Triumphpforte

Maria-Theresienstrasse 46

Worth knowing

An imperial wedding and an imperial death within just a few days in the summer of 1765 briefly made Innsbruck the center of Europe. The Triumphal Arch (Triumphpforte) commemorates the events that took place in Innsbruck. On August 5, Maria Theresa’s son Leopold married the Spanish princess Maria Ludovica in Innsbruck. For the wedding party arriving from southwestern and eastern Europe, Innsbruck was an ideal meeting point to seal the union, as the former residence city already had experience hosting royal and princely weddings. But this time, everything that could go wrong did go wrong. Despite all efforts, the cultural program in the small city could not match the tastes of the noble society. Innsbruck, despite its glorious past as a residence city, had been little more than a provincial town for nearly 100 years. Unstable weather and the groom’s bout of gastroenteritis dampened the mood. News of the bride’s uncle’s death did not help either. The greatest misfortune came shortly after the wedding: on August 18, the groom’s father, Emperor Francis Stephen I of Habsburg-Lorraine, died of a stroke.

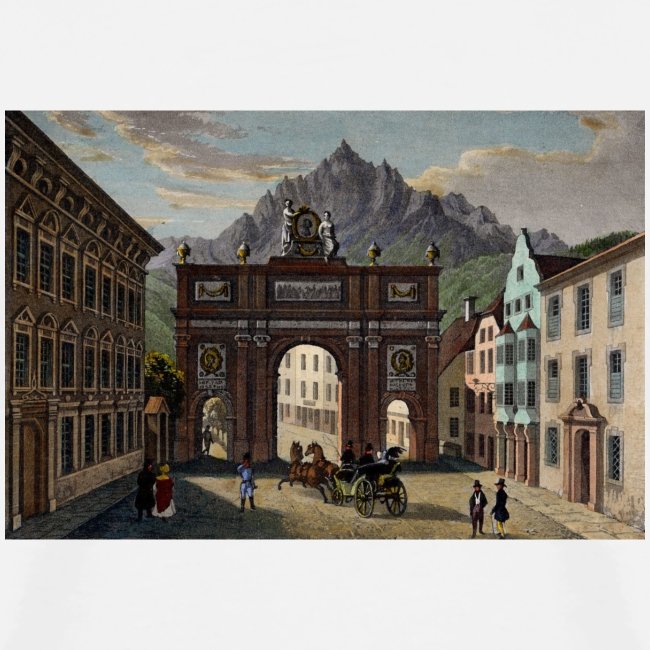

Originally, the wooden arch was intended only as a temporary, festively decorated entrance to the city for the wedding. Reviving the Roman custom of triumphal arches for major events of the imperial family was not unusual. A similar arch had been erected for Emperor Charles VI’s ceremonial entry into the city. In 1774, Maria Theresa had her triumphal arch built permanently in stone, modeled after the ancient Emperor Constantine’s arch, to commemorate both her husband’s death and her son’s wedding forever. The southern side of the arch, facing Leopoldstraße, expresses joy over the wedding of the future Emperor Leopold II. The portrait of the couple is flanked by figures of Providentia Divina (Divine Providence) and Constantia (Constancy). These two virtues were considered essential by the Habsburgs, legitimizing their power over their subjects through divine right, which ensured the stability of the realm for the common good. On the northern side, facing Maria-Theresien-Straße, the angel of death looms in baroque grandeur, symbolizing grief over the emperor’s sudden death. The arch was built using remnants of the city wall and demolition material from the suburban gate at today’s southern Old Town entrance, which had been removed in 1765 during modernization. With the Nordkette mountains to the south, Palais Sarnthein to the west, and the Winklerhaus to the east in the background, the Triumphal Arch today is no longer a memorial to the most disastrous wedding in the city’s history but a stunning photo spot. It’s worth getting up early, as daytime traffic can be quite disruptive if you want to capture a perfect shot.

