Annasäule

Maria-Theresienstrasse 31

Worth knowing

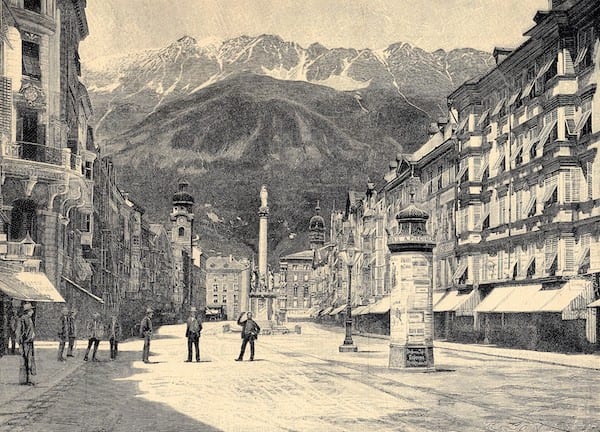

The Annasäule (St. Anne’s Column) is one of Innsbruck’s most popular photo spots. Especially in winter, when the snow-covered Nordkette mountain range rises behind the Old Town, the column against the backdrop of the mountains becomes a true hotspot—not just for professional influencers. The Annasäule was erected to commemorate the end of a conflict between Tyrol and Bavaria, which went down in history as the “Boarischer Rummel” (Bavarian turmoil). In June 1703, the Bavarian Elector Max Emanuel crossed the border with an army of 12,000 men and captured the supposedly impregnable fortress of Kufstein. After a series of victories, he advanced to Innsbruck and occupied the city. Gradually, Tyrolean troops managed to regroup and celebrate their first victories. On July 26, St. Anne’s Day, Tyrol’s defenders succeeded in driving the Bavarian invaders out of Innsbruck. To commemorate this victory, the Tyrolean Estates decided to erect a monument dedicated to St. Anne, to protect the city from future wars. The monument features several figures symbolically important to Innsbruck’s citizens at the time. The statue of St. Anne, its namesake, gazes devoutly north toward Bavaria. She was chosen not only because the victory occurred on her feast day. Anne was the mother of Mary, and her wish for a child was fulfilled very late by God. She is considered the patron saint of expectant mothers and the childless. Her domestic diligence and maternal role in stabilizing the household were regarded as feminine virtues before the first, very delicate wave of female emancipation in conservative Tyrol. St. George, the combative dragon slayer and patron saint of Tyrol, is also represented on the Annasäule. Statues of Cassian, patron of the Diocese of Brixen (South Tyrol), and Vigilius, patron of the Diocese of Trent (Trentino), flank the saints. Until 1964, Innsbruck was not the episcopal seat of the region. In 1706, the year the monument was built, Tyrol was ecclesiastically governed by the bishops of Brixen and Trent. This is why the two saints of these dioceses are present in Innsbruck. Particularly striking is the popular Tyrolean depiction of the Madonna on the crescent moon, which crowns the ensemble. In the apocalyptic Revelation of John, she is described as a witness to the final battle between Archangel Michael and the devil: “A woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head.” She can be interpreted as a symbol of the struggle between good and evil, which, according to Tyrolean interpretation, played out repeatedly in Innsbruck’s history during conflicts between the Habsburgs and the Wittelsbachs. The Annasäule quickly became a place of remembrance in Innsbruck. People gathered here to celebrate, debate, worry, and protest. Since 1945, Innsbruck has been spared from war, but the square around the Annasäule is still often a battleground—albeit on a different level. Local café and bar owners dislike when young people sit on the monument’s steps to enjoy the city center’s atmosphere without spending money. Yet the square is popular not only with ice cream lovers and beer drinkers but also as a venue for demonstrations and rallies of all kinds.

Der Boarische Rummel und der Spanische Erbfolgekrieg

When Charles II of Spain, the last Habsburg of the Spanish line, left the throne without an heir in 1700, the War of the Spanish Succession between the world powers. The Habsburgs, French and Bavarians each tried to bring their candidate to the throne. In changing alliances around the globe, large armies faced each other in the coalition wars. Through frequently changing alliances between Europe, Asia and America, the Dutch, Great Britain - and even Sweden and Russia - were also involved. But what does this have to do with Innsbruck?

