Hofkirche, Silberne Kapelle & Volkskunstmuseum

Universitätsstraße 2

Worth knowing

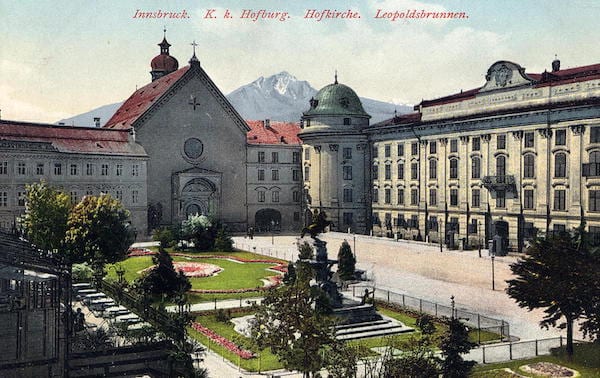

The Hofkirche in Innsbruck is one of the few churches that survived the fury of the Baroque urban renewal of the 17th and 18th centuries. The Gothic building displays the form and characteristics of the late Innsbruck Renaissance. The entrance area is modest; columns and discreet ornaments adorn the portal beneath the vaulting. The unadorned façade is almost overshadowed by the splendor of the neighboring Hofburg. Despite its seemingly modest exterior, the church is among the city’s best-known landmarks. Planned as Maximilian’s final resting place, it is the largest imperial tomb in Western Europe. In the 19th century it was regarded as the most important—by some malicious travelers even the only—sight in Innsbruck, as recorded in a travel account from 1846:

„Das meiste Kunstinteresse erregt die Hof- oder Franziskaner-, eigentlich heil. Kreuzkirche, die mehr Museum der Erzbildnerei als Kirche ist. Im Mittelschiff ist das Grabmal Kaiser Marimilian's I. angebracht, von einem unförmlichen Eisengitter umschlossen. Auf der Decke des Sargs ist der Kaiser lebensgroß, knieend, die Hände zum Gebet gefaltet, zu schauen. Diesen Erzguß verfertigte der Sicilianer Ludwig del Duca, und die an den vier Ecken der Decke angebrachten Statuetten, die Tugenden der Gerechtigkeit, Klugheit, Stärke und Mäßigkeit vorstellend… Die Seitenflächen des Sarges, in 24 Felder getheilt, enthalten auf eben so vielen Marmortafeln die merkwürdigsten Kriegs- und Friedensthaten dieses Herrschers in erhabener Arbeit.“

It is indeed true that no building reflects Maximilian I’s view of himself and his world as clearly as the Hofkirche in Innsbruck. The “last knight and first gunner” placed his public persona at the center of a long line of ancestors reaching back to the legendary British King Arthur. One could have gone even further back, as Maximilian’s court genealogist had identified the biblical patriarch Noah and the ancient Trojan hero Hector as progenitors of the Habsburgs. Larger-than-life bronze figures of these predecessors were meant to guard the Emperor’s eternal rest. Of the planned forty “Black Men” (Schwarze Mander)—not all of whom are male—only twenty-eight were ultimately realized to form a fitting honor guard. At the center of the ensemble kneels Maximilian himself. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) was involved in the design of the cenotaph enthroned at the center of the church. With his work, Dürer represented early modern capitalism in the art world. His copper engravings were already mass-produced and widely distributed in the German lands during his lifetime, making him a sought-after celebrity. Maximilian was an eager patron of the business-minded Nuremberg artist, who—like the Emperor—wanted to be visible to as broad an audience as possible through popular depictions and works. The tomb portrays the Emperor in death as he wished to be perceived in life: a symbol of a virtuous and devout existence. The oratory at the sarcophagus by Hans Waldner is an example of the highly developed woodworking craftsmanship of the Renaissance in the German-speaking world. The reliefs on the sides mark important stages in Maximilian’s life; each is a small work of art in its own right. Beginning with his marriage to Mary of Burgundy and continuing through various military episodes, the 24 panels depict the glorious deeds of the vain Habsburg. The Emperor did not live to see the completion of his tomb. In 1519, when he felt the end of his days approaching, legend has it that the Innsbruck innkeepers presented him with the debts his court had accumulated with them over the years. Enraged by this presumption, Maximilian turned his back on “his” Innsbruck and set out for his ancestral castle in Wiener Neustadt, his alternative final resting place. He died halfway there, in Linz. As egocentric as Maximilian was in life and in his self-representation, he wished to undertake his final journey in humility. He is said to have decreed that after the last rites he should no longer be addressed by his titles, that his teeth be removed, his skull shaved, and his body sewn into a shroud, so that he might appear before the Lord in heaven as a poor penitent. Faith was for him an instrument to legitimize his power, yet he was no cynic; like most of his peers on Europe’s royal thrones, he was genuinely devout. Faith as a system of order only works if one truly believes—and buildings such as the Hofkirche still demonstrate this impressively today. Because the figures intended for his substitute tomb at the fortress in Wiener Neustadt were too heavy, Maximilian’s grandson, Emperor Ferdinand I, decided decades later to have the tomb built in Innsbruck even without the mortal remains. The bronze figures had already been cast at the foundry in Mühlau. Construction on the church was completed in 1563 after ten years. Maximilian’s body was never transferred; his remains lie buried in Wiener Neustadt. His heart, as was customary for monarchs, was buried separately and rests with his first wife, Mary of Burgundy, in Bruges. Even without the body in the magnificent sarcophagus, the Schwarzmanderkirche is an impressive PR coup by the PR professional Maximilian.

What the Emperor did not achieve was accomplished by the Tyrolean resistance fighter Andreas Hofer. His mortal remains lie in an honorary grave in the Hofkirche. The path there was long, however. Hofer was executed and buried in Mantua in 1810. Thirteen years later, an unofficial delegation of Tyrolean riflemen set out to exhume his body and transfer it to Innsbruck. After initial resistance from the official state under Metternich, he was finally buried in the Hofkirche. The marble monument depicts Hofer in traditional Tyrolean dress with a flag, taking the oath of loyalty “For God, Emperor, and Fatherland,” in accordance with the ideas of the Habsburg authorities.

In addition to the bronze figures and tombs, the Schwarzmanderkirche houses a still-playable Renaissance organ. Church instruments are still used for concerts today and may seem unremarkable in the 21st century. Until the 20th century, however, attending Mass was for many people the only opportunity to experience music at all and a weekly highlight. Even today, one can experience the room-filling sound at a concert.

A noteworthy organ can also be seen in the Silver Chapel adjoining the Hofkirche. In this devotional space, Archduke Ferdinand II sought peace and seclusion—perhaps to seek absolution in dialogue with the Almighty for his wild excesses during the legendary festivities at Ambras Castle. The chapel takes its name from the lavishly decorated reliefs adorning the altar of ivory, ebony, and silver. Court architect Giovanni Lucchese and the Dutch court sculptor Alexander Colin, who had also worked on the Black Men one floor below, designed this Gothic jewel in the spirit of the Renaissance man Ferdinand, who—like Maximilian—had himself portrayed on his tomb as a worldly powerful yet devout and humble ruler. Beside him, beneath the Gothic vault, rest his first wife Philippine Welser and their children.