Maria Theresia, Reformatorin und Landesmutter

Maria Theresia zählt zu den bedeutendsten Figuren der österreichischen Geschichte. Obwohl sie oft als Kaiserin tituliert wird, war sie offiziell "nur" unter anderem Erzherzogin von Österreich, Königin von Ungarn und Königin von Böhmen. Bedeutend waren ihre innenpolitischen Reformen. Viele davon betrafen konkret auch den Alltag der Innsbrucker in merklichem Ausmaß. Gemeinsam mit ihren Beratern Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz, Joseph von Sonnenfels und Wenzel Anton Kaunitz schaffte sie es aus den sogenannten Österreichischen Erblanden einen modernen Staat zu basteln. Anstatt der Verwaltung ihrer Territorien durch den ansässigen Adel setzte sie auf eine moderne Verwaltung. Ihre Berater hatten ganz im Stil der Aufklärung erkannt, dass sich das Staatswohl aus der Gesundheit und Bildungsgrad seiner Einzelteile ergab. Eine frühe Krankenreform Maria Theresias aus dem Jahr 1742 verpflichtete die Professoren des Fachbereichs Medizin an der Universität Innsbruck auch den Betrieb des Stadtspitals in der Neustadt sicherzustellen. Eine Schulreform veränderte die Bildungslandschaft innerhalb der Stadtmauern nicht nur thematisch, sondern auch örtlich. Untertanen sollten katholisch sein, ihre Treue aber sollte dem Staat gelten. Schulbildung wurde unter zentrale staatliche Verwaltung gestellt. Es sollten keine kritischen, humanistischen Geistesgrößen, sondern Material für den staatlichen Verwaltungsapparat erzogen werden. Über Militär und Verwaltung konnten nun auch Nichtadlige in höhere staatliche Positionen aufsteigen. Gleichzeitig sollten Reformen im Staatsdienst und in der Wirtschaft nicht nur mehr Möglichkeiten für die Untertanen schaffen, sondern auch die Staatseinnahmen erhöhen. Gewichte und Maßeinheiten wurden nominiert, um das Steuersystem undurchlässiger zu machen. Für Bürger und Bauern hatte die Vereinheitlichung der Gesetze den Vorteil, dass das Leben weniger von Grundherren und deren Launen abhing. Auch der Robot, den Bauern auf den Gütern des Grundherrn kostenfrei zu leisten hatten, wurde unter Maria Theresia abgeschafft. In Strafverfolgung und Justiz fand ein Umdenken statt. 1747 wurde in Innsbruck eine kleine Polizei which was responsible for matters relating to market supervision, trade regulations, tourist control and public decency. The penal code Constitutio Criminalis Theresiana did not abolish torture, but it did regulate its use.

As much as Maria Theresa staged herself as a pious mother of the country and is known today as an Enlightenment figure, the strict Catholic ruler was not squeamish when it came to questions of power and religion. In keeping with the trend of the Enlightenment, she had superstitions such as vampirism, which was widespread in the eastern parts of her empire, critically analysed and initiated the final end to witch trials. At the same time, however, she mercilessly expelled Protestants from the country. Many Tyroleans were forced to leave their homeland and settle in parts of the Habsburg Empire further away from the centre.

In crown lands such as Tyrol, Maria Theresa's reforms met with little favour. With the exception of a few liberals, they saw themselves more as an independent and autonomous province and less as part of a modern territorial state. The clergy also did not like the new, subordinate role, which became even more pronounced under Joseph II. For the local nobility, the reforms not only meant a loss of importance and autonomy, but also higher taxes and duties. Taxes, levies and customs duties, which had always provided the city of Innsbruck with reliable income, were now collected centrally and only partially refunded via financial equalisation. In order to minimise the fall of sons from impoverished aristocratic families and train them for civil service, Maria Theresa founded the Theresianum, das ab 1775 auch in Innsbruck eine Niederlassung hatte. Wie so oft bügelte die Zeit manche Falte aus und Innsbrucker sind mittlerweile stolz darauf, eine der bedeutendsten Herrscherpersönlichkeiten der österreichischen Geschichte beherbergt zu haben. Heute erinnern die Triumphpfote und die Hofburg in Innsbruck an die Theresianische Zeit.

Holy Roman Empire

The Austrian state is a fairly recent invention, as is citizenship. For more than 1000 years, Innsbruck was a land of the Heiligen Römischen Reiches. Innsbruckers were subjects of the emperor. And subjects of the Tyrolean sovereign. And their landlord. If they had citizenship, they were also Innsbruckers. And very probably also Christians. What they were not, at least not until 1806, was Austrian. But what was this Holy Roman Empire? And who was the emperor? And was he really more powerful than the king?

The empire was a union of individual countries, characterised by conflicts and squabbles over power, both between the princes of the empire and between the princes and the emperor. It had no capital. The centre of the empire was where the emperor was, who kept changing his residences. Emperor Maximilian I made Innsbruck one of his residence cities, which was like a turbo boost for the city's development. Until the 19th century, nationality and perceived affiliation played less of a role in nationality than they do today.