In 1703, the Electorate of Bavaria, allied with France, laid claim to the County of Tyrol. Sigismund Franz, the last prince of the Tyrolean line, died in 1665. Since then, Tyrol has been governed by governors. The low and easy-to-cross Alpine passes made the land strategically important in this global conflict between the Great Powers. In order to underpin their supposed claim to Tyrol militarily, the Bavarians marched with 12,000 men via Kufstein into the Inn Valley. They were quickly able to conquer the area around Innsbruck in order to unite with the troops of their French ally, who were marching from Italy towards Tyrol.

South Tyrolean and Upper Inn Valley troops, largely recruited from the rifle clubs, successfully stood up to the foreign powers. Troops from Innsbruck marched out into the lowlands to offer resistance to the enemy troops. 400 students and grammar school pupils volunteered to take up arms and were placed under the command of Baron von Cles in front of the Mariahilfkirche church. As good Catholics, the Tyroleans swore allegiance to the heart of Jesus and asked for heavenly assistance. Together with the signal fires that were lit on the mountains to communicate between the troops, this custom is still celebrated every year in June as the Mountain fire continued. In a battle at the Pontlatzer Bridge near Landeck, the Tyrolean troops were able to celebrate a success that turned the tide. In guerrilla warfare in rough terrain, the outnumbered Tyrolean marksmen were on a par with the large armies, which were trained and equipped for field battles. They skilfully exploited their superior local knowledge and sniping skills. It was not until later that regular Habsburg troops from South Tyrol joined them. Thus, on 26 July, St. Anne's Day, the Bavarian foreign rule was driven out of Innsbruck again. The interesting thing is that Elector Max Emanuel was not greeted with hostility by a large proportion of the citizens of Innsbruck, but rather with enthusiasm. The Boarische Rummel showed how different the political ideas of the urban and rural population in Tyrol were.

The Boarische Rummel, wie der kurze Kampf um Tirol genannt wurde, klingt nur oberflächlich nach einem Scharmützel. 1704 kam es in der Schlacht von Höchstädt zu einer bayrischen Niederlage gegen die Habsburger. In der Folge besetzten österreichische Truppen München besetzen. Nun war es andersherum, die Bayern erhoben sich gegen die Habsburger. Unter anderem kam es dabei zur bekannten Sendlinger Mordweihnacht, in which Habsburg troops massacred around 1000 soldiers who had actually already surrendered. The complicated relationship between the Habsburgs, Tyroleans, Innsbruckers and Bavarians was a phenomenon that continued to haunt the country. The Tyrolean peasants accused official Austria, not without justification, of neglecting national defence. In a wave of anger and hatred towards all those who had not defended themselves against the Bavarians and the French, violence also spilled over into institutions such as Wilten Abbey, where the Bavarians had taken up quarters.

Innsbruck and the House of Habsburg

Today, Innsbruck's city centre is characterised by buildings and monuments that commemorate the Habsburg family. For many centuries, the Habsburgs were a European ruling dynasty whose sphere of influence included a wide variety of territories. At the zenith of their power, they were the rulers of a "Reich, in dem die Sonne nie untergeht". Through wars and skilful marriage and power politics, they sat at the levers of power between South America and the Ukraine in various eras. Innsbruck was repeatedly the centre of power for this dynasty. The relationship was particularly intense between the 15th and 17th centuries. Due to its strategically favourable location between the Italian cities and German centres such as Augsburg and Regensburg, Innsbruck was given a special place in the empire at the latest after its elevation to a royal seat under Emperor Maximilian.

Tyrol was a province and, as a conservative region, usually favoured the dynasty. Even after its time as a royal seat, the birth of new children of the ruling family was celebrated with parades and processions, deaths were mourned in memorial masses and archdukes, kings and emperors were immortalised in public spaces with statues and pictures. The Habsburgs also valued the loyalty of their Alpine subjects to the Nibelung. In the 19th century, the Jesuit Hartmann Grisar wrote the following about the celebrations to mark the birth of Archduke Leopold in 1716:

„But what an imposing sight it was when, as night fell, the Abbot of Wilten held the final religious function in front of St Anne's Column, which had been consecrated by the blood of the country, surrounded by rows of students and the packed crowd; when, by the light of thousands of burning lights and torches, the whole town, together with the studying youth, the hope of the country, implored heaven for a blessing for the Emperor's newborn first son.“