Those wishing to learn more about the culture and everyday life of past eras in Tyrol and the history of the Hofkirche are well served at the Folk Art Museum (Volkskunstmuseum) directly next to the church. Unlike the Ferdinandeum, this museum does not focus on high culture but on the everyday life of the broader population and folk traditions. As early as the 19th century, bourgeois-intellectual circles developed a keen interest in the distinctive character of the Tyrolean folk spirit and regional history. Legends, fairy tales, songs, customs, clothing, crafts—everything that made up the folk soul became of interest. The rise of tourism meant that everyday objects, “antiquities,” and artworks understood as patriotic cultural assets were taken home by well-to-do travelers as souvenirs and curiosities from the exotic mountain land. At the same time, industrial goods increasingly replaced products of rural craftsmanship, which for a long time had provided a source of income in agriculture, especially during winter. In 1889, the Tyrolean Trade Association, founded just under ten years earlier, decided to establish a museum dedicated to collecting arts and crafts from Tyrol in the broadest sense. With the collapse of the monarchy, this endeavor gained new significance. The founding of the Republic of German-Austria was a bumpy affair. Austria as a state had no long tradition, whereas the crown land of Tyrol could look back on a lengthy past. From the perspective of its Greater German–liberal founding fathers from the Chamber of Commerce, Tyrolean identity was to be made visible to a new public through the Folk Art Museum. Everyday Tyrolean life of past centuries became a master narrative that made the sense of belonging between the two parts of the region—separated at the Brenner Pass since 1920—tangible. In 1926, the state of Tyrol took over the extensive collection; three years later, the former Franciscan monastery was ceremoniously inaugurated as the Tyrolean Folk Art Museum by Federal President Miklas. The building, designed in the 16th century by Andrea Crivelli and Niclas Türing as a monastery and later remodeled, became, in a sense, the home of the Tyrolean folk spirit. How important interpretive authority over regional identity was for politics at the time is shown by the fact that the museum’s director, Josef Ringler, was removed from his post and replaced by a loyalist just days after Austria’s annexation to the German Reich in 1938. Today, the Folk Art Museum displays farmhouse parlors, furniture, clothing, nativity scenes, masks, and other objects representing Tyrolean traditions since the Middle Ages. The focus is not only on the culture of North Tyrol but, in the spirit of the Euroregion, also includes South Tyrol and Trentino. Particularly popular is the annual Christmas nativity exhibition, which relocates the birth of the Savior to the Holy Land of Tyrol. Debates surrounding traditional costumes, dirndls, riflemen, and customs to this day demonstrate how important national identity still is.

Maximilian I. und seine Zeit

Maximilian is one of the most important personalities in European and Innsbruck city history. He is said to have said about Tyrol: "Tirol ist ein grober Bauernkittel, der aber gut wärmt." Vielleicht war nicht nur die Lage Innsbrucks inmitten der Berge ein Grund für seine Zuneigung, Maximilian war begeisterter Jäger. Sein Vater Friedrich III. hatte 1415 in Innsbruck das Licht der Welt erblickt und die Bedeutung der Stadt hatte seither zugenommen. Maximilian übernahm 1490 die Regierungsgeschäfte Tirols auf Bitten der Landstände von seinem Vorgänger Siegmund. Der mächtige Habsburger wollte die wichtigen Assets, die das Land zu bieten hatte, nicht aus dem habsburgischen Portfolio geben. Maximilian machte die ehemalige Handelssiedlung am Inn zu einem der wichtigsten Zentren des Heiligen Römischen Reichs und veränderte damit ihre Geschicke nachhaltig. Auch die strategisch günstige Lage Innsbrucks nahe an den italienischen Kriegsschauplätzen machte die Stadt so interessant für den Kaiser. Viele Tiroler mussten auf den Schlachtfeldern den kaiserlichen Willen durchsetzen, anstatt die heimischen Felder zu bestellen. Das änderte sich erst in den letzten Regierungsjahren. Maximilian gestand 1511 den Tirolern im Tiroler Landlibell, einer Art Verfassung zu, dass sie als Soldaten nur für den Krieg zur Verteidigung des eigenen Landes herangezogen werden dürfen. Was von Maximilian-Nostalgikern, die das Dokument gerne als Freiheitsbrief ansehen, gerne vergessen wird, sind die Verpflichtungen wie die Einhebung von Sondersteuern im Kriegsfall, die damit geregelt werden. Für Innsbruck zahlte es sich auf jeden Fall aus, wenn nicht finanziell, so zumindest kulturell. „Wer immer sich im Leben kein Gedächtnis macht, der hat nach seinem Tod kein Gedächtnis und derselbe Mensch wird mit dem Glockenton vergessen.“ Maximilian actively and successfully countered this fear by erecting highly visible symbols of imperial power such as the Goldenen Dachl entgegen. Propaganda, Bild und Medien spielten eine immer stärkere Rolle, bedingt auch durch den aufkeimenden Buchdruck. Maximilian nutzte Kunst und Kultur, um sich präsent zu halten. Er hielt sich eine Reichskantorei, eine Musikkapelle, die vor allem bei öffentlichen Auftritten und Empfängen internationaler Gesandter zum Einsatz kam. Er ließ einen wahren Personenkult mit Münzen, Büchern, Druckschriften und Gemälden rund um sich selbst veranstalten.

Bei aller Romantik, die der Liebhaber höfischer Traditionen und des klassischen Rittertums pflegte, war er ein kühler Machtpolitiker. Seine Kulturpolitik und Propaganda lehnte sich vielleicht an das Mittelalter an, realpolitisch war er aber vorwärtsgewandt. Unter ihm entstanden politische Institutionen wie der Reichstag, Reichshofrat und das Reichskammergericht, die das Verhältnis von Untertanen, Landesherr und Monarchie streng regelten. Um 1500 hatte Tirol circa 300.000 Einwohner. Mehr als 80% der Menschen arbeiteten in der Landwirtschaft und lebten zum allergrößten Teil von den Erträgen der Höfe. Maximilian beschnitt in einem wahren Furor an neuen Gesetzen die bäuerlichen Rechte der Allmende. Holzschlag, Jagd und Fischerei wurden dem Landesherrn unterstellt und waren kein Allgemeingut mehr. Das hatte negative Auswirkungen auf die bäuerliche Selbstversorgung. Dank der neuen Gesetze wurden aus Jägern Wilderer. Fleisch und Fisch waren im Mittelalter für lange Zeit ein Teil des Speiseplans, nun wurde dieser Genuss zum Luxus, der oft nur illegal beschafft werden konnte. Bei einem großen Teil der Bevölkerung war Maximilian zu Lebzeiten deshalb unbeliebt.

Restrictions on self-sufficiency were joined by new taxes. It had always been customary for sovereigns to impose additional taxes on the population in the event of war. Maximilian's warfare differed from medieval conflicts. The auxiliary troops and their noble, chivalrous landlords were supplemented or completely replaced by mercenaries who knew how to use modern firearms.

