Servitenkirche

Maria-Theresienstrasse 42

Worth knowing

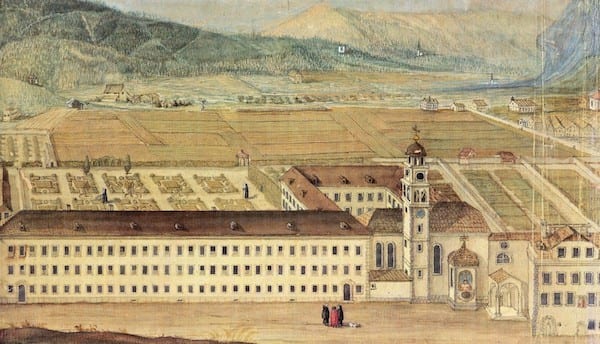

The history of the Servite Church is more fascinating than its modest appearance suggests. Anna Catarina Gonzaga (1566–1621), the second wife of Archduke Ferdinand II, founded the first establishment of the “Ordo Servorum Mariae” (Order of the Servants of Mary) in Innsbruck in 1612 with the Servite Monastery. At that time, the monastery was the only convent north of the Alps dedicated to Saint Joseph. The mosaic in the colorful entrance vault displays the coat of arms of the Duchy of Mantua with its four black eagles and red lion, alongside the coat of arms of the Archduchy of Austria. It symbolizes the union of Ferdinand and Anna Catarina Gonzaga and their dynasties. Although the Italian city-states had already passed their prime, they still possessed the means to marry into the highest circles of European aristocracy. During this era of church division, the northern Italian principalities and the Habsburgs formed the Catholic stronghold of Europe. Establishing this strict order was a major concern for the devout rulers from northern Italy. As a mendicant order, the Servites initially devoted themselves to caring for the poor. During the Reformation, the Servite Order, which originated in Tuscany, was completely dissolved in German-speaking regions and only began to spread again from Innsbruck in the 17th century.

The Servite Order faced many challenges in Innsbruck. Just a few years after the church was consecrated, the first building largely burned down in 1620. The Gothic entrance area of the original church with its distinctive columns survived. The founder’s plan to be buried in the church she had endowed had to be postponed. Johann Martin and Georg Anton Gumpp designed the new building in Baroque style in 1626. By then, Anna Caterina Gonzaga had already passed away. Instead of being buried in the Servite Church as planned, she was first interred in the Servite nuns’ convent and later in the Jesuit Church. It was not until 1693 that she was reburied in the Servite Church alongside her daughter. In the 20th century, the Servite Monastery once again faced dissolution. On November 3, 1938, the National Socialists dissolved the Servite Order as the first monastery in Innsbruck “for the protection of the people.” In Catholic Tyrol, actions against the Church had to be carefully planned and communicated. Often, the most outrageous stories were fabricated for this purpose. The Austrian edition of the “Völkischer Beobachter” on November 4, 1938 stated the reason as follows:

“State police investigations in the Servite Monastery in Innsbruck revealed such immoral conditions that it is impossible to present them publicly. The monastery in question is a den of vice of the highest order, behind which the anti-state behavior, evidenced by discovered writings, fades into the background.”

On December 15, 1943, the Servite Church was destroyed during the first air raid on Innsbruck. Only small parts of the historic structure and some paintings and relics in the art chamber and monastery museum remained intact. The striking painting on the exterior was recreated after 1945 during reconstruction by Hans Andre (1902–1991), who also restored the damaged Hospital Church after the war. Born in Innsbruck, Andre attended the trade school—today’s HTL—like many Tyrolean artists of the 20th century. After five years at the University of Applied Arts and a brief collaboration with Clemens Holzmeister, he returned to Innsbruck. After World War II, he focused on restoring churches damaged by the war. His interpretation of the Crucifixion scene on the exterior façade, simultaneously baroque and modern, reflects the subdued mood of the post-war era. Andre also created the paintings inside the church.

Anna Caterina Gonzaga - die fromme Landesfürstin

Innsbruckers like to see themselves as a kind of northern outpost of Italy, a mixture of Italian art de vivre and German precision. In addition to the preference for wine and beer in equal measure, the Tyrolean sovereigns' fondness for the daughters of the Italian high aristocracy and their influence on the city could also be a reason for this. Anna Caterina Gonzaga (1566 - 1621), known as "Principessa"Born in the city of Mantua at the age of 16, he was forced to marry Ferdinand II, the prince of Tyrol, who was known as a bon vivant. While his first wife Philippine Welser was still alive but already ill, he had asked for her hand in marriage. At the time, Mantua was one of the richest royal courts in Europe and a centre of the Renaissance. Ferdinand was already 53 at the time of the wedding and was also Anna Caterina Gonzaga's uncle thanks to unfavourable entanglements in the wedding politics of previous decades. In order for the wedding to take place, the Pope had to issue a special licence. The marriage was necessary because Ferdinand was unable to claim an heir to the throne from his first marriage. Ferdinand II also had "only" three daughters with Anna Catarina. For the House of Habsburg, the marriage meant a considerable dowry, which came to Tyrol from Mantua. In return, Anna Caterina Gonzaga's father was able to boast the title Hoheit which Emperor Rudolf II, like Ferdinand a Habsburg, bestowed on him.

The pious Mantovan woman took refuge in her faith in Tyrol. After the Jesuits under Ferdinand I and the Franciscans, the Capuchins settled in Innsbruck in 1593 under the care of Anna Caterina Gonzaga. In the Silbergasse at the eastern end of the Hofgarten, a Regelhaus, um es der Landesfürstin zu ermöglichen ihrem Glauben in aller Stille nachgehen zu können, ohne sich in aller Strenge dem Klosterleben unterwerfen zu müssen. Nach dem Tod Ferdinands im Jahre 1595 gründete die nunmehrige Landesfürstin von Tirol und tiefgläubige Frau das Servitenkloster in Innsbruck. Die Serviten waren im Volk sehr beliebt, hielten sie doch Armenspeisungen ab. Großzügige Stiftungen an die Kirche waren nicht ungewöhnlich. Neben einem gottgefälligen Leben waren Geschenke an die Kirche und Gebete nach dem Ableben eine Möglichkeit, das Seelenheil zu erlangen. Mitglieder des Hauses Habsburg im Speziellen hatten diese Sitte in ihrer Frömmigkeit seit jeher betrieben und ließen auch in der Neuzeit nicht davon ab. Anna Caterina Gonzaga selbst trat mit ihrer Tochter Maria in das Regelhaus ein, ein offenes Damenkloster mit etwas legereren Regeln, wo sie bis an ihr Lebensende ihrem Glauben nachging. Ihre Grablege fand sie zunächst in der Gruft des Servitinnenklosters gemeinsam mit ihrer Tochter. 1693 wurden die sterblichen Überreste der beiden Frauen in die Jesuitenkirche überstellt. Erst im Jahr 1906 fanden sie ihre letzte Ruhestätte im Servitenkloster in der Maria-Theresien-Straße.

