Viaduct arches / Mile of arches

Ing.-Etzel-Straße

Worth knowing

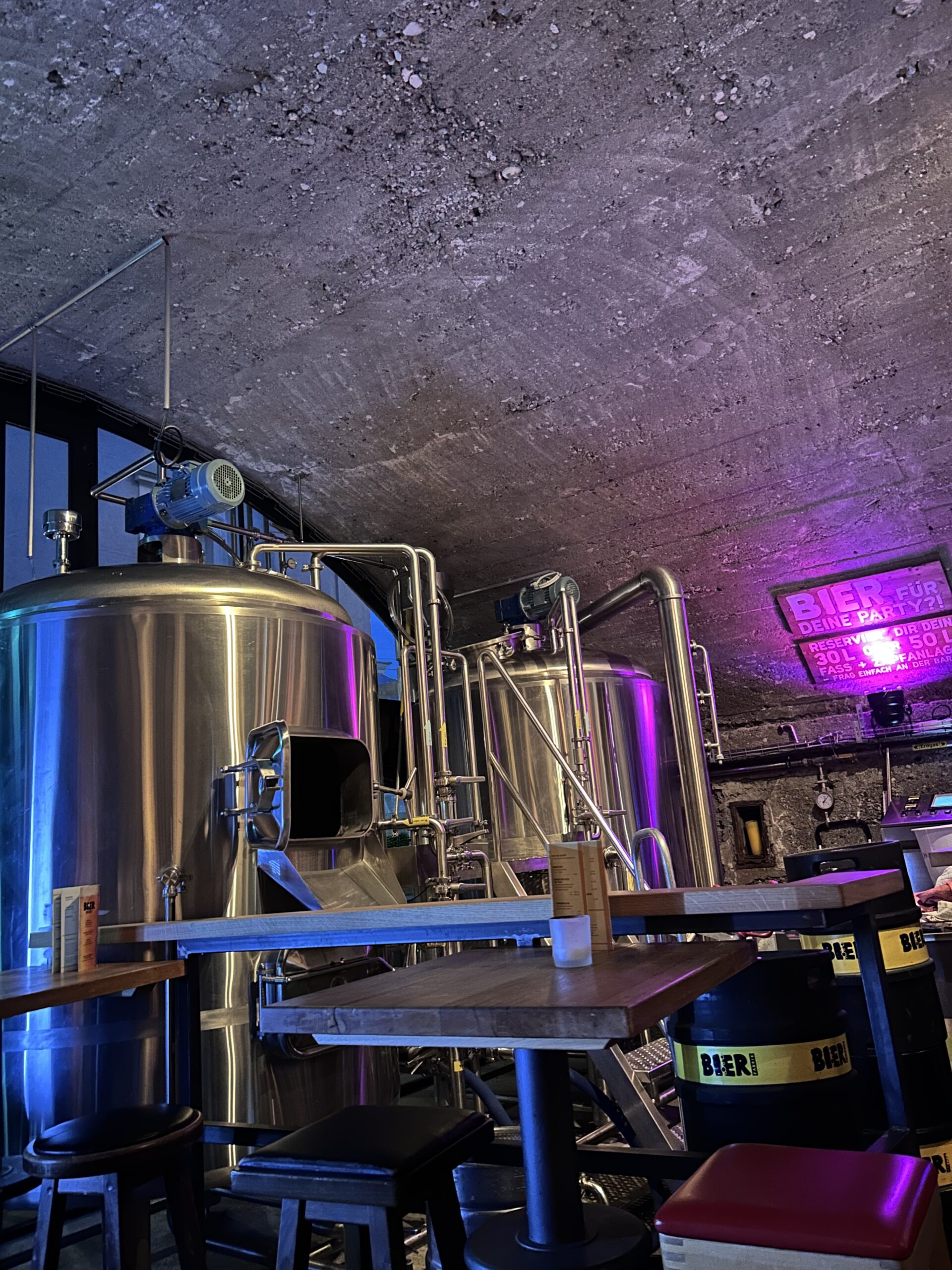

If one is to believe certain particularly cautious Innsbruck residents, the gateway to hell lies somewhere between the city center, Pradl, and Saggen. Others, however, associate the Bogenmeile with some of the best memories of their youth. For decades, the nightlife district along the railway viaduct has divided opinions and continues to inspire personal anecdotes, debates, and urban legends. Since the major renovation of the 1950s, the arches have been home to workshops, shops, and above all, bars and venues of every kind. In 1985, the youth center Z6 moved to the rear side of the arches. That same year, Bogen 13 opened, luring an alternative Innsbruck crowd away from the city center and under the viaduct for the first time. Today, pubs, bars, clubs, breweries, restaurants, and snack stands attract a colorful audience that usually celebrates peacefully until the early morning hours. In recent years, many façades have been decorated with striking street art. The district’s bad reputation stems from the comparatively rare exceptions to this peacefulness—but even more from the universal tradition of older generations finding youthful exuberance inherently threatening.

The arches form the largest structure in the city. Stretching 1.8 kilometers along Ing.-Etzel-Straße from the train station to the Mühlau railway bridge, they carry trains across the Inn toward the east. The massive structure was built between 1855 and 1858, during the construction of North Tyrol’s first railway line. The material used was Höttinger breccia, the same stone used in countless Innsbruck landmarks—from the Old Town to the Triumphal Arch to the South Tyrolean housing estates of the 1930s—until the quarries on the Hungerburg eventually closed. Thousands of workers toiled on the enormous construction site. Unlike today, the area traversed by the stone belt was not densely populated; the great wave of development in eastern Saggen—with housing blocks, the military barracks, the fairgrounds with its cycling track, and the slaughterhouse—was still far in the future.