Diese neue Art ins Feld zu ziehen, verschlang Unsummen. Als die Erträge aus den landesfürstlichen Besitzungen wie Münz-, Markt-, Bergwerks-, und Zollregal nicht mehr ausreichten, wurden die einzelnen Bevölkerungsgruppen je nach Stand und Vermögen besteuert, jedoch war die Steuer noch weit entfernt von unserem heutigen ausdifferenzierten System und brachten dementsprechend Ungerechtigkeit und Unmut mit sich. Ein Beispiel für eine Abgabe war Maximilians Common penny. Die Vermögenssteuer betrug zwischen 0,1 und 0,5% des Vermögens, war aber mit 1 Gulden gedeckelt. Juden mussten unabhängig von ihrem Vermögen eine Kopfsteuer von 1 Gulden bezahlen. Erstmals wurden auch Fürsten zur Kasse gebeten, bezahlten aber durch die Deckelung maximal gleich viel wie ein mittelständischer Jude. Verkündung und Exekution der Steuer unterlagen Prälaten, Pfarrern und weltlichen Herrn. Pfarrer mussten an drei Sonntagen die Steuer von der Kanzel herunter verkünden, die Beiträge gemeinsam mit Vertretern der Gerichte einsammeln und im Reichssteuerregister anlegen. Schnell begriff man, dass diese Art der Steuereinhebung nicht funktionierte. Es bedurfte eines modernen Systems und Steuermodells. Eine kollegiale Kammer, das Regiment, wachte zentral über die Länder Tirol und Vorderösterreich nach dem modernen Vorbild der Burgunder Finanzwirtschaft, die Maximilian in seiner Zeit in den Niederlanden kennengelernt hatte. Innsbruck wurde zum Finanz- und Buchhaltungszentrum für die österreichischen Länder. Die Rait chamber and the House chamber were located in the Neuhof, where today the Goldene Dachl über die Altstadt residiert. 1496 wurden die finanziellen Mittel der österreichischen Erbländer in der Schatzkammer in Innsbruck gebündelt. Vorsitzender der Hofkammer war der Brixner Bischof Melchior von Meckau, der mehr und mehr die Fugger als Kreditgeber miteinbezog. Beamten wie Jakob Villinger (1480 - 1529) wickelten in der italienisch geprägten Form der doppelten Buchhaltung den Geldverkehr mit Bankhäusern aus ganz Europa ab und probierten den kaiserlichen Finanzhaushalt in Zaum zu halten. Talentierte Kleinadelige und Bürger, studierte Juristen und ausgebildete Beamten lösten den Hochadel in bestimmender Funktion ab. Finanzexperten aus Burgund hatten die kaufmännische Leiter des Regiments über. Die Übergänge zwischen Finanz- und anderen Feldern wie Kriegsplanung und Innenpolitik waren fließend, was der neuen Beamtenschicht große Macht verlieh. War es bisher üblich, dass das Gleichgewicht zwischen Landesfürsten, Kirche, Grundherr und Untertan aus Beitrag und militärischem Schutz bestand, wurde dieses System nun durch Zwang von der Obrigkeit durchgesetzt. Maximilian argumentierte, dass es Pflicht jedes Christenmenschen, egal welchen Standes, sei, das Heilige Römische Reich gegen äußere Feinde zu verteidigen. Die Aufzeichnungen rund um die Streitereien zwischen König, Adel, Klerus, Bauern und Städten um die Abgabenleistung erinnerten schon vor Maximilian stark an heutige politische Diskussion um das Thema der Macht- und Vermögensverteilung. Der große Unterschied zwischen dem ausgehenden 15. Jahrhundert und den vorhergegangenen Jahrhunderten entstand dadurch, dass dank des modernen Beamtenapparats diese Steuern nun auch exekutiert und eingetrieben werden konnten. Der Vergleich mit der Registrierkassenpflicht, der Besteuerung von Trinkgeldern in der Gastronomie und der Diskussion um die Abschaffung des Bargeldes drängt sich auf. Das Kapital folgte der politischen Bedeutung ebenfalls nach Innsbruck. Während seiner Regentschaft beschäftigte Maximilian 350 Räte, die ihm zur Seite standen. Knapp ein Viertel dieser hochbezahlten Räte stammte aus Tirol. Gesandte und Politiker aus ganz Europa bis zum osmanischen Reich sowie Adelige ließen sich ihren Wohnsitz in Innsbruck bauen oder übernachteten in den Wirtshäusern der Stadt. Ähnlich wie Big Money aus Ölgeschäften heute Fachkräfte aller Art nach Dubai lockt, zogen das Schwazer Silber und die daran hängende Finanzwirtschaft damals Experten aller Art nach Innsbruck, einer kleinen Stadt inmitten der unwirtlichen Alpen.

During Maximilian's reign, Innsbruck underwent structural and infrastructural changes like never before. In addition to the representative Goldenen Dachl ließ er die Hofburg umgestalten, begann mit dem Bau der Hofkirche und erschuf mit dem Innsbrucker Zeughaus Europas führende Waffenschmiede. Die Straßen durch die Altstadt wurden für die feinen Leute des Hofstaats befestigt und gepflastert. Als frommer Christ im Sinne der Ritterlichkeit half der Kaiser auch den Ärmsten. 1499 ließ Maximilian die Salvatorikapelle, ein Spital für notleidende Innsbrucker, die keinen Anspruch auf einen Platz im Stadtspital hatten, renovieren und erweitern. 1509 wurde der innerstädtische Friedhof vom heutigen Domplatz hinter das Stadtspital an den heutigen Adolf-Pichler-Platz umgesiedelt. Maximilian ließ den Handelsweg im heutigen Mariahilf verlegen und verbesserte die Wasserversorgung der Stadt. Eine Feuerordnung für die Stadt Innsbruck folgte 1510. Maximilian begann auch an den Privilegien des Stiftes Wilten, dem größten Grundherrn im heutigen Stadtgebiet, zu sägen. Infrastruktur im Besitz des Klosters wie Mühle, Säge und Sillkanal sollten stärker unter landesfürstliche Kontrolle kommen.

The imperial court and the wealthy civil servants who resided in Innsbruck transformed Innsbruck's appearance and attitude. Maximilian had introduced the distinguished courtly culture of Burgundy of his first wife to Central Europe. Culturally, it was above all his second wife Bianca Maria Sforza who promoted Innsbruck. Not only did the royal wedding take place here, she also resided here for a long time, as the city was closer to her home in Milan than Maximilian's other residences. She brought her entire court with her from the Renaissance metropolis to the German lands north of the Alps. Art and entertainment in all its forms flourished.

Under Maximilian, Innsbruck not only became a cultural centre of the empire, the city also boomed economically. Among other things, Innsbruck was the centre of the postal service in the empire. Maximilian was able to build on the expertise of the gunsmiths who had already established themselves in the foundries in Hötting under his predecessor Siegmund. Platers, foundry operators, powder stampers and cutlers settled in Neustadt, St. Nikolaus, Mühlau, Hötting and along the Sill Canal. The Fugger merchant dynasty maintained an office in Innsbruck. In addition to his favoured love of Tyrolean nature, the treasures such as salt from Hall and silver from Schwaz were at least as dear and useful to him. Maximilian financed his lavish court, his election as king by the electors and the eight-year war against the Republic of Venice by mortgaging the country's mineral resources, among other things.

Maximilians Wirken in Innsbruck zu fassen, ist schwierig. Liebesbekundungen eines Kaisers schmeicheln natürlich der Volksseele bis heute. Seine materielle Hinterlassenschaft mit den vielen Prunkbauten verstärken dieses positive Image. Er machte Innsbruck zu einer kaiserlichen Residenzstadt und trieb die Modernisierung der Infrastruktur voran. Innsbruck wurde dank dem Zeughaus zum Zentrum der Rüstungsindustrie, die Schatzkammer des Reiches und wuchs wirtschaftlich und räumlich. Die Schulden, die er dafür aufnahm und das Landesvermögen, das er an die Fugger verpfändete, prägten Tirol nach seinem Tod mindestens ebenso wie die strengen Gesetze, die er der einfachen Bevölkerung verordnete. 5 Millionen Gulden soll er an Schulden hinterlassen haben, einen Betrag, den seine österreichischen Besitzungen in 20 Jahren erwirtschaften konnten. Die ausständigen Zahlungen ruinierten nach seinem Tod viele Betriebe und Dienstleute, die auf den kaiserlichen Versprechungen sitzen blieben. Frühneuzeitliche Herrscher waren nicht an die Verbindlichkeiten ihrer Vorgänger gebunden. Eine Ausnahme bildeten die Vereinbarungen mit den Fuggern, hingen daran doch Pfandrechte. In den Legenden über den Kaiser sind die harten Zeiten nicht so präsent wie das Goldene Dachl and the soft facts learnt at school. In 2019, the celebrations to mark the 500th anniversary of the death of Innsbruck's most important Habsburg under the motto "Tyrolean at heart, European in spirit". The Viennese were favourably naturalised. Salzburg has Mozart, Innsbruck Maximilian, an emperor that the Tyroleans have adapted to Innsbruck's desired identity as a rugged journeyman who prefers to be in the mountains. Today, his striking face is emblazoned on all kinds of consumer goods, from cheese to ski lifts, the emperor is the inspiration for all kinds of profane things. It is only for political agendas that he is less easy to harness than Andreas Hofer. It is probably easier for the average citizen to identify with a revolutionary landlord than with an emperor.

Philippine Welser: Klein Venedig, Kochbücher und Kräuterkunde

Philippine Welser (1527 - 1580) was the wife of Archduke Ferdinand II and one of Innsbruck's most popular rulers. The Welsers were one of the wealthiest families of their time. Their uncle Bartholomäus Welser was similarly wealthy to Jakob Fugger and also came from the class of merchants and financiers who had acquired enormous wealth around 1500. The pillars of this wealth were the spice trade with India and the mining and metal trade with the American colonies. Welser had also granted loans to the Habsburgs. Instead of paying off the loans, Emperor Charles V pledged some of the newly annexed lands in America to the Welser family, who in return received the land as a colony. Klein-VenedigVenezuela, with fortresses and settlements. They organised expeditions to discover the legendary land of gold El Dorado to discover. In order to get as much as possible out of their fiefdom, they established trading posts to participate in the profitable transatlantic slave trade between Europe, West Africa and America. Although Charles V prohibited trade with indigenous people from South Africa after 1530, the use of African slaves on the plantations and in the mines was not covered by this regulation. The brutal behaviour of the Welser led to complaints at the imperial court in 1546, where they were denied the fiefdom for Klein-Venedig was subsequently withdrawn. However, their trade relations remained intact.

