial enthusiasm for bourgeois revolution was quickly replaced by German nationalist, patriotic fervour in Innsbruck. On 6 April 1848, the German flag was waved by the governor of Tyrol during a ceremonial procession. A German flag was also raised on the city tower. Tricolour was hoisted. While students, workers, liberal-nationalist-minded citizens, republicans, supporters of a constitutional monarchy and Catholic conservatives disagreed on social issues such as freedom of the press, they shared a dislike of the Italian independence movement that had spread from Piedmont and Milan to northern Italy. Innsbruck students and marksmen marched to Trentino with the support of the k.k. The Innsbruck students and riflemen moved into Trentino to nip the unrest and uprisings in the bud. Well-known members of this corps were Father Haspinger, who had already fought with Andreas Hofer in 1809, and Adolf Pichler. Johann Nepomuk Mahl-Schedl, wealthy owner of Büchsenhausen Castle, even equipped his own company with which he marched across the Brenner Pass to secure the border.

The city of Innsbruck, as the political and economic centre of the multinational crown land of Tyrol and home to many Italian speakers, also became the arena of this nationality conflict. Combined with copious amounts of alcohol, anti-Italian sentiment in Innsbruck posed more of a threat to public order than civil liberties. A quarrel between a German-speaking craftsman and an Italian-speaking Ladin got so heated that it almost led to a pogrom against the numerous businesses and restaurants owned by Italian-speaking Tyroleans.

The relative tranquillity of Innsbruck suited the imperial house, which was under pressure. When things did not stop boiling in Vienna even after March, Emperor Ferdinand fled to Tyrol in May. According to press reports from this time, he was received enthusiastically by the population.

"Wie heißt das Land, dem solche Ehre zu Theil wird, wer ist das Volk, das ein solches Vertrauen genießt in dieser verhängnißvollen Zeit? Stützt sich die Ruhe und Sicherheit hier bloß auf die Sage aus alter Zeit, oder liegt auch in der Gegenwart ein Grund, auf dem man bauen kann, den der Wind nicht weg bläst, und der Sturm nicht erschüttert? Dieses Alipenland heißt Tirol, gefällts dir wohl? Ja, das tirolische Volk allein bewährt in der Mitte des aufgewühlten Europa die Ehrfurcht und Treue, den Muth und die Kraft für sein angestammtes Regentenhaus, während ringsum Auflehnung, Widerspruch. Trotz und Forderung, häufig sogar Aufruhr und Umsturz toben; Tirol allein hält fest ohne Wanken an Sitte und Gehorsam, auf Religion, Wahrheit und Recht, während anderwärts die Frechheit und Lüge, der Wahnsinn und die Leidenschaften herrschen anstatt folgen wollen. Und während im großen Kaiserreiche sich die Bande überall lockern, oder gar zu lösen drohen; wo die Willkühr, von den Begierden getrieben, Gesetze umstürzt, offenen Aufruhr predigt, täglich mit neuen Forderungen losgeht; eigenmächtig ephemere- wie das Wetter wechselnde Einrichtungen schafft; während Wien, die alte sonst so friedliche Kaiserstadt, sich von der erhitzten Phantasie der Jugend lenken und gängeln läßt, und die Räthe des Reichs auf eine schmähliche Weise behandelt, nach Laune beliebig, und mit jakobinischer Anmaßung, über alle Provinzen verfügend, absetzt und anstellt, ja sogar ohne Ehrfurcht, den Kaiaer mit Sturm-Petitionen verfolgt; während jetzt von allen Seiten her Deputationen mit Ergebenheits-Addressen mit Bittgesuchen und Loyalitätsversicherungen dem Kaiser nach Innsbruck folgen, steht Tirol ganz ruhig, gleich einer stillen Insel, mitten im brausenden Meeressturme, und des kleinen Völkchens treue Brust bildet, wie seine Berge und Felsen, eine feste Mauer in Gesetz und Ordnung, für den Kaiser und das Vaterland."

In June, a young Franz Josef, not yet emperor at the time, also stayed at the Hofburg on his way back from the battlefields of northern Italy instead of travelling directly to Vienna. Innsbruck was once again the royal seat, if only for one summer. While blood was flowing in Vienna, Milan and Budapest, the imperial family enjoyed life in the Tyrolean countryside. Ferdinand, Franz Karl, his wife Sophie and Franz Josef received guests from foreign royal courts and were chauffeured in four-in-hand carriages to the region's excursion destinations such as Weiherburg Castle, Stefansbrücke Bridge, Kranebitten and high up to Heiligwasser. A little later, however, the cosy atmosphere came to an end. Under gentle pressure, Ferdinand, who was no longer considered fit for office, passed the torch of regency to Franz Josef I. In July 1848, the first parliamentary session was held in the Court Riding School in Vienna. The first constitution was enacted. However, the monarchy's desire for reform quickly waned. The new parliament was an imperial council, it could not pass any binding laws, the emperor never attended it during his lifetime and did not understand why the Danube Monarchy, as a divinely appointed monarchy, needed this council.

