HTL Anichstraße

Anichstrasse 26 / 28

Worth knowing

A large part of the buildings constructed in Innsbruck during the 20th century had their origins in a type of school conceived in the 19th century, which continues to produce engineers, master builders, and technicians of all kinds to this day. The Higher Technical Institute (HTL) on Anichstraße not only reflects the bourgeois character of the Gründerzeit in its outward appearance but also illustrates the political and social upheavals of that era in education. The Austro-Hungarian monarchy, though one of the largest states in Europe in the second half of the 19th century, was far from being among the most innovative. Both Emperor Franz Joseph I and many members of the Reichstag were not up to date with the rapid technological developments of the time. Private investors kept things running through their investments in services and infrastructure. Whereas the Fuggers had granted the Emperor generous loans in the 16th century to secure mining rights in Tyrol, modern joint-stock companies obtained concessions for railways and gasworks in return for their engagement. The state welcomed them as partners to advance modernization with fresh capital and ideas. Alongside lucrative profit margins, they also bought political influence. One of their key demands was a reform of the school system. By the time of the Vienna World Exhibition in 1873, it had become clear that education needed to change to prepare young people for an increasingly industrialized world dependent on skilled labor. Humanism and military training could not replace modern vocational education.

The first technical schools in Austria focused on the wood industry. In Innsbruck, however, the State Trade School developed from an artistic environment. The founders and first teachers of the predecessor institution were Johann Deiniger, Heinrich Fuss, and Anton Roux—a sculptor, architect, and landscape painter respectively. Deiniger came to Innsbruck from Vienna in 1876 to work as a technical official at Ambras Castle. The following year, together with Fuss, whom he knew from the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, he founded a drawing and modeling school in the Dreiheiligen elementary school building. They had noticed that Innsbruck’s booming construction and architecture sector needed stronger professionalization. Urban expansion was driven by building firms that often resorted to stylistic copy-paste at clients’ request rather than developing original ideas and considering public needs, creativity, and cost-efficiency. Deiniger and Fuss pushed forward the ambitious project of establishing a k.k. State Trade School in Innsbruck—one of only about 20 in the entire monarchy. The timing was promising: in 1880, the Commercial Academy opened in Saggen to train future banking and finance experts. The following year, construction began on a dedicated building for the planned State Trade School, financed by public funds and the local savings bank, which was also interested in professionalizing the construction industry. Based on plans by Natale Tommasi—later co-designer of the main post office and the military cemetery—the three-story, classically styled building resembling a city palace was erected by Johann Huter & Sons. Its frieze of putti depicts symbols of art, technology, and construction.

