Tummelplatz

Above Ambras Castle / Tummelplatz stop

Worth knowing

In the middle of the forest, slightly above Ambras Castle, lies the remarkable burial and memorial site Tummelplatz, which commemorates fallen soldiers from the Napoleonic Wars up to the Second World War. The variously aged and sometimes artistically designed crosses and gravestones tell the fates and stories of soldiers from different eras. The clearing takes its name from the horses of Ambras Castle, which were trained here in front of the castle gates and thus ‘frolicked’ (‘tummelten’).

When the Napoleonic Wars raged in Tyrol from 1796 to 1815, the vacant Ambras Castle was converted into a military hospital. Many of those who died were buried at the Tummelplatz. In 1799, the Amras municipal leader Johann Georg Sokopf placed a sign at the entrance of the burial site in the forest to explicitly designate it as such. During the wars of 1848, 1859, and 1866, Ambras Castle again served as a hospital for the wounded. Soldiers from all crown lands of the vast Habsburg Empire, as well as five nurses who died at Ambras Castle, were buried at the Tummelplatz until 1856. Soon, eerie stories about the soldiers’ cemetery began circulating among the people of Innsbruck. After an apparition of the Virgin Mary and a miraculous healing, the Tummelplatz became a pilgrimage site. The first chapels were soon built. Today, the site serves as a valuable memorial for relatives of war victims who were buried far away on the battlefields of the world wars.

The most striking structure is the Cross Chapel, which was financed through donations in 1897. On October 11 of the year it was built, the Innsbrucker Nachrichten reported:

The most striking building is the Chapel of the Crosswhich was financed by donations in 1897. On 11 October of the year it was built, the Innsbrucker Nachrichten zu lesen:

“On the front side facing the Tummelplatz is the entrance to the chapel in a Gothic pointed arch. A marble plaque above the portal proclaims the dedication of the chapel as a pious remembrance of the warriors who fell in the wars of liberation in 1797 and 1809 and were buried here. The upper part of the gable is adorned with a round window in the shape of a trefoil. The entire front is crowned by a roof turret used as a belfry for two bright-sounding bells, providing a stylistically appropriate finish. … Inside the chapel, on the west wall next to the window, a marble votive plaque is embedded in the masonry, whose inscription recalls the terrible fate that befell Duchess Charlotte Augusta of Alençon during the fire at a charity bazaar in Paris on May 4, 1897.”

The façade was designed in 1917 during the First World War by Anton Kirchner and depicts soldiers from the Italian front pulling a wooden coffin. The Mater Dolorosa, holding the body of Christ in her arms and flanked by riflemen and soldiers, watches over the eerie scene. Below it is a martial poem by Anton Müller (1870–1939), better known as Brother Willram, who contributed to antisemitism, war propaganda, and agitation through his writings and sermons during the First World War. He combined the uprising of 1809, Tyrolean heroism, loyalty to the emperor, and Catholicism in a way that hardly matched the battles of industrialized warfare between 1914 and 1918. The first stanza reads:

„Das war in herrlicher Väterzeit,

Da der Ahne sich dem Tod geweiht,

Als Opfer feindlicher Schergen,

Nun färbte der Enkel in seinem Blut,

den Staub der Väter mit heiliger Glut,

Auf unseren ewigen Bergen.“

During the renovation of the chapel in 1969, Anton Plattner’s painting ‘The Risen Savior Overcomes Death’ was added to the interior. In addition to these two main chapels, the Tummelplatz also features the Sokopf Chapel—named after the Amras municipal leader who officially marked the site—the Lourdes Chapel, the Antonius Chapel, and the Joseph Chapel. Student fraternities, professional guilds, and associations commemorate their fallen members with monuments at the Tummelplatz.

The Tummelplatz is more than a regional memorial site. It serves as an international place of remembrance for war victims and as a monument for the preservation of peace. The various memorials show how much perspectives on war and peace have changed since the times of the First World War, when a population influenced by propaganda was ready to give its life on the field of honor for God, Emperor, and Fatherland. An inscription on a gravestone with an image of the Virgin of Mercy (Mariahilf) by Lucas Cranach reads:

I wore it with honour,

the Kaiserjäger dress of honour,

and was in his younger days,

also willing to die.

To die for the fatherland,

is the soldier's fortune, he will inherit heaven,

and does not want to go back.

So do not weep for your loved ones,

it's well done to me,

and you remained the consolation,

that we will meet again.

It is to be hoped that misguided patriotism expressed on inscriptions such as ‘We are ready to give property and life for the Fatherland’ will forever remain a thing of the past. At Christmas and other holidays, especially on the first Sunday after All Saints’ Day, events are held to commemorate the fallen. Kaiserjäger, Kaiserschützen, politicians, and clergy gather to solemnly call for peace—sometimes under traditions that appear rather bizarre, dressed in historical costumes.

1796 - 1866: Vom Herzen Jesu bis Königgrätz

The period between the French Revolution and the Battle of Königgrätz in 1866 was a period of war. Many of the basic political attitudes, animosities towards other groups and European nationalism of the 19th and 20th centuries, which were also to influence the history of Innsbruck, had their roots in the conflicts of this period. Revolutionary Paris was a long way away and there were neither e-mails nor a nationwide press system to disseminate news. The godlessness of Marie Antoinette's murderers and the hatred of the Church of the new masters of France were successfully spread via leaflets and church pulpits. The monarchies of Europe, led by the Habsburgs, had declared war on the French Republic. Fears were rife that the slogan of the revolution „Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité" could spread across Europe. A young general named Napoleon Bonaparte was with his italienischen Armee advanced across the Alps as part of the coalition wars and met the Austrian troops there. It was not just a war for territory and power, it was a battle of systems. The Grande Armee of the revolutionary French Republic met the troops of the conservative and Catholic Habsburgs.

Tyrolean marksmen were actively involved in the fighting to defend the country's borders against the invading French. The men were used to handling weapons and were considered skilled marksmen. The historian Ludwig Denk put it this way in an essay in 1860:

"...The Tyrolean's main passion is shooting. Early on, the father takes his son hunting. It is not uncommon to see boys running around with loaded rifles, climbing high mountains and shooting birds or squirrels..."