Its inaccessible location made it the perfect refuge in troubled and crisis-ridden times. Charles V (1500 - 1558) fled during a conflict with the Protestant Schmalkaldischen Bund to Innsbruck for some time. Ferdinand I (1793 - 1875) allowed his family to stay in Innsbruck, far away from the Ottoman threat in eastern Austria. Shortly before his coronation in the turbulent summer of the 1848 revolution, Franz Josef I enjoyed the seclusion of Innsbruck together with his brother Maximilian, who was later shot by insurgent nationalists as Emperor of Mexico. A plaque at the Alpengasthof Heiligwasser above Igls reminds us that the monarch spent the night here as part of his ascent of the Patscherkofel. Some of the Tyrolean sovereigns from the House of Habsburg had no special relationship with Tyrol, nor did they have any particular affection for this German land. Ferdinand I (1503 - 1564) was educated at the Spanish court. Maximilian's grandson Charles V had grown up in Burgundy. When he set foot on Spanish soil for the first time at the age of 17 to take over his mother Joan's inheritance of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, he did not speak a word of Spanish. When he was elected German Emperor in 1519, he did not speak a word of German.

Not all Habsburgs were happy to be „allowed“ to be in Innsbruck. Married princes and princesses such as Maximilian's second wife Bianca Maria Sforza or Ferdinand II's second wife Anna Caterina Gonzaga were stranded in the harsh, German-speaking mountains after the wedding without being asked. If you also imagine what a move and marriage from Italy to Tyrol to a foreign man meant for a teenager, you can imagine how difficult life was for the princesses. Until the 20th century, children of the aristocracy were primarily brought up to be politically married. There was no opposition to this. One might imagine courtly life to be ostentatious, but privacy was not provided for in all this luxury.

Innsbruck experienced its Habsburg heyday when the city was the main residence of the Tyrolean sovereigns. Ferdinand II, Maximilian III and Leopold V and their wives left their mark on the city during their reigns. When Sigismund Franz von Habsburg (1630 - 1665) died childless as the last sovereign prince, the title of residence city was also history and Tyrol was ruled by a governor. Tyrolean mining had lost its importance and did not require any special attention. Shortly afterwards, the Habsburgs lost their possessions in Western Europe along with Spain and Burgundy, which moved Innsbruck from the centre to the periphery of the empire. In the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy of the 19th century, Innsbruck was the western outpost of a huge empire that stretched as far as today's Ukraine. Franz Josef I (1830 - 1916) ruled over a multi-ethnic empire between 1848 and 1916. However, his neo-absolutist concept of rule was out of date. Although Austria had had a parliament and a constitution since 1867, the emperor regarded this government as "his". Ministers were responsible to the emperor, who was above the government. In the second half of the 19th century, the ailing empire collapsed. On 28 October 1918, the Republic of Czechoslovakia was proclaimed, and on 29 October, Croats, Slovenes and Serbs left the monarchy. The last Emperor Charles abdicated on 11 November. On 12 November, "Deutschösterreich zur demokratischen Republik, in der alle Gewalt vom Volke ausgeht“. The chapter of the Habsburgs was over.

Despite all the national, economic and democratic problems that existed in the multi-ethnic states that were subject to the Habsburgs in various compositions and forms, the subsequent nation states were sometimes much less successful in reconciling the interests of minorities and cultural differences within their territories. Since the eastward enlargement of the EU, the Habsburg monarchy has been seen by some well-meaning historians as a pre-modern predecessor of the European Union. Together with the Catholic Church, the Habsburgs shaped the public sphere through architecture, art and culture. Goldenes DachlThe Hofburg, the Triumphal Gate, Ambras Castle, the Leopold Fountain and many other buildings still remind us of the presence of the most important ruling dynasty in European history in Innsbruck.