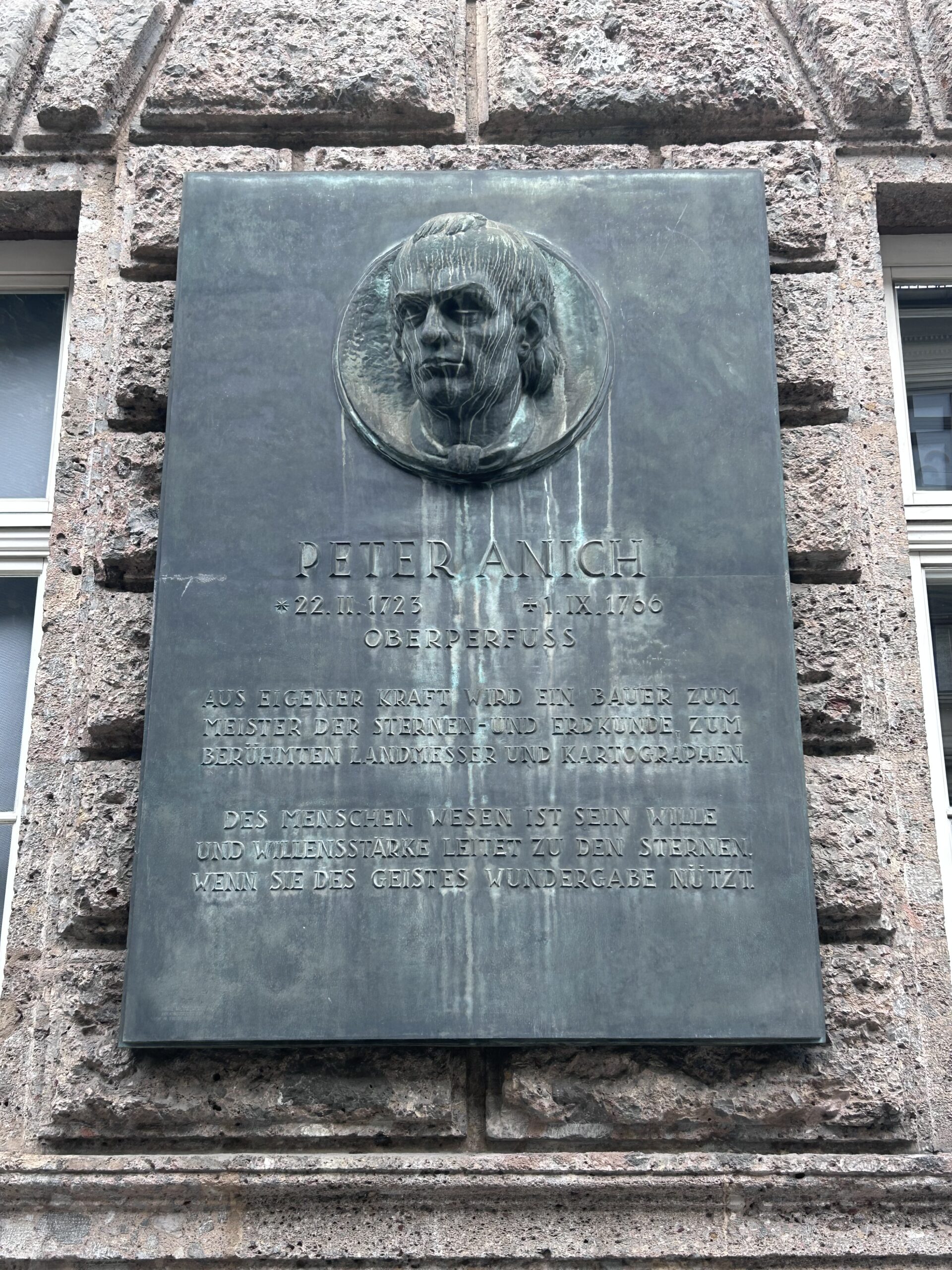

Although Mayor Falk insisted that woodworking should be given ample space in the building, the artistic faction prevailed—unwittingly shaping the cityscape of Innsbruck in the First Republic. In 1882, the School for Construction and Applied Arts opened. Unlike today, students who were not exceptionally talented but lacked means had to pay tuition. While there was a department for wood and metalwork, most teachers came from creative fields. The faculty included architect Deiniger, painter Roux, sculptor Fuss, architect Max Haas, and workshop director Joseph Oppelt. In addition to its construction and applied arts department and workshops, the school offered drawing courses and evening classes for adults in the trades. Student numbers steadily increased. Architecture was considered a golden profession during the late monarchy’s urban boom—much like computer science in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. By 1884, the school was elevated to a k.k. State Trade School. Many of the architects and artists who shaped modern Innsbruck received their training there. In 1910, the building had to be expanded for the first time. Fritz Konzert and Eduard Klingler designed the new four-story structure, which appeared much more restrained and less ornate than the original. It was Konzert’s first major commission in Innsbruck and already hinted at his modern architectural approach. Apart from Jugendstil friezes with geometric figures and ornaments on the top floor, the façade is completely smooth. After World War I, changing requirements under the new state system altered not only the school’s name but also its character. The k.k. State Trade School became the Federal Trade School in the First Republic. In the 1920s, two new branches were added: machine fitting and electrical engineering. Under Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg, the name changed again in 1936 to Peter-Anich-Bundesgewerbeschule, accompanied by a massive bronze plaque bearing the likeness of the school’s namesake. Peter Anich (1723–1766) still gazes sternly at visitors today. The inscription could hardly be more typical of Austria’s conservative corporatist state of the 1930s:

"By his own efforts, a farmer becomes a master of astronomy and geography, a famous surveyor and cartographer. Man's nature is his will and strength of will leads to the stars when it utilises the miraculous gift of the spirit."

After World War II, the school type received its current name: Höhere Technische Lehranstalt (Higher Technical Institute), prominently displayed above the entrance. The growing student numbers of the baby-boom generation made it necessary to split the school in 1973. A modern building was erected in Höttinger Au, now home to the HTL for Construction, Computer Science, and Design. The steadily expanded complex—renovated after a bomb hit in 1944—is now a listed building and extends with a courtyard overbuild to Innrain. Thanks to curricula and branches that continually adapt to technological developments, the HTL will likely continue to produce the city’s future designers under the watchful gaze of Peter Anich.

Article Innsbrucker Nachrichten / 13 February 1882

Moving on to the agenda, the Chairman, Mayor Dr Falk, submitted a motion concerning the establishment of an Imperial and Royal State Trade School in Innsbruck, requesting that he be authorised to make an urgent presentation to the High Government in this matter, so that the original plan for a complete State Trade School would not be thwarted by premature dispositions of the premises in the new school building due to the lack of space that would necessarily arise as a result of these dispositions. In support of his application, he presents a letter from the high governor's office, from which it emerges that the ministry in Vienna intends to allocate and use the premises of the new building for the state trade school to accommodate the departments of this institution, that the same will be used almost exclusively by the Drawing and Modelling School and the Central Institute for the Wood Industry, so that there will be nothing left to accommodate other branches of the building trade, especially the metal industry, and the establishment of both departments will be, if not abandoned, at least pushed into the distant future. However, the town led the construction of the school and the savings bank and the state parliament gave their generous contributions to the construction, only on the condition of a complete trade school. A lengthy debate ensues, in which the municipal councillors, Director Deininger, R. v. Schüllern, Savings Bank Director Dr Tschurtschenthaler, Prof. Hämmerle, Knoll and Mayor Dr Falk take part as applicants. The mayor also reads out a letter from the high government dated 7 May of the previous year, in which the successive development of the school into a complete state trade school is assured; however, he points out that several similar promises have already been made and that the municipality has already made great sacrifices as a result of these promises, e.g. to enable the construction of the chemical laboratory and the justice building, without these government promises having been fulfilled so far

Klingler, Huter, Retter & Co: master builders of expansion

he buildings of the late monarchy still characterise the cityscape of Innsbruck today. The last decades of the 19th century were characterised as Wilhelminian style in the history of Austria. After an economic crisis in 1873, the city began to expand in a revival. From 1880 to 1900, Innsbruck's population grew from 20,000 to 26,000. Wilten, which was incorporated in 1904, tripled in size from 4,000 to 12,000. Between 1850 and 1900, the number of buildings within the city grew from 600 to over 900, most of which were multi-storey apartment blocks, unlike the small buildings of the early modern period. The infrastructure also changed in the course of technical innovations. Gas, water and electricity became part of everyday life for more and more people. The old city hospital gave way to the new hospital. The orphanage and Sieberer's old people's asylum were built in Saggen.

The buildings constructed in the new neighbourhoods were a reflection of this new society. Entrepreneurs, freelancers, employees and workers with political voting rights developed different needs than subjects without this right. From the 1870s, a modern banking system emerged in Innsbruck. Credit institutions such as the Sparkasse, founded in 1821, or the Kreditanstalt, whose building erected in 1910 still stands like a small palace in Maria-Theresien-Straße, not only made it possible to take out loans, but also acted as builders themselves. The apartment blocks that were built also enabled non-homeowners to lead a modern life. Unlike in rural areas of Tyrol, where farming families and their farmhands and maids lived in farmhouses as part of a clan, life in the city came close to the family life we know today. The living space had to correspond to this. The lifestyle of city dwellers demanded multi-room flats and open spaces for relaxation after work. The wealthy middle classes, consisting of entrepreneurs and freelancers, had not yet overtaken the aristocracy, but they had narrowed the gap. They were the ones who not only commissioned private building projects, but also decided on public buildings through their position on the local council.