The strength of units such as the Höttinger Schützen, founded in 1796, lay not in open field battles but in guerrilla warfare. They also had a secret weapon on their side against the most advanced and modern army of the time: the Sacred Heart. Since 1719, Jesuit missionaries had been travelling to the furthest side valleys and had successfully established the cult of the Sacred Heart as a unifying element in the fight against pagan customs and Protestantism. Now that they were facing the godless revolutionary French, who had declared war not only on the monarchy but also on the clergy, it was only logical that the Sacred Heart of Jesus would watch over the Tyrolean holy warriors in a protective capacity. In a hopeless situation, the Tyrolean troops renewed their covenant with the Heart of Jesus to ask for protection. Against all odds, the Tyrolean archers were successful in their defence. It was the abbot of Stams Abbey who petitioned the provincial estates to henceforth organise an annual "das Fest des göttlichen Herzens Jesu mit feierlichem Gottesdienst zu begehen, wenn Tirol von der drohenden Feindesgefahr befreit werde." Every year, the Sacred Heart celebrations were discussed and announced with great pomp in the press. In the 19th and early 20th centuries in particular, they were an explosive mixture of popular superstition, Catholicism and national resentment against everything French and Italian. Countless soldiers entrusted their well-being to the heart of Jesus even in the technologised battlefield of the First World War and carried images of this symbol with them in the hail of grenades. Alongside Cranach's Mother of Mercy, the depiction of the Heart of Jesus is probably the most popular Christian motif in Tyrol to this day and is emblazoned on the façades of countless houses.

The Habsburg Tyrol had expanded during the turmoil of war without his involvement, and probably also without that of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Trentino had become part of the crown land in the last breaths of the Holy Roman Empire before its dissolution in 1803. Innsbruck, on the other hand, had shrunk. The deaths of soldiers and the economic difficulties caused by the war led to a decline in the population from a good 9500 around 1750 to around 8800. After the Napoleonic Wars, things remained quiet on the Tyrolean borders for around 30 years. This changed with the Italian Risorgimento, the national movement led by Sardinia-Piedmont and France. 1848, 1859 and 1866 saw the so-called Italian wars of unification. In the course of the 19th century, at the latest since 1848, there was a veritable national frenzy among young men of the upper classes. Volunteer armies sprang up in all regions of Europe. Students and academics who came together in their fraternities, gymnasts, marksmen, all wanted to prove their new love of the nation on the battlefield and supported the official armies.

As a garrison town, Innsbruck was an important supply centre. After the Congress of Vienna, the Tyrolean Jägerkorps the k.k. Tiroler Kaiserjägerregiment an elite unit that was deployed in these conflicts. Volunteer units such as the Innsbruck academics or the Stubai Riflemen fought in Italy. Thousands fell in the fight against the coalition of the arch-enemy France, the godless Garibaldians and the threat posed by the Kingdom of Italy under the leadership of the Francophile Savoys from Piedmont, which was being formed at Austria's expense. The media fuelled the mood away from the front line. The "Innsbrucker Zeitung" predigte in ihren Artikeln Kaisertreue und großdeutsch-tirolischen Nationalismus, wetterte gegen das Italienertum und Franzosen und pries den Mut Tiroler Soldaten.

"Die starke Besetzung der Höhen am Ausgange des Valsugana bei Primolano und le Tezze gab schon oft den Innsbrucker-Akademikern I. und den Stubaiern Anlaß, freiwillige Ercur:sionen gegen le Tezze, Fonzago und Fastro, als auch auf das rechte Brenta-Ufer und den Höhen gegen die kleinen Lager von den Sette comuni zu machen...Am 19. schon haben die Stubaier einige Feinde niedergestreckt, als sie sich das erste mal hinunterwagten, indem sie sich ihnen entgegenschlichen..."

Probably the most famous battle of the Wars of unification took place in Solferino near Lake Garda in 1859. Horrified by the bloody events, Henry Durant decided to found the Red Cross. The writer Joseph Roth described the events in the first pages of his classic book, which is well worth reading Radetzkymarsch.

"In the battle of Solferino, he (note: Lieutenant Trotta) commanded a platoon as an infantry lieutenant. The battle had been going on for half an hour. Three paces in front of him he saw the white backs of his soldiers. The first row of his platoon was kneeling, the second was standing. Everyone was cheerful and certain of victory. They had eaten copiously and drunk brandy at the expense and in honour of the emperor, who had been in the field since yesterday. Here and there one fell out of line."

The year 1866 was particularly costly for the Austrian Empire, with the loss of Veneto and Lombardy in Italy. At the same time, Prussia took the lead in the German Confederation, the successor organisation to the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. For Innsbruck, the withdrawal of the Habsburg Monarchy from the German Confederation meant that it had finally become a city on the western periphery of the empire. The tendency towards so-called Großdeutschen LösungThe German question, i.e. statehood together with the German Empire instead of the independent Austrian Empire, was very pronounced in Innsbruck. The extent to which this German question divided the city became apparent over 30 years later, when the Innsbruck municipal council voted in favour of the Iron Chancellor Bismarck, who was responsible for the fratricidal war between Austria and Germany, wanted to dedicate a street to him. While conservatives loyal to the emperor were horrified by this proposal, the Greater German liberals around Mayor Wilhelm Greil were enthusiastic.

With the Tummelplatz, the Pradl military cemetery and the Kaiserjägermuseum on Mount Isel, the city has several memorials to these bloody conflicts, in which many Innsbruck residents took to the field.

The First World War

It was almost not Gavrilo Princip, but a student from Innsbruck who changed the fate of the world. It was thanks to chance that the 20-year-old Serb was stopped in 1913 because he bragged to a waitress that he was planning to assassinate the heir to the throne. It was only when the world-changing shooting in Sarajevo actually took place that an article about it appeared in the media. After the actual assassination of Franz Ferdinand on 28 June, it was impossible to foresee what impact the First World War that broke out as a result would have on the world and people's everyday lives. However, two days after the assassination of the Habsburg in Sarajevo, the Innsbrucker Nachrichten already prophetic: "We have reached a turning point - perhaps the "turning point" - in the fortunes of this empire".