Risen from the ruins

Nach Kriegsende kontrollierten US-Truppen für zwei Monate Tirol. Anschließend übernahm die Siegermacht Frankreich die Verwaltung. Den Tirolern blieb die sowjetische Besatzung, die über Ostösterreich hereinbrach, erspart. Besonders in den ersten drei Nachkriegsjahren war der Hunger der größte Feind der Menschen. Der Mai 1945 brachte nicht nur das Kriegsende, sondern auch Schnee. Der Winter 1946/47 ging als besonders kalt und lang in die Tiroler Klimageschichte ein, der Sommer als besonders heiß und trocken. Es kam zu Ernteausfällen von bis zu 50%. Die Versorgungslage war vor allem in der Stadt in der unmittelbaren Nachkriegszeit katastrophal. Die tägliche Nahrungsmittelbeschaffung wurde zur lebensgefährlichen Sorge im Alltag der Innsbrucker. Neben den eigenen Bürgern mussten auch tausende von Displaced PersonsThe Tyrolean government had to feed a large number of people, freed forced labourers and occupying soldiers. To accomplish this task, the Tyrolean provincial government had to rely on outside help. The chairman of the UNRRA (Note: United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration), which supplied war zones with essentials, Fiorello La Guardia counted Austria "to those peoples of the world who are closest to starvation." Milk, bread, eggs, sugar, flour, fat - there was too little of everything. The French occupation was unable to meet the demand for the required kilocalories per capita, as the local population and the emergency services often lacked supplies. Until 1946, they even took goods from the Tyrolean economy.

Die Lebensmittelversorgung erfolgte schon wenige Wochen nach Kriegsende über Lebensmittelkarten. Erwachsene mussten eine Bestätigung des Arbeitsamtes vorlegen, um an diese Karten zu kommen. Die Rationen unterschieden sich je nach Kategorie der Arbeiter. Schwerstarbeiter, Schwangere und stillende Mütter erhielten Lebensmittel im „Wert“ von 2700 Kalorien. Handwerker mit leichten Berufen, Beamte und Freiberufler erhielten 1850 Kilokalorien, Angestellte 1450 Kalorien. Hausfrauen und andere „Normalverbraucher“ konnten nur 1200 Kalorien beziehen. Zusätzlich gab es Initiativen wie Volksküchen oder Ausspeisungen für Schulkinder, die von ausländischen Hilfsorganisationen übernommen wurden. Aus Amerika kamen Carepakete von der Wohlfahrtsorganisation Cooperative for American Remittances to Europe. Many children were sent to foster homes in Switzerland in the summer to regain their strength and put a few extra kilos on their ribs.

However, all these measures were not enough for everyone. Housewives and other "normal consumers" in particular suffered from the low allocations. Despite the risk of being arrested, many Innsbruck residents travelled to the surrounding villages to hoard. Those who had money paid sometimes utopian prices to the farmers. Those who had none had to beg for food. In extreme cases, women whose husbands had been killed, captured or were missing saw no other way out than to prostitute themselves. These women, especially the unfortunate ones who became pregnant, had to endure the worst abuse for themselves and their offspring. Austria was still 30 years away from legalised abortion.

Politicians were largely powerless in the face of this. Even in normal times, it was impossible to pacify all interests. Many decisions between the parliament in Vienna, the Tyrolean provincial parliament and Innsbruck town hall were incomprehensible to the people. While children had to do without fruit and vitamins, some farmers legally distilled profitable schnapps. Official buildings and commercial enterprises were given free rein by the Innsbruck electricity company, while private households were restricted access to electricity at several times of the day from October 1945. The same disadvantage for households compared to businesses applied to the supply of coal. The old rifts between town and country grew wider and more hateful. Innsbruckers accused the surrounding population of deliberately withholding food for the black market. There were robberies, thefts and woodcutting. Transports at the railway station were guarded by armed units. Obtaining food from a camp was both illegal and commonplace. Children and young people roamed the city hungry and took every opportunity to get something to eat or fuel. The first Tyrolean governor Gruber, himself an illegal member of the resistance during the war, understood the situation of the people who rebelled against the system, but was unable to do anything about it. The mayor of Innsbruck, Anton Melzer, also had his hands tied. Not only was it difficult to reconcile the needs of all interest groups, there were repeated cases of corruption and favours to relatives and acquaintances among the civil servants. Gruber's successor in the provincial governor's chair, Alfons Weißgatterer, had to survive several small riots when popular anger was vented and stones were thrown in the direction of the Landhaus. Tiroler Tageszeitung. The paper was founded in 1945 under the administration of the US armed forces for the purposes of democratisation and denazification, but was transferred the following year to Schlüssel GmbH under the management of ÖVP politician Joseph Moser. Thanks to the high circulation and its almost direct influence on the content, the Tyrolean provincial government was able to steer the public mood:

„Are the broken windows that clattered from the country house into the street yesterday suitable arguments to prove our will to rebuild? Shouldn't we remember that economic difficulties have never been resolved by demonstrations and rallies in any country?“