The 40 years before the First World War were a kind of gold-rush period for construction companies, craftsmen, master builders and architects. The buildings reflected the world view of their clients. Master builders combined several roles and often replaced the architect. Most clients had very clear ideas about what they wanted. They were not to be breathtaking new creations, but copies and references to existing buildings. In keeping with the spirit of the times, the Innsbruck master builders designed the buildings in the styles of historicism and classicism as well as the Tyrolean Heimatstil in accordance with the wishes of the financially strong clients. The choice of style used to build a home was often not only a visual but also an ideological statement by the client. Liberals usually favoured classicism, while conservatives were in favour of the Tyrolean Heimatstil. While the Heimatstil was neo-baroque and featured many paintings, clear forms, statues and columns were style-defining elements in the construction of new classicist buildings. The ideas that people had of classical Greece and ancient Rome were realised in a sometimes wild mix of styles. Not only railway stations and public buildings, but also large apartment blocks and entire streets, even churches and cemeteries were built in this design along the old corridors. The upper middle classes showed their penchant for antiquity with neoclassical façades. Catholic traditionalists had images of saints and depictions of Tyrol's regional history painted on the walls of their Heimatstil houses. While neoclassicism dominates in Saggen and Wilten, most of the buildings in Pradl are in the conservative Heimatstil style.

For a long time, many building experts turned up their noses at the buildings of the upstarts and nouveau riche. Heinrich Hammer wrote in his standard work "Art history of the city of Innsbruck":

"Of course, this first rapid expansion of the city took place in an era that was unfruitful in terms of architectural art, in which architecture, instead of developing an independent, contemporary style, repeated the architectural styles of the past one after the other."

The era of large villas, which imitated the aristocratic residences of days gone by with a bourgeois touch, came to an end after a few wild decades due to a lack of space. Further development of the urban area with individual houses was no longer possible, the space had become too narrow. The area of Falkstrasse / Gänsbachstrasse / Bienerstrasse is still regarded as a neighbourhood today. Villensaggenthe areas to the east as Blocksaggen. In Wilten and Pradl, this type of development did not even occur. Nevertheless, master builders sealed more and more ground in the gold rush. Albert Gruber gave a cautionary speech on this growth in 1907, in which he warned against uncontrolled growth in urban planning and land speculation.

"It is the most difficult and responsible task facing our city fathers. Up until the 1980s (note: 1880), let's say in view of our circumstances, a certain slow pace was maintained in urban expansion. Since the last 10 years, however, it can be said that cityscapes have been expanding at a tremendous pace. Old houses are being torn down and new ones erected in their place. Of course, if this demolition and construction is carried out haphazardly, without any thought, only for the benefit of the individual, then disasters, so-called architectural crimes, usually occur. In order to prevent such haphazard building, which does not benefit the general public, every city must ensure that individuals cannot do as they please: the city must set a limit to unrestricted speculation in the area of urban expansion. This includes above all land speculation."

A handful of master builders and the Innsbruck building authority accompanied this development in Innsbruck. If Wilhelm Greil is described as the mayor of the expansion, the Viennese-born Eduard Klingler (1861 - 1916) probably deserves the title of its architect. Klingler played a key role in shaping Innsbruck's cityscape in his role as a civil servant and master builder. He began working for the state of Tyrol in 1883. In 1889, he joined the municipal building department, which he headed from 1902. In Innsbruck, the commercial academy, the Leitgebule school, the Pradl cemetery, the dermatological clinic in the hospital area, the municipal kindergarten in Michael-Gaismair-Straße, the Trainkaserne (note: today a residential building), the market hall and the Tyrolean State Conservatory are all attributable to Klingler as head of the building department. The Ulrichhaus on Mount Isel, which is now home to the Alt-Kaiserjäger-Club, is a building worth seeing in the Heimatstil style based on his design.

The most important building office in Innsbruck was Johann Huter & Sons. Johann Huter took over his father's brickworks. In 1856, he acquired the first company premises, the Hutergründeon the Innrain. Three years later, the first prestigious headquarters were built in Meranerstraße. The company registration together with his sons Josef and Peter in 1860 marked the official start of the company that still exists today. Huter & Söhne like many of its competitors, saw itself as a complete service provider. The company had its own brickworks, a cement factory, a joinery and a locksmith's shop as well as a planning office and the actual construction company. In 1906/07, the Huters built their own company headquarters at Kaiser-Josef-Straße 15 in the typical style of the last pre-war years. The stately house combines the Tyrolean Heimatstil surrounded by gardens and nature with neo-Gothic and neo-Romanesque elements. Famous from Huter & Söhne buildings erected in Innsbruck include the Monastery of Perpetual Adoration, the parish church of St Nicholas, the first building of the new clinic and several buildings on Claudiaplatz. Shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, the construction company employed more than 700 people.

The second major player was Josef Retter (1872 - 1954). Born in Lower Austria with Tyrolean roots, he completed an apprenticeship as a bricklayer before joining the k.k. State Trade School in Vienna and attended the foreman's school in the building trade department. After gaining professional experience in Vienna, Croatia and Bolzano throughout the Danube Monarchy, he was able to open his own construction company in Innsbruck at the age of 29 thanks to his wife's dowry. Like Huter, his company also included a sawmill, a sand and gravel works and a workshop for stonemasonry work. In 1904, he opened his residential and office building at Schöpfstraße 23a, which is still used today as a Rescuer's house is well known. The dark, neo-Gothic building with its striking bay window with columns and a turret is adorned with a remarkable mosaic depicting an allegory of architecture. The gable relief shows the combination of art and craftsmanship, a symbol of Retter's career. His company was particularly influential in Wilten and Saggen. With the new Academic Grammar School, the castle-like school building for the Commercial Academy, the Evangelical Church of Christ in Saggen, the Zelgerhaus in Anichstraße, the Sonnenburg in Wilten and the neo-Gothic Mentlberg Castle on Sieglanger, he realised many of the most important buildings of this era in Innsbruck.

Late in life but with a similarly practice-orientated background that was typical of 19th century master builders, Anton Fritz started his construction company in 1888. He grew up remotely in Graun in the Vinschgau Valley. After working as a foreman, plasterer and bricklayer, he decided to attend the trade school in Innsbruck at the age of 36. Talent and luck brought him his breakthrough as a planner with the country-style villa at Karmelitergasse 12. In its heyday, his construction company employed 150 people. In 1912, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War and the resulting slump in the construction industry, he handed over his company to his son Adalbert. Anton Fritz's legacy includes his own home at Müllerstraße 4, the Mader house in Glasmalereistraße and houses on Claudiaplatz and Sonnenburgplatz.