Believe, Church and Power

Die Fülle an Kirchen, Kapellen, Kruzifixen und Wandmalereien im öffentlichen Raum wirkt auf viele Besucher Innsbrucks aus anderen Ländern eigenartig. Nicht nur Gotteshäuser, auch viele Privathäuser sind mit Darstellungen der Heiligen Familie oder biblischen Szenen geschmückt. Der christliche Glaube und seine Institutionen waren in ganz Europa über Jahrhunderte alltagsbestimmend. Innsbruck als Residenzstadt der streng katholischen Habsburger und Hauptstadt des selbsternannten Heiligen Landes Tirol wurde bei der Ausstattung mit kirchlichen Bauwerkern besonders beglückt. Allein die Dimension der Kirchen umgelegt auf die Verhältnisse vergangener Zeiten sind gigantisch. Die Stadt mit ihren knapp 5000 Einwohnern besaß im 16. Jahrhundert mehrere Kirchen, die in Pracht und Größe jedes andere Gebäude überstrahlte, auch die Paläste der Aristokratie. Das Kloster Wilten war ein Riesenkomplex inmitten eines kleinen Bauerndorfes, das sich darum gruppierte. Die räumlichen Ausmaße der Gotteshäuser spiegelt die Bedeutung im politischen und sozialen Gefüge wider.

Die Kirche war für viele Innsbrucker nicht nur moralische Instanz, sondern auch weltlicher Grundherr. Der Bischof von Brixen war formal hierarchisch dem Landesfürsten gleichgestellt. Die Bauern arbeiteten auf den Landgütern des Bischofs wie sie auf den Landgütern eines weltlichen Fürsten für diesen arbeiteten. Damit hatte sie die Steuer- und Rechtshoheit über viele Menschen. Die kirchlichen Grundbesitzer galten dabei nicht als weniger streng, sondern sogar als besonders fordernd gegenüber ihren Untertanen. Gleichzeitig war es auch in Innsbruck der Klerus, der sich in großen Teilen um das Sozialwesen, Krankenpflege, Armen- und Waisenversorgung, Speisungen und Bildung sorgte. Der Einfluss der Kirche reichte in die materielle Welt ähnlich wie es heute der Staat mit Finanzamt, Polizei, Schulwesen und Arbeitsamt tut. Was uns heute Demokratie, Parlament und Marktwirtschaft sind, waren den Menschen vergangener Jahrhunderte Bibel und Pfarrer: Eine Realität, die die Ordnung aufrecht hält. Zu glauben, alle Kirchenmänner wären zynische Machtmenschen gewesen, die ihre ungebildeten Untertanen ausnützten, ist nicht richtig. Der Großteil sowohl des Klerus wie auch der Adeligen war fromm und gottergeben, wenn auch auf eine aus heutiger Sicht nur schwer verständliche Art und Weise. Verletzungen der Religion und Sitten wurden in der späten Neuzeit vor weltlichen Gerichten verhandelt und streng geahndet. Die Anklage bei Verfehlungen lautete Häresie, worunter eine Vielzahl an Vergehen zusammengefasst wurde. Sodomie, also jede sexuelle Handlung, die nicht der Fortpflanzung diente, Zauberei, Hexerei, Gotteslästerung – kurz jede Abwendung vom rechten Gottesglauben, konnte mit Verbrennung geahndet werden. Das Verbrennen sollte die Verurteilten gleichzeitig reinigen und sie samt ihrem sündigen Treiben endgültig vernichten, um das Böse aus der Gemeinschaft zu tilgen. Bis in die Angelegenheiten des täglichen Lebens regelte die Kirche lange Zeit das alltägliche Sozialgefüge der Menschen. Kirchenglocken bestimmten den Zeitplan der Menschen. Ihr Klang rief zur Arbeit, zum Gottesdienst oder informierte als Totengeläut über das Dahinscheiden eines Mitglieds der Gemeinde. Menschen konnten einzelne Glockenklänge und ihre Bedeutung voneinander unterscheiden. Sonn- und Feiertage strukturierten die Zeit. Fastentage regelten den Speiseplan. Familienleben, Sexualität und individuelles Verhalten hatten sich an den von der Kirche vorgegebenen Moral zu orientieren. Das Seelenheil im nächsten Leben war für viele Menschen wichtiger als das Lebensglück auf Erden, war dies doch ohnehin vom determinierten Zeitgeschehen und göttlichen Willen vorherbestimmt. Fegefeuer, letztes Gericht und Höllenqualen waren Realität und verschreckten und disziplinierten auch Erwachsene.