The housing situation was at least as bad. An estimated 30,000 Innsbruck residents were homeless, living in cramped conditions with relatives or in shanty towns such as the former labour camp in Reichenau, the shanty town for displaced persons from the former German territories of Europe, popularly known as the "Ausländerlager", or the "Ausländerlager". Bocksiedlung. Weniges erinnert noch an den desaströsen Zustand, in dem sich Innsbruck nach den Luftangriffen der letzten Kriegsjahre in den ersten Nachkriegsjahren befand. Zehntausende Bürger halfen mit, Schutt und Trümmer von den Straßen zu schaffen. Die Maria-Theresien-Straße, die Museumstraße, das Bahnhofsviertel, Wilten oder die Pradlerstraße wären wohl um einiges ansehnlicher, hätte man nicht die Löcher im Straßenbild schnell stopfen müssen, um so schnell als möglich Wohnraum für die vielen Obdachlosen und Rückkehrer zu schaffen. Ästhetik aber war ein Luxus, den man sich in dieser Situation nicht leisten konnte. Die ausgezehrte Bevölkerung benötigte neuen Wohnraum, um den gesundheitsschädlichen Lebensbedingungen, in denen Großfamilien teils in Einraumwohnungen einquartiert waren, zu entfliehen.

"The emergency situation jeopardises the comfort of the home. It eats away at the roots of joie de vivre. No one suffers more than the woman whose happiness is to see a contented, cosy family circle around her. What a strain on mental strength is required by the daily gruelling struggle for a little shopping, the hardship of queuing, the disappointment of rejections and refusals and the look of discouragement on the faces of loved ones tormented by deprivation."

What is in the Tiroler Tageszeitung was only part of the harsh reality of everyday life. As after the First World War, when the Spanish flu claimed many victims, there was also an increase in dangerous infections in 1945. Vaccines against tuberculosis could not be delivered in the first winter. Hospital beds were also in short supply. Even though the situation eased after 1947, living conditions in Tyrol remained precarious. It took years before there were any noticeable improvements. Food rationing was discontinued on 1 July 1953. In the same year, Mayor Greiter was able to announce that all the buildings destroyed during the air raids had been repaired.

This was also thanks to the occupying forces. The French troops under Emile Bethouart behaved very mildly and co-operatively towards the former enemy and were friendly and open-minded towards the Tyrolean culture and population. Initially hostile towards the occupying power - yet another war had been lost - the scepticism of the people of Innsbruck gradually gave way. The soldiers were particularly popular with the children because of the chocolates and sweets they handed out. Many people were given jobs within the French administration. Thanks to the uniformed soldiers, many a Tyrolean saw of the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division, die bis September 1945 den Großteil der Soldaten stellten, zum ersten Mal dunkelhäutige Menschen. Die Besatzer stellten, soweit dies in ihren Möglichkeiten lag, auch die Versorgung sicher. Zeitzeugen erinnern sich mit Grauen an die Konservendosen, die sie als Hauptnahrungsmittel erhielten. Um die Logistik zu erleichtern legten die Franzosen bereits 1946 den Grundstein für den neuen Flughafen auf der Ulfiswiese in der Höttinger Au, der den 20 Jahre zuvor eröffneten in der Reichenau nach zwei Jahren Bauzeit ersetzte. Das Franzosendenkmal am Landhausplatz erinnert an die französische Besatzungszeit. Am Emile Bethouart footbridgeThe memorial plaque on the river Inn, which connects St. Nikolaus and the city centre, is a good expression of the relationship between the occupation and the population:

"Arrived as a winner.

Remained as a protector.

Returned home as a friend."

In addition to material hardship, society was characterised by the collective trauma of war. The adults of the 1950s were products of the education of the interwar period and National Socialism. Men who had fought at the front could only talk about their horrific experiences in certain circles as war losers; women usually had no forum at all to process their fears and worries. Domestic violence and alcoholism were widespread. Teachers, police officers, politicians and civil servants often came from National Socialist supporters, who did not simply disappear with the end of the war, but were merely hushed up in public. On Innsbruck People's Court Although there were a large number of trials against National Socialists under the direction of the victorious powers, the number of convictions did not reflect the extent of what had happened. The majority of those accused went free. Particularly incriminated representatives of the system were sent to prison for some time, but were able to resume their old lives relatively undisturbed after serving their sentences, at least professionally. It was not just a question of drawing a line under the past decades; yesterday's perpetrators were needed to keep today's society running.

The problem with this strategy of suppression was that no one took responsibility for what had happened, even if there was great enthusiasm and support for National Socialism, especially at the beginning. There was hardly a family that did not have at least one member with a less than glorious history between 1933 and 1945. Shame about what had happened since 1938 and in Austria's politics over the years was mixed with the fear of being treated as a war culprit by the occupying powers of the USA, Great Britain, France and the USSR in a similar way to 1918. A climate arose in which no one, neither those involved nor the following generation, spoke about what had happened. For a long time, this attitude prevented people from coming to terms with what had happened since 1933. The myth of Austria as the first victim of National Socialism, which only began to slowly crumble with the Waldheim affair in the 1980s, was born. Police officers, teachers, judges - they were all left in their jobs despite their political views. Society needed them to keep going.

An example of the generously spread cloak of oblivion with a strong connection to Innsbruck is the life of the doctor Burghard Breitner (1884-1956). Breitner grew up in a well-to-do middle-class household. The Villa Breitner at Mattsee was home to a museum about the German nationalist poet Josef Viktor Scheffel, who was honoured by his father. After graduating from high school, Breitner decided against a career in literature in favour of studying medicine. He then decided to do his military service and began his career as a doctor. In 1912/13 he served as a military doctor in the Balkan War. In 1914, he was sent to the Eastern Front, where he was taken prisoner of war by the Russians. As a doctor, he sacrificially cared for his comrades in the prison camp. It was not until 1920 that he was recognised as a hero and "Angel of Siberia" returned to Austria from the prison camp. In 1932, he began his career at the University of Innsbruck. In 1938, Breitner was faced with the problem that, due to his paternal grandmother's Jewish background, he had to take the "Great Aryan proof" could not provide. However, thanks to his good relationship with the Rector of Innsbruck University and important National Socialists, he was ultimately able to continue working at the university hospital. During the Nazi regime, Breitner was responsible for forced sterilisations and "Voluntary emasculation", even though he probably did not personally carry out any of the operations. After the war, the "Angel of Siberia" managed to wriggle through the denazification process with some difficulty. In 1951, he was nominated as a candidate for the VDUa political rallying point for staunch National Socialists, as a candidate for the federal presidential election. Breitner became Rector of the University of Innsbruck in 1952. After his death, the city of Innsbruck dedicated a grave of honour to him at Innsbruck West Cemetery. In Reichenau, a street is dedicated to him in the immediate vicinity of the site of the former concentration camp.