Christianity was the bond that held many things together. Institutions such as the Imperial Chamber Court or the Imperial Diet were only introduced in the late Middle Ages and early modern period to facilitate administration and settle disputes between the individual sovereigns. The Goldene Bulle, die unter anderem die Wahl des Kaisers regelten, war eine sehr einfache Form einer frühen Verfassung. Drei geistliche und 4 weltliche Kurfürsten wählten ihr Oberhaupt. Im Reichstag hatten die Fürsten Sitz und Stimme, der Kaiser war von ihnen abhängig. Um sich durchzusetzen, bedurfte er einer starken Hausmacht. Die Habsburger konnten dabei unter anderem auf Tirol zurückgreifen. Tirol war immer wieder Zankapfel zwischen den Habsburgern und den Herzögen von Bayern, obwohl beide dem Holy Roman Empire belonged to. Innsbruck was under the administration of Bavarian princely families several times.

Die Hierarchie innerhalb des feudalen Lehensystems war streng geordnet vom Kaiser bis zum Bauern. Kaiser und Könige erhielten Macht und Legitimation direkt von Gott. Das Feudalsystem war gottgewollt. Bauern, mehr als 90% der mittelalterlichen Bevölkerung, arbeiteten am Feld, um den für das Seelenheil betenden Klerus und die für die Schutzlosen kämpfenden und den Klerus beschützende Aristokratie zu ernähren. Es war eine Dreierbeziehung in der eine Seite Ordnung und Gebete für das Seelenheil der Menschheite, eine Seite Schutz, Leib und Leben und die dritte Seite Gehorsam, Treue und Arbeit einbrachten. Dieses Treueverständnis mag uns Staatsbürgern moderner Prägung fremd erscheinen, sind die Pflichten heutzutage über Steuern, der Einhaltung von Gesetzen, Wahlen oder Präsenzdienst abstrakter und wesentlich weniger persönlich. Bis ins 20. Jahrhundert hinein baute das Feudalsystem aber genau darauf auf. Treue basierte nicht wie die heutige Staatsbürgerschaft auf einem Geburtsrecht. Der „österreichische“ Militär Prinz Eugen mag französischer Abstammung gewesen sein, trotzdem kämpfte er in der Armee Leopolds I., des Kaisers des Heiligen Römischen Reiches against France. He was a subject of the Archduke of Austria with residences in Vienna and Hungary. While you had to be born in the USA to become president, the ruler was not bound to an innate nationality. Emperor Charles V was born in what is now Ghent in Belgium, grew up at the Burgundian court, became King of Spain before inheriting the Archduchy of Austria and later being elected Emperor. Germanicus being German did not mean being German, it mostly referred to the everyday language a person used.

Das Römische im Deutschen war ein jahrhundertealtes Konzept. Als Karl der Große im Jahr 800 in Rom zum Römisch-Deutschen Kaiser gekrönt wurde, trat er das Erbe der römischen Kaiser mit göttlicher Legitimation durch die Salbung des Papstes an. und gleichzeitig als weltlicher Schutzherr des Papstes an. Der Kaiser war im Gegenzug die Schutzmacht des Heiligen Vaters auf Erden. Das Heilige Römische Reich unter dem Mantel des Kaisers hörte erst 1806 zu Zeiten der Napoleonischen Kriege auf zu existieren. Zentraleuropa begann sich ab dieser Zeit langsam in eine Ansammlung von Nationalstaaten nach dem Vorbild Frankreichs und Englands zu verwandeln. Die Idee des Roman Empire ging auf die abenteuerliche, antike Vorstellung zurück, dass das antike Rom weiter Bestand haben musste. Für gläubige Christen war es laut der Lehre der Vier Weltreiche of enormous importance that the empire continued to exist. The basis of the Lehre der Vier Weltreiche was the Book of Daniel in the Old Testament. According to this story, the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar dreamed of four successive world empires. According to the prophet, the world would end with the end of the fourth empire. The Christian church father Jerome interpreted these four empires around 400 AD as the succession of Babylon, Persia, Greece and the Roman Empire. In the belief of the Middle Ages, the end of Roman rule also meant the end of the world and therefore Rome could not come to an end. About this so-called Translatio Imperii, also die Übertragung des Rechtsanspruchs des Imperium Romanum der Antike auf die Römisch Deutschen Kaiser nach Karl dem Großen, wurde die Beständigkeit Roms formell gewahrt und die Erde konnte fortbestehen. Dem Kaiser sei Dank, dass es uns heute noch gibt.

Innsbruck and the House of Habsburg

Today, Innsbruck's city centre is characterised by buildings and monuments that commemorate the Habsburg family. For many centuries, the Habsburgs were a European ruling dynasty whose sphere of influence included a wide variety of territories. At the zenith of their power, they were the rulers of a "Reich, in dem die Sonne nie untergeht". Through wars and skilful marriage and power politics, they sat at the levers of power between South America and the Ukraine in various eras. Innsbruck was repeatedly the centre of power for this dynasty. The relationship was particularly intense between the 15th and 17th centuries. Due to its strategically favourable location between the Italian cities and German centres such as Augsburg and Regensburg, Innsbruck was given a special place in the empire at the latest after its elevation to a royal seat under Emperor Maximilian.