Ferdinand and Philippine met at a carnival ball in Pilsen. The Habsburg fell head over heels in love with the wealthy woman from Augsburg and married her. Nobody in the House of Habsburg was particularly pleased about the couple's secret marriage, even though the business relationships between the aristocrats and the newly rich Augsburg merchants were already several decades old and the Welser's money could be put to good use. Marriages between commoners and aristocrats were considered scandalous and not befitting their status, despite their wealth. The Tyrolean prince is said to have been infatuated with his beautiful wife all his life, which is why he disregarded all conventions of the time. The emperor only recognised the marriage after the couple had asked for forgiveness for their marriage and pledged themselves to eternal secrecy. The children of the morganatic marriage were therefore excluded from the succession. Philippine was considered extremely beautiful. According to contemporary witnesses, her skin was so delicate that „man hätte einen Schluck Rotwein durch ihre Kehle fließen sehen können“. Ferdinand had Ambras Castle remodelled into its present form for his wife. His brother Maximilian even said that "Ferdinand verzaubert sai" by the beautiful Philippine Welser when Ferdinand withdrew his troops during the Turkish war to go home to his wife. The epilogue is less flattering "...I wanted the brekin to be in a sakh and what not. God forgive me."

Philippine Welser's passion was cooking. There is still a collection of recipes in the Austrian National Library today. In the Middle Ages and early modern times, the art of cookery was practised exclusively by the wealthy and aristocrats, while the vast majority of subjects had to eat whatever was available. The Middle Ages and modern times, in fact all people up until the 1950s, lived with a permanent lack of calories. Whereas today we eat too much and get ill as a result, our ancestors suffered from illnesses caused by malnutrition. Fruit was just as rare on the menu as meat. The food was monotonous and hardly flavoured. Spices such as exotic pepper were luxury goods that ordinary people could not afford. While the diet of the ordinary citizen was a dull affair, where the main aim was to get the calories for the daily work as efficiently as possible, the attitude towards food and drink began to change in Innsbruck under Ferdinand II and Philippine Welser. The court had contributed to a certain cultivation of manners and customs in Innsbruck since Frederick IV, and Philippine Welser and Ferdinand took this development to the extreme at Ambras Castle and Weiherburg Castle. The banquets they organised were legendary and often degenerated into orgies.

Herbalism was her second hobbyhorse. Philippine Welser described how to use plants and herbs to alleviate physical ailments of all kinds. "To whiten and freshen the teeth and kill the worms in them: Take rosemary wood and burn it to charcoal, crush it all to powder, bind it in a silken cloth and rub the teeth with itwas one of her tips for a healthy and cultivated existence. She had a herb garden created at Ambras Castle in Innsbruck for her hobby and her studies.

According to reports of the time, she was very popular among the Tyrolean population, as she took great care of the poor and needy. The care of the needy, led by the town council and sponsored by wealthy citizens and aristocrats, was not a speciality at the time, but common practice. Closer to salvation in the next life than through Christian charity, Caritasyou could not come.

, konnte man nicht kommen. Ihre letzte Ruhe fand Philippine Welser nach ihrem Tod 1580 in der Silbernen Kapelle in der Innsbrucker Hofkirche. Gemeinsam mit ihren als Säugling verstorbenen Kindern und Ferdinand wurde sie dort begraben. Unterhalb des Schloss Ambras erinnert die Philippine-Welser-Straße an sie.

Ferdinand II: Principe and Renaissance prince

Archduke Ferdinand II of Austria (1529 - 1595) is one of the most colourful figures in Tyrolean history. His father, Emperor Ferdinand I, gave him an excellent education. He grew up at the Spanish court of his uncle Emperor Charles V. The years in which Ferdinand received his schooling were the early years of Jesuit influence at the Habsburg courts. The young statesman was brought up entirely in the spirit of pious humanism. This was complemented by the customs of the Renaissance aristocracy. At a young age, he travelled through Italy and Burgundy and had become acquainted with a lifestyle at the wealthy courts there that had not yet established itself among the German aristocracy. Ferdinand was what today would be described as a globetrotter, a member of the educated elite or a cosmopolitan. He was considered intelligent, charming and artistic. Among his less eccentric contemporaries, Ferdinand enjoyed a reputation as an immoral and hedonistic libertine. Even during his lifetime, he was rumoured to have organised debauched and immoral orgies.

Ferdinand's father divided his kingdom between his sons. Maximilian II, who was rightly suspected of heresy and adherence to Protestant doctrines by his parents, inherited Upper and Lower Austria as well as Bohemia and Hungary. Ferdinand's younger brother Charles ruled in Inner Austria, i.e. Carinthia, Styria and Carniola. The middle child received Tyrol, which at that time extended as far as the Engadine, and the fragmented Habsburg Forelands in the west of the central European possessions. Ferdinand took over the Tyrol as sovereign in turbulent times. He had already spent several years in Innsbruck in his youth. The mines in Schwaz began to become unprofitable due to the cheap silver from America. The flood of silver from the Habsburg possessions in New Spain on the other side of the Atlantic led to inflation.

However, these financial problems did not stop Ferdinand from commissioning personal and public infrastructure. Innsbruck benefited enormously, both economically and culturally, from the fact that after years without a sovereign prince, it was now once again the centre of a ruler. Ferdinand's archducal presence attracted the aristocracy and civil servants back to Innsbruck after the decades of neglect following Maximilian's death. By the late 1560s, the administration had grown back to 1000 people, who fuelled the local economy with their money. Bakers, butchers and inns flourished again after a few barren years. At the end of the 16th century, Innsbruck had an above-average number of innkeepers compared to other towns, who earned an above-average amount of money from merchants, guests and travellers passing through. Wine houses were not only inns, but also storage and trading centres.

The Italian cities of Florence, Venice and Milan were trendsetters in terms of culture, art and architecture. Ferdinand's Tyrolean court was to be in no way inferior to them. Gone were the days when Germans were considered uncivilised in the more beautiful cities south of the Alps, barbaric or even as Pigs were labelled. To this end, he had Innsbruck remodelled in the spirit of the Renaissance. In keeping with the trend of the time, he imitated the Italian aristocratic courts. Court architect Giovanni Lucchese assisted him in this endeavour. Ferdinand spent a considerable part of his life at Ambras Castle near Innsbruck, where he amassed one of the most valuable collections of works of art and armour in the world. Ferdinand transformed the castle above the village of Amras into a modern court. His parties, masked balls and parades were legendary. During the wedding of a nephew, he had 1800 calves and 130 oxen roasted. Wine is said to have flowed from the wells instead of water for 10 days.

But Ambras Castle was not the end of Innsbruck's transformation. To the west of the city, an archway still reminds us of the Tiergartena hunting ground for Ferdinand, including a summer house also designed by Lucchese. In order for the prince to reach his weekend residence, a road was laid in the marshy Höttinger Au, which formed the basis for today's Kranebitter Allee. The Lusthaus was replaced in 1786 by what is now known as the Pulverturm The new building, which houses part of the sports science faculty of the University of Innsbruck, replaced the well-known building. The princely sport of hunting was followed in the former Lusthauswhich was the Powder Tower. In the city centre, he had the princely Comedihaus on today's Rennweg. In order to improve Innsbruck's drinking water supply, the Mühlauerbrücke bridge was built under Ferdinand to lay a water pipeline from the Mühlaubach stream into the city centre. The Jesuits, who had arrived in Innsbruck shortly before Ferdinand took office to make life difficult for troublesome reformers and church critics and to reorganise the education system, were given a new church in Silbergasse. Numerous new buildings such as the Jesuit, Franciscan, Capuchin and Servite monasteries boosted trade and the construction industry.

The new religious orders supported Ferdinand's focus on the confessional orientation of his flock. In his Tyrolean provincial ordinance issued in 1573, he not only put a stop to fornication, swearing and prostitution, but also obliged his subjects to lead a God-fearing, i.e. Catholic, lifestyle. The „Prohibition of sorcery and disbelieving warfare" prohibited any deviation from the true faith on pain of imprisonment, corporal punishment and expropriation. Jews had to wear a clearly visible ring of yellow fabric on the left side of their chest at all times. At the same time, Ferdinand brought a Jewish financier to Innsbruck to handle the money transactions for the elaborate farm management. Samuel May and his family lived in the city as princely patronage Jews. Daniel Levi delighted Ferdinand with dancing and harp playing at the theatre and Elieser Lazarus looked after his health as court physician.