Believe, Church and Power

Die Fülle an Kirchen, Kapellen, Kruzifixen und Wandmalereien im öffentlichen Raum wirkt auf viele Besucher Innsbrucks aus anderen Ländern eigenartig. Nicht nur Gotteshäuser, auch viele Privathäuser sind mit Darstellungen der Heiligen Familie oder biblischen Szenen geschmückt. Der christliche Glaube und seine Institutionen waren in ganz Europa über Jahrhunderte alltagsbestimmend. Innsbruck als Residenzstadt der streng katholischen Habsburger und Hauptstadt des selbsternannten Heiligen Landes Tirol wurde bei der Ausstattung mit kirchlichen Bauwerkern besonders beglückt. Allein die Dimension der Kirchen umgelegt auf die Verhältnisse vergangener Zeiten sind gigantisch. Die Stadt mit ihren knapp 5000 Einwohnern besaß im 16. Jahrhundert mehrere Kirchen, die in Pracht und Größe jedes andere Gebäude überstrahlte, auch die Paläste der Aristokratie. Das Kloster Wilten war ein Riesenkomplex inmitten eines kleinen Bauerndorfes, das sich darum gruppierte. Die räumlichen Ausmaße der Gotteshäuser spiegelt die Bedeutung im politischen und sozialen Gefüge wider.

Die Kirche war für viele Innsbrucker nicht nur moralische Instanz, sondern auch weltlicher Grundherr. Der Bischof von Brixen war formal hierarchisch dem Landesfürsten gleichgestellt. Die Bauern arbeiteten auf den Landgütern des Bischofs wie sie auf den Landgütern eines weltlichen Fürsten für diesen arbeiteten. Damit hatte sie die Steuer- und Rechtshoheit über viele Menschen. Die kirchlichen Grundbesitzer galten dabei nicht als weniger streng, sondern sogar als besonders fordernd gegenüber ihren Untertanen. Gleichzeitig war es auch in Innsbruck der Klerus, der sich in großen Teilen um das Sozialwesen, Krankenpflege, Armen- und Waisenversorgung, Speisungen und Bildung sorgte. Der Einfluss der Kirche reichte in die materielle Welt ähnlich wie es heute der Staat mit Finanzamt, Polizei, Schulwesen und Arbeitsamt tut. Was uns heute Demokratie, Parlament und Marktwirtschaft sind, waren den Menschen vergangener Jahrhunderte Bibel und Pfarrer: Eine Realität, die die Ordnung aufrecht hält. Zu glauben, alle Kirchenmänner wären zynische Machtmenschen gewesen, die ihre ungebildeten Untertanen ausnützten, ist nicht richtig. Der Großteil sowohl des Klerus wie auch der Adeligen war fromm und gottergeben, wenn auch auf eine aus heutiger Sicht nur schwer verständliche Art und Weise. Verletzungen der Religion und Sitten wurden in der späten Neuzeit vor weltlichen Gerichten verhandelt und streng geahndet. Die Anklage bei Verfehlungen lautete Häresie, worunter eine Vielzahl an Vergehen zusammengefasst wurde. Sodomie, also jede sexuelle Handlung, die nicht der Fortpflanzung diente, Zauberei, Hexerei, Gotteslästerung – kurz jede Abwendung vom rechten Gottesglauben, konnte mit Verbrennung geahndet werden. Das Verbrennen sollte die Verurteilten gleichzeitig reinigen und sie samt ihrem sündigen Treiben endgültig vernichten, um das Böse aus der Gemeinschaft zu tilgen. Bis in die Angelegenheiten des täglichen Lebens regelte die Kirche lange Zeit das alltägliche Sozialgefüge der Menschen. Kirchenglocken bestimmten den Zeitplan der Menschen. Ihr Klang rief zur Arbeit, zum Gottesdienst oder informierte als Totengeläut über das Dahinscheiden eines Mitglieds der Gemeinde. Menschen konnten einzelne Glockenklänge und ihre Bedeutung voneinander unterscheiden. Sonn- und Feiertage strukturierten die Zeit. Fastentage regelten den Speiseplan. Familienleben, Sexualität und individuelles Verhalten hatten sich an den von der Kirche vorgegebenen Moral zu orientieren. Das Seelenheil im nächsten Leben war für viele Menschen wichtiger als das Lebensglück auf Erden, war dies doch ohnehin vom determinierten Zeitgeschehen und göttlichen Willen vorherbestimmt. Fegefeuer, letztes Gericht und Höllenqualen waren Realität und verschreckten und disziplinierten auch Erwachsene.