Enthusiasm for the war in 1914 was also high in Innsbruck. From the "Gott, Kaiser und VaterlandDriven by the "spirit of the times", most people unanimously welcomed the attack on Serbia. Politicians, the clergy and the press joined in the general rejoicing. In addition to the imperial appeal "To my peoples", which appeared in all the media of the empire, the Innsbrucker Nachrichten On 29 July, the day after Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, the media published an article about the capture of Belgrade by Prince Eugene in 1717. The tone in the media was celebratory, although not entirely without foreboding of what was to come.

"The Emperor's appeal to his people will be deeply felt. The internal strife has been silenced and the speculations of our enemies about unrest and similar things have been miserably put to shame. Above all, the Germans stand by the Emperor and the Empire in their old and well-tried loyalty: this time, too, they are ready to stand up for dynasty and fatherland with their blood. We are facing difficult days; no one can even guess what fate will bring us, what it will bring to Europe, what it will bring to the world. We can only trust with our old Emperor in our strength and in God and cherish the confidence that, if we find unity and stick together, we must be granted victory, for we did not want war and our cause is that of justice!"

Theologians such as Joseph Seeber (1856 - 1919) and Anton Müllner alias Bruder Willram (1870 - 1919) who, with her sermons and writings such as "Das blutige Jahr" elevated the war to a crusade against France and Italy.

Many Innsbruckers volunteered for the campaign against Serbia, which was thought to be a matter of a few weeks or months. Such a large number of volunteers came from outside the city to join the military commissions that Innsbruck was almost bursting at the seams. Nobody could have guessed how different things would turn out. Even after the first battles in distant Galicia, it was clear that it would not be a matter of months. Kaiserjäger and other Tyrolean troops were literally burnt out. Poor equipment, a lack of supplies and the catastrophic leadership of the high command under Konrad von Hötzendorf led to the deaths of thousands or to captivity, where hunger, abuse and forced labour awaited them.

In 1915, the Kingdom of Italy entered the war on the side of France and England. This meant that the front went right through what was then Tyrol. From the Ortler in the west across northern Lake Garda to the Sextener Dolomiten the battles of the mountain war took place. Innsbruck was not directly affected by the fighting. However, the war could at least be heard as far as the provincial capital, as was reported in the newspaper of 7 July 1915:

„Bald nach Beginn der Feindseligkeiten der Italiener konnte man in der Gegend der Serlesspitze deutlich Kanonendonner wahrnehmen, der von einem der Kampfplätze im Süden Tirols kam, wahrscheinlich von der Vielgereuter Hochebene. In den letzten Tagen ist nun in Innsbruck selbst und im Nordosten der Stadt unzweifelhaft der Schall von Geschützdonner festgestellt worden, einzelne starke Schläge, die dumpf, nicht rollend und tönend über den Brenner herüberklangen. Eine Täuschung ist ausgeschlossen. In Innsbruck selbst ist der Donner der Kanonen schwerer festzustellen, weil hier der Lärm zu groß ist, es wurde aber doch einmal abends ungefähr um 9 Uhr, als einigermaßen Ruhe herrschte, dieser unzweifelhafte von unseren Mörsern herrührender Donner gehört.“

Until the transfer of regular troops from the Eastern Front to the Tyrolean borders, the national defence depended on the Standschützen, a troop made up of men under 21, over 42 or unfit for regular military service. The casualty figures were correspondingly high.

Although the front was relatively far away from Innsbruck, the war also penetrated civilian life. Due to the mass mobilisation of a large part of the working male population, many businesses came to a complete standstill. Shelves in shops remained empty, public transport came to a standstill, craftsmen and labourers were missing everywhere. There was often a shortage of coal and firewood. Hunger and cold became bitter enemies of women, children, the wounded and those unfit for war in the city. This experience of the total involvement of society as a whole was new to the people. Barracks were erected in the Höttinger Au to house prisoners of war. Transports of wounded brought such a large number of horribly injured people that many civilian buildings such as the university library, which was currently under construction, or Ambras Castle were converted into military hospitals. The Pradl military cemetery was established to cope with the large number of fallen soldiers. A predecessor to tram line 3 was set up to transport the wounded from the railway station to the new garrison hospital, today's Conrad barracks in Pradl. The companies that were still able to produce were subordinated to the war economy. However, the longer the war lasted, the fewer there were. By the winter of 1917, Innsbruck's economy had almost completely collapsed.

As the war drew to a close, so did the front. In February 1918, the Italian air force managed to drop three bombs on Innsbruck. In this winter, which was known as Hunger winter When the war went down in European history, the shortages also made themselves felt. In the final years of the war, food was supplied via ration coupons. 500 g of meat, 60 g of butter and 2 kg of potatoes were the basic diet per person - per week, mind you. Archive photos show the long queues of desperate and hungry people outside the food shops. There were repeated protests and strikes. Politicians, trade unionists, workers and war returnees saw their chance for change. Under the motto Peace, bread and the right to vote a wide variety of parties united in resistance to the war. At this time, most people were already aware that the war was lost and what fate awaited Tyrol, as this article from 6 October 1918 shows:

„Aeußere und innere Feinde würfeln heute um das Land Andreas Hofers. Der letzte Wurf ist noch grausamer; schändlicher ist noch nie ein freies Land geschachert worden. Das Blut unserer Väter, Söhne und Brüder ist umsonst geflossen, wenn dieser schändliche Plan Wirklichkeit werden soll. Der letzte Wurf ist noch nicht getan. Darum auf Tiroler, zum Tiroler Volkstag in Brixen am 13. Oktober 1918 (nächsten Sonntag). Deutscher Boden muß deutsch bleiben, Tiroler Boden muß tirolisch bleiben. Tiroler entscheidet selbst über Eure Zukunft!“

On 4 November, Austria-Hungary and the Kingdom of Italy finally agreed an armistice. This gave the Allies the right to occupy areas of the monarchy. The very next day, Bavarian troops entered Innsbruck. Austria's ally Germany was still at war with Italy and was afraid that the front could be moved closer to the German Reich in North Tyrol. Fortunately for Innsbruck and the surrounding area, however, Germany also surrendered a week later on 11 November. This meant that the major battles between regular armies did not take place.