Fleecing the population, living in splendour, tolerating Protestantism among his important advisors and at the same time fighting Protestantism among the people was no contradiction for the trained Renaissance prince. Already at the age of 15, he marched under his uncle Charles V in the Schmalkaldic War into battle against the enemies of the Roman Church. As a sovereign, he saw himself as Advocatus Ecclesiae (note: representative of the church) in a confessional absolutist sense, who was responsible for the salvation of his subjects. Coercive measures, the foundation of churches and monasteries such as the Franciscans and the Capuchins in Innsbruck, improved pastoral care and the staging of Jesuit theatre plays such as "The beheading of John" were the weapons of choice against Protestantism. Ferdinand's piety was not artificial, but like most of his contemporaries, he managed to adapt flexibly to the situation.

Ferdinand's politics were suitably influenced by the Italian avant-garde of the time. Machiavelli wrote his work "Il Principe", which stated that rulers were allowed to do whatever was necessary for their success, even if they were incapable of being deposed. Ferdinand II attempted to do justice to this early absolutist style of leadership and issued his Tyrolean Provincial Code A modern set of legal rules by the standards of the time. For his subjects, this meant higher taxes on their earnings as well as extensive restrictions on mountain pastures, fishing and hunting rights. The miners, mining entrepreneurs and foreign trading companies with their offices in Innsbruck also drove up food prices. It could be summarised that Ferdinand enjoyed the exclusive pleasure of hunting on his estates, while his subjects lived at subsistence level due to increasing burdens, prices and game damage.

His relationship life was eccentric for a member of the high aristocracy. Ferdinand's first "semi-wild marriage" was to the commoner Philippine Welser. After his wife #1 died, Ferdinand married the devout Anna Caterina Gonzaga, a 16-year-old Princess of Mantua, at the age of 53. However, it seems that the two did not feel much affection for each other, especially as Anna Caterina was a niece of Ferdinand. The Habsburgs were less squeamish about marriages between relatives than they were about the marriage of a nobleman to a commoner. However, he was also "only" able to father three daughters with her. Ferdinand's final resting place was in the Silver Chapel with his first wife Philippine Welser.

Andreas Hofer and the Tyrolean uprising of 1809

The Napoleonic Wars gave the province of Tyrol a national epic and, in Andreas Hofer, a hero whose splendour still shines today. However, if one subtracts the carefully constructed legend of the Tyrolean uprising against foreign rule, the period before and after 1809 was a dark chapter in Innsbruck's history, characterised by economic hardship, the devastation of war and several instances of looting. The Kingdom of Bavaria was allied with France during the Napoleonic Wars and was able to take over the province of Tyrol from the Habsburgs in several battles between 1796 and 1805. Innsbruck was no longer the capital of a crown land, but just one of many district capitals of the administrative unit Innkreis. Revenues from tolls and customs duties as well as from Hall salt left the country for the north. The British colonial blockade against Napoleon meant that Innsbruck's long-distance trade and transport industry, which had always flourished and brought prosperity, collapsed. Innsbruck's citizens had to accommodate Bavarian soldiers in their homes. The abolition of the Tyrolean provincial government, the gubernium and the Tyrolean parliament meant not only the loss of status, but also of jobs and financial resources. Inspired by the spirit of the Enlightenment, reason and the French Revolution, the new rulers set about overturning the traditional order. While the city suffered financially as a result of the war, as is always the case, the upheaval opened up new socio-political opportunities. War is the father of all things, The breath of fresh air was not inconvenient for many citizens. Modern laws such as the Alley cleaning order or compulsory smallpox immunisation were intended to promote cleanliness and health in the city. At the beginning of the 19th century, a considerable number of people were still dying from diseases caused by a lack of hygiene and contaminated drinking water. A new tax system was introduced and the powers of the nobility were further reduced. The Bavarian administration allowed associations, which had been banned in 1797, again. Liberal Innsbruckers also liked the fact that the church was pushed out of the education system. The Benedictine priest and later co-founder of the Innsbruck Music Society, Martin Goller, was appointed to Innsbruck to promote musical education.

Diese Reformen behagten einem großen Teil der Tiroler Bevölkerung nicht. Katholische Prozessionen und religiöse Feste fielen dem aufklärerischen Programm der neuen Landesherren zum Opfer. 1808 wurde vom bayerischen König für seinen gesamten Herrschaftsbereich das Gemeindeedikt eingeführt. Die Untertanen wurden darin verpflichtet öffentliche Gebäude, Brunnen, Wege, Brücken und andere Infrastruktur in Stand zu halten. Für die Tiroler Bauern, die seit Jahrhunderten von Fronarbeit größtenteils befreit waren, bedeutete das eine zusätzliche Belastung und war ein Affront gegen ihren Standesstozl. Der Funke, der das Pulverfass zur Explosion brachte, war die Aushebung junger Männer zum Dienst in der bayrisch-napoleonischen Armee, obwohl Tiroler seit dem LandlibellThe law of Emperor Maximilian stipulated that soldiers could only be called up for the defence of their own borders. On 10 April, there was a riot during a conscription in Axams near Innsbruck, which ultimately led to an uprising. For God, Emperor and Fatherland Tyrolean defence units came together to drive the small army and the Bavarian administrative officials out of Innsbruck. The riflemen were led by Andreas Hofer (1767 - 1810), an innkeeper, wine and horse trader from the South Tyrolean Passeier Valley near Meran. He was supported not only by other Tyroleans such as Father Haspinger, Peter Mayr and Josef Speckbacher, but also by the Habsburg Archduke Johann in the background.

Once in Innsbruck, the marksmen not only plundered official facilities. As with the peasants' revolt under Michael Gaismair, their heroism was fuelled not only by adrenaline but also by alcohol. The wild mob was probably more damaging to the city than the Bavarian administrators had been since 1805, and the "liberators" rioted violently, particularly against middle-class ladies and the small Jewish population of Innsbruck.

In July 1809, Bavaria and the French took control of Innsbruck following the agreement with the Habsburgs. Peace of Znojmo, which many still regard as a Viennese betrayal of the province of Tyrol. What followed was what is known as Tyrolean survey under Andreas Hofer, who had meanwhile assumed supreme command of the Tyrolean defence forces, was to go down in the history books. The Tyrolean insurgents were able to carry victory from the battlefield a total of three times. The 3rd battle in August 1809 on Mount Isel is particularly well known. "Innsbruck sees and hears what it has never heard or seen before: a battle of 40,000 combatants...“ For a short time, Andreas Hofer was Tyrol's commander-in-chief in the absence of regular facts, also for civil affairs. Innsbruck's financial plight did not change. Instead of the Bavarian and French soldiers, the townspeople now had to house and feed their compatriots from the peasant regiment and pay taxes to the new provincial government. The city's liberal and wealthy elites in particular were not happy with the new city rulers. The decrees issued by him as provincial commander were more reminiscent of a theocracy than a 19th century body of laws. Women were only allowed to go out on the streets wearing chaste veils, dance events were banned and revealing monuments such as the one on the Leopoldsbrunnen nymphs on display were banned from public spaces. Educational agendas were to return to the clergy. Liberals and intellectuals were arrested, but the Praying the rosary zum Gebot. Am Ende gab es im Herbst 1809 in der vierten und letzten Schlacht am Berg Isel eine empfindliche Niederlage gegen die französische Übermacht. Die Regierung in Wien hatte die Tiroler Aufständischen vor allem als taktischen Prellbock im Krieg gegen Napoleon benutzt. Bereits zuvor hatte der Kaiser das Land Tirol offiziell im Friedensvertrag von Schönbrunn wieder abtreten müssen. Innsbruck war zwischen 1810 und 1814 wieder unter bayrischer Verwaltung. Auch die Bevölkerung war nur noch mäßig motiviert, Krieg zu führen. Wilten wurde von den Kampfhandlungen stark in Mitleidenschaft gezogen. Das Dorf schrumpfte von über 1000 Einwohnern auf knapp 700. Hofer selbst war zu dieser Zeit bereits ein von der Belastung dem Alkohol gezeichneter Mann. Er wurde gefangengenommen und am 20. Januar 1810 in Mantua hingerichtet. Zu allem Überfluss wurde das Land geteilt. Das Etschtal und das Trentino wurden Teil des von Napoleon aus dem Boden gestampften Königreich Italien, das Pustertal wurde den französisch kontrollierten Illyrian provinces connected.