Während das Innsbrucker Bürgertum von den Ideen der Aufklärung nach den Napoleonischen Kriegen zumindest sanft wachgeküsst wurde, blieb der Großteil der Menschen weiterhin der Mischung aus konservativem Katholizismus und abergläubischer Volksfrömmigkeit verbunden. Religiosität war nicht unbedingt eine Frage von Herkunft und Stand, wie die gesellschaftlichen, medialen und politischen Auseinandersetzungen entlang der Bruchlinie zwischen Liberalen und Konservativ immer wieder aufzeigten. Seit der Dezemberverfassung von 1867 war die freie Religionsausübung zwar gesetzlich verankert, Staat und Religion blieben aber eng verknüpft. Die Wahrmund-Affäre, die sich im frühen 20. Jahrhundert ausgehend von der Universität Innsbruck über die gesamte K.u.K. Monarchie ausbreitete, war nur eines von vielen Beispielen für den Einfluss, den die Kirche bis in die 1970er Jahre hin ausübte. Kurz vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg nahm diese politische Krise, die die gesamte Monarchie erfassen sollte in Innsbruck ihren Anfang. Ludwig Wahrmund (1861 – 1932) war Ordinarius für Kirchenrecht an der Juridischen Fakultät der Universität Innsbruck. Wahrmund, vom Tiroler Landeshauptmann eigentlich dafür ausgewählt, um den Katholizismus an der als zu liberal eingestuften Innsbrucker Universität zu stärken, war Anhänger einer aufgeklärten Theologie. Im Gegensatz zu den konservativen Vertretern in Klerus und Politik sahen Reformkatholiken den Papst nur als spirituelles Oberhaupt, nicht aber als weltlich Instanz, an. Studenten sollten nach Wahrmunds Auffassung die Lücke und die Gegensätze zwischen Kirche und moderner Welt verringern, anstatt sie einzuzementieren. Seit 1848 hatten sich die Gräben zwischen liberal-nationalen, sozialistischen, konservativen und reformorientiert-katholischen Interessensgruppen und Parteien vertieft. Eine der heftigsten Bruchlinien verlief durch das Bildungs- und Hochschulwesen entlang der Frage, wie sich das übernatürliche Gebaren und die Ansichten der Kirche, die noch immer maßgeblich die Universitäten besetzten, mit der modernen Wissenschaft vereinbaren ließen. Liberale und katholische Studenten verachteten sich gegenseitig und krachten immer aneinander. Bis 1906 war Wahrmund Teil der Leo-Gesellschaft, die die Förderung der Wissenschaft auf katholischer Basis zum Ziel hatte, bevor er zum Obmann der Innsbrucker Ortsgruppe des Vereins Freie Schule wurde, der für eine komplette Entklerikalisierung des gesamten Bildungswesens eintrat. Vom Reformkatholiken wurde er zu einem Verfechter der kompletten Trennung von Kirche und Staat. Seine Vorlesungen erregten immer wieder die Aufmerksamkeit der Obrigkeit. Angeheizt von den Medien fand der Kulturkampf zwischen liberalen Deutschnationalisten, Konservativen, Christlichsozialen und Sozialdemokraten in der Person Ludwig Wahrmunds eine ideale Projektionsfläche. Was folgte waren Ausschreitungen, Streiks, Schlägereien zwischen Studentenverbindungen verschiedener Couleur und Ausrichtung und gegenseitige Diffamierungen unter Politikern. Die Los-von-Rom Bewegung des Deutschradikalen Georg Ritter von Schönerer (1842 – 1921) krachte auf der Bühne der Universität Innsbruck auf den politischen Katholizismus der Christlichsozialen. Die deutschnationalen Akademiker erhielten Unterstützung von den ebenfalls antiklerikalen Sozialdemokraten sowie von Bürgermeister Greil, auf konservativer Seite sprang die Tiroler Landesregierung ein. Die Wahrmund Affäre schaffte es als Kulturkampfdebatte bis in den Reichsrat. Für Christlichsoziale war es ein „Kampf des freissinnigen Judentums gegen das Christentum“ in dem sich „Zionisten, deutsche Kulturkämpfer, tschechische und ruthenische Radikale“ in einer „internationalen Koalition“ als „freisinniger Ring des jüdischen Radikalismus und des radikalen Slawentums“ präsentierten. Wahrmund hingegen bezeichnete in der allgemein aufgeheizten Stimmung katholische Studenten als „Verräter und Parasiten“. Als Wahrmund 1908 eine seiner Reden, in der er Gott, die christliche Moral und die katholische Heiligenverehrung anzweifelte, in Druck bringen ließ, erhielt er eine Anzeige wegen Gotteslästerung. Nach weiteren teils gewalttätigen Versammlungen sowohl auf konservativer und antiklerikaler Seite, studentischen Ausschreitungen und Streiks musste kurzzeitig sogar der Unibetrieb eingestellt werden. Wahrmund wurde zuerst beurlaubt, später an die deutsche Universität Prag versetzt.

Auch in der Ersten Republik war die Verbindung zwischen Kirche und Staat stark. Der christlichsoziale, als Eiserner Prälat in die Geschichte eingegangen Ignaz Seipel schaffte es in den 1920er Jahren bis ins höchste Amt des Staates. Bundeskanzler Engelbert Dollfuß sah seinen Ständestaat als Konstrukt auf katholischer Basis als Bollwerk gegen den Sozialismus. Auch nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg waren Kirche und Politik in Person von Bischof Rusch und Kanzler Wallnöfer ein Gespann. Erst dann begann eine ernsthafte Trennung. Glaube und Kirche haben noch immer ihren fixen Platz im Alltag der Innsbrucker, wenn auch oft unbemerkt. Die Kirchenaustritte der letzten Jahrzehnte haben der offiziellen Mitgliederzahl zwar eine Delle versetzt und Freizeitevents werden besser besucht als Sonntagsmessen. Die römisch-katholische Kirche besitzt aber noch immer viel Grund in und rund um Innsbruck, auch außerhalb der Mauern der jeweiligen Klöster und Ausbildungsstätten. Etliche Schulen in und rund um Innsbruck stehen ebenfalls unter dem Einfluss konservativer Kräfte und der Kirche. Und wer immer einen freien Feiertag genießt, ein Osterei ans andere peckt oder eine Kerze am Christbaum anzündet, muss nicht Christ sein, um als Tradition getarnt im Namen Jesu zu handeln.

Baroque: art movement and art of living

Anyone travelling in Austria will be familiar with the domes and onion domes of churches in villages and towns. This form of church tower originated during the Counter-Reformation and is a typical feature of the Baroque architectural style. They are also predominant in Innsbruck's cityscape. Innsbruck's most famous places of worship, such as the cathedral, St John's Church and the Jesuit Church, are in the Baroque style. Places of worship were meant to be magnificent and splendid, a symbol of the victory of true faith. Religiousness was reflected in art and culture: grand drama, pathos, suffering, splendour and glory combined to create the Baroque style, which had a lasting impact on the entire Catholic-oriented sphere of influence of the Habsburgs and their allies between Spain and Hungary.

The cityscape of Innsbruck changed enormously. The Gumpps and Johann Georg Fischer as master builders as well as Franz Altmutter's paintings have had a lasting impact on Innsbruck to this day. The Old Country House in the historic city centre, the New Country House in Maria-Theresien-Straße, the countless palazzi, paintings, figures - the Baroque was the style-defining element of the House of Habsburg in the 17th and 18th centuries and became an integral part of everyday life. The bourgeoisie did not want to be inferior to the nobles and princes and had their private houses built in the Baroque style. Pictures of saints, depictions of the Mother of God and the heart of Jesus adorned farmhouses.