With Carl Kohnle, Carl Albert, Karl Lubomirski and Simon Tommasi, Innsbruck had other master builders who immortalised themselves in the cityscape with buildings typical of the late 19th century. They all made Innsbruck's new streets shine in the prevailing architectural zeitgeist of the last 30 years of the Danube Monarchy. Residential buildings, railway stations, official buildings and churches in the vast empire between the Ukraine and Tyrol looked similar across the board. New trends such as Art Nouveau emerged only hesitantly. In Innsbruck, it was the Munich architect Josef Bachmann who set a new accent in civic design with the redesign of the façade of the Winklerhaus. Building activity came to a halt at the beginning of the First World War. After the war, the era of neoclassical historicism and Heimatstil was finally history. Times were more austere and the requirements for residential buildings had changed. More important than a representative façade and large, stately rooms became affordable living space and modern facilities with sanitary installations during the housing shortage of the sparse, young Republic of German-Austria. The more professional training of master builders and architects at the k.k. Staatsgewerbeschule also contributed to a new understanding of the building trade than the often self-taught veterans of the gold-digger era of classicism had. Walks in Saggen and parts of Wilten and Pradl still take you back to the days of the Wilhelminian style. Claudiaplatz and Sonnenburgplatz are among the most impressive examples. The construction company Huter and Sons still exists today. The company is now located in Sieglanger in Josef-Franz-Huter-Straße, named after the company founder. Although the residential building in Kaiser-Josef-Straße no longer bears the company's logo, its opulence is still a relic of the era that changed Innsbruck's appearance forever. In addition to his home in Schöpfstraße, Wilten is home to a second building belonging to the Retter family. On the Innrain opposite the university is the Villa Retter. Josef Retter's eldest daughter Maria Josefa, who herself was educated by the reform pedagogue Maria Montessori, opened the first „House of the child“ of Innsbruck. Above the entrance is a portrait of the patron Josef Retter, while the south façade is adorned with a mosaic in the typical style of the 1930s, hinting at the building's original purpose. A smiling, blonde girl embraces her mother, who is holding a book, and her father, who is carrying a hammer. The small burial chapel at the Westfriedhof cemetery, which serves as the Retters' family burial place, is also a legacy of this important family for Innsbruck that is well worth seeing.

A republic is born

Few eras are more difficult to grasp than the interwar period. The Roaring TwentiesJazz and automobiles come to mind, as do inflation and the economic crisis. In big cities like Berlin, young ladies behaved as Flappers mit Bubikopf, Zigarette und kurzen Röcken zu den neuen Klängen lasziv, Innsbrucks Bevölkerung gehörte als Teil der jungen Republik Österreich zum größten Teil zur Fraktion Armut, Wirtschaftskrise und politischer Polarisierung. Schon die Ausrufung der Republik am Parlament in Wien vor über 100.000 mehr oder minder begeisterten, vor allem aber verunsicherten Menschen verlief mit Tumulten, Schießereien, zwei Toten und 40 Verletzten alles andere als reibungsfrei. Wie es nach dem Ende der Monarchie und dem Wegfall eines großen Teils des Staatsterritoriums weitergehen sollte, wusste niemand. Das neue Österreich erschien zu klein und nicht lebensfähig. Der Beamtenstaat des k.u.k. Reiches setzte sich nahtlos unter neuer Fahne und Namen durch. Die Bundesländer als Nachfolger der alten Kronländer erhielten in der Verfassung im Rahmen des Föderalismus viel Spielraum in Gesetzgebung und Verwaltung. Die Begeisterung für den neuen Staat hielt sich aber in der Bevölkerung in Grenzen. Nicht nur, dass die Versorgungslage nach dem Wegfall des allergrößten Teils des ehemaligen Riesenreiches der Habsburger miserabel war, die Menschen misstrauten dem Grundgedanken der Republik. Die Monarchie war nicht perfekt gewesen, mit dem Gedanken von Demokratie konnten aber nur die allerwenigsten etwas anfangen. Anstatt Untertan des Kaisers war man nun zwar Bürger, allerdings nur Bürger eines Zwergstaates mit überdimensionierter und in den Bundesländern wenig geliebter Hauptstadt anstatt eines großen Reiches. In den ehemaligen Kronländern, die zum großen Teil christlich-sozial regiert wurden, sprach man gerne vom Viennese water headwho was fed by the yields of the industrious rural population.

Other federal states also toyed with the idea of seceding from the Republic after the plan to join Germany, which was supported by all parties, was prohibited by the victorious powers of the First World War. The Tyrolean plans, however, were particularly spectacular. From a neutral Alpine state with other federal states, a free state consisting of Tyrol and Bavaria or from Kufstein to Salurn, an annexation to Switzerland and even a Catholic church state under papal leadership, there were many ideas. The most obvious solution was particularly popular. In Tyrol, feeling German was nothing new. So why not align oneself politically with the big brother in the north? This desire was particularly pronounced among urban elites and students. The annexation to Germany was approved by 98% in a vote in Tyrol, but never materialised.

Instead of becoming part of Germany, they were subject to the unloved Wallschen. Italian troops occupied Innsbruck for almost two years after the end of the war. At the peace negotiations in Paris, the Brenner Pass was declared the new border. The historic Tyrol was divided in two. The military was stationed at the Brenner Pass to secure a border that had never existed before and was perceived as unnatural and unjust. In 1924, the Innsbruck municipal council decided to name squares and streets around the main railway station after South Tyrolean towns. Bozner Platz, Brixnerstrasse and Salurnerstrasse still bear their names today. Many people on both sides of the Brenner felt betrayed. Although the war was far from won, they did not see themselves as losers to Italy. Hatred of Italians reached its peak in the interwar period, even if the occupying troops were emphatically lenient. A passage from the short story collection "The front above the peaks" by the National Socialist author Karl Springenschmid from the 1930s reflects the general mood:

"The young girl says, 'Becoming Italian would be the worst thing.

Old Tappeiner just nods and grumbles: "I know it myself and we all know it: becoming a whale would be the worst thing."