Der „Fight for freedom" symbolises the Tyrolean self-image to this day. For a long time, Andreas Hofer, the innkeeper from the South Tyrolean Passeier Valley, was regarded as an undisputed hero and the prototype of the Tyrolean who was brave, loyal to his fatherland and steadfast. The underdog who fought back against foreign superiority and unholy customs. In fact, Hofer was probably a charismatic leader, but politically untalented and conservative-clerical, simple-minded. His tactics at the 3rd Battle of Mount Isel "Do not abandon them“ (Ann.: Ihr dürft sie nur nicht heraufkommen lassen) fasst sein Wesen wohl ganz gut zusammen. In konservativen Kreisen Tirols wie den Schützen wird Hofer unkritisch und kultisch verehrt. Das Tiroler Schützenwesen ist gelebtes Brauchtum, das sich zwar modernisiert hat, in vielen dunklen Winkeln aber noch reaktionär ausgerichtet ist. Wiltener, Amraser, Pradler und Höttinger Schützen marschieren immer noch einträchtig neben Klerus, Trachtenvereinen und Marschmusikkapellen bei kirchlichen Prozessionen und schießen in die Luft, um alles Übel von Tirol und der katholischen Kirche fernzuhalten. Über die Stadt verteilt erinnern viele Denkmäler an das Jahr 1809. Die zweite Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts erfuhr eine Heroisierung der Kämpfer, die als deutsches Bollwerk gegen fremde Völkerschaften charakterisiert wurden. Der Berg Isel wurde der Stadt für die Verehrung der Freiheitskämpfer vom Stift Wilten, der katholischen Instanz Innsbrucks, zur Verfügung gestellt. Andreas Hofer und seinen Mitstreitern Josef Speckbacher, Peter Mayer, Pater Haspinger und Kajetan Sweth wurden im Stadtteil Wilten, das in der Zeit des großdeutsch-liberal dominierten Gemeinderats 1904 zu Innsbruck kam und lange unter der Verwaltung des Stiftes gestanden hatte, Straßennamen gewidmet. Das kurze Rote Gassl im alten Kern von Wilten erinnert an die Tiroler Schützen, die, in ihnen wohl fälschlich nachgesagten roten Uniformen, dem siegreichen Feldherrn Hofer nach dem Sieg in der zweiten Berg Isel Schlacht an dieser Stelle in Massen gehuldigt haben sollen. In Tirol wird Andreas Hofer bis heute gerne für alle möglichen Initiativen und Pläne vor den Karren gespannt. Vor allem im Nationalismus des 19. Jahrhunderts berief man sich immer wieder auf den verklärten Helden Andreas Hofer. Hofer wurde über Gemälde, Flugblätter und Schauspiele zur Ikone stilisiert. Aber auch heute noch kann man das Konterfei des Oberschützen sehen, wenn sich Tiroler gegen unliebsame Maßnahmen der Bundesregierung, den Transitbestimmungen der EU oder der FC Wacker gegen auswärtige Fußballvereine zur Wehr setzen. Das Motto lautet dann „Man, it's time!“. Die Legende vom wehrfähigen Tiroler Bauern, der unter Tags das Feld bestellt und sich abends am Schießstand zum Scharfschützen und Verteidiger der Heimat ausbilden lässt, wird immer wieder gerne aus der Schublade geholt zur Stärkung der „echten“ Tiroler Identität. Die Feiern zum Todestag Andreas Hofers am 20. Februar locken bis heute regelmäßig Menschenmassen aus allen Landesteilen Tirols in die Stadt. Erst in den letzten Jahrzehnten setzte eine kritische Betrachtung des erzkonservativen und mit seiner Aufgabe als Tiroler Landeskommandanten wohl überforderten Schützenhauptmanns ein, der angestachelt von Teilen der Habsburger und der katholischen Kirche nicht nur Franzosen und Bayern, sondern auch das liberale Gedankengut der Aufklärung vehement aus Tirol fernhalten wollte.

Believe, Church and Power

Die Fülle an Kirchen, Kapellen, Kruzifixen und Wandmalereien im öffentlichen Raum wirkt auf viele Besucher Innsbrucks aus anderen Ländern eigenartig. Nicht nur Gotteshäuser, auch viele Privathäuser sind mit Darstellungen der Heiligen Familie oder biblischen Szenen geschmückt. Der christliche Glaube und seine Institutionen waren in ganz Europa über Jahrhunderte alltagsbestimmend. Innsbruck als Residenzstadt der streng katholischen Habsburger und Hauptstadt des selbsternannten Heiligen Landes Tirol wurde bei der Ausstattung mit kirchlichen Bauwerkern besonders beglückt. Allein die Dimension der Kirchen umgelegt auf die Verhältnisse vergangener Zeiten sind gigantisch. Die Stadt mit ihren knapp 5000 Einwohnern besaß im 16. Jahrhundert mehrere Kirchen, die in Pracht und Größe jedes andere Gebäude überstrahlte, auch die Paläste der Aristokratie. Das Kloster Wilten war ein Riesenkomplex inmitten eines kleinen Bauerndorfes, das sich darum gruppierte. Die räumlichen Ausmaße der Gotteshäuser spiegelt die Bedeutung im politischen und sozialen Gefüge wider.

Die Kirche war für viele Innsbrucker nicht nur moralische Instanz, sondern auch weltlicher Grundherr. Der Bischof von Brixen war formal hierarchisch dem Landesfürsten gleichgestellt. Die Bauern arbeiteten auf den Landgütern des Bischofs wie sie auf den Landgütern eines weltlichen Fürsten für diesen arbeiteten. Damit hatte sie die Steuer- und Rechtshoheit über viele Menschen. Die kirchlichen Grundbesitzer galten dabei nicht als weniger streng, sondern sogar als besonders fordernd gegenüber ihren Untertanen. Gleichzeitig war es auch in Innsbruck der Klerus, der sich in großen Teilen um das Sozialwesen, Krankenpflege, Armen- und Waisenversorgung, Speisungen und Bildung sorgte. Der Einfluss der Kirche reichte in die materielle Welt ähnlich wie es heute der Staat mit Finanzamt, Polizei, Schulwesen und Arbeitsamt tut. Was uns heute Demokratie, Parlament und Marktwirtschaft sind, waren den Menschen vergangener Jahrhunderte Bibel und Pfarrer: Eine Realität, die die Ordnung aufrecht hält. Zu glauben, alle Kirchenmänner wären zynische Machtmenschen gewesen, die ihre ungebildeten Untertanen ausnützten, ist nicht richtig. Der Großteil sowohl des Klerus wie auch der Adeligen war fromm und gottergeben, wenn auch auf eine aus heutiger Sicht nur schwer verständliche Art und Weise. Verletzungen der Religion und Sitten wurden in der späten Neuzeit vor weltlichen Gerichten verhandelt und streng geahndet. Die Anklage bei Verfehlungen lautete Häresie, worunter eine Vielzahl an Vergehen zusammengefasst wurde. Sodomie, also jede sexuelle Handlung, die nicht der Fortpflanzung diente, Zauberei, Hexerei, Gotteslästerung – kurz jede Abwendung vom rechten Gottesglauben, konnte mit Verbrennung geahndet werden. Das Verbrennen sollte die Verurteilten gleichzeitig reinigen und sie samt ihrem sündigen Treiben endgültig vernichten, um das Böse aus der Gemeinschaft zu tilgen. Bis in die Angelegenheiten des täglichen Lebens regelte die Kirche lange Zeit das alltägliche Sozialgefüge der Menschen. Kirchenglocken bestimmten den Zeitplan der Menschen. Ihr Klang rief zur Arbeit, zum Gottesdienst oder informierte als Totengeläut über das Dahinscheiden eines Mitglieds der Gemeinde. Menschen konnten einzelne Glockenklänge und ihre Bedeutung voneinander unterscheiden. Sonn- und Feiertage strukturierten die Zeit. Fastentage regelten den Speiseplan. Familienleben, Sexualität und individuelles Verhalten hatten sich an den von der Kirche vorgegebenen Moral zu orientieren. Das Seelenheil im nächsten Leben war für viele Menschen wichtiger als das Lebensglück auf Erden, war dies doch ohnehin vom determinierten Zeitgeschehen und göttlichen Willen vorherbestimmt. Fegefeuer, letztes Gericht und Höllenqualen waren Realität und verschreckten und disziplinierten auch Erwachsene.