Baroque was not just an architectural style, it was an attitude to life that began after the end of the Thirty Years' War. The Turkish threat from the east, which culminated in the two sieges of Vienna, determined the foreign policy of the empire, while the Reformation dominated domestic politics. Baroque culture was a central element of Catholicism and its political representation in public, the counter-model to Calvin's and Luther's brittle and austere approach to life. Holidays with a Christian background were introduced to brighten up people's everyday lives. Architecture, music and painting were rich, opulent and lavish. In theatres such as the Comedihaus dramas with a religious background were performed in Innsbruck. Stations of the cross with chapels and depictions of the crucified Jesus dotted the landscape. Popular piety in the form of pilgrimages and the veneration of the Virgin Mary and saints found its way into everyday church life. Multiple crises characterised people's everyday lives. In addition to war and famine, the plague broke out particularly frequently in the 17th century. The Baroque piety was also used to educate the subjects. Even though the sale of indulgences was no longer a common practice in the Catholic Church after the 16th century, there was still a lively concept of heaven and hell. Through a virtuous life, i.e. a life in accordance with Catholic values and good behaviour as a subject towards the divine order, one could come a big step closer to paradise. The so-called Christian edification literature was popular among the population after the school reformation of the 18th century and showed how life should be lived. The suffering of the crucified Christ for humanity was seen as a symbol of the hardship of the subjects on earth within the feudal system. People used votive images to ask for help in difficult times or to thank the Mother of God for dangers and illnesses they had overcome.

The historian Ernst Hanisch described the Baroque and the influence it had on the Austrian way of life as follows:

„Österreich entstand in seiner modernen Form als Kreuzzugsimperialismus gegen die Türken und im Inneren gegen die Reformatoren. Das brachte Bürokratie und Militär, im Äußeren aber Multiethnien. Staat und Kirche probierten den intimen Lebensbereich der Bürger zu kontrollieren. Jeder musste sich durch den Beichtstuhl reformieren, die Sexualität wurde eingeschränkt, die normengerechte Sexualität wurden erzwungen. Menschen wurden systematisch zum Heucheln angeleitet.“

The rituals and submissive behaviour towards the authorities left their mark on everyday culture, which still distinguishes Catholic countries such as Austria and Italy from Protestant regions such as Germany, England or Scandinavia. The Austrians' passion for academic titles has its origins in the Baroque hierarchies. The expression Baroque prince describes a particularly patriarchal and patronising politician who knows how to charm his audience with grand gestures. While political objectivity is valued in Germany, the style of Austrian politicians is theatrical, in keeping with the Austrian bon mot of "Schaumamal".

The master builders Gumpp and the baroqueisation of Innsbruck

The works of the Gumpp family still strongly characterise the appearance of Innsbruck today. The baroque parts of the city in particular can be traced back to them. The founder of the dynasty in Tyrol, Christoph Gumpp (1600-1672), was actually a carpenter. However, his talent had chosen him for higher honours. The profession of architect or artist did not yet exist at that time; even Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci were considered craftsmen. After working on the Holy Trinity Church, the Swabian-born Gumpp followed in the footsteps of the Italian master builders who had set the tone under Ferdinand II. At the behest of Leopold V, Gumpp travelled to Italy to study theatre buildings and to learn from his contemporary style-setting colleagues his expertise for the planned royal palace. Comedihaus polish up.

His official work as court architect began in 1633. New times called for a new design, away from the Gothic-influenced architecture of the Middle Ages and the horrors of the Thirty Years' War. Over the following decades, Innsbruck underwent a complete renovation under the regency of Claudia de Medici. Gumpp passed on his title to the next two generations within the family. The Gumpps were not only active as master builders. They were also carpenters, painters, engravers and architects, which allowed them to create a wide range of works similar to the Tiroler Moderne around Franz Baumann and Clemens Holzmeister at the beginning of the 20th century to realise projects holistically. They were also involved as planners in the construction of the fortifications for national defence during the Thirty Years' War.

Christoph Gumpp's masterpiece, however, was the construction of the Comedihaus in the former ballroom. The oversized dimensions of the then trend-setting theatre, which was one of the first of its kind in Europe, not only allowed plays to be performed, but also water games with real ships and elaborate horse ballet performances. The Comedihaus was a total work of art in and of itself, which in its significance at the time can be compared to the festival theatre in Bayreuth in the 19th century or the Elbphilharmonie today.

His descendants Johann Martin Gumpp the Elder, Georg Anton Gumpp and Johann Martin Gumpp the Younger were responsible for many of the buildings that still characterise the townscape today. The Wilten collegiate church, the Mariahilfkirche, the Johanneskirche and the Spitalskirche were all designed by the Gumpps. In addition to designing churches and their work as court architects, they also made a name for themselves as planners of secular buildings. Many of Innsbruck's town houses and city palaces, such as the Taxispalais or the Altes Landhaus in Maria-Theresien-Straße, were designed by them. With the loss of the city's status as a royal seat, the magnificent large-scale commissions declined and with them the fame of the Gumpp family. Their former home is now home to the Munding confectionery in the historic city centre. In the Pradl district, Gumppstraße commemorates the Innsbruck dynasty of master builders.