Trouble also loomed in domestic politics. The revolution in Russia and the ensuing civil war with millions of deaths, expropriation and a complete reversal of the system cast its long shadow all the way to Austria. The prospect of Soviet conditions machte den Menschen Angst. Österreich war tief gespalten. Hauptstadt und Bundesländer, Stadt und Land, Bürger, Arbeiter und Bauern – im Vakuum der ersten Nachkriegsjahre wollte jede Gruppe die Zukunft nach ihren Vorstellungen gestalten. Die Kulturkämpfe der späten Monarchie zwischen Konservativen, Liberalen und Sozialisten setzte sich nahtlos fort. Die Kluft bestand nicht nur auf politischer Ebene. Moral, Familie, Freizeitgestaltung, Erziehung, Glaube, Rechtsverständnis – jeder Lebensbereich war betroffen. Wer sollte regieren? Wie sollten Vermögen, Rechte und Pflichten verteilt werden. Ein kommunistischer Umsturz war besonders in Tirol keine reale Gefahr, ließ sich aber medial gut als Bedrohung instrumentalisieren, um die Sozialdemokratie in Verruf zu bringen. 1919 hatte sich in Innsbruck zwar ein Workers', farmers' and soldiers' council nach sowjetischem Vorbild ausgerufen, sein Einfluss blieb aber gering und wurde von keiner Partei unterstützt. Ab 1920 bildeten sich offiziell sogenannten Soldatenräte, die aber christlich-sozial dominiert waren. Das bäuerliche und bürgerliche Lager rechts der Mitte militarisierte sich mit der Tiroler Heimatwehr professioneller und konnte sich über stärkeren Zulauf freuen als linke Gruppen, auch dank kirchlicher Unterstützung. Die Sozialdemokratie wurde von den Kirchkanzeln herab und in konservativen Medien als Jewish Party and homeless traitors to their country. They were all too readily blamed for the lost war and its consequences. The Tiroler Anzeiger summarised the people's fears in a nutshell: "Woe to the Christian people if the Jews=Socialists win the elections!".

With the new municipal council regulations of 1919, which provided for universal suffrage for all adults, the Innsbruck municipal council comprised 40 members. Of the 24,644 citizens called to the ballot box, an incredible 24,060 exercised their right to vote. Three women were already represented in the first municipal council with free elections. While in the rural districts the Tyrolean People's Party as a merger of Farmers' Union, People's Association und Catholic Labour Despite the strong headwinds in Innsbruck, the Social Democrats under the leadership of Martin Rapoldi were always able to win between 30 and 50% of the vote in the first elections in 1919. The fact that the Social Democrats did not succeed in winning the mayor's seat was due to the majorities in the municipal council formed by alliances with other parties. Liberals and Tyrolean People's Party was at least as hostile to social democracy as he was to the federal capital Vienna and the Italian occupiers.

But high politics was only the framework of the actual misery. The as Spanish flu This epidemic, which has gone down in history, also took its toll in Innsbruck in the years following the war. Exact figures were not recorded, but the number of deaths worldwide is estimated at 27 - 50 million. In Innsbruck, at the height of the Spanish flu epidemic, it is estimated that around 100 people fell victim to the disease every day. Many Innsbruck residents had not returned home from the battlefields and were missing as fathers, husbands and labourers. Many of those who had made it back were wounded and scarred by the horrors of war. As late as February 1920, the „Tyrolean Committee of the Siberians" im Gasthof Breinößl "...in favour of the fund for the repatriation of our prisoners of war..." organised a charity evening. Long after the war, the province of Tyrol still needed help from abroad to feed the population. Under the heading "Significant expansion of the American children's aid programme in Tyrol" was published on 9 April 1921 in the Innsbrucker Nachrichten to read: "Taking into account the needs of the province of Tyrol, the American representatives for Austria have most generously increased the daily number of meals to 18,000 portions.“

Then there was unemployment. Civil servants and public sector employees in particular lost their jobs after the League of Nations linked its loan to severe austerity measures. Salaries in the public sector were cut. There were repeated strikes. Tourism as an economic factor was non-existent due to the problems in the neighbouring countries, which were also shaken by the war. The construction industry, which had been booming before the war, collapsed completely. Innsbruck's largest company Huter & Söhne hatte 1913 über 700 Mitarbeiter, am Höhepunkt der Wirtschaftskrise 1933 waren es nur noch 18. Der Mittelstand brach zu einem guten Teil zusammen. Der durchschnittliche Innsbrucker war mittellos und mangelernährt. Oft konnten nicht mehr als 800 Kalorien pro Tag zusammengekratzt werden. Die Kriminalitätsrate war in diesem Klima der Armut höher als je zuvor. Viele Menschen verloren ihre Bleibe. 1922 waren in Innsbruck 3000 Familien auf Wohnungssuche trotz eines städtischen Notwohnungsprogrammes, das bereits mehrere Jahre in Kraft war. In alle verfügbaren Objekte wurden Wohnungen gebaut. Am 11. Februar 1921 fand sich in einer langen Liste in den Innsbrucker Nachrichten on the individual projects that were run, including this item:

„The municipal hospital abandoned the epidemic barracks in Pradl and made them available to the municipality for the construction of emergency flats. The necessary loan of 295 K (note: crowns) was approved for the construction of 7 emergency flats.“

Very little happened in the first few years. Then politics awoke from its lethargy. The crown, a relic from the monarchy, was replaced by the schilling as Austria's official currency on 1 January 1925. The old currency had lost more than 95% of its value against the dollar between 1918 and 1922, or the pre-war exchange rate. Innsbruck, like many other Austrian municipalities, began to print its own money. The amount of money in circulation rose from 12 billion crowns to over 3 trillion crowns between 1920 and 1922. The result was an epochal inflation.

With the currency reorganisation following the League of Nations loan under Chancellor Ignaz Seipel, not only banks and citizens picked themselves up, but public building contracts also increased again. Innsbruck modernised itself. There was what economists call a false boom. This short-lived economic recovery was a Bubble, However, the city of Innsbruck was awarded major projects such as the Tivoli, the municipal indoor swimming pool, the high road to the Hungerburg, the mountain railways to the Isel and the Nordkette, new schools and apartment blocks. The town bought Lake Achensee and, as the main shareholder of TIWAG, built the power station in Jenbach. The first airport was built in Reichenau in 1925, which also involved Innsbruck in air traffic 65 years after the opening of the railway line. In 1930, the university bridge connected the hospital in Wilten and the Höttinger Au. The Pembaur Bridge and the Prince Eugene Bridge were built on the River Sill. The signature of the new, large mass parties in the design of these projects cannot be overlooked.