The viaduct arches acted like an artificial barrier between Pradl and the city center. That this separation did not last is due to the mastermind behind Austrian railway construction: Carl Ritter von Ghega (1802–1860). Thanks to the turbulence of global politics, he became involved in what was perhaps the largest infrastructure project of the monarchy—possibly even in Austrian history. Born as Carlo Ghega, the son of a naval officer in Venetia, he grew up under Napoleonic rule. Only after the Congress of Vienna in 1815 did the region, as Lombardy-Venetia, come under the control of the imperial-royal monarchy. After a brief military career, he chose to study in Padua. At only 17, he completed his studies in mathematics and engineering. Following work experience in road construction and on the Northern Railway between Vienna and Moravia, he traveled to England and North America in the mid‑1830s to study railway technology in its birthplace and in the American frontier firsthand. In 1848, Ghega became Inspector General of the State Railways in the Ministry of Public Works, and in the following year head of the railway construction department and of the general directorate for state railway construction. Elevated to nobility by Emperor Franz Joseph I, the Albanian‑Italian Carlo became Carl Ritter von Ghega—the portrait of whom appeared on the Austrian 20‑schilling banknote from 1968 to 1989. It was his plans that connected the vast Habsburg Empire, from Lviv to Bregenz and Trieste. Innsbruck owes part of its ability to grow spatially to his genius. Von Ghega rejected an earlier plan by Alois von Negrelli, which envisioned an embankment between Innsbruck and Pradl. Although cheaper and faster to build, it would have permanently blocked any eastward connection for the city. In 1958, the extension of Museumstraße through the breakthrough to Rapoldipark created today’s main traffic axis between Pradl and the city center. Since then, the arches have been repeatedly renovated and adapted to evolving traffic needs. Several passageways through the viaduct’s 175 arches now connect Dreiheiligen and the various parts of Saggen. Some of the underpasses have been extensively modernized with artistic lighting installations. At Claudiaplatz, a new regional train station and a traffic‑calmed urban park have emerged. That Carl Ritter von Ghega, with his forward‑thinking engineering, would not only enable a transportation solution but inadvertently create an urban nightlife hotspot was surely never his intention.

Die Eisenbahn als Entwicklungshelfer Innsbrucks

In 1830, the world's first railway line was opened between Liverpool and Manchester. Just a few decades later, the Tyrol, which had been somewhat remote from the main trade routes and economically underdeveloped for some time, was also connected to the world with spectacular railway constructions across the Alps. While travelling had previously been expensive, long and arduous journeys in carriages, on horseback or on foot, the ever-expanding railway network meant unprecedented comfort and speed.

It was Innsbruck's mayor Joseph Valentin Maurer (1797 - 1843) who recognised the importance of the railway as an opportunity for the Alpine region. In 1836, he advocated the construction of a railway line in order to make the beautiful but hard-to-reach region accessible to the widest possible, wealthy public. The first practical pioneer of railway transport in Tyrol was Alois von Negrelli (1799 - 1858), who also played a key role in the Suez Canal project of the century. At the end of the 1830s, when the first railway lines of the Danube Monarchy went into operation in the east of the empire, he drew up a "Expert opinion on the railway from Innsbruck via Kufstein to the royal Bavarian border at the Otto Chapel near Kiefersfelden“ vorgelegt. Negrelli hatte in jungen Jahren in der k.k. Baudirektion Innsbruck service, so he knew the city very well. His report already contained sketches and a list of costs. He had suggested the Triumphpforte and the Hofgarten as a site for the main railway station. In a letter, he commented on the railway line through his former home town with these words:

"...I also hear with the deepest sympathy that the railway from Innsbruck to Kufstein is being taken seriously, as the Laage is very suitable for this and the area along the Inn is so rich in natural products and so populated that I cannot doubt its success, nor will I fail to take an active part in it myself and through my business friends when it comes to the purchase of shares. You have no idea of the new life that such an endeavour will awaken in the other side..."

Friedrich List, known as the father of the German railway, put forward the plan for a rail link from the Hanseatic cities of northern Germany via Tyrol to the Italian Adriatic. On the Austrian side, Carl Ritter von Ghega (1802 - 1860) inherited overall responsibility for the railway project within the giant Habsburg empire from Negrelli, who died young. In 1851, Austria and Bavaria signed an agreement to build a railway line to the Tyrolean capital. Construction began in May 1855. It was the largest construction site Innsbruck had ever seen. Not only was the railway station built, but the railway viaducts out of the city to the north-east also had to be constructed.

On 24 November 1858, the railway line between Innsbruck and Kufstein and on to Munich via Rosenheim went into operation. The line was ahead of its time. Unlike the rest of the railway, which was not privatised until 1860, the line opened as a private railway, operated by the previously founded Imperial and Royal Privileged Southern State, Lombard, Venetian and Central Italian Railway Company. This move meant that the costly railway construction could be excluded from Austria's already tight state budget. The first step was taken with this opening towards the eastern parts of the monarchy, especially to Munich. Goods and travellers could now be transported quickly and conveniently from Bavaria to the Alps and back. In South Tyrol, the first trains rolled over the tracks between Verona and Trento in the spring of 1859.