Tyrol was a province and, as a conservative region, usually favoured the dynasty. Even after its time as a royal seat, the birth of new children of the ruling family was celebrated with parades and processions, deaths were mourned in memorial masses and archdukes, kings and emperors were immortalised in public spaces with statues and pictures. The Habsburgs also valued the loyalty of their Alpine subjects to the Nibelung. In the 19th century, the Jesuit Hartmann Grisar wrote the following about the celebrations to mark the birth of Archduke Leopold in 1716:

„But what an imposing sight it was when, as night fell, the Abbot of Wilten held the final religious function in front of St Anne's Column, which had been consecrated by the blood of the country, surrounded by rows of students and the packed crowd; when, by the light of thousands of burning lights and torches, the whole town, together with the studying youth, the hope of the country, implored heaven for a blessing for the Emperor's newborn first son.“

Its inaccessible location made it the perfect refuge in troubled and crisis-ridden times. Charles V (1500 - 1558) fled during a conflict with the Protestant Schmalkaldischen Bund to Innsbruck for some time. Ferdinand I (1793 - 1875) allowed his family to stay in Innsbruck, far away from the Ottoman threat in eastern Austria. Shortly before his coronation in the turbulent summer of the 1848 revolution, Franz Josef I enjoyed the seclusion of Innsbruck together with his brother Maximilian, who was later shot by insurgent nationalists as Emperor of Mexico. A plaque at the Alpengasthof Heiligwasser above Igls reminds us that the monarch spent the night here as part of his ascent of the Patscherkofel. Some of the Tyrolean sovereigns from the House of Habsburg had no special relationship with Tyrol, nor did they have any particular affection for this German land. Ferdinand I (1503 - 1564) was educated at the Spanish court. Maximilian's grandson Charles V had grown up in Burgundy. When he set foot on Spanish soil for the first time at the age of 17 to take over his mother Joan's inheritance of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, he did not speak a word of Spanish. When he was elected German Emperor in 1519, he did not speak a word of German.

Not all Habsburgs were happy to be „allowed“ to be in Innsbruck. Married princes and princesses such as Maximilian's second wife Bianca Maria Sforza or Ferdinand II's second wife Anna Caterina Gonzaga were stranded in the harsh, German-speaking mountains after the wedding without being asked. If you also imagine what a move and marriage from Italy to Tyrol to a foreign man meant for a teenager, you can imagine how difficult life was for the princesses. Until the 20th century, children of the aristocracy were primarily brought up to be politically married. There was no opposition to this. One might imagine courtly life to be ostentatious, but privacy was not provided for in all this luxury.

Innsbruck experienced its Habsburg heyday when the city was the main residence of the Tyrolean sovereigns. Ferdinand II, Maximilian III and Leopold V and their wives left their mark on the city during their reigns. When Sigismund Franz von Habsburg (1630 - 1665) died childless as the last sovereign prince, the title of residence city was also history and Tyrol was ruled by a governor. Tyrolean mining had lost its importance and did not require any special attention. Shortly afterwards, the Habsburgs lost their possessions in Western Europe along with Spain and Burgundy, which moved Innsbruck from the centre to the periphery of the empire. In the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy of the 19th century, Innsbruck was the western outpost of a huge empire that stretched as far as today's Ukraine. Franz Josef I (1830 - 1916) ruled over a multi-ethnic empire between 1848 and 1916. However, his neo-absolutist concept of rule was out of date. Although Austria had had a parliament and a constitution since 1867, the emperor regarded this government as "his". Ministers were responsible to the emperor, who was above the government. In the second half of the 19th century, the ailing empire collapsed. On 28 October 1918, the Republic of Czechoslovakia was proclaimed, and on 29 October, Croats, Slovenes and Serbs left the monarchy. The last Emperor Charles abdicated on 11 November. On 12 November, "Deutschösterreich zur demokratischen Republik, in der alle Gewalt vom Volke ausgeht“. The chapter of the Habsburgs was over.

Despite all the national, economic and democratic problems that existed in the multi-ethnic states that were subject to the Habsburgs in various compositions and forms, the subsequent nation states were sometimes much less successful in reconciling the interests of minorities and cultural differences within their territories. Since the eastward enlargement of the EU, the Habsburg monarchy has been seen by some well-meaning historians as a pre-modern predecessor of the European Union. Together with the Catholic Church, the Habsburgs shaped the public sphere through architecture, art and culture. Goldenes DachlThe Hofburg, the Triumphal Gate, Ambras Castle, the Leopold Fountain and many other buildings still remind us of the presence of the most important ruling dynasty in European history in Innsbruck.