The first republic was a difficult birth from the remnants of the former monarchy and it was not to last long. Despite the post-war problems, however, a lot of positive things also happened in the First Republic. Subjects became citizens. What began in the time of Maria Theresa was now continued under new auspices. The change from subject to citizen was characterised not only by a new right to vote, but above all by the increased care of the state. State regulations, schools, kindergartens, labour offices, hospitals and municipal housing estates replaced the benevolence of the landlord, sovereigns, wealthy citizens, the monarchy and the church.

To this day, much of the Austrian state and Innsbruck's cityscape and infrastructure are based on what emerged after the collapse of the monarchy. In Innsbruck, there are no conscious memorials to the emergence of the First Republic in Austria. The listed residential complexes such as the Slaughterhouse blockthe Pembaurblock or the Mandelsbergerblock oder die Pembaur School are contemporary witnesses turned to stone. Every year since 1925, World Savings Day has commemorated the introduction of the schilling. Children and adults should be educated to handle money responsibly.

The Bocksiedlung and Austrofascism

In addition to hunger, political polarisation characterised people's lives in the 1920s and 1930s. Although the collapse of the monarchy had brought about a republic, the two major popular parties, the Social Democrats and the Christian Socials, were as hostile to each other as two scorpions. Both parties set up paramilitary blocs to back up their political agenda with violence on the streets if necessary. The Republican Defence League on the side of the Social Democrats and various Christian-social or even monarchist-orientated Home defenceFor the sake of simplicity, the different groups will be summarised under this collective term, were like civil war parties. Many politicians and functionaries on both sides had fought at the front during the war and were correspondingly militarised. The Tiroler Heimatwehr was able to rely on better infrastructure and a political network in rural Tyrol thanks to the support of the Catholic Church. On 12 November 1928, the tenth anniversary of the founding of the Republic, 18,000 members of the Austrian armed forces marched through the city on the First All-Austrian Homeland March to underline their superiority on the highest holiday of the domestic social democracies. The Styrian troops were quartered in Wilten Abbey, among other places.

From 1930, the NSDAP also became increasingly present in the public sphere. It was able to gain supporters, particularly among students and young, disillusioned workers. By 1932, the party already had 2,500 members in Innsbruck. There were repeated violent clashes between the opposing political groups. The so-called Höttinger Saalschlacht Hötting was not yet part of Innsbruck at that time. The community was mainly inhabited by labourers. In this red National Socialists planned a rally in the Tyrolean bastion at the Gasthof Golden Beara meeting place for the Social Democrats. This provocation ended in a fight that resulted in over 30 people being injured and one death from a stab wound on the National Socialist side. The riots spread throughout the city, with the injured even clashing in the hospital. Only with the help of the gendarmerie and the army was it possible to separate the opponents.

After years of civil war-like conditions, the Christian Socialists under Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß (1892 - 1934) prevailed in 1933 and eliminated parliament. There was no significant fighting in Innsbruck. On 15 March, the party house of the Social Democratic Labour Party Tyrol im Hotel Sonne The Republican Protection League leader Gustav Kuprian was arrested for high treason and the individual groups disarmed. Dollfuß's goal was to establish the so-called Austrian corporative statea one-party state without opposition, curtailing elementary rights such as freedom of the press and freedom of assembly. In Tyrol in 1933, the Tiroler Wochenzeitung was newly founded to function as a party organ. The entire state apparatus was to be organised along the lines of Mussolini's fascism in Italy under the Vaterländischen Front united: Anti-socialist, authoritarian, conservative in its view of society, anti-democratic, anti-Semitic and militarised. The Innsbruck municipal council was reduced from 40 to 28 members. Instead of free elections, they were appointed by the provincial governor, which meant that only conservative councillors were represented.

Dollfuß was extremely popular in Tyrol, as pictures of the packed square in front of the Hofburg during one of his speeches in 1933 show. His policies were the closest thing to the Habsburg monarchy. His political course was supported by the Catholic Church. This gave him access to infrastructure, press organs and front organisations. Against the hated socialists, the Patriotic Front with their paramilitary units. They did not shy away from repression and acts of violence against life and limb and the facilities of political opponents. Socialists, social democrats, trade unionists and communists were repeatedly arrested. In 1934, members of the Heimwehr destroyed the monument to the Social Democrat Martin Rapoldi in Kranebitten. The press was politically controlled and censored. The articles glorified the idyllic rural life. Families with many children were supported financially. The segregation of the sexes in schools and the reorganisation of the curriculum for girls, combined with pre-military training for boys, was in the interests of a large part of the population. The traditionally orientated cultural policy, with which Austria presented itself as the better Germany under the anti-clerical National Socialist leadership appealed to the conservative part of society. As early as 1931, some Tyrolean mayors had joined forces to have the entry ban for the Habsburgs lifted, so the unspoken long-term goal of reinstalling the monarchy by the Christian Socials enjoyed broad support.

On 25 July 1934, the banned National Socialists attempted a coup in Vienna, in which Dollfuß was killed. There was also an attempted coup in Innsbruck. A policeman was shot dead in Herrengasse when a group of National Socialists attempted to take control of the city. Hitler, who had not ordered the attacks, distanced himself, and the Austrian groups of the banned party were restricted as a result. In Innsbruck, the "Verfügung des Regierungskommissärs der Landeshauptstadt Tirols“ der Platz vor dem Tiroler Landestheater als Dollfußplatz led. Dollfuß had met with the Tyrolean Heimwehr leader Richard Steidle at a rally here two weeks before his death. Steidle himself had been the victim of political violence on several occasions. In 1932, he was attacked on the tram after the Höttinger Saalschlacht, and the following year he was the victim of an assassination attempt in front of his house in Leopoldstraße. After the NSDAP seized power, he was sent to Buchenhausen concentration camp, where he died in 1940.

Dollfuß' successor as Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg (1897 - 1977) was a Tyrolean by birth and a member of the Innsbruck student fraternity Austria. He ran a law firm in Innsbruck for a long time. In 1930, he founded a paramilitary unit called Ostmärkische Sturmscharenwhich formed the counterweight of the Christian Socials to the radical Heimwehr groups. After the February Uprising in 1934, as Minister of Justice in the Dollfuß cabinet, he was jointly responsible for the execution of several Social Democrats.

