Maria Hilf Innsbruck!

Maria help Innsbruck!