Nevertheless, Innsbruck was in danger. Huge columns of military vehicles, trains full of soldiers and thousands of emaciated soldiers making their way home from the front on foot passed through the city. Those who could, jumped on one of the overcrowded trains or a car to leave the Brenner Pass behind them to get home. In November 1918, more than 270 soldiers lost their lives during these daring manoeuvres or had to be admitted to one of the city's military hospitals. The city not only had to keep its own citizens in check and guarantee rations, but also protect itself from looting. In order to maintain public order, the Tyrolean National Council formed a People's Army on 5 November made up of schoolchildren, students, workers and citizens. On 23 November 1918, Italian troops occupied the city and the surrounding area. Mayor Greil's appeasement to the people of Innsbruck to surrender the city without rioting was successful. 5000 men had to find shelter in the starving and miserable city. Schools were turned into barracks. Although there were isolated riots, hunger riots and looting, there were no armed clashes with the occupying troops or even a Bolshevik revolution as in Munich.

Over 1200 Innsbruck residents lost their lives on the battlefields and in military hospitals, over 600 were wounded. Memorials to the First World War and its victims can be found in Innsbruck, particularly at churches and cemeteries. The Kaiserjägermuseum on Mount Isel displays uniforms, weapons and pictures of the battle. Streets in Innsbruck are dedicated to the two theologians Anton Müllner and Josef Seeber. A street was also named after the commander-in-chief of the Imperial and Royal Army on the Southern Front, Archduke Eugene. There is a memorial to the unsuccessful commander in front of the Hofgarten. The eastern part of the Amras military cemetery commemorates the Italian occupation.

Andreas Hofer and the Tyrolean uprising of 1809

The Napoleonic Wars gave the province of Tyrol a national epic and, in Andreas Hofer, a hero whose splendour still shines today. However, if one subtracts the carefully constructed legend of the Tyrolean uprising against foreign rule, the period before and after 1809 was a dark chapter in Innsbruck's history, characterised by economic hardship, the devastation of war and several instances of looting. The Kingdom of Bavaria was allied with France during the Napoleonic Wars and was able to take over the province of Tyrol from the Habsburgs in several battles between 1796 and 1805. Innsbruck was no longer the capital of a crown land, but just one of many district capitals of the administrative unit Innkreis. Revenues from tolls and customs duties as well as from Hall salt left the country for the north. The British colonial blockade against Napoleon meant that Innsbruck's long-distance trade and transport industry, which had always flourished and brought prosperity, collapsed. Innsbruck's citizens had to accommodate Bavarian soldiers in their homes. The abolition of the Tyrolean provincial government, the gubernium and the Tyrolean parliament meant not only the loss of status, but also of jobs and financial resources. Inspired by the spirit of the Enlightenment, reason and the French Revolution, the new rulers set about overturning the traditional order. While the city suffered financially as a result of the war, as is always the case, the upheaval opened up new socio-political opportunities. War is the father of all things, The breath of fresh air was not inconvenient for many citizens. Modern laws such as the Alley cleaning order or compulsory smallpox immunisation were intended to promote cleanliness and health in the city. At the beginning of the 19th century, a considerable number of people were still dying from diseases caused by a lack of hygiene and contaminated drinking water. A new tax system was introduced and the powers of the nobility were further reduced. The Bavarian administration allowed associations, which had been banned in 1797, again. Liberal Innsbruckers also liked the fact that the church was pushed out of the education system. The Benedictine priest and later co-founder of the Innsbruck Music Society, Martin Goller, was appointed to Innsbruck to promote musical education.

Diese Reformen behagten einem großen Teil der Tiroler Bevölkerung nicht. Katholische Prozessionen und religiöse Feste fielen dem aufklärerischen Programm der neuen Landesherren zum Opfer. 1808 wurde vom bayerischen König für seinen gesamten Herrschaftsbereich das Gemeindeedikt eingeführt. Die Untertanen wurden darin verpflichtet öffentliche Gebäude, Brunnen, Wege, Brücken und andere Infrastruktur in Stand zu halten. Für die Tiroler Bauern, die seit Jahrhunderten von Fronarbeit größtenteils befreit waren, bedeutete das eine zusätzliche Belastung und war ein Affront gegen ihren Standesstozl. Der Funke, der das Pulverfass zur Explosion brachte, war die Aushebung junger Männer zum Dienst in der bayrisch-napoleonischen Armee, obwohl Tiroler seit dem LandlibellThe law of Emperor Maximilian stipulated that soldiers could only be called up for the defence of their own borders. On 10 April, there was a riot during a conscription in Axams near Innsbruck, which ultimately led to an uprising. For God, Emperor and Fatherland Tyrolean defence units came together to drive the small army and the Bavarian administrative officials out of Innsbruck. The riflemen were led by Andreas Hofer (1767 - 1810), an innkeeper, wine and horse trader from the South Tyrolean Passeier Valley near Meran. He was supported not only by other Tyroleans such as Father Haspinger, Peter Mayr and Josef Speckbacher, but also by the Habsburg Archduke Johann in the background.

Once in Innsbruck, the marksmen not only plundered official facilities. As with the peasants' revolt under Michael Gaismair, their heroism was fuelled not only by adrenaline but also by alcohol. The wild mob was probably more damaging to the city than the Bavarian administrators had been since 1805, and the "liberators" rioted violently, particularly against middle-class ladies and the small Jewish population of Innsbruck.