However, the north-south corridor was still unfinished. The first serious considerations regarding the Brenner railway were made in 1847. In 1854, the disputes south of the Brenner Pass and the commercial necessity of connecting the two parts of the country prompted the Permanent Central Fortification Commission on the plan. The loss of Lombardy after the war with France and Sardinia-Piedmont in 1859 delayed the project in northern Italy, which had become politically unstable. From the Imperial and Royal Privileged Southern State, Lombard, Venetian and Central Italian Railway Company 1860 had to Imperial and Royal Privileged Southern Railway Company to start with the detailed planning. In the following year, the mastermind behind this outstanding infrastructural achievement of the time, engineer Carl von Etzel (1812 - 1865), began to survey the site and draw up concrete plans for the layout of the railway. The planner was instructed by the private company's investors to be as economical as possible and to manage without large viaducts and bridges. Contrary to earlier considerations by Carl Ritter von Ghega to cushion the gradient up to the pass at 1370 metres above sea level by starting the line in Hall, Etzel drew up the plan, which included Innsbruck, together with his construction manager Achilles Thommen and chose the Sill Gorge as the best route. This not only saved seven kilometres of track and a lot of money, but also secured Innsbruck's important status as a transport hub. The alpine terrain, mudslides, snowstorms and floods were major challenges during construction. River courses had to be relocated, rocks blasted, earthworks dug and walls built to cope with the alpine route. The worst problems, however, were caused by the war that broke out in Italy in 1866. Patriotic German-speaking workers in particular refused to work with the "enemy". 14,000 Italian-speaking workers had to be dismissed before work could continue. Despite this, the W's highest regular railway line with its 22 tunnels blasted out of the rock was completed in a remarkably short construction time. It is not known how many men lost their lives working on the Brenner railway.

The opening was remarkably unspectacular. Many people were not sure whether they liked the technical innovation or not. Economic sectors such as lorry transport and the post stations along the Brenner line were doomed, as the death of the rafting industry after the opening of the railway line to the lowlands had shown. Even during the construction work, there were protests from farmers who feared for their profits due to the threat of importing agricultural goods. Just as the construction of the railway line had previously been influenced by world politics, a celebration was held. Austria was in national mourning due to the execution of the former Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, the brother of Franz Josef I, before a revolutionary court martial. A grand state ceremony worthy of the project was dispensed with. Instead of a priestly consecration and festive baptism, the Southern railway company 6000 guilders to the poor relief fund. Also in the Innsbrucker Nachrichten there is not a word about the revolution in transport, apart from the announcement of the last express train over the Brenner Pass and the publication of the timetable for the Southern Railway.

(The last express coach). Yesterday evening at half past seven the last express coach to South Tyrol departed from here. The oldest postilion in Innsbruck was driving the horses, his hat was fluttered with mourning, and the carriage was decorated with branches of weeping willows for the last journey. Two marksmen travelling to Matrei were the only passengers to pay their last respects to the express coach. In the last days of 1797, the beautiful, otherwise so lively and now deserted road was conspicuously dead.

Until the opening of the railway line over the Brenner Pass on 24 August 1867, Innsbruck was a terminus station of regional importance. The new, spectacular Brenner railway across the Alps connected the northern and southern parts of the country as well as Germany and Italy. The new Brenner road had already opened the year before. The Alps had lost their divisive character and their terror for transit, at least a little. While an estimated 20,000 people crossed the Brenner in 1865, three years later in the first full year of operation of the railway line there were around ten times as many. In addition, a whole flood of goods found their way across the new north-south axis, boosting trade and consumption.

Das zweite Hindernis, das zur Landeseinheit überwunden werden musste, war der Arlberg. Erste Pläne einer Bahnlinie, die die Region um den Bodensee mit dem Rest der Donaumonarchie verbinden würde, gab es bereits 1847, immer wieder wurde das Projekt aber zurückgestellt. 1871 kam es wegen durch Exportverbote von Lebensmitteln auf Grund des deutsch-französischen Krieges zu einer Hungersnot in Vorarlberg, weil Nahrungsmittel nicht schnell genug vom Osten des Riesenreiches in den äußersten Westen geliefert werden konnten. Die Wirtschaftskrise von 1873 verzögerte den Bau trotzdem erneut. Erst sieben Jahre später fiel der Beschluss im Parlament, die Bahnlinie zu realisieren. Im selben Jahr begannen östlich und westlich des Arlbergmassivs die komplizierten Bauarbeiten. 38 Wildbäche und 54 Lawinengefahrstellen mussten mit 3100 Bauwerken bei prekären Wetterverhältnissen im alpinen Gelände verbaut werden. Die bemerkenswerteste Leistung war der zehn Kilometer lange Tunnel, der zwei Gleise führt. Am 30. Juni 1883 fuhr der letzte Transport der Post mit dem Pferdewagen in feierlichem Trauerflor von Innsbruck nach Landeck. Tags darauf erledigte die Eisenbahn diesen Dienst. Mit der Eröffnung der Eisenbahn von Innsbruck nach Landeck und der endgültigen Fertigstellung der Arlbergbahn bis Bludenz 1884 inklusive dem Tunneldurchschlag durch den Arlberg war Innsbruck endgültig wieder zum Verkehrsknotenpunkt zwischen Deutschland und Italien, Frankreich, der Schweiz und Wien geworden. 1904 wurde die Stubaitalbahn, 1912 die Mittenwaldbahn eröffnet. Beide Projekte plante Josef Riehl (1842 – 1917).