Air raids on Innsbruck

Wie der Lauf der Geschichte der Stadt unterliegt auch ihr Aussehen einem ständigen Wandel. Besonders gut sichtbare Veränderungen im Stadtbild erzeugten die Jahre rund um 1500 und zwischen 1850 bis 1900, als sich politische, wirtschaftliche und gesellschaftliche Veränderungen in besonders schnellem Tempo abspielten. Das einschneidendste Ereignis mit den größten Auswirkungen auf das Stadtbild waren aber wohl die Luftangriffe auf die Stadt im Zweiten Weltkrieg, als aus der „Heimatfront“ der Nationalsozialisten ein tatsächlicher Kriegsschauplatz wurde. Die Lage am Fuße des Brenners war über Jahrhunderte ein Segen für die Stadt gewesen, nun wurde sie zum Verhängnis. Innsbruck war ein wichtiger Versorgungsbahnhof für den Nachschub an der Italienfront. In der Nacht vom 15. auf den 16. Dezember 1943 erfolgte der erste alliierte Luftangriff auf die schlecht vorbereitete Stadt. 269 Menschen fielen den Bomben zum Opfer, 500 wurden verletzt und mehr als 1500 obdachlos. Über 300 Gebäude, vor allem in Wilten und der Innenstadt, wurden zerstört und beschädigt. Am Montag, den 18. Dezember fanden sich in den Innsbrucker Nachrichten, dem Vorgänger der Tiroler Tageszeitung, auf der Titelseite allerhand propagandistische Meldungen vom erfolgreichen und heroischen Abwehrkampf der Deutschen Wehrmacht an allen Fronten gegenüber dem Bündnis aus Anglo-Amerikanern und dem Russen, nicht aber vom Bombenangriff auf Innsbruck.

Bombenterror über Innsbruck

Innsbruck, 17. Dez. Der 16. Dezember wird in der Geschichte Innsbrucks als der Tag vermerkt bleiben, an dem der Luftterror der Anglo-Amerikaner die Gauhauptstadt mit der ganzen Schwere dieser gemeinen und brutalen Kampfweise, die man nicht mehr Kriegführung nennen kann, getroffen hat. In mehreren Wellen flogen feindliche Kampfverbände die Stadt an und richteten ihre Angriffe mit zahlreichen Spreng- und Brandbomben gegen die Wohngebiete. Schwerste Schäden an Wohngebäuden, an Krankenhäusern und anderen Gemeinschaftseinrichtungen waren das traurige, alle bisherigen Schäden übersteigende Ergebnis dieses verbrecherischen Überfalles, der über zahlreiche Familien unserer Stadt schwerste Leiden und empfindliche Belastung der Lebensführung, das bittere Los der Vernichtung liebgewordenen Besitzes, der Zerstörung von Heim und Herd und der Heimatlosigkeit gebracht hat. Grenzenloser Haß und das glühende Verlangen diese unmenschliche Untat mit schonungsloser Schärfe zu vergelten, sind die einzige Empfindung, die außer der Auseinandersetzung mit den eigenen und den Gemeinschaftssorgen alle Gemüter bewegt. Wir alle blicken voll Vertrauen auf unsere Soldaten und erwarten mit Zuversicht den Tag, an dem der Führer den Befehl geben wird, ihre geballte Kraft mit neuen Waffen gegen den Feind im Westen einzusetzen, der durch seinen Mord- und Brandterror gegen Wehrlose neuerdings bewiesen hat, daß er sich von den asiatischen Bestien im Osten durch nichts unterscheidet – es wäre denn durch größere Feigheit. Die Luftschutzeinrichtungen der Stadt haben sich ebenso bewährt, wie die Luftschutzdisziplin der Bevölkerung. Bis zur Stunde sind 26 Gefallene gemeldet, deren Zahl sich aller Voraussicht nach nicht wesentlich erhöhen dürfte. Die Hilfsmaßnahmen haben unter Führung der Partei und tatkräftigen Mitarbeit der Wehrmacht sofort und wirkungsvoll eingesetzt.

Diese durch Zensur und Gleichschaltung der Medien fantasievoll gestaltete Nachricht schaffte es gerade mal auf Seite 3. Prominenter wollte man die schlechte Vorbereitung der Stadt auf das absehbare Bombardement wohl nicht dem Volkskörper präsentieren. Ganz so groß wie 1938 nach dem Anschluss, als Hitler am 5. April von 100.000 Menschen in Innsbruck begeistert empfangen worden war, war die Begeisterung für den Nationalsozialismus nicht mehr. Zu groß waren die Schäden an der Stadt und die persönlichen, tragischen Verluste in der Bevölkerung. Dass die sterblichen Überreste der Opfer des Luftangriffes vom 15. Dezember 1943 am heutigen Landhausplatz vor dem neu errichteten Gauhaus als Symbol nationalsozialistischer Macht im Stadtbild aufgebahrt wurden, zeugt von trauriger Ironie des Schicksals.

Im Jänner 1944 begann man Luftschutzstollen und andere Schutzmaßnahmen zu errichten. Die Arbeiten wurden zu einem großen Teil von Gefangenen des Konzentrationslagers Reichenau durchgeführt. Insgesamt wurde Innsbruck zwischen 1943 und 1945 zweiundzwanzig Mal angegriffen. Dabei wurden knapp 3833, also knapp 50%, der Gebäude in der Stadt beschädigt und 504 Menschen starben. In den letzten Kriegsmonaten war an Normalität nicht mehr zu denken. Die Bevölkerung lebte in dauerhafter Angst. Die Schulen wurden bereits vormittags geschlossen. An einen geregelten Alltag war nicht mehr zu denken. Die Stadt wurde zum Glück nur Opfer gezielter Angriffe. Deutsche Städte wie Hamburg oder Dresden wurden von den Alliierten mit Feuerstürmen mit Zehntausenden Toten innerhalb weniger Stunden komplett dem Erdboden gleichgemacht. Viele Gebäude wie die Jesuitenkirche, das Stift Wilten, die Servitenkirche, der Dom, das Hallenbad in der Amraserstraße wurden getroffen. Besondere Behandlung erfuhren während der Angriffe historische Gebäude und Denkmäler. Das Goldene Dachl was protected with a special construction, as was Maximilian's sarcophagus in the Hofkirche. The figures in the Hofkirche, the Schwarzen Mannder, wurden nach Kundl gebracht. Die Madonna Lucas Cranachs aus dem Innsbrucker Dom wurde während des Krieges ins Ötztal überführt.

Der Luftschutzstollen südlich von Innsbruck an der Brennerstraße und die Kennzeichnungen von Häusern mit Luftschutzkellern mit ihren schwarzen Vierecken und den weißen Kreisen und Pfeilen kann man heute noch begutachten. Zwei der Stellungen der Flugabwehrgeschütze, mittlerweile nur noch zugewachsene Mauerreste, können am Lanser Köpfl oberhalb von Innsbruck besichtigt werden. In Pradl, wo neben Wilten die meisten Gebäude beschädigt wurden, weisen an den betroffenen Häusern Bronzetafeln mit dem Hinweis auf den Wiederaufbau auf einen Bombentreffer hin.