However, Austrofascism was unable to turn the tide in the 1930s, especially economically. The economic crisis, which also hit Austria in 1931 and fuelled the radical, populist policies of the NSDAP, hit hard. State investment in major infrastructure projects came to a standstill. The unemployment rate in 1933 was 25%. The restriction of social welfare, which was introduced at the beginning of the First Republick was introduced had dramatic effects. The long-term unemployed were excluded from receiving social benefits as "Discontinued" excluded. Poverty caused the crime rate to rise, and robberies, muggings and thefts became more frequent.

As in previous decades, the housing situation was a particular problem. Despite the city's efforts to create modern living space, many Innsbruck residents still lived in shacks. Bathrooms or one bedroom per person were the exception. Since the great growth of Innsbruck from the 1880s onwards, the housing situation was precarious for many people. The railways, industrialisation, refugees from the German-speaking regions of Italy and the economic crisis had pushed Innsbruck to the brink of the possible. After Vienna, Innsbruck had the second highest number of residents per house. Rents for housing were so high that workers often slept in stages in order to share the costs. Although new blocks of flats and homeless shelters were built, especially in Pradl, such as the workers' hostel in Amthorstraße in 1907, the hostel in Hunoldstraße and the Pembaurblock, this was not enough to deal with the situation. Out of this need and despair, several shanty towns and settlements emerged on the outskirts of the city, founded by the marginalised, the desperate and those left behind who found no place in the system. In the prisoner-of-war camp in the Höttinger Au, people took up residence in the barracks after they had been invalided out. The best known and most notorious to this day was the Bocksiedlung on the site of today's Reichenau. From 1930, several families settled in barracks and caravans between the airport, which was located there at the time, and the barracks of the Reichenau concentration camp. The legend of its origins speaks of Otto and Josefa Rauth as the founders, whose caravan was stranded here. Rauth was not only economically poor, but also morally poor as an avowed communist in Tyrolean terms. His raft, the Noah's Ark, which he wanted to use to reach the Soviet Union via the Inn and Danube, anchored in front of Gasthof Sandwirt.

Gradually, an area emerged on the edge of both the town and society, which was run by the unofficial mayor of the estate, Johann Bock (1900 - 1975), like an independent commune. He regulated the agendas in his sphere of influence in a rough and ready manner.

The Bockala had a terrible reputation among the good citizens of the city. And despite all the historical smoothing and nostalgia, probably not without good reason. As helpful and supportive as the often eccentric residents of the estate could be among themselves, physical violence and petty crime were commonplace. Excessive alcohol consumption was common practice. The streets were unpaved. There was no running water, sewage system or sanitary facilities, nor was there a regular electricity supply. Even the supply of drinking water was precarious for a long time, which brought with it the constant risk of epidemics.

Many, but not all, of the residents were unemployed or criminals. In many cases, it was people who had fallen through the system who settled in the Bocksiedlung. Having the wrong party membership could be enough to prevent you from getting a flat in Innsbruck in the 1930s. Karl Jaworak, who carried out an assassination attempt on Federal Chancellor Prelate Ignaz Seipel in 1924, lived at Reichenau 5a from 1958 after his imprisonment and deportation to a concentration camp during the Nazi regime.

The furnishings of the Bocksiedlung dwellings were just as heterogeneous as the inhabitants. There were caravans and circus wagons, wooden barracks, corrugated iron huts, brick and concrete houses. The Bocksiedlung also had no fixed boundaries. Bockala In Innsbruck, being a citizen was a social status that largely originated in the imagination of the population.

Within the settlement, the houses and carriages built were rented out and sold. With the toleration of the city of Innsbruck, inherited values were created. The residents cultivated self-sufficient gardens and kept livestock, and dogs and cats were also on the menu in meagre times.

The air raids of the Second World War exacerbated the housing situation in Innsbruck and left the Bocksiedlung grow. At its peak, there are said to have been around 50 accommodations. The barracks of the Reichenau concentration camp were also used as sleeping quarters after the last imprisoned National Socialists held there were transferred or released, although the concentration camp was not part of the Bocksiedlung in the narrower sense.

The beginning of the end was the 1964 Olympic Games and a fire in the settlement a year earlier. Malicious tongues claim that this was set to speed up the eviction. In 1967, Mayor Alois Lugger and Johann Bock negotiated the next steps and compensation from the municipality for the eviction, reportedly in an alcohol-fuelled atmosphere. In 1976, the last quarters were evacuated due to hygienic deficiencies.

Many former residents of the Bocksiedlung were relocated to municipal flats in Pradl, the Reichenau and in the O-Village quartered here. The customs of the Bocksiedlung lived on for a number of years, which accounts for the poor reputation of the urban apartment blocks in these neighbourhoods to this day.

A reappraisal of what many historians call the Austrofascism has hardly ever happened in Austria. In the church of St Jakob im Defereggen in East Tyrol or in the parish church of Fritzens, for example, pictures of Dollfuß as the protector of the Catholic Church can still be seen, more or less without comment. In many respects, the legacy of the divided situation of the interwar period extends to the present day. To this day, there are red and black motorists' clubs, sports associations, rescue organisations and alpine associations whose roots go back to this period.

The history of the Bocksiedlung was compiled in many interviews and painstaking detail work by the city archives for the book "Bocksiedlung. A piece of Innsbruck" of the city archive.

Air raids on Innsbruck

Wie der Lauf der Geschichte der Stadt unterliegt auch ihr Aussehen einem ständigen Wandel. Besonders gut sichtbare Veränderungen im Stadtbild erzeugten die Jahre rund um 1500 und zwischen 1850 bis 1900, als sich politische, wirtschaftliche und gesellschaftliche Veränderungen in besonders schnellem Tempo abspielten. Das einschneidendste Ereignis mit den größten Auswirkungen auf das Stadtbild waren aber wohl die Luftangriffe auf die Stadt im Zweiten Weltkrieg, als aus der „Heimatfront“ der Nationalsozialisten ein tatsächlicher Kriegsschauplatz wurde. Die Lage am Fuße des Brenners war über Jahrhunderte ein Segen für die Stadt gewesen, nun wurde sie zum Verhängnis. Innsbruck war ein wichtiger Versorgungsbahnhof für den Nachschub an der Italienfront. In der Nacht vom 15. auf den 16. Dezember 1943 erfolgte der erste alliierte Luftangriff auf die schlecht vorbereitete Stadt. 269 Menschen fielen den Bomben zum Opfer, 500 wurden verletzt und mehr als 1500 obdachlos. Über 300 Gebäude, vor allem in Wilten und der Innenstadt, wurden zerstört und beschädigt. Am Montag, den 18. Dezember fanden sich in den Innsbrucker Nachrichten, dem Vorgänger der Tiroler Tageszeitung, auf der Titelseite allerhand propagandistische Meldungen vom erfolgreichen und heroischen Abwehrkampf der Deutschen Wehrmacht an allen Fronten gegenüber dem Bündnis aus Anglo-Amerikanern und dem Russen, nicht aber vom Bombenangriff auf Innsbruck.