Die Eisenbahn war das am direktesten spürbare Merkmal des Fortschritts für einen großen Teil der Bevölkerung. Die Bahnviadukte, die aus Höttinger Breccie aus dem nahen Steinbruch errichtet wurden, setzten der Stadt im Osten Richtung Pradl ein physisches und sichtbares Ende. Aber nicht nur aus einer rein technischen Perspektive veränderte die Bahn das Land. Sie brachte einen immensen gesellschaftlichen Wandel. Arbeitskräfte, Studenten, Soldaten und Touristen strömten in großer Zahl in die Stadt und brachten neue Lebensentwürfe und Ideen mit. Josef Leitgeb beschrieb den Wandel in seinem Roman Das unversehrte Jahr folgendermaßen:

„Zwar hatte die Eisenbahn schon damals viele landfremde Leute auch nach Wilten gezogen, sie wohnten in den neuen hohen Häusern, die überall aus dem Boden schossen, auf dem seit Jahrhunderten das Korn gewachsen war, aber sie wurden noch als Zugereiste empfunden, ihre tschechischen, slowenischen und ungarischen Namen wollten sich nicht in die Klänge fugen, die man gewohnt war. Sie kleideten sich in das billige Zeug, das man fertig und auf Raten zu kaufen bekam, mieden die Gottesdienste und besuchten dafür Versammlungen, in denen sich die eingesessenen Bürger nicht zurechtgefunden hatten. Bei Licht besehen waren es stille, arbeitsame, sparende Leute, die aus den großen Städten und dem flachen Lande halt andere Lebensformen mitgebracht hatten, und wer sie scheel ansah, konnte kein anderes Recht dafür in Anspruch nehmen, als das er für seine Gemütlichkeit keine Zuschauer brauchte. Doch war die Ablehnung der Zugewanderten durch die Einheimischen damals noch deutlich fühlbar; der Vater hatte einmal eine Predigt gehört, in der der Pfarrer versicherte, alle Menschen konnten der ewigen Seligkeit teilhaft werden, „auch Räuber und Mörder, ja sogar Eisenbahner.“

The Die Bundesbahndirektion der K.u.K. General-Direction der österreichischen Staatsbahnen in Innsbruck war eine von nur drei Direktionen in Cisleithanien. Neue soziale Schichten entstanden durch die Bahn als Arbeitgeber. Es bedurfte Menschen aller Bevölkerungsschichten, um den Bahnbetrieb am Laufen zu halten. Arbeiter und Handwerker konnten bei der Bahn, ähnlich wie in der staatlichen Verwaltung oder dem Militär, sozial aufsteigen. Neue Berufe wie Bahnwärter, Schaffner, Heizer oder Lokführer entstanden. Bei der Bahn zu arbeiten, brachte ein gewisses Prestige mit sich. Nicht nur war man ein Teil der modernsten Branche der Zeit, die Titel und Uniformen machten aus Angestellten und Arbeitern Respektpersonen. Bis 1870 stieg die Einwohnerzahl Innsbrucks vor allem wegen der Wirtschaftsimpulse, die die Bahn brachte von 12.000 auf 17.000 Menschen. Lokale Produzenten profitieren von der Möglichkeit der kostengünstigen und schnellen Warenein- und Ausfuhren. Der Arbeitsmarkt veränderte sich. Vor der Eröffnung der Bahnlinien waren 9 von 10 Tirolern in der Landwirtschaft tätig. Mit der Eröffnung der Brennerbahn sank dieser Wert auf unter 70%. Das neue Verkehrsmittel trug zur gesellschaftlichen Demokratisierung und Verbürgerlichung bei. Nicht nur für wohlhabende Touristen, auch für Untertanen, die nicht der Upper Class angehörten, wurden mit der Bahn Ausflüge in die Umgebung möglich. Neue Lebensmittel veränderten den Speiseplan der Menschen. Erste Kaufhäuser entstanden mit dem Erscheinen von Konsumartikeln, die vorher nicht verfügbar waren. Das Erscheinungsbild der Innsbrucker wandelte sich mit neuer, modischer Kleidung, die für viele zum ersten Mal erschwinglich wurde. Der Bahnhofsvorplatz in Innsbruck wurde zu einem der neuen Zentren der Stadt. Die modernen Hotels waren nun nicht mehr in der Altstadt, sondern hier zu finden. Nicht allen war diese Entwicklung allerdings recht. Die Schifffahrt am Inn, bis dahin ein wichtiger Verkehrsweg, kam beinahe umgehend zum Erliegen. Der ohnehin nach 1848 schwer gerupfte Kleinadel und besonders strenge Kleriker befürchteten den Kollaps der heimischen Landwirtschaft und den endgültigen Sittenverfall durch die Fremden in der Stadt.

The railway was worth its weight in gold for tourism. It was now possible to reach the remote and exotic mountain world of the Tyrolean Alps. Health resorts such as Igls and entire valleys such as the Stubaital, as well as Innsbruck city transport, benefited from the development of the railway. 1904 years later, the Stubai Valley Railway was the first Austrian railway with alternating current to connect the side valley with the capital. On 24 December 1904, 780,000 crowns, the equivalent of around 6 million euros, were subscribed as capital stock for tram line 1. In the summer of the following year, the line connected the new districts of Pradl and Wilten with Saggen and the city centre. Three years later, Line 3 opened the next inner-city public transport connection, which only ran to the remote village in 1942 after Amras was connected to Innsbruck.

The railway was also of great importance to the military. As early as 1866, at the Battle of Königgrätz between Austria and Prussia, it was clear how important troop transport would be in the future. Until 1918, Austria was a huge empire that stretched from Vorarlberg and Tyrol in the south-west to Galicia, an area in what is now Poland, and Ukraine in the east. The Brenner Railway was needed to reinforce the turbulent southern border with its new neighbour, the Kingdom of Italy. Tyrolean soldiers were also deployed in Galicia during the first years of the First World War until Italy declared war on Austria. When the front line was opened up in South Tyrol, the railway was important for moving troops quickly from the east of the empire to the southern front.