In July 1809, Bavaria and the French took control of Innsbruck following the agreement with the Habsburgs. Peace of Znojmo, which many still regard as a Viennese betrayal of the province of Tyrol. What followed was what is known as Tyrolean survey under Andreas Hofer, who had meanwhile assumed supreme command of the Tyrolean defence forces, was to go down in the history books. The Tyrolean insurgents were able to carry victory from the battlefield a total of three times. The 3rd battle in August 1809 on Mount Isel is particularly well known. "Innsbruck sees and hears what it has never heard or seen before: a battle of 40,000 combatants...“ For a short time, Andreas Hofer was Tyrol's commander-in-chief in the absence of regular facts, also for civil affairs. Innsbruck's financial plight did not change. Instead of the Bavarian and French soldiers, the townspeople now had to house and feed their compatriots from the peasant regiment and pay taxes to the new provincial government. The city's liberal and wealthy elites in particular were not happy with the new city rulers. The decrees issued by him as provincial commander were more reminiscent of a theocracy than a 19th century body of laws. Women were only allowed to go out on the streets wearing chaste veils, dance events were banned and revealing monuments such as the one on the Leopoldsbrunnen nymphs on display were banned from public spaces. Educational agendas were to return to the clergy. Liberals and intellectuals were arrested, but the Praying the rosary zum Gebot. Am Ende gab es im Herbst 1809 in der vierten und letzten Schlacht am Berg Isel eine empfindliche Niederlage gegen die französische Übermacht. Die Regierung in Wien hatte die Tiroler Aufständischen vor allem als taktischen Prellbock im Krieg gegen Napoleon benutzt. Bereits zuvor hatte der Kaiser das Land Tirol offiziell im Friedensvertrag von Schönbrunn wieder abtreten müssen. Innsbruck war zwischen 1810 und 1814 wieder unter bayrischer Verwaltung. Auch die Bevölkerung war nur noch mäßig motiviert, Krieg zu führen. Wilten wurde von den Kampfhandlungen stark in Mitleidenschaft gezogen. Das Dorf schrumpfte von über 1000 Einwohnern auf knapp 700. Hofer selbst war zu dieser Zeit bereits ein von der Belastung dem Alkohol gezeichneter Mann. Er wurde gefangengenommen und am 20. Januar 1810 in Mantua hingerichtet. Zu allem Überfluss wurde das Land geteilt. Das Etschtal und das Trentino wurden Teil des von Napoleon aus dem Boden gestampften Königreich Italien, das Pustertal wurde den französisch kontrollierten Illyrian provinces connected.

Der „Fight for freedom" symbolises the Tyrolean self-image to this day. For a long time, Andreas Hofer, the innkeeper from the South Tyrolean Passeier Valley, was regarded as an undisputed hero and the prototype of the Tyrolean who was brave, loyal to his fatherland and steadfast. The underdog who fought back against foreign superiority and unholy customs. In fact, Hofer was probably a charismatic leader, but politically untalented and conservative-clerical, simple-minded. His tactics at the 3rd Battle of Mount Isel "Do not abandon them“ (Ann.: Ihr dürft sie nur nicht heraufkommen lassen) fasst sein Wesen wohl ganz gut zusammen. In konservativen Kreisen Tirols wie den Schützen wird Hofer unkritisch und kultisch verehrt. Das Tiroler Schützenwesen ist gelebtes Brauchtum, das sich zwar modernisiert hat, in vielen dunklen Winkeln aber noch reaktionär ausgerichtet ist. Wiltener, Amraser, Pradler und Höttinger Schützen marschieren immer noch einträchtig neben Klerus, Trachtenvereinen und Marschmusikkapellen bei kirchlichen Prozessionen und schießen in die Luft, um alles Übel von Tirol und der katholischen Kirche fernzuhalten. Über die Stadt verteilt erinnern viele Denkmäler an das Jahr 1809. Die zweite Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts erfuhr eine Heroisierung der Kämpfer, die als deutsches Bollwerk gegen fremde Völkerschaften charakterisiert wurden. Der Berg Isel wurde der Stadt für die Verehrung der Freiheitskämpfer vom Stift Wilten, der katholischen Instanz Innsbrucks, zur Verfügung gestellt. Andreas Hofer und seinen Mitstreitern Josef Speckbacher, Peter Mayer, Pater Haspinger und Kajetan Sweth wurden im Stadtteil Wilten, das in der Zeit des großdeutsch-liberal dominierten Gemeinderats 1904 zu Innsbruck kam und lange unter der Verwaltung des Stiftes gestanden hatte, Straßennamen gewidmet. Das kurze Rote Gassl im alten Kern von Wilten erinnert an die Tiroler Schützen, die, in ihnen wohl fälschlich nachgesagten roten Uniformen, dem siegreichen Feldherrn Hofer nach dem Sieg in der zweiten Berg Isel Schlacht an dieser Stelle in Massen gehuldigt haben sollen. In Tirol wird Andreas Hofer bis heute gerne für alle möglichen Initiativen und Pläne vor den Karren gespannt. Vor allem im Nationalismus des 19. Jahrhunderts berief man sich immer wieder auf den verklärten Helden Andreas Hofer. Hofer wurde über Gemälde, Flugblätter und Schauspiele zur Ikone stilisiert. Aber auch heute noch kann man das Konterfei des Oberschützen sehen, wenn sich Tiroler gegen unliebsame Maßnahmen der Bundesregierung, den Transitbestimmungen der EU oder der FC Wacker gegen auswärtige Fußballvereine zur Wehr setzen. Das Motto lautet dann „Man, it's time!“. Die Legende vom wehrfähigen Tiroler Bauern, der unter Tags das Feld bestellt und sich abends am Schießstand zum Scharfschützen und Verteidiger der Heimat ausbilden lässt, wird immer wieder gerne aus der Schublade geholt zur Stärkung der „echten“ Tiroler Identität. Die Feiern zum Todestag Andreas Hofers am 20. Februar locken bis heute regelmäßig Menschenmassen aus allen Landesteilen Tirols in die Stadt. Erst in den letzten Jahrzehnten setzte eine kritische Betrachtung des erzkonservativen und mit seiner Aufgabe als Tiroler Landeskommandanten wohl überforderten Schützenhauptmanns ein, der angestachelt von Teilen der Habsburger und der katholischen Kirche nicht nur Franzosen und Bayern, sondern auch das liberale Gedankengut der Aufklärung vehement aus Tirol fernhalten wollte.

Believe, Church and Power

Die Fülle an Kirchen, Kapellen, Kruzifixen und Wandmalereien im öffentlichen Raum wirkt auf viele Besucher Innsbrucks aus anderen Ländern eigenartig. Nicht nur Gotteshäuser, auch viele Privathäuser sind mit Darstellungen der Heiligen Familie oder biblischen Szenen geschmückt. Der christliche Glaube und seine Institutionen waren in ganz Europa über Jahrhunderte alltagsbestimmend. Innsbruck als Residenzstadt der streng katholischen Habsburger und Hauptstadt des selbsternannten Heiligen Landes Tirol wurde bei der Ausstattung mit kirchlichen Bauwerkern besonders beglückt. Allein die Dimension der Kirchen umgelegt auf die Verhältnisse vergangener Zeiten sind gigantisch. Die Stadt mit ihren knapp 5000 Einwohnern besaß im 16. Jahrhundert mehrere Kirchen, die in Pracht und Größe jedes andere Gebäude überstrahlte, auch die Paläste der Aristokratie. Das Kloster Wilten war ein Riesenkomplex inmitten eines kleinen Bauerndorfes, das sich darum gruppierte. Die räumlichen Ausmaße der Gotteshäuser spiegelt die Bedeutung im politischen und sozialen Gefüge wider.