Nevertheless, the liberalisation that had been gently set in motion took its course in the cities. Innsbruck was given the status of a town with its own statute. Innsbruck's municipal law provided for a right of citizenship that was linked to ownership or the payment of taxes, but legally guaranteed certain rights to members of the community. Birthright citizenship could be acquired by birth, marriage or extraordinary conferment and at least gave male adults the right to vote at municipal level. If you got into financial difficulties, you had the right to basic support from the town.

Thanks to the census-based majority voting system, the Greater German liberal faction prevailed within the city government, in which merchants, tradesmen, industrialists and innkeepers set the tone. On 2 June 1848, the first edition of the liberal and Greater German-minded Innsbrucker Zeitungfrom which the above article on the emperor's arrival in Innsbruck is taken. Conservatives, on the other hand, read the Volksblatt for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. Moderate readers who favoured a constitutional monarchy preferred to consume the Bothen for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. However, the freedom of the press soon came to an end. The previously abolished censorship was reintroduced in parts. Newspaper publishers had to undergo some harassment by the authorities. Newspapers were not allowed to write against the state government, monarchy or church.

"Anyone who, by means of printed matter, incites, instigates or attempts to incite others to take action which would bring about the violent separation of a part from the unified state... of the Austrian Empire... or the general Austrian Imperial Diet or the provincial assemblies of the individual crown lands.... Imperial Diet or the Diet of the individual Crown Lands... violently disrupts... shall be punished with severe imprisonment of two to ten years."

After Innsbruck officially replaced Meran as the provincial capital in 1849 and thus finally became the political centre of Tyrol, political parties were formed. From 1868, the liberal and Greater German orientated party provided the mayor of the city of Innsbruck. The influence of the church declined in Innsbruck in contrast to the surrounding communities. Individualism, capitalism, nationalism and consumerism stepped into the breach. New worlds of work, department stores, theatres, cafés and dance halls did not supplant religion in the city either, but the emphasis changed as a result of the civil liberties won in 1848.

Perhaps the most important change to the law was the Basic relief patent. In Innsbruck, the clergy, above all Wilten Abbey, held a large proportion of the peasant land. The church and nobility were not subject to taxation. In 1848/49, manorial rule and servitude were abolished in Austria. Land rents, tithes and roboters were thus abolished. The landlords received one third of the value of their land from the state as part of the land relief, one third was regarded as tax relief and the farmers had to pay one third of the relief themselves. They could pay off this amount in instalments over a period of twenty years.

The after-effects can still be felt today. The descendants of the then successful farmers enjoy the fruits of prosperity through inherited land ownership, which can be traced back to the land relief of 1848, as well as political influence through land sales for housing construction, leases and public sector redemptions for infrastructure projects. The land-owning nobles of the past had to resign themselves to the ignominy of pursuing middle-class labour. The transition from birthright to privileged status within society was often successful thanks to financial means, networks and education. Many of Innsbruck's academic dynasties began in the decades after 1848.

Das bis dato unbekannte Phänomen der Freizeit kam, wenn auch für den größten Teil nur spärlich, auf und begünstigte gemeinsam mit frei verfügbarem Einkommen einer größeren Anzahl an Menschen Hobbies. Zivile Organisationen und Vereine, vom Lesezirkel über Sängerbünde, Feuerwehren und Sportvereine, gründeten sich. Auch im Stadtbild manifestierte sich das Revolutionsjahr. Parks wie der Englische Garten beim Schloss Ambras oder der Hofgarten waren nicht mehr exklusiv der Aristokratie vorbehalten, sondern dienten den Bürgern als Naherholungsgebiete vom beengten Dasein. In St. Nikolaus entstand der Waltherpark als kleine Ruheoase. Einen Stock höher eröffnete im Schloss Büchsenhausen Tirols erste Schwimm- und Badeanstalt, wenig später folgte ein weiteres Bad in Dreiheiligen. Ausflugsgasthöfe rund um Innsbruck florierten. Neben den gehobenen Restaurants und Hotels entstand eine Szene aus Gastwirtschaften, in denen sich auch Arbeiter und Angestellte gemütliche Abende bei Theater, Musik und Tanz leisten konnten.