Carl von Etzel, who did not live to see the opening of the Brenner railway, is commemorated today by Ing.-Etzel-Straße in Saggen along the railway viaducts. Josef Riehl is commemorated by Dr.-Ing.-Riehl-Straße in Wilten near the Westbahnhof railway station. There is also a street dedicated to Achilles Thommen. As a walker or cyclist, you can cross the Karwendel Bridge in the Höttinger Au one floor below the Karwendel railway and admire the steel framework. You can get a good impression of the golden age of the railway by visiting the ÖBB administration building in Saggen or the listed Westbahnhof railway station in Wilten. In the viaduct arches in Saggen, you can enjoy Innsbruck's nightlife in one of the many pubs covered by history.

The Red Bishop and Innsbruck's moral decay

In the 1950s, Innsbruck began to recover from the crisis and war years of the first half of the 20th century. On 15 May 1955, Federal Chancellor Leopold Figl declared with the famous words "Austria is free" and the signing of the State Treaty officially marked the political turning point. In many households, the "political turnaround" became established in the years known as Economic miracle moderate prosperity. Between 1953 and 1962, annual economic growth of over 6% allowed an increasing proportion of the population to dream of things that had long been exotic, such as refrigerators, their own bathroom or even a holiday in the south. This period brought not only material but also social change. People's desires became more outlandish with increasing prosperity and the lifestyle conveyed in advertising and the media. The phenomenon of a new youth culture began to spread gently amidst the grey society of small post-war Austria. The terms Teenager and "latchkey kid" entered the Austrian language in the 1950s. The big world came to Innsbruck via films. Cinema screenings and cinemas had already existed in Innsbruck at the turn of the century, but in the post-war period the programme was adapted to a young audience for the first time. Hardly anyone had a television set in their living room and the programme was meagre. The numerous cinemas courted the public's favour with scandalous films. From 1956, the magazine BRAVO. For the first time, there was a medium that was orientated towards the interests of young people. The first issue featured Marylin Monroe, with the question: „Marylin's curves also got married?“ The big stars of the early years were James Dean and Peter Kraus, before the Beatles took over in the 60s. After the Summer of Love Dr Sommer explained about love and sex. The church's omnipotent authority over the moral behaviour of adolescents began to crumble, albeit only slowly. The first photo love story with bare breasts did not follow until 1982. Until the 1970s, the opportunities for adolescent Innsbruckers were largely limited to pub parlours, shooting clubs and brass bands. Only gradually did bars, discos, nightclubs, pubs and event venues open. Events such as the 5 o'clock tea dance at the Sporthotel Igls attracted young people looking for a mate. The Cafe Central became the „second home of long-haired teenagers“, as the Tiroler Tageszeitung newspaper stated with horror in 1972. Establishments like the Falconry cellar in the Gilmstraße, the Uptown Jazzsalon in Hötting, the jazz club in the Hofgasse, the Clima Club in Saggen, the Scotch Club in the Angerzellgasse and the Tangent in Bruneckerstraße had nothing in common with the traditional Tyrolean beer and wine bar. The performances by the Rolling Stones and Deep Purple in the Olympic Hall in 1973 were the high point of Innsbruck's spring awakening for the time being. Innsbruck may not have become London or San Francisco, but it had at least breathed a breath of rock'n'roll. What is still anchored in cultural memory today as the '68 movement took place in the Holy Land hardly took place. Neither workers nor students took to the barricades in droves. The historian Fritz Keller described the „68 movement in Austria as "Mail fan“. Nevertheless, society was quietly and secretly changing. A look at the annual charts gives an indication of this. In 1964, it was still Chaplain Alfred Flury and Freddy with „Leave the little things“ and „Give me your word" and the Beatles with their German version of "Come, give me your hand who dominated the Top 10, musical tastes changed in the years leading up to the 1970s. Peter Alexander and Mireille Mathieu were still to be found in the charts. From 1967, however, it was international bands with foreign-language lyrics such as The Rolling Stones, Tom Jones, The Monkees, Scott McKenzie, Adriano Celentano or Simon and Garfunkel, who occupied the top positions in great density with partly socially critical lyrics.

This change provoked a backlash. The spearhead of the conservative counter-revolution was the Innsbruck bishop Paulus Rusch. Cigarettes, alcohol, overly permissive fashion, holidays abroad, working women, nightclubs, premarital sex, the 40-hour week, Sunday sporting events, dance evenings, mixed sexes in school and leisure - all of these things were strictly abhorrent to the strict churchman and follower of the Sacred Heart cult. Peter Paul Rusch was born in Munich in 1903 and grew up in Vorarlberg as the youngest of three children in a middle-class household. Both parents and his older sister died of tuberculosis before he reached adulthood. At the young age of 17, Rusch had to fend for himself early on in the meagre post-war period. Inflation had eaten up his father's inheritance, which could have financed his studies, in no time at all. Rusch worked for six years at the Bank for Tyrol and Vorarlberg, in order to finance his theological studies. He entered the Collegium Canisianum in 1927 and was ordained a priest of the Jesuit order six years later. His stellar career took the intelligent young man first to Lech and Hohenems as chaplain and then back to Innsbruck as head of the seminary. In 1938, he became titular bishop of Lykopolis and Apostolic Administrator for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. As the youngest bishop in Europe, he had to survive the harassment of the church by the National Socialist rulers. Although his critical attitude towards National Socialism was well known, Rusch himself was never imprisoned. Those in power were too afraid of turning the popular young bishop into a martyr.