Während das Innsbrucker Bürgertum von den Ideen der Aufklärung nach den Napoleonischen Kriegen zumindest sanft wachgeküsst wurde, blieb der Großteil der Menschen weiterhin der Mischung aus konservativem Katholizismus und abergläubischer Volksfrömmigkeit verbunden. Religiosität war nicht unbedingt eine Frage von Herkunft und Stand, wie die gesellschaftlichen, medialen und politischen Auseinandersetzungen entlang der Bruchlinie zwischen Liberalen und Konservativ immer wieder aufzeigten. Seit der Dezemberverfassung von 1867 war die freie Religionsausübung zwar gesetzlich verankert, Staat und Religion blieben aber eng verknüpft. Die Wahrmund-Affäre, die sich im frühen 20. Jahrhundert ausgehend von der Universität Innsbruck über die gesamte K.u.K. Monarchie ausbreitete, war nur eines von vielen Beispielen für den Einfluss, den die Kirche bis in die 1970er Jahre hin ausübte. Kurz vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg nahm diese politische Krise, die die gesamte Monarchie erfassen sollte in Innsbruck ihren Anfang. Ludwig Wahrmund (1861 – 1932) war Ordinarius für Kirchenrecht an der Juridischen Fakultät der Universität Innsbruck. Wahrmund, vom Tiroler Landeshauptmann eigentlich dafür ausgewählt, um den Katholizismus an der als zu liberal eingestuften Innsbrucker Universität zu stärken, war Anhänger einer aufgeklärten Theologie. Im Gegensatz zu den konservativen Vertretern in Klerus und Politik sahen Reformkatholiken den Papst nur als spirituelles Oberhaupt, nicht aber als weltlich Instanz, an. Studenten sollten nach Wahrmunds Auffassung die Lücke und die Gegensätze zwischen Kirche und moderner Welt verringern, anstatt sie einzuzementieren. Seit 1848 hatten sich die Gräben zwischen liberal-nationalen, sozialistischen, konservativen und reformorientiert-katholischen Interessensgruppen und Parteien vertieft. Eine der heftigsten Bruchlinien verlief durch das Bildungs- und Hochschulwesen entlang der Frage, wie sich das übernatürliche Gebaren und die Ansichten der Kirche, die noch immer maßgeblich die Universitäten besetzten, mit der modernen Wissenschaft vereinbaren ließen. Liberale und katholische Studenten verachteten sich gegenseitig und krachten immer aneinander. Bis 1906 war Wahrmund Teil der Leo-Gesellschaft, die die Förderung der Wissenschaft auf katholischer Basis zum Ziel hatte, bevor er zum Obmann der Innsbrucker Ortsgruppe des Vereins Freie Schule wurde, der für eine komplette Entklerikalisierung des gesamten Bildungswesens eintrat. Vom Reformkatholiken wurde er zu einem Verfechter der kompletten Trennung von Kirche und Staat. Seine Vorlesungen erregten immer wieder die Aufmerksamkeit der Obrigkeit. Angeheizt von den Medien fand der Kulturkampf zwischen liberalen Deutschnationalisten, Konservativen, Christlichsozialen und Sozialdemokraten in der Person Ludwig Wahrmunds eine ideale Projektionsfläche. Was folgte waren Ausschreitungen, Streiks, Schlägereien zwischen Studentenverbindungen verschiedener Couleur und Ausrichtung und gegenseitige Diffamierungen unter Politikern. Die Los-von-Rom Bewegung des Deutschradikalen Georg Ritter von Schönerer (1842 – 1921) krachte auf der Bühne der Universität Innsbruck auf den politischen Katholizismus der Christlichsozialen. Die deutschnationalen Akademiker erhielten Unterstützung von den ebenfalls antiklerikalen Sozialdemokraten sowie von Bürgermeister Greil, auf konservativer Seite sprang die Tiroler Landesregierung ein. Die Wahrmund Affäre schaffte es als Kulturkampfdebatte bis in den Reichsrat. Für Christlichsoziale war es ein „Kampf des freissinnigen Judentums gegen das Christentum“ in dem sich „Zionisten, deutsche Kulturkämpfer, tschechische und ruthenische Radikale“ in einer „internationalen Koalition“ als „freisinniger Ring des jüdischen Radikalismus und des radikalen Slawentums“ präsentierten. Wahrmund hingegen bezeichnete in der allgemein aufgeheizten Stimmung katholische Studenten als „Verräter und Parasiten“. Als Wahrmund 1908 eine seiner Reden, in der er Gott, die christliche Moral und die katholische Heiligenverehrung anzweifelte, in Druck bringen ließ, erhielt er eine Anzeige wegen Gotteslästerung. Nach weiteren teils gewalttätigen Versammlungen sowohl auf konservativer und antiklerikaler Seite, studentischen Ausschreitungen und Streiks musste kurzzeitig sogar der Unibetrieb eingestellt werden. Wahrmund wurde zuerst beurlaubt, später an die deutsche Universität Prag versetzt.