Wilhelm Greil: DER Bürgermeister Innsbrucks

One of the most important figures in the town's history was Wilhelm Greil (1850 - 1923). From 1896 to 1923, the entrepreneur held the office of mayor, having previously helped to shape the city's fortunes as deputy mayor. It was a time of growth, the incorporation of entire neighbourhoods, technical innovations and new media. The four decades between the economic crisis of 1873 and the First World War were characterised by unprecedented economic growth and rapid modernisation. Private investment in infrastructure such as railways, energy and electricity was desired by the state and favoured by tax breaks in order to lead the countries and cities of the ailing Danube monarchy into the modern age. The city's economy boomed. Businesses sprang up in the new districts of Pradl and Wilten, attracting workers. Tourism also brought fresh capital into the city. At the same time, however, the concentration of people in a confined space under sometimes precarious hygiene conditions also brought problems. The outskirts of the city and the neighbouring villages in particular were regularly plagued by typhus.

Innsbruck city politics, in which Greil was active, was characterised by the struggle between liberal and conservative forces. Greil belonged to the "Deutschen Volkspartei", a liberal and national-Great German party. What appears to be a contradiction today, liberal and national, was a politically common and well-functioning pair of ideas in the 19th century. The Pan-Germanism was not a political peculiarity of a radical right-wing minority, but rather a centrist trend, particularly in German-speaking cities in the Reich, which was significant in various forms across almost all parties until after the Second World War. Innsbruckers who were self-respecting did not describe themselves as Austrians, but as Germans. Those who were members of the liberal Innsbrucker Nachrichten of the period around the turn of the century, you will find countless articles in which the common ground between the German Empire and the German-speaking countries was made the topic of the day, while distancing themselves from other ethnic groups within the multinational Habsburg Empire. Greil was a skilful politician who operated within the predetermined power structures of his time. He knew how to skilfully manoeuvre around the traditional powers, the monarchy and the clergy and to come to terms with them.

Taxes, social policy, education, housing and the design of public spaces were discussed with passion and fervour. Due to an electoral system based on voting rights via property classes, only around 10% of the entire population of Innsbruck were able to go to the ballot box. Women were excluded as a matter of principle. Relative suffrage applied within the three electoral bodies, which meant as much as: The winner takes it all. Greil wohne passenderweise ähnlich wie ein Renaissancefürst. Er entstammte der großbürgerlichen Upper Class. Sein Vater konnte es sich leisten, im Palais Lodron in der Maria-Theresienstraße die Homebase der Familie zu gründen. Massenparteien wie die Sozialdemokratie konnten sich bis zur Wahlrechtsreform der Ersten Republik nicht durchsetzen. Konservative hatten es in Innsbruck auf Grund der Bevölkerungszusammensetzung, besonders bis zur Eingemeindung von Wilten und Pradl, ebenfalls schwer. Bürgermeister Greil konnte auf 100% Rückhalt im Gemeinderat bauen, was die Entscheidungsfindung und Lenkung natürlich erheblich vereinfachte. Bei aller Effizienz, die Innsbrucker Bürgermeister bei oberflächlicher Betrachtung an den Tag legten, sollte man nicht vergessen, dass das nur möglich war, weil sie als Teil einer Elite aus Unternehmern, Handelstreibenden und Freiberuflern ohne nennenswerte Opposition und Rücksichtnahme auf andere Bevölkerungsgruppen wie Arbeitern, Handwerkern und Angestellten in einer Art gewählten Diktatur durchregierten. Das Reichsgemeindegesetz von 1862 verlieh Städten wie Innsbruck und damit den Bürgermeistern größere Befugnisse. Es verwundert kaum, dass die Amtskette, die Greil zu seinem 60. Geburtstag von seinen Kollegen im Gemeinderat verliehen bekam, den Ordensketten des alten Adels erstaunlich ähnelte.