After the war, the socially and politically committed bishop was at the forefront of reconstruction efforts. He wanted the church to have more influence on people's everyday lives again. His father had worked his way up from carpenter to architect and probably gave him a soft spot for the building industry. He also had his own experience at BTV. Thanks to his training as a banker, Rusch recognised the opportunities for the church to get involved and make a name for itself as a helper in times of need. It was not only the churches that had been damaged in the war that were rebuilt. The Catholic Youth under Rusch's leadership, was involved free of charge in the construction of the Heiligjahrsiedlung in the Höttinger Au. The diocese bought a building plot from the Ursuline order for this purpose. The loans for the settlers were advanced interest-free by the church. Decades later, his rustic approach to the housing issue would earn him the title of "Red Bishop" to the new home. In the modest little houses with self-catering gardens, in line with the ideas of the dogmatic and frugal "working-class bishop", 41 families, preferably with many children, found a new home.

By alleviating the housing shortage, the greatest threats in the Cold WarCommunism and socialism, from his community. The atheism prescribed by communism and the consumer-orientated capitalism that had swept into Western Europe from the USA after the war were anathema to him. In 1953, Rusch's book "Young worker, where to?". What sounds like revolutionary, left-wing reading from the Kremlin showed the principles of Christian social teaching, which castigated both capitalism and socialism. Families should live modestly in order to live in Christian harmony with the moderate financial means of a single father. Entrepreneurs, employees and workers were to form a peaceful unity. Co-operation instead of class warfare, the basis of today's social partnership. To each his own place in a Christian sense, a kind of modern feudal system that was already planned for use in Dollfuß's corporative state. He shared his political views with Governor Eduard Wallnöfer and Mayor Alois Lugger, who, together with the bishop, organised the Holy Trinity of conservative Tyrol at the time of the economic miracle. Rusch combined this with a latent Catholic anti-Semitism that was still widespread in Tyrol after 1945 and which, thanks to aberrations such as the veneration of the Anderle von Rinn has long been a tradition.

Education and training were of particular concern to the pugnacious Jesuit. The social formation across all classes by the soldiers of Christ could look back on a long tradition in Innsbruck. In 1909, the Jesuit priest and former prison chaplain Alois Mathiowitz (1853 - 1922) founded the Peter-Mayr-Bund. His approach was to put young people on the right path through leisure activities and sport and adults from working-class backgrounds through lectures and popular education. The workers' youth centre in Reichenauerstraße, which was built under his aegis, still serves as a youth centre and kindergarten today. Rusch also had experience with young people. In 1936, he was elected regional field master of the scouts in Vorarlberg. Despite a speech impediment, he was a charismatic guy and extremely popular with his young colleagues and teenagers. In his opinion, only a sound education under the wing of the church according to the Christian model could save the salvation of young people. In order to give young people a perspective and steer them in an orderly direction with a home and family, the Youth building society savings strengthened. In the parishes, kindergartens, youth centres and educational institutions such as the House of encounter on Rennweg in order to have education in the hands of the church right from the start. The vast majority of the social life of the city's young people did not take place in disreputable dive bars. Most young people simply didn't have the money to go out regularly. Many found their place in the more or less orderly channels of Catholic youth organisations. Alongside the ultra-conservative Bishop Rusch, a generation of liberal clerics grew up who became involved in youth work. In the 1960s and 70s, two church youth movements with great influence were active in Innsbruck. Sigmund Kripp and Meinrad Schumacher were responsible for this, who were able to win over teenagers and young adults with new approaches to education and a more open approach to sensitive topics such as sexuality and drugs. The education of the elite in the spirit of the Jesuit order was provided in Innsbruck from 1578 by the Marian Congregation. This youth organisation, still known today as the MK, took care of secondary school pupils. The MK had a strict hierarchical structure in order to give the young Soldaten Christi obedience from the very beginning. In 1959, Father Sigmund Kripp took over the leadership of the organisation. Under his leadership, the young people, with financial support from the church, state and parents and with a great deal of personal effort, set up projects such as the Mittergrathütte including its own material cable car in Kühtai and the legendary youth centre Kennedy House in the Sillgasse. Chancellor Klaus and members of the American embassy were present at the laying of the foundation stone for this youth centre, which was to become the largest of its kind in Europe with almost 1,500 members, as the building was dedicated to the first Catholic president of the USA, who had only recently been assassinated.

The other church youth organisation in Innsbruck was Z6. The city's youth chaplain, Chaplain Meinrad Schumacher, took care of the youth organisation as part of the Action 4-5-6 to all young people who are in the MK or the Catholic Student Union had no place. Working-class children and apprentices met in various youth centres such as Pradl or Reichenau before the new centre, also built by the members themselves, was opened at Zollerstraße 6 in 1971. Josef Windischer took over the management of the centre. The Z6 already had more to do with what Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda were doing on the big screen on their motorbikes in Easy Rider was shown. Things were rougher here than in the MK. Rock gangs like the Santanas, petty criminals and drug addicts also spent their free time in Z6. While Schumacher reeled off his programme upstairs with the "good" youngsters, Windischer and the Outsiders the basement to help the lost sheep as much as possible.

At the end of the 1960s, both the MK and the Z6 decided to open up to non-members. Girls' and boys' groups were partially merged and non-members were also admitted. Although the two youth centres had different target groups, the concept was the same. Theological knowledge and Christian morals were taught in a playful, age-appropriate environment. Sections such as chess, football, hockey, basketball, music, cinema films and a party room catered to the young people's needs for games, sport and the removal of taboos surrounding their first sexual experiences. The youth centres offered a space where young people of both sexes could meet. However, the MK in particular remained an institution that had nothing to do with the wild life of the '68ers, as it is often portrayed in films. For example, dance courses did not take place during Advent, carnival or on Saturdays, and for under-17s they were forbidden.