Innsbruck and National Socialism

In the 1920s and 30s, the NSDAP also grew and prospered in Tyrol. The first local branch of the NSDAP in Innsbruck was founded in 1923. With "Der Nationalsozialist - Combat Gazette for Tyrol and Vorarlberg“ published its own weekly newspaper. In 1933, the NSDAP also experienced a meteoric rise in Innsbruck with the tailwind from Germany. The general dissatisfaction and disenchantment with politics among the citizens and theatrically staged torchlight processions through the city, including swastika-shaped bonfires on the Nordkette mountain range during the election campaign, helped the party to make huge gains. Over 1800 Innsbruck residents were members of the SA, which had its headquarters at Bürgerstraße 10. While the National Socialists were only able to win 2.8% of the vote in their first municipal council election in 1921, this figure had already risen to 41% by the 1933 elections. Nine mandataries, including the later mayor Egon Denz and the Gauleiter of Tyrol Franz Hofer, were elected to the municipal council. It was not only Hitler's election as Reich Chancellor in Germany, but also campaigns and manifestations in Innsbruck that helped the party, which had been banned in Austria since 1934, to achieve this result. As everywhere else, it was mainly young people in Innsbruck who were enthusiastic about National Socialism. They were attracted by the new, the clearing away of old hierarchies and structures such as the Catholic Church, the upheaval and the unprecedented style. National Socialism was particularly popular among the big German-minded lads of the student fraternities and often also among professors.

When the annexation of Austria to Germany took place in March 1938, civil war-like scenes ensued. Already in the run-up to the invasion, there had been repeated marches and rallies by the National Socialists after the ban on the party had been lifted. Even before Federal Chancellor Schuschnigg gave his last speech to the people before handing over power to the National Socialists with the words "God bless Austria" had closed on 11 March 1938, the National Socialists were already gathering in the city centre to celebrate the invasion of the German troops. The police of the corporative state were partly sympathetic to the riots of the organised manifestations and partly powerless in the face of the goings-on. Although the Landhaus and Maria-Theresien-Straße were cordoned off and secured with machine-gun posts, there was no question of any crackdown by the executive. "One people - one empire - one leader" echoed through the city. The threat of the German military and the deployment of SA troops dispelled the last doubts. More and more of the enthusiastic population joined in. At the Tiroler Landhaus, then still in Maria-Theresienstraße, and at the provisional headquarters of the National Socialists in the Gasthaus Old Innspruggthe swastika flag was hoisted.

On 12 March, the people of Innsbruck gave the German military a frenetic welcome. To ensure hospitality towards the National Socialists, Mayor Egon Denz had each worker paid a week's wages. On 5 April, Adolf Hitler personally visited Innsbruck to be celebrated by the crowd. Archive photos show a euphoric crowd awaiting the Führer, the promise of salvation. Mountain fires in the shape of swastikas were lit on the Nordkette. The referendum on 10 April resulted in a vote of over 99% in favour of Austria's annexation to Germany. After the economic hardship of the interwar period, the economic crisis and the governments under Dollfuß and Schuschnigg, people were tired and wanted change. What kind of change was initially less important than the change itself. "Showing them up there", that was Hitler's promise. The Wehrmacht and industry offered young people a perspective, even those who had little to do with the ideology of National Socialism in and of itself. The fact that there were repeated outbreaks of violence was not unusual for the interwar period in Austria anyway. Unlike today, democracy was not something that anyone could have got used to in the short period between the monarchy in 1918 and the elimination of parliament under Dollfuß in 1933, which was characterised by political extremes. There is no need to abolish something that does not actually exist in the minds of the population.

Tyrol and Vorarlberg were combined into a Reichsgau with Innsbruck as its capital. Even though National Socialism was viewed sceptically by a large part of the population, there was hardly any organised or even armed resistance, as the Catholic resistance OE5 and the left in Tyrol were not strong enough for this. There were isolated instances of unorganised subversive behaviour by the population, especially in the arch-Catholic rural communities around Innsbruck. The power apparatus dominated people's everyday lives too comprehensively. Many jobs and other comforts of life were tied to an at least outwardly loyal attitude to the party. The majority of the population was spared imprisonment, but the fear of it was omnipresent.

The regime under Hofer and Gestapo chief Werner Hilliges also did a great job of suppression. In Tyrol, the church was the biggest obstacle. During National Socialism, the Catholic Church was systematically combated. Catholic schools were converted, youth organisations and associations were banned, monasteries were closed, religious education was abolished and a church tax was introduced. Particularly stubborn priests such as Otto Neururer were sent to concentration camps. Local politicians such as the later Innsbruck mayors Anton Melzer and Franz Greiter also had to flee or were arrested. It would go beyond the scope of this article to summarise the violence and crimes committed against the Jewish population, the clergy, political suspects, civilians and prisoners of war. The Gestapo headquarters were located at Herrengasse 1, where suspects were severely abused and sometimes beaten to death with fists. In 1941, the Reichenau labour camp was set up in Rossau near the Innsbruck building yard. Suspects of all kinds were kept here for forced labour in shabby barracks. Over 130 people died in this camp consisting of 20 barracks due to illness, the poor conditions, labour accidents or executions. Prisoners were also forced to work at the Messerschmitt factory in the village of Kematen, 10 kilometres from Innsbruck. These included political prisoners, Russian prisoners of war and Jews. The forced labour included, among other things, the construction of the South Tyrolean settlements in the final phase or the tunnels to protect against air raids in the south of Innsbruck. In the Innsbruck clinic, disabled people and those deemed unacceptable by the system, such as homosexuals, were forcibly sterilised.

The memorials to the National Socialist era are few and far between. The Tiroler Landhaus with the Liberation Monument and the building of the Old University are the two most striking memorials. The forecourt of the university and a small column at the southern entrance to the hospital were also designed to commemorate what was probably the darkest chapter in Austria's history.