Under Greil's aegis and the general economic upturn, fuelled by private investment, Innsbruck expanded at a rapid pace. In true merchant style, the municipal council purchased land with foresight in order to enable the city to innovate. The politician Greil was able to rely on the civil servants and town planners Eduard Klingler, Jakob Albert and Theodor Prachensky for the major building projects of the time. Infrastructure projects such as the new town hall in Maria-Theresienstraße in 1897, the opening of the Mittelgebirgsbahn railway, the Hungerburgbahn and the Karwendelbahn wurden während seiner Regierungszeit umgesetzt. Weitere gut sichtbare Meilensteine waren die Erneuerung des Marktplatzes und der Bau der Markthalle. Neben den prestigeträchtigen Großprojekten entstanden in den letzten Jahrzehnten des 19. Jahrhunderts aber viele unauffällige Revolutionen. Vieles, was in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts vorangetrieben wurde, gehört heute zum Alltag. Für die Menschen dieser Zeit waren diese Dinge aber eine echte Sensation und lebensverändernd. Bereits Greils Vorgänger Bürgermeister Heinrich Falk (1840 – 1917) hatte erheblich zur Modernisierung der Stadt und zur Besiedelung des Saggen beigetragen. Seit 1859 war die Beleuchtung der Stadt mit Gasrohrleitungen stetig vorangeschritten. Mit dem Wachstum der Stadt und der Modernisierung wurden die Senkgruben, die in Hinterhöfen der Häuser als Abort dienten und nach Entleerung an umliegende Landwirte als Dünger verkauft wurden, zu einer Unzumutbarkeit für immer mehr Menschen. 1880 wurde das RaggingThe city was responsible for the emptying of the lavatories. Two pneumatic machines were to make the process at least a little more hygienic. Between 1887 and 1891, Innsbruck was equipped with a modern high-pressure water pipeline, which could also be used to supply fresh water to flats on higher floors. For those who could afford it, this was the first opportunity to install a flush toilet in their own home.

Greil continued this campaign of modernisation. After decades of discussions, the construction of a modern alluvial sewerage system began in 1903. Starting in the city centre, more and more districts were connected to this now commonplace luxury. By 1908, only the Koatlackler Mariahilf und St. Nikolaus nicht an das Kanalsystem angeschlossen. Auch der neue Schlachthof im Saggen erhöhte Hygiene und Sauberkeit in der Stadt. Schlecht kontrollierte Hofschlachtungen gehörten mit wenigen Ausnahmen der Vergangenheit an. Das Vieh kam im Zug am Sillspitz an und wurde in der modernen Anlage fachgerecht geschlachtet. Greil überführte auch das Gaswerk in Pradl und das Elektrizitätswerk in Mühlau in städtischen Besitz. Die Straßenbeleuchtung wurde im 20. Jahrhundert von den Gaslaternen auf elektrisches Licht umgestellt. 1888 übersiedelte das Krankenhaus von der Maria-Theresienstraße an seinen heutigen Standort. Bürgermeister und Gemeinderat konnten sich bei dieser Innsbrucker Renaissance neben der wachsenden Wirtschaftskraft in der Vorkriegszeit auch auf Mäzen aus dem Bürgertum stützen. Waren technische Neuerungen und Infrastruktur Sache der Liberalen, verblieb die Fürsorge der Ärmsten weiterhin bei klerikal gesinnten Kräften, wenn auch nicht mehr bei der Kirche selbst. Freiherr Johann von Sieberer stiftete das Greisenasyl und das Waisenhaus im Saggen. Leonhard Lang stiftete das Gebäude in der Maria-Theresienstraße, in der sich bis heute das Rathaus befindet gegen das Versprechen der Stadt ein Lehrlingsheim zu bauen.

Im Gegensatz zur boomenden Vorkriegsära war die Zeit nach 1914 vom Krisenmanagement geprägt. In seinen letzten Amtsjahren begleitete Greil Innsbruck am Übergang von der Habsburgermonarchie zur Republik durch Jahre, die vor allem durch Hunger, Elend, Mittelknappheit und Unsicherheit geprägt waren. Er war 68 Jahre alt, als italienische Truppen nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg die Stadt besetzten und Tirol am Brenner geteilt wurde. Das Ende der Monarchie und des Zensuswahlrechts bedeuteten auch den Niedergang der Liberalen in Innsbruck, auch wenn Greil das in seiner aktiven Karriere nur teilweise miterlebte. 1919 konnten die Sozialdemokraten in Innsbruck zwar zum ersten Mal den Wahlsieg davontragen, dank der Mehrheiten im Gemeinderat blieb Greil aber Bürgermeister. 1928 verstarb er als Ehrenbürger der Stadt Innsbruck im Alter von 78 Jahren. Die Wilhelm-Greil-Straße war noch zu seinen Lebzeiten nach ihm benannt worden.