Nevertheless, the youth centres went too far for Bishop Rusch. The critical articles in the MK newspaper We discuss, which reached a circulation of over 2,000 copies, found less and less favour. Solidarity with Vietnam was one thing, but criticism of marksmen and the army could not be tolerated. After years of disputes between the bishop and the youth centre, it came to a showdown in 1973. When Father Kripp published his book Farewell to tomorrow in which he reported on his pedagogical concept and the work in the MK, there were non-public proceedings within the diocese and the Jesuit order against the director of the youth centre. Despite massive protests from parents and members, Kripp was removed. Neither the intervention within the church by the eminent theologian Karl Rahner, nor a petition initiated by the artist Paul Flora, nor regional and national outrage in the press could save the overly liberal Father from the wrath of Rusch, who even secured the papal blessing from Rome for his removal from office.

In July 1974, the Z6 was also temporarily over. Articles about the contraceptive pill and the Z6 newspaper's criticism of the Catholic Church were too much for the strict bishop. Rusch had the keys to the youth centre changed without further ado, a method he also used at the Catholic Student Union when it got too close to a left-wing action group. The Tiroler Tageszeitung noted this in a small article on 1 August 1974:

"In recent weeks, there had been profound disputes between the educators and the bishop over fundamental issues. According to the bishop, the views expressed in "Z 6" were "no longer in line with church teaching". For example, the leadership of the centre granted young people absolute freedom of conscience without simultaneously recognising objective norms and also permitted sexual relations before marriage."

It was his adherence to conservative values and his stubbornness that damaged Rusch's reputation in the last 20 years of his life. When he was consecrated as the first bishop of the newly founded diocese of Innsbruck in 1964, times were changing. The progressive with practical life experience of the past was overtaken by the modern life of a new generation and the needs of the emerging consumer society. The bishop's constant criticism of the lifestyle of his flock and his stubborn adherence to his overly conservative values, coupled with some bizarre statements, turned the co-founder of development aid into a Brother in needthe young, hands-on bishop of the reconstruction, from the late 1960s onwards as a reason for leaving the church. His concept of repentance and penance took on bizarre forms. He demanded guilt and atonement from the Tyroleans for their misdemeanours during the Nazi era, but at the same time described the denazification laws as too far-reaching and strict. In response to the new sexual practices and abortion laws under Chancellor Kreisky, he said that girls and young women who have premature sexual intercourse are up to twelve times more likely to develop cancer of the mother's organs. Rusch described Hamburg as a cesspool of sin and he suspected that the simple minds of the Tyrolean population were not up to phenomena such as tourism and nightclubs and were tempted to immoral behaviour. He feared that technology and progress were making people too independent of God. He was strictly against the new custom of double income. People should be satisfied with a spiritual family home with a vegetable garden and not strive for more; women should concentrate on their traditional role as housewife and mother.

In 1973, after 35 years at the head of the church community in Tyrol and Innsbruck, Bishop Rusch was made an honorary citizen of the city of Innsbruck. He resigned from his office in 1981. In 1986, Innsbruck's first bishop was laid to rest in St Jakob's Cathedral. The Bishop Paul's Student Residence The church of St Peter Canisius in the Höttinger Au, which was built under him, commemorates him.

After its closure in 1974, the Z6 youth centre moved to Andreas-Hofer-Straße 11 before finding its current home in Dreiheiligenstraße, in the middle of the working-class district of the early modern period opposite the Pest Church. Jussuf Windischer remained in Innsbruck after working on social projects in Brazil. The father of four children continued to work with socially marginalised groups, was a lecturer at the Social Academy, prison chaplain and director of the Caritas Integration House in Innsbruck.

The MK also still exists today, even though the Kennedy House, which was converted into a Sigmund Kripp House was renamed, no longer exists. In 2005, Kripp was made an honorary citizen of the city of Innsbruck by his former sodalist and later deputy mayor, like Bishop Rusch before him.

The good and the bad of Innsbruck

The arches, that's where the good Innsbruckers don't go in Innsbruck. Unless they are drunk because they were somewhere else with the less good Innsbruckers beforehand, where the less good ones persuaded them to drink alcohol, which the good ones didn't want to drink, as they will tell their partner, spouse, guardian or breadwinner when they come home the next day, remorseful for their weakness and upset about the misfortune they suffered at the hands of the less good Innsbruckers. But who cares, the good Innsbruckers don't go there, because everything that doesn't meet anywhere else meets in the arches: men in shirts, women in dresses, women in trousers, men in kilts, men with long hair, women with dyed hair, rockers, hackers, students, young farmers, sportsmen, musicians, punks - in short, so that we can cope - everything. It's scary. And there's not just drinking, there's also dealing, beating and stabbing. I haven't seen the beatings, at least not any more than in other pubs where drunk people get together, and no stabbings anyway, but it's in the papers and that's probably how it is.

Sometimes, it used to be more often, because I'm already old, when I get talking to a good Innsbrucker in a beer mood, and the conversation turns to arcs at some point during the evening and how bad they are, then I like to explain that if you follow Einstein's theory of space-time, which I don't understand but still like to bring up to impress the good Innsbruckers, who don't understand it either, then arcs are neither good nor bad, but relative at best. Then nobody understands it and I have to explain it. The arcs are relative because they have neither a beginning nor an end in terms of time or space, neither on a small scale nor on a large scale.