Während das Innsbrucker Bürgertum von den Ideen der Aufklärung nach den Napoleonischen Kriegen zumindest sanft wachgeküsst wurde, blieb der Großteil der Menschen weiterhin der Mischung aus konservativem Katholizismus und abergläubischer Volksfrömmigkeit verbunden. Religiosität war nicht unbedingt eine Frage von Herkunft und Stand, wie die gesellschaftlichen, medialen und politischen Auseinandersetzungen entlang der Bruchlinie zwischen Liberalen und Konservativ immer wieder aufzeigten. Seit der Dezemberverfassung von 1867 war die freie Religionsausübung zwar gesetzlich verankert, Staat und Religion blieben aber eng verknüpft. Die Wahrmund-Affäre, die sich im frühen 20. Jahrhundert ausgehend von der Universität Innsbruck über die gesamte K.u.K. Monarchie ausbreitete, war nur eines von vielen Beispielen für den Einfluss, den die Kirche bis in die 1970er Jahre hin ausübte. Kurz vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg nahm diese politische Krise, die die gesamte Monarchie erfassen sollte in Innsbruck ihren Anfang. Ludwig Wahrmund (1861 – 1932) war Ordinarius für Kirchenrecht an der Juridischen Fakultät der Universität Innsbruck. Wahrmund, vom Tiroler Landeshauptmann eigentlich dafür ausgewählt, um den Katholizismus an der als zu liberal eingestuften Innsbrucker Universität zu stärken, war Anhänger einer aufgeklärten Theologie. Im Gegensatz zu den konservativen Vertretern in Klerus und Politik sahen Reformkatholiken den Papst nur als spirituelles Oberhaupt, nicht aber als weltlich Instanz, an. Studenten sollten nach Wahrmunds Auffassung die Lücke und die Gegensätze zwischen Kirche und moderner Welt verringern, anstatt sie einzuzementieren. Seit 1848 hatten sich die Gräben zwischen liberal-nationalen, sozialistischen, konservativen und reformorientiert-katholischen Interessensgruppen und Parteien vertieft. Eine der heftigsten Bruchlinien verlief durch das Bildungs- und Hochschulwesen entlang der Frage, wie sich das übernatürliche Gebaren und die Ansichten der Kirche, die noch immer maßgeblich die Universitäten besetzten, mit der modernen Wissenschaft vereinbaren ließen. Liberale und katholische Studenten verachteten sich gegenseitig und krachten immer aneinander. Bis 1906 war Wahrmund Teil der Leo-Gesellschaft, die die Förderung der Wissenschaft auf katholischer Basis zum Ziel hatte, bevor er zum Obmann der Innsbrucker Ortsgruppe des Vereins Freie Schule wurde, der für eine komplette Entklerikalisierung des gesamten Bildungswesens eintrat. Vom Reformkatholiken wurde er zu einem Verfechter der kompletten Trennung von Kirche und Staat. Seine Vorlesungen erregten immer wieder die Aufmerksamkeit der Obrigkeit. Angeheizt von den Medien fand der Kulturkampf zwischen liberalen Deutschnationalisten, Konservativen, Christlichsozialen und Sozialdemokraten in der Person Ludwig Wahrmunds eine ideale Projektionsfläche. Was folgte waren Ausschreitungen, Streiks, Schlägereien zwischen Studentenverbindungen verschiedener Couleur und Ausrichtung und gegenseitige Diffamierungen unter Politikern. Die Los-von-Rom Bewegung des Deutschradikalen Georg Ritter von Schönerer (1842 – 1921) krachte auf der Bühne der Universität Innsbruck auf den politischen Katholizismus der Christlichsozialen. Die deutschnationalen Akademiker erhielten Unterstützung von den ebenfalls antiklerikalen Sozialdemokraten sowie von Bürgermeister Greil, auf konservativer Seite sprang die Tiroler Landesregierung ein. Die Wahrmund Affäre schaffte es als Kulturkampfdebatte bis in den Reichsrat. Für Christlichsoziale war es ein „Kampf des freissinnigen Judentums gegen das Christentum“ in dem sich „Zionisten, deutsche Kulturkämpfer, tschechische und ruthenische Radikale“ in einer „internationalen Koalition“ als „freisinniger Ring des jüdischen Radikalismus und des radikalen Slawentums“ präsentierten. Wahrmund hingegen bezeichnete in der allgemein aufgeheizten Stimmung katholische Studenten als „Verräter und Parasiten“. Als Wahrmund 1908 eine seiner Reden, in der er Gott, die christliche Moral und die katholische Heiligenverehrung anzweifelte, in Druck bringen ließ, erhielt er eine Anzeige wegen Gotteslästerung. Nach weiteren teils gewalttätigen Versammlungen sowohl auf konservativer und antiklerikaler Seite, studentischen Ausschreitungen und Streiks musste kurzzeitig sogar der Unibetrieb eingestellt werden. Wahrmund wurde zuerst beurlaubt, später an die deutsche Universität Prag versetzt.

Auch in der Ersten Republik war die Verbindung zwischen Kirche und Staat stark. Der christlichsoziale, als Eiserner Prälat in die Geschichte eingegangen Ignaz Seipel schaffte es in den 1920er Jahren bis ins höchste Amt des Staates. Bundeskanzler Engelbert Dollfuß sah seinen Ständestaat als Konstrukt auf katholischer Basis als Bollwerk gegen den Sozialismus. Auch nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg waren Kirche und Politik in Person von Bischof Rusch und Kanzler Wallnöfer ein Gespann. Erst dann begann eine ernsthafte Trennung. Glaube und Kirche haben noch immer ihren fixen Platz im Alltag der Innsbrucker, wenn auch oft unbemerkt. Die Kirchenaustritte der letzten Jahrzehnte haben der offiziellen Mitgliederzahl zwar eine Delle versetzt und Freizeitevents werden besser besucht als Sonntagsmessen. Die römisch-katholische Kirche besitzt aber noch immer viel Grund in und rund um Innsbruck, auch außerhalb der Mauern der jeweiligen Klöster und Ausbildungsstätten. Etliche Schulen in und rund um Innsbruck stehen ebenfalls unter dem Einfluss konservativer Kräfte und der Kirche. Und wer immer einen freien Feiertag genießt, ein Osterei ans andere peckt oder eine Kerze am Christbaum anzündet, muss nicht Christ sein, um als Tradition getarnt im Namen Jesu zu handeln.