The Rapoldis: hydropower and resistance

The couple Martin (1880 - 1926) and Maria Rapoldi (1884 - 1975) were among the most impressive personalities in Innsbruck city politics from the end of the monarchy to the post-war period. Martin Rapoldi came to Innsbruck via Carinthia, Vienna and Bohemia. He first came into contact with socially critical ideas during his carpentry apprenticeship. Together with other apprentices, he founded a kind of anarchist trade union in Klagenfurt with youthful fervour. In the capital of the Danube Monarchy and in Zatek in what is now the Czech Republic, he became involved in the trade union and the recently officially founded Social Democratic Party. In 1904, he moved to Innsbruck, where the man in his mid-twenties soon attracted attention as an ambitious organiser and rousing speaker. The following year, he married his wife Maria, who was also politically active. Thanks to his linguistic talent, he took over the Volkszeitungthe press organ of the Tyrolean Social Democrats. Despite initial euphoria in favour of entering the war, including on the part of the Social Democrats, the anti-clerical Pfaffenfresser Rapoldi soon came out in favour of peace and the introduction of universal suffrage at municipal level. After 1918, he was completely in line with the party line and in favour of unification with the German Reich.

In the early years of the First Republic, he had a short but stellar career. He was elected a member of the provincial parliament in Tyrol and a member of the first National Council in Vienna. In Innsbruck, he managed to make the Social Democrats the strongest party in the local council. However, due to the anti-socialist stance of the other parliamentary groups in the municipal council, he was never able to fill the position of mayor. Housing construction and the municipal energy supply were of particular concern to him. During Rapoldi's time on the municipal council, the major projects Schlachthofblock and Pembaurblock were built in Dreiheiligen and Pradl, as well as the school and kindergarten in today's Pembaurstraße. He was instrumental in the construction of the Innsbrucker Lichtwerke, today's Innsbrucker Kommunalbetriebe, was involved. His greatest achievement, however, was the acquisition of Lake Achensee. As early as 1911, the city of Innsbruck under Wilhelm Greil negotiated with the Bavarian monastery of Fiecht to purchase the lake for a power station for the city of Innsbruck's electricity plant. The war interrupted the project. In 1919, negotiations between the local council and the monastery about the purchase of Lake Achensee began anew. The purchase price was finally set at 1.2 million crowns plus the monastery's own electricity requirements. Financing proved difficult in the difficult post-war period. Until 1924, the federal government granted tax relief to municipalities for the construction of hydroelectric power plants. At the last minute, TIWAG, Tiroler Wasserkraft AG, was founded with the city of Innsbruck as the majority owner and the purchase was finalised. Legend has it that due to inflation between 1919 and 1924, it was not possible to buy a lake for the value of the purchase price at the time of payment, but only a man's suit. When the town sold the lake to TIWAG 60 years later, almost a billion schillings was realised, enough to pay off the town's debts. Martin Rapoldi was the driving force behind the construction of the Achensee railway, the Achensee power plant and the founding of Tiroler Wasserkraft TIWAG. In 1926, the enterprising Red journeyman carpenter at the young age of 46 from the consequences of kidney inflammation.

The life of his wife Maria is no less impressive. She came into contact with social democratic ideas at an early age in her parents' household in Wörgl. A trained accountant, she moved to Innsbruck. She probably met her future husband while working for the health insurance company. Despite having two small daughters, Maria was already involved in the regional women's conference of the Social Democrats in 1912. After the death of her husband, she remained active in social democracy. As an employee of the Volkszeitung During the years of Austrofascism, it was repeatedly targeted by the Vaterländischen Front. After the Volkszeitung was banned by the regime as part of the censorship programme, she had to eke out a living as an unemployed widow. She opened a stamp shop in the historic city centre. At the same time, she worked underground at the Red AidShe was also involved in supporting the families of imprisoned members of the Republican Protection League. During the National Socialist era, she was imprisoned for a short time. After the war, she also stepped out of the shadow of her husband Martin, who died young, in an official capacity. From 1946 to 1959, she was a member of Innsbruck's municipal council. She campaigned for social agendas such as old people's homes, children's homes and the improvement of food and health care in the post-war period. As a member of the Tyrolean relief organisation, the city school board, the board of trustees of the Sieberer orphanage and the administrative committee of the Innsbruck secondary school for girls

Martin and Maria Rapoldi are buried in a grave of honour at the Westfriedhof cemetery. The park in Pradl, opened in 1927, also bears the names of the two memorable city politicians. In Kranebitten, the Social Democratic Party erected a monument to him after Martin's early death, which was destroyed by members of the Home Army in 1934.