Not in the short term, because the arches never really close. When the last bar closes, the first one opens again. Brennpunkt sells its coffee to hipsters more in the morning than in the evening. And not in the big time either, because the things that happen there repeat themselves like in an endless time loop, except that everything gets worse, of course. Because when I was younger, everything was better than it is now that my son is starting to go out, the music anyway and it wasn't as expensive and we didn't dress as stupidly or talk as stupidly to each other as the boys do today. And when I tell him about the old days and how great everything was, especially in the arches, then of course he listens to me in awe, just like I used to listen to my dad when he told me how everything was better in the old days.

And it's not just the arches that are in this time loop, what happens afterwards because of the arches doesn't change either, you can't get that old. My mum used to complain when I was younger and lived at home, well, with my parents, because you live at home anyway, when I came home early in the morning and drunk. "Have you been drinking in the arches again, ha?". When I moved out and had a girlfriend who didn't drink alcohol at all and therefore never went to the arches, I didn't go there as often, but she always complained when it happened. Now I have a friend who used to go to the arches and when I go there now, she goes with me and if you think that hardly anyone can complain, then you're wrong, because the complaint is just because she has a headache and a hangover the next day because of me, because she had to go with me. So it's no use growing up, if you go to the arches, whether alone or not, you'll get told off.

And the spatial aspect is also relative, because the arches have two beginnings and two ends, and you can't really say where they begin and end, because that depends on where you go in and then leave again when you've finished. For me, the arches start at the front, at Sillpark, where the Viaduktstüberl used to be, a pub that always had dirty windows with Unterberg advertisements and where it could happen that someone would get wild very early in the evening, because where the arches start, people started drinking alcohol very early. Now, by the way, there's a restaurant in this arch where families are supposed to go.

For someone else, the arches certainly start at the back of the Sillzwickl where the Outsider Motorcycle Club has its clubhouse, although I find that strange, but as a cosmopolitan person you have to respect this wrong opinion. I was there once at a 150th birthday party. When I turned 30, I had a party with four friends who were also turning 30. That was also funny, by the way, especially how the girlfriend of one of my friends cuddled with one of the motorbike waiters, that was the end of the story.

But it's better to go back to the beginning. Here's the thing about the bends. If you count the last bend after the Outsider, which is actually a pass, there are 175. 175 bends spread over 1.7 kilometres. I know this because I measured it with my sports watch. Between the Outsider and the next restaurant, the Cafe zum Mo In the 103 bend, the first 650 metres, or the last, as you see it, are actually only car and moped garages and the Veloflott for bicycles, i.e. mobility, and I'm more interested in the alcoholic side of the bends. And the interesting part is the first one, because there are bars and pubs along this kilometre.

The first is the Little Rock, which looks a bit like a saloon and where we used to say, when everything was better, that we wouldn't go in there because it's very similar to the Down Under anyway, except that the Down Under is much cooler. It's just a shame that the Down Under no longer exists. When I was standing in front of the door and realised that it was closed, it was like a Catholic when the Pope dies, and the Catholic doesn't notice and then at some point when he's standing in Rome he's told: "The Pope has died." That's probably how I looked the moment I found out, with a very surprised and sad face, because Down Under I've drunk a lot of beer up at the tables and at the bar. And when a place like the Down Under no longer exists, you realise - Holla, I'm not young anymore either. It's like when your kindergarten is torn down and it's been so long since you were there that you can't even remember it. The difference between Down Under and kindergarten is that there was no tequila in kindergarten. And the music was always good there too, in the Down Under, not in the kindergarten. It was so loud that you could still have a conversation. That's why you always went to Down Under, where you could still talk and weren't completely drunk, and only later to PMK, where there are always concerts and the music is louder. What's more, people were always more relaxed at Down Under than at PMK, where everyone was always stressed.

If you now think that the PMK was the opposite of Down Under, then that's wrong. The opposite of PMK is on the other side of the arches, where the new railway station is now. The arches have their own railway station, as they should. The opposite of PMK, with all the alternatives and left-wingers, is both geographically and ideologically the St Andrew's parlourwhere the landlord, Ander, serves his Indians, most of whom have spent too many summers and winters in the arches, beer and Ramazzotti to the sound of pop music like a chieftain.

Next to the Andreasstüberl is Shakespeare's, where you might also hear pop music, because they often sing karaoke there and if the DJ is in a good mood, he might sing a pop song, even though he himself is more of a metal fan.

If you then take everything between the Little Rock and the Café zum Mo, then everything is relative, as Einstein says, but there is still a centre. Because no matter how much of a physicist you are, in the real world, which both the good and the less good Innsbrucker understand, there needs to be a centre. And in the arches, this centre is the plateau. Of course, like everything else, the Plateau has got worse because there's nothing going on there any more, which could of course be because I can't stand it until three o'clock any more, there was never anything going on there before, but I think it used to be better. It doesn't really matter, because the plateau is really the definition of spacetime, at least as far as I understand it. How else can it be that there is no time, the small space always looks much bigger and everything is relatively unimportant when you're in there. For example, you go in sometime after midnight and leave again at half past midnight. Half past midnight is the time when it's already light outside and the birds are chirping and the good people of Innsbruck, who weren't trapped in space-time, go to work and it's still dark on the plateau because it's only just past midnight there.

When I was young, I needed money, so I even spent two weeks during the Christmas holidays in the Plateau doing the accounts, scrubbing the floor and cleaning the toilets. So when I went in in the morning, the waiters were still sitting inside drinking and smoking and I was sober and wanted to clean, but I couldn't because in the Plateau's space-time, the drunks have priority. It can be there outside the door, but in this small room, it's always halfway there.

And when the good people of Innsbruck always grumble about the Plateau and the Andreasstüberl and the PMK and the other arches, then I have to say that I think it's great that we have something in the city where everyone meets and everyone is equal and even the space and time are no longer quite so exact and it's OK if it gets halfway. So!