Maria Theresia, Reformatorin und Landesmutter

Maria Theresia zählt zu den bedeutendsten Figuren der österreichischen Geschichte. Obwohl sie oft als Kaiserin tituliert wird, war sie offiziell "nur" unter anderem Erzherzogin von Österreich, Königin von Ungarn und Königin von Böhmen. Bedeutend waren ihre innenpolitischen Reformen. Viele davon betrafen konkret auch den Alltag der Innsbrucker in merklichem Ausmaß. Gemeinsam mit ihren Beratern Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz, Joseph von Sonnenfels und Wenzel Anton Kaunitz schaffte sie es aus den sogenannten Österreichischen Erblanden einen modernen Staat zu basteln. Anstatt der Verwaltung ihrer Territorien durch den ansässigen Adel setzte sie auf eine moderne Verwaltung. Ihre Berater hatten ganz im Stil der Aufklärung erkannt, dass sich das Staatswohl aus der Gesundheit und Bildungsgrad seiner Einzelteile ergab. Eine frühe Krankenreform Maria Theresias aus dem Jahr 1742 verpflichtete die Professoren des Fachbereichs Medizin an der Universität Innsbruck auch den Betrieb des Stadtspitals in der Neustadt sicherzustellen. Eine Schulreform veränderte die Bildungslandschaft innerhalb der Stadtmauern nicht nur thematisch, sondern auch örtlich. Untertanen sollten katholisch sein, ihre Treue aber sollte dem Staat gelten. Schulbildung wurde unter zentrale staatliche Verwaltung gestellt. Es sollten keine kritischen, humanistischen Geistesgrößen, sondern Material für den staatlichen Verwaltungsapparat erzogen werden. Über Militär und Verwaltung konnten nun auch Nichtadlige in höhere staatliche Positionen aufsteigen. Gleichzeitig sollten Reformen im Staatsdienst und in der Wirtschaft nicht nur mehr Möglichkeiten für die Untertanen schaffen, sondern auch die Staatseinnahmen erhöhen. Gewichte und Maßeinheiten wurden nominiert, um das Steuersystem undurchlässiger zu machen. Für Bürger und Bauern hatte die Vereinheitlichung der Gesetze den Vorteil, dass das Leben weniger von Grundherren und deren Launen abhing. Auch der Robot, den Bauern auf den Gütern des Grundherrn kostenfrei zu leisten hatten, wurde unter Maria Theresia abgeschafft. In Strafverfolgung und Justiz fand ein Umdenken statt. 1747 wurde in Innsbruck eine kleine Polizei which was responsible for matters relating to market supervision, trade regulations, tourist control and public decency. The penal code Constitutio Criminalis Theresiana did not abolish torture, but it did regulate its use.

As much as Maria Theresa staged herself as a pious mother of the country and is known today as an Enlightenment figure, the strict Catholic ruler was not squeamish when it came to questions of power and religion. In keeping with the trend of the Enlightenment, she had superstitions such as vampirism, which was widespread in the eastern parts of her empire, critically analysed and initiated the final end to witch trials. At the same time, however, she mercilessly expelled Protestants from the country. Many Tyroleans were forced to leave their homeland and settle in parts of the Habsburg Empire further away from the centre.

In crown lands such as Tyrol, Maria Theresa's reforms met with little favour. With the exception of a few liberals, they saw themselves more as an independent and autonomous province and less as part of a modern territorial state. The clergy also did not like the new, subordinate role, which became even more pronounced under Joseph II. For the local nobility, the reforms not only meant a loss of importance and autonomy, but also higher taxes and duties. Taxes, levies and customs duties, which had always provided the city of Innsbruck with reliable income, were now collected centrally and only partially refunded via financial equalisation. In order to minimise the fall of sons from impoverished aristocratic families and train them for civil service, Maria Theresa founded the Theresianum, das ab 1775 auch in Innsbruck eine Niederlassung hatte. Wie so oft bügelte die Zeit manche Falte aus und Innsbrucker sind mittlerweile stolz darauf, eine der bedeutendsten Herrscherpersönlichkeiten der österreichischen Geschichte beherbergt zu haben. Heute erinnern die Triumphpfote und die Hofburg in Innsbruck an die Theresianische Zeit.

Innsbruck and the House of Habsburg

Today, Innsbruck's city centre is characterised by buildings and monuments that commemorate the Habsburg family. For many centuries, the Habsburgs were a European ruling dynasty whose sphere of influence included a wide variety of territories. At the zenith of their power, they were the rulers of a "Reich, in dem die Sonne nie untergeht". Through wars and skilful marriage and power politics, they sat at the levers of power between South America and the Ukraine in various eras. Innsbruck was repeatedly the centre of power for this dynasty. The relationship was particularly intense between the 15th and 17th centuries. Due to its strategically favourable location between the Italian cities and German centres such as Augsburg and Regensburg, Innsbruck was given a special place in the empire at the latest after its elevation to a royal seat under Emperor Maximilian.

Tyrol was a province and, as a conservative region, usually favoured the dynasty. Even after its time as a royal seat, the birth of new children of the ruling family was celebrated with parades and processions, deaths were mourned in memorial masses and archdukes, kings and emperors were immortalised in public spaces with statues and pictures. The Habsburgs also valued the loyalty of their Alpine subjects to the Nibelung. In the 19th century, the Jesuit Hartmann Grisar wrote the following about the celebrations to mark the birth of Archduke Leopold in 1716:

„But what an imposing sight it was when, as night fell, the Abbot of Wilten held the final religious function in front of St Anne's Column, which had been consecrated by the blood of the country, surrounded by rows of students and the packed crowd; when, by the light of thousands of burning lights and torches, the whole town, together with the studying youth, the hope of the country, implored heaven for a blessing for the Emperor's newborn first son.“

Its inaccessible location made it the perfect refuge in troubled and crisis-ridden times. Charles V (1500 - 1558) fled during a conflict with the Protestant Schmalkaldischen Bund to Innsbruck for some time. Ferdinand I (1793 - 1875) allowed his family to stay in Innsbruck, far away from the Ottoman threat in eastern Austria. Shortly before his coronation in the turbulent summer of the 1848 revolution, Franz Josef I enjoyed the seclusion of Innsbruck together with his brother Maximilian, who was later shot by insurgent nationalists as Emperor of Mexico. A plaque at the Alpengasthof Heiligwasser above Igls reminds us that the monarch spent the night here as part of his ascent of the Patscherkofel. Some of the Tyrolean sovereigns from the House of Habsburg had no special relationship with Tyrol, nor did they have any particular affection for this German land. Ferdinand I (1503 - 1564) was educated at the Spanish court. Maximilian's grandson Charles V had grown up in Burgundy. When he set foot on Spanish soil for the first time at the age of 17 to take over his mother Joan's inheritance of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, he did not speak a word of Spanish. When he was elected German Emperor in 1519, he did not speak a word of German.

Not all Habsburgs were happy to be „allowed“ to be in Innsbruck. Married princes and princesses such as Maximilian's second wife Bianca Maria Sforza or Ferdinand II's second wife Anna Caterina Gonzaga were stranded in the harsh, German-speaking mountains after the wedding without being asked. If you also imagine what a move and marriage from Italy to Tyrol to a foreign man meant for a teenager, you can imagine how difficult life was for the princesses. Until the 20th century, children of the aristocracy were primarily brought up to be politically married. There was no opposition to this. One might imagine courtly life to be ostentatious, but privacy was not provided for in all this luxury.

Innsbruck experienced its Habsburg heyday when the city was the main residence of the Tyrolean sovereigns. Ferdinand II, Maximilian III and Leopold V and their wives left their mark on the city during their reigns. When Sigismund Franz von Habsburg (1630 - 1665) died childless as the last sovereign prince, the title of residence city was also history and Tyrol was ruled by a governor. Tyrolean mining had lost its importance and did not require any special attention. Shortly afterwards, the Habsburgs lost their possessions in Western Europe along with Spain and Burgundy, which moved Innsbruck from the centre to the periphery of the empire. In the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy of the 19th century, Innsbruck was the western outpost of a huge empire that stretched as far as today's Ukraine. Franz Josef I (1830 - 1916) ruled over a multi-ethnic empire between 1848 and 1916. However, his neo-absolutist concept of rule was out of date. Although Austria had had a parliament and a constitution since 1867, the emperor regarded this government as "his". Ministers were responsible to the emperor, who was above the government. In the second half of the 19th century, the ailing empire collapsed. On 28 October 1918, the Republic of Czechoslovakia was proclaimed, and on 29 October, Croats, Slovenes and Serbs left the monarchy. The last Emperor Charles abdicated on 11 November. On 12 November, "Deutschösterreich zur demokratischen Republik, in der alle Gewalt vom Volke ausgeht“. The chapter of the Habsburgs was over.

Despite all the national, economic and democratic problems that existed in the multi-ethnic states that were subject to the Habsburgs in various compositions and forms, the subsequent nation states were sometimes much less successful in reconciling the interests of minorities and cultural differences within their territories. Since the eastward enlargement of the EU, the Habsburg monarchy has been seen by some well-meaning historians as a pre-modern predecessor of the European Union. Together with the Catholic Church, the Habsburgs shaped the public sphere through architecture, art and culture. Goldenes DachlThe Hofburg, the Triumphal Gate, Ambras Castle, the Leopold Fountain and many other buildings still remind us of the presence of the most important ruling dynasty in European history in Innsbruck.