Bombenterror über Innsbruck

Innsbruck, 17. Dez. Der 16. Dezember wird in der Geschichte Innsbrucks als der Tag vermerkt bleiben, an dem der Luftterror der Anglo-Amerikaner die Gauhauptstadt mit der ganzen Schwere dieser gemeinen und brutalen Kampfweise, die man nicht mehr Kriegführung nennen kann, getroffen hat. In mehreren Wellen flogen feindliche Kampfverbände die Stadt an und richteten ihre Angriffe mit zahlreichen Spreng- und Brandbomben gegen die Wohngebiete. Schwerste Schäden an Wohngebäuden, an Krankenhäusern und anderen Gemeinschaftseinrichtungen waren das traurige, alle bisherigen Schäden übersteigende Ergebnis dieses verbrecherischen Überfalles, der über zahlreiche Familien unserer Stadt schwerste Leiden und empfindliche Belastung der Lebensführung, das bittere Los der Vernichtung liebgewordenen Besitzes, der Zerstörung von Heim und Herd und der Heimatlosigkeit gebracht hat. Grenzenloser Haß und das glühende Verlangen diese unmenschliche Untat mit schonungsloser Schärfe zu vergelten, sind die einzige Empfindung, die außer der Auseinandersetzung mit den eigenen und den Gemeinschaftssorgen alle Gemüter bewegt. Wir alle blicken voll Vertrauen auf unsere Soldaten und erwarten mit Zuversicht den Tag, an dem der Führer den Befehl geben wird, ihre geballte Kraft mit neuen Waffen gegen den Feind im Westen einzusetzen, der durch seinen Mord- und Brandterror gegen Wehrlose neuerdings bewiesen hat, daß er sich von den asiatischen Bestien im Osten durch nichts unterscheidet – es wäre denn durch größere Feigheit. Die Luftschutzeinrichtungen der Stadt haben sich ebenso bewährt, wie die Luftschutzdisziplin der Bevölkerung. Bis zur Stunde sind 26 Gefallene gemeldet, deren Zahl sich aller Voraussicht nach nicht wesentlich erhöhen dürfte. Die Hilfsmaßnahmen haben unter Führung der Partei und tatkräftigen Mitarbeit der Wehrmacht sofort und wirkungsvoll eingesetzt.

Diese durch Zensur und Gleichschaltung der Medien fantasievoll gestaltete Nachricht schaffte es gerade mal auf Seite 3. Prominenter wollte man die schlechte Vorbereitung der Stadt auf das absehbare Bombardement wohl nicht dem Volkskörper präsentieren. Ganz so groß wie 1938 nach dem Anschluss, als Hitler am 5. April von 100.000 Menschen in Innsbruck begeistert empfangen worden war, war die Begeisterung für den Nationalsozialismus nicht mehr. Zu groß waren die Schäden an der Stadt und die persönlichen, tragischen Verluste in der Bevölkerung. Dass die sterblichen Überreste der Opfer des Luftangriffes vom 15. Dezember 1943 am heutigen Landhausplatz vor dem neu errichteten Gauhaus als Symbol nationalsozialistischer Macht im Stadtbild aufgebahrt wurden, zeugt von trauriger Ironie des Schicksals.

Im Jänner 1944 begann man Luftschutzstollen und andere Schutzmaßnahmen zu errichten. Die Arbeiten wurden zu einem großen Teil von Gefangenen des Konzentrationslagers Reichenau durchgeführt. Insgesamt wurde Innsbruck zwischen 1943 und 1945 zweiundzwanzig Mal angegriffen. Dabei wurden knapp 3833, also knapp 50%, der Gebäude in der Stadt beschädigt und 504 Menschen starben. In den letzten Kriegsmonaten war an Normalität nicht mehr zu denken. Die Bevölkerung lebte in dauerhafter Angst. Die Schulen wurden bereits vormittags geschlossen. An einen geregelten Alltag war nicht mehr zu denken. Die Stadt wurde zum Glück nur Opfer gezielter Angriffe. Deutsche Städte wie Hamburg oder Dresden wurden von den Alliierten mit Feuerstürmen mit Zehntausenden Toten innerhalb weniger Stunden komplett dem Erdboden gleichgemacht. Viele Gebäude wie die Jesuitenkirche, das Stift Wilten, die Servitenkirche, der Dom, das Hallenbad in der Amraserstraße wurden getroffen. Besondere Behandlung erfuhren während der Angriffe historische Gebäude und Denkmäler. Das Goldene Dachl was protected with a special construction, as was Maximilian's sarcophagus in the Hofkirche. The figures in the Hofkirche, the Schwarzen Mannder, wurden nach Kundl gebracht. Die Madonna Lucas Cranachs aus dem Innsbrucker Dom wurde während des Krieges ins Ötztal überführt.

Der Luftschutzstollen südlich von Innsbruck an der Brennerstraße und die Kennzeichnungen von Häusern mit Luftschutzkellern mit ihren schwarzen Vierecken und den weißen Kreisen und Pfeilen kann man heute noch begutachten. Zwei der Stellungen der Flugabwehrgeschütze, mittlerweile nur noch zugewachsene Mauerreste, können am Lanser Köpfl oberhalb von Innsbruck besichtigt werden. In Pradl, wo neben Wilten die meisten Gebäude beschädigt wurden, weisen an den betroffenen Häusern Bronzetafeln mit dem Hinweis auf den Wiederaufbau auf einen Bombentreffer hin.