Auch in der Ersten Republik war die Verbindung zwischen Kirche und Staat stark. Der christlichsoziale, als Eiserner Prälat in die Geschichte eingegangen Ignaz Seipel schaffte es in den 1920er Jahren bis ins höchste Amt des Staates. Bundeskanzler Engelbert Dollfuß sah seinen Ständestaat als Konstrukt auf katholischer Basis als Bollwerk gegen den Sozialismus. Auch nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg waren Kirche und Politik in Person von Bischof Rusch und Kanzler Wallnöfer ein Gespann. Erst dann begann eine ernsthafte Trennung. Glaube und Kirche haben noch immer ihren fixen Platz im Alltag der Innsbrucker, wenn auch oft unbemerkt. Die Kirchenaustritte der letzten Jahrzehnte haben der offiziellen Mitgliederzahl zwar eine Delle versetzt und Freizeitevents werden besser besucht als Sonntagsmessen. Die römisch-katholische Kirche besitzt aber noch immer viel Grund in und rund um Innsbruck, auch außerhalb der Mauern der jeweiligen Klöster und Ausbildungsstätten. Etliche Schulen in und rund um Innsbruck stehen ebenfalls unter dem Einfluss konservativer Kräfte und der Kirche. Und wer immer einen freien Feiertag genießt, ein Osterei ans andere peckt oder eine Kerze am Christbaum anzündet, muss nicht Christ sein, um als Tradition getarnt im Namen Jesu zu handeln.

Maria help Innsbruck!

The veneration of saints and popular piety always walked a fine line between faith, superstition and magic. In the Alps, where people were more exposed to the almost inexplicable environment than in other regions, this form of faith took on remarkable and often bizarre forms. Saints were invoked for help with various everyday tasks. St Anne was supposed to protect the house and hearth, while St Notburga of Rattenberg, who was particularly popular in Tyrol, was prayed to for a good harvest. When fertilisers and agricultural machinery were increasingly used for this purpose, she rose to become the patron saint of women wearing traditional costumes. Miners entrusted their fate in their dangerous job underground to St Barbara and St Bernard. The chapel at the manor houses in Halltal near Innsbruck provides a fascinating insight into the world of faith between Begging spirit and worship of various local patron saints. The saint who still outshines all others in terms of veneration is Mary. From the consecration of herbs at the Assumption of Mary to the right-turning water in Maria Waldrast at the foot of the Serles and votive images in churches and chapels, she is a favourite permanent guest in popular piety. If you take a careful stroll through Innsbruck, you will find a special image on the facades of buildings time and again: the Gnadenbild Mariahilf by Lucas Cranach (ca. 1472 - 1553).

Cranach's Madonna is one of the most popular and most frequently copied depictions of Mary in the Alpine region. The painting is a reinterpretation of the classic iconographic Mother of God. Similar to the Mona Lisa da Vinci, which was painted at a similar time, Mary smiles mischievously at the viewer. Cranach dispensed with any form of sacralisation such as a crescent moon or halo and has her appear in contemporary everyday clothing. The red-blonde hair of mother and child transports her from Palestine to Europe. The saint and virgin Mary became an ordinary woman with a child from the upper middle class of the 16th century.

The creation, journey and veneration of the Mariahilf miraculous image tell the story of the Reformation, Counter-Reformation and popular piety in the German lands in miniature. The odyssey of the painting, which measures just 78 x 47 cm, began in what is now Thuringia at the royal court, one of the cultural centres of Europe at the time. Elector Frederick III of Saxony (1463 - 1525) was a pious man. He owned one of the most extensive collections of relics of the time. Despite his deep roots in the popular belief in relics and his pronounced penchant for Marian devotion, he supported Martin Luther in 1518 not only for religious reasons, but also for reasons of power politics. Free passage from the powerful prince and accommodation at Wartburg Castle enabled Luther to work on the German translation of the Holy Scriptures and his vision of a new, reformed church.