Die Kirche war für viele Innsbrucker nicht nur moralische Instanz, sondern auch weltlicher Grundherr. Der Bischof von Brixen war formal hierarchisch dem Landesfürsten gleichgestellt. Die Bauern arbeiteten auf den Landgütern des Bischofs wie sie auf den Landgütern eines weltlichen Fürsten für diesen arbeiteten. Damit hatte sie die Steuer- und Rechtshoheit über viele Menschen. Die kirchlichen Grundbesitzer galten dabei nicht als weniger streng, sondern sogar als besonders fordernd gegenüber ihren Untertanen. Gleichzeitig war es auch in Innsbruck der Klerus, der sich in großen Teilen um das Sozialwesen, Krankenpflege, Armen- und Waisenversorgung, Speisungen und Bildung sorgte. Der Einfluss der Kirche reichte in die materielle Welt ähnlich wie es heute der Staat mit Finanzamt, Polizei, Schulwesen und Arbeitsamt tut. Was uns heute Demokratie, Parlament und Marktwirtschaft sind, waren den Menschen vergangener Jahrhunderte Bibel und Pfarrer: Eine Realität, die die Ordnung aufrecht hält. Zu glauben, alle Kirchenmänner wären zynische Machtmenschen gewesen, die ihre ungebildeten Untertanen ausnützten, ist nicht richtig. Der Großteil sowohl des Klerus wie auch der Adeligen war fromm und gottergeben, wenn auch auf eine aus heutiger Sicht nur schwer verständliche Art und Weise. Verletzungen der Religion und Sitten wurden in der späten Neuzeit vor weltlichen Gerichten verhandelt und streng geahndet. Die Anklage bei Verfehlungen lautete Häresie, worunter eine Vielzahl an Vergehen zusammengefasst wurde. Sodomie, also jede sexuelle Handlung, die nicht der Fortpflanzung diente, Zauberei, Hexerei, Gotteslästerung – kurz jede Abwendung vom rechten Gottesglauben, konnte mit Verbrennung geahndet werden. Das Verbrennen sollte die Verurteilten gleichzeitig reinigen und sie samt ihrem sündigen Treiben endgültig vernichten, um das Böse aus der Gemeinschaft zu tilgen. Bis in die Angelegenheiten des täglichen Lebens regelte die Kirche lange Zeit das alltägliche Sozialgefüge der Menschen. Kirchenglocken bestimmten den Zeitplan der Menschen. Ihr Klang rief zur Arbeit, zum Gottesdienst oder informierte als Totengeläut über das Dahinscheiden eines Mitglieds der Gemeinde. Menschen konnten einzelne Glockenklänge und ihre Bedeutung voneinander unterscheiden. Sonn- und Feiertage strukturierten die Zeit. Fastentage regelten den Speiseplan. Familienleben, Sexualität und individuelles Verhalten hatten sich an den von der Kirche vorgegebenen Moral zu orientieren. Das Seelenheil im nächsten Leben war für viele Menschen wichtiger als das Lebensglück auf Erden, war dies doch ohnehin vom determinierten Zeitgeschehen und göttlichen Willen vorherbestimmt. Fegefeuer, letztes Gericht und Höllenqualen waren Realität und verschreckten und disziplinierten auch Erwachsene.

Während das Innsbrucker Bürgertum von den Ideen der Aufklärung nach den Napoleonischen Kriegen zumindest sanft wachgeküsst wurde, blieb der Großteil der Menschen weiterhin der Mischung aus konservativem Katholizismus und abergläubischer Volksfrömmigkeit verbunden. Religiosität war nicht unbedingt eine Frage von Herkunft und Stand, wie die gesellschaftlichen, medialen und politischen Auseinandersetzungen entlang der Bruchlinie zwischen Liberalen und Konservativ immer wieder aufzeigten. Seit der Dezemberverfassung von 1867 war die freie Religionsausübung zwar gesetzlich verankert, Staat und Religion blieben aber eng verknüpft. Die Wahrmund-Affäre, die sich im frühen 20. Jahrhundert ausgehend von der Universität Innsbruck über die gesamte K.u.K. Monarchie ausbreitete, war nur eines von vielen Beispielen für den Einfluss, den die Kirche bis in die 1970er Jahre hin ausübte. Kurz vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg nahm diese politische Krise, die die gesamte Monarchie erfassen sollte in Innsbruck ihren Anfang. Ludwig Wahrmund (1861 – 1932) war Ordinarius für Kirchenrecht an der Juridischen Fakultät der Universität Innsbruck. Wahrmund, vom Tiroler Landeshauptmann eigentlich dafür ausgewählt, um den Katholizismus an der als zu liberal eingestuften Innsbrucker Universität zu stärken, war Anhänger einer aufgeklärten Theologie. Im Gegensatz zu den konservativen Vertretern in Klerus und Politik sahen Reformkatholiken den Papst nur als spirituelles Oberhaupt, nicht aber als weltlich Instanz, an. Studenten sollten nach Wahrmunds Auffassung die Lücke und die Gegensätze zwischen Kirche und moderner Welt verringern, anstatt sie einzuzementieren. Seit 1848 hatten sich die Gräben zwischen liberal-nationalen, sozialistischen, konservativen und reformorientiert-katholischen Interessensgruppen und Parteien vertieft. Eine der heftigsten Bruchlinien verlief durch das Bildungs- und Hochschulwesen entlang der Frage, wie sich das übernatürliche Gebaren und die Ansichten der Kirche, die noch immer maßgeblich die Universitäten besetzten, mit der modernen Wissenschaft vereinbaren ließen. Liberale und katholische Studenten verachteten sich gegenseitig und krachten immer aneinander. Bis 1906 war Wahrmund Teil der Leo-Gesellschaft, die die Förderung der Wissenschaft auf katholischer Basis zum Ziel hatte, bevor er zum Obmann der Innsbrucker Ortsgruppe des Vereins Freie Schule wurde, der für eine komplette Entklerikalisierung des gesamten Bildungswesens eintrat. Vom Reformkatholiken wurde er zu einem Verfechter der kompletten Trennung von Kirche und Staat. Seine Vorlesungen erregten immer wieder die Aufmerksamkeit der Obrigkeit. Angeheizt von den Medien fand der Kulturkampf zwischen liberalen Deutschnationalisten, Konservativen, Christlichsozialen und Sozialdemokraten in der Person Ludwig Wahrmunds eine ideale Projektionsfläche. Was folgte waren Ausschreitungen, Streiks, Schlägereien zwischen Studentenverbindungen verschiedener Couleur und Ausrichtung und gegenseitige Diffamierungen unter Politikern. Die Los-von-Rom Bewegung des Deutschradikalen Georg Ritter von Schönerer (1842 – 1921) krachte auf der Bühne der Universität Innsbruck auf den politischen Katholizismus der Christlichsozialen. Die deutschnationalen Akademiker erhielten Unterstützung von den ebenfalls antiklerikalen Sozialdemokraten sowie von Bürgermeister Greil, auf konservativer Seite sprang die Tiroler Landesregierung ein. Die Wahrmund Affäre schaffte es als Kulturkampfdebatte bis in den Reichsrat. Für Christlichsoziale war es ein „Kampf des freissinnigen Judentums gegen das Christentum“ in dem sich „Zionisten, deutsche Kulturkämpfer, tschechische und ruthenische Radikale“ in einer „internationalen Koalition“ als „freisinniger Ring des jüdischen Radikalismus und des radikalen Slawentums“ präsentierten. Wahrmund hingegen bezeichnete in der allgemein aufgeheizten Stimmung katholische Studenten als „Verräter und Parasiten“. Als Wahrmund 1908 eine seiner Reden, in der er Gott, die christliche Moral und die katholische Heiligenverehrung anzweifelte, in Druck bringen ließ, erhielt er eine Anzeige wegen Gotteslästerung. Nach weiteren teils gewalttätigen Versammlungen sowohl auf konservativer und antiklerikaler Seite, studentischen Ausschreitungen und Streiks musste kurzzeitig sogar der Unibetrieb eingestellt werden. Wahrmund wurde zuerst beurlaubt, später an die deutsche Universität Prag versetzt.

Auch in der Ersten Republik war die Verbindung zwischen Kirche und Staat stark. Der christlichsoziale, als Eiserner Prälat in die Geschichte eingegangen Ignaz Seipel schaffte es in den 1920er Jahren bis ins höchste Amt des Staates. Bundeskanzler Engelbert Dollfuß sah seinen Ständestaat als Konstrukt auf katholischer Basis als Bollwerk gegen den Sozialismus. Auch nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg waren Kirche und Politik in Person von Bischof Rusch und Kanzler Wallnöfer ein Gespann. Erst dann begann eine ernsthafte Trennung. Glaube und Kirche haben noch immer ihren fixen Platz im Alltag der Innsbrucker, wenn auch oft unbemerkt. Die Kirchenaustritte der letzten Jahrzehnte haben der offiziellen Mitgliederzahl zwar eine Delle versetzt und Freizeitevents werden besser besucht als Sonntagsmessen. Die römisch-katholische Kirche besitzt aber noch immer viel Grund in und rund um Innsbruck, auch außerhalb der Mauern der jeweiligen Klöster und Ausbildungsstätten. Etliche Schulen in und rund um Innsbruck stehen ebenfalls unter dem Einfluss konservativer Kräfte und der Kirche. Und wer immer einen freien Feiertag genießt, ein Osterei ans andere peckt oder eine Kerze am Christbaum anzündet, muss nicht Christ sein, um als Tradition getarnt im Namen Jesu zu handeln.

Theodor Prachensky: Beamter zwischen Kaiser und Republik

From the second half of the 1920s, large housing projects were realised to alleviate the greatest need of the many Innsbruck residents who lived in barracks or with relatives in cramped conditions. Entire new neighbourhoods were built with kindergartens and schools. Sports and leisure centres such as the Tivoli and the municipal indoor swimming pool were built. One of the master builders who made lasting changes to Innsbruck during this period was Theodor Prachensky (1888 - 1970).

As an employee of the Innsbruck building authority between 1913 and 1953, he was responsible for housing and infrastructure projects. The projects he realised are not as spectacular as the mountain stations of his brother-in-law Baumann. Prachensky's buildings, which have stood the test of time, often appear sober and purely functional. However, if you look at his drawings in the Archives of Architecture at the University of Innsbruck, you realise that Prachensky was more of an artist than a technician, as his paintings also prove. Many of his spectacular designs, such as the Sozialdemokratische Volkshaus in der Salurnerstraße, sein Kaiserschützendenkmal oder die Friedens- und Heldenkirche were not realised. Innsbruck is home to the large housing estates of the 1920s and 30s, the Warrior Memorial Chapel at the Pradl cemetery and the old labour office (Note: today a branch of the University of Innsbruck behind the current AMS building in Wilten) many of Prachensky's buildings, which document the contemporary history of the interwar period and the changing political and state influences under which he himself was influenced.

His biography reads like an outline of Austrian history in the early 20th century. Prachensky worked as an architect and civil servant under five different state models. The Austro-Hungarian monarchy was followed by the First Republic, which was replaced by the authoritarian corporative state. In 1938, the country was annexed by Nazi Germany. The Second Republic was proclaimed at the end of the war in 1945.

In 1908, Prachensky graduated from the construction department of the Gewerbeschule Innsbruck, now the HTL. From 1909, he worked partly together with Franz Baumann, whose sister Maria he was to marry in 1913, at the renowned architectural firm Musch & Lun in Merano, at that time also still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In his private life, 1913 was a groundbreaking year for him: Theodor and Maria got married and started the private construction project for their own home Haus Prachensky at Berg Isel Weg 20 and the new family man started work at the Innsbruck City Council under Chief Building Officer Jakob Albert. Instead of having to work his way through the difficult economic situation in the private sector after the war, Prachensky worked in the public sector. The important projects influenced by social democratic ideas could only be started after the first and most difficult post-war years, characterised by inflation and supply shortages. The first was the Schlachthausblock im Saggen zwischen 1922 und 1925. Es folgten mehrere Infrastrukturprojekte wie der Mandelsbergerblock, der Pembaurblock and the kindergarten and secondary school in Pembaurstraße, which were primarily intended for the socially disadvantaged and the working class affected by the war and the post-war period. The labour office designed in 1931 was also an important innovation in the social welfare system. Since the founding of the republic in 1918, the labour office helped to place jobseekers with employers and curb unemployment.

His importance increased again during the economic crisis of the 1930s. Another turning point in Prachensky's career was the next change in Austria's form of government. Despite the shift to the right under Dollfuß, including the banning of the Social Democratic Party in 1933 and the Anschluss in 1938, he was able to remain in the civil service as a senior civil servant. Together with Jakob Albert, Prachensky realised the housing blocks known as the South Tyrolean Settlements under the National Socialists from 1939. Unlike several members of his family, he himself was never a member or supporter of the NSDAP.

His father Josef Prachensky, who went down in Tyrolean history as one of the founders of social democracy, probably had a great influence on his work as an architect and urban planner in line with international social democratically orientated architecture.

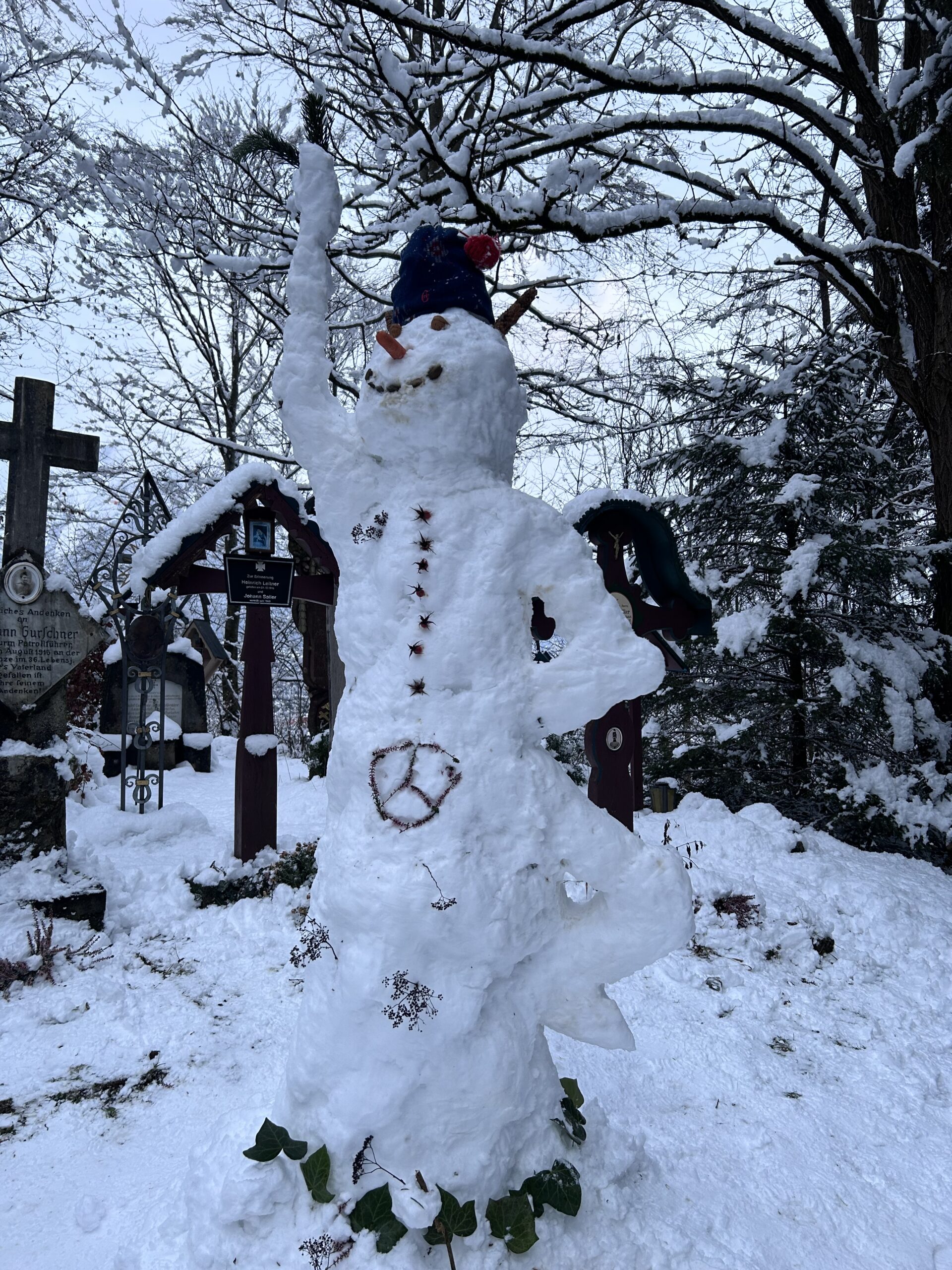

In addition to his father's political views, the disappearance of the Habsburg monarchy and his impressions of military service in the First World War also had an influence on Prachensky. Although he said he was against the war, he volunteered for military service in 1915 as a one-year volunteer with the Tyrolean Kaiserjäger. Perhaps it was the expectations placed on him as a civil servant during the war, perhaps the general enthusiasm that prompted him to take this step, the statements and the deed are contradictory. The war memorial chapel at the Pradl cemetery and the Kaiserschützenkapelle on Tummelplatz, which he designed together with Clemens Holzmeister, as well as his unrealised designs for a Kaiserjäger monument and the Friedens- und Heldenkirche Innsbruckare probably products of Prachensky's life experience.

After the Second World War, he remained active for a further eight years as Chief Planning Officer for the city of Innsbruck. In addition to his work as a construction planner and architect, Prachensky was a keen painter. He died in Innsbruck at the age of 82. His sons, grandsons and great-grandsons continued his creative legacy as architects, designers, photographers and painters in various disciplines. In 2017, parts of the cross-generational work of the Prachensky family of artists were exhibited in the former brewery Adambräu mit einer Ausstellung gezeigt.