As was customary at the time, Friedrich also had a Art Director in his entourage. Lucas Cranach had been a court painter in Wittenberg since 1515. Like other painters of his time, Cranach was not only extremely productive, but also extremely enterprising. In addition to his artistic activities, he ran a pharmacy and a wine tavern in Wittenberg. Thanks to his financial prosperity and reputation, he was mayor of the town from 1528. Cranach was regarded as a quick painter with great output. He recognised art as a medium for capturing and disseminating the spirit of the times. Like Albrecht Dürer, he created popular works with a wide reach. His portraits of the high society of the time still characterise our image of celebrities today, such as those of his employer Frederick, Maximilian I, Martin Luther and his colleague Dürer.

Cranach and the church critics Philipp Melanchthon and Martin Luther met at Wittenberg Castle. It was through this acquaintance at the latest that the artist became a supporter of the new, reformed Christianity, which did not yet have an official manifestation. The ambiguities in the religious beliefs and practices of this period before the official schism are reflected in Cranach's works. Despite Luther and Melanchthon's rejection of the veneration of saints, the cult of the Virgin Mary and iconographic representations in churches, Cranach continued to paint for his patrons according to their taste.

Just as unclear as the transition from one denomination to another in the 16th century is the date of origin of the The miraculous image of Mariahilf. Cranach painted it sometime between 1510 and 1537 either for the household of Frederick's sister-in-law, Duchess Barbara of Saxony, or for the Church of the Holy Cross in Dresden. Art experts are still divided today. The friendship between Cranach and Martin Luther suggests that Cranach painted it after his conversion to Lutheranism and that this secularised depiction of a mother and child is an expression of a new religious world view. However, it is entirely possible that the business-minded artist painted the picture without any ideological background, but as an expression of the fashion of the time even before Luther's arrival in Wittenberg.

After Frederick's death, Cranach entered the service of his successor, John Frederick I of Saxony. When his employer was taken prisoner by the emperor after the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547, court painter Cranach followed him to Augsburg and Innsbruck despite his advanced age. After five years in the wake of the hostage, who was probably housed in luxury, Cranach returned to Wittenberg, where he succumbed to his biblical age by the standards of the time.

The Gnadenbild Mariahilf was transferred to the Kunstkammer of the Saxon sovereign during the turbulent years of the confessional wars, probably to save it from destruction by zealous iconoclasts. Almost 65 years later, like its creator before it, it was to find its way to Innsbruck along winding paths. When the art-loving Bishop of Passau from the House of Habsburg was a guest at court in Dresden in 1611, he chose Cranach's miraculous painting as a gift and took it with him to his prince-bishop's residence on the Danube. His cathedral dean saw it there and was so impressed that he had a copy made for his home altar. A pilgrimage cult quickly developed around the picture.

When the Bishop of Passau became Archduke Leopold V of Austria and Prince of Tyrol seven years later, the popular painting moved with its owner to the court in Innsbruck. His Tuscan wife Claudia de Medici kept the cult of the Virgin Mary in the Italian tradition alive even after his death. Both the Servite Church and the Capuchin monastery were given altars and images of the Virgin Mary. However, nothing was more popular than Cranach's miraculous image. In order to protect the city during the Thirty Years' War, the image was often taken from the court chapel and displayed for public veneration. During these mass prayers, the desperate population of Innsbruck shouted a loud "Maria Hilf" ("Mary Help") at the small painting, a practice that had become part of popular belief thanks to the Jesuits. In 1647, at the moment of greatest need, the Tyrolean estates swore to build a church around the painting to protect the country from devastation by Bavarian and Swedish troops. The fact that the reformed depiction of St Mary, painted by a friend of Martin Luther, was invoked to protect the city from Protestant troops is probably not without a certain irony.

Although the Mariahilf church was built, the painting was exhibited in 1650 in the parish church of St Jakob within the safe city walls. The newly built church received a copy made by Michael Waldmann. It was not to be the last of its kind. The motif and Cranach's depiction of the Mother of God became extremely popular and can still be found today not only in churches but also on countless private houses. Art became a mass phenomenon through these copies. The image of the Virgin Mary had migrated from the private property of the Saxon prince to the public sphere. Centuries before Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, Cranach and Dürer had become widely copied artists and their paintings had become part of public space and everyday life. The original of the The miraculous image of Mariahilf may hang in St Jacob's Cathedral, but the copy and the parish that grew up around it gave its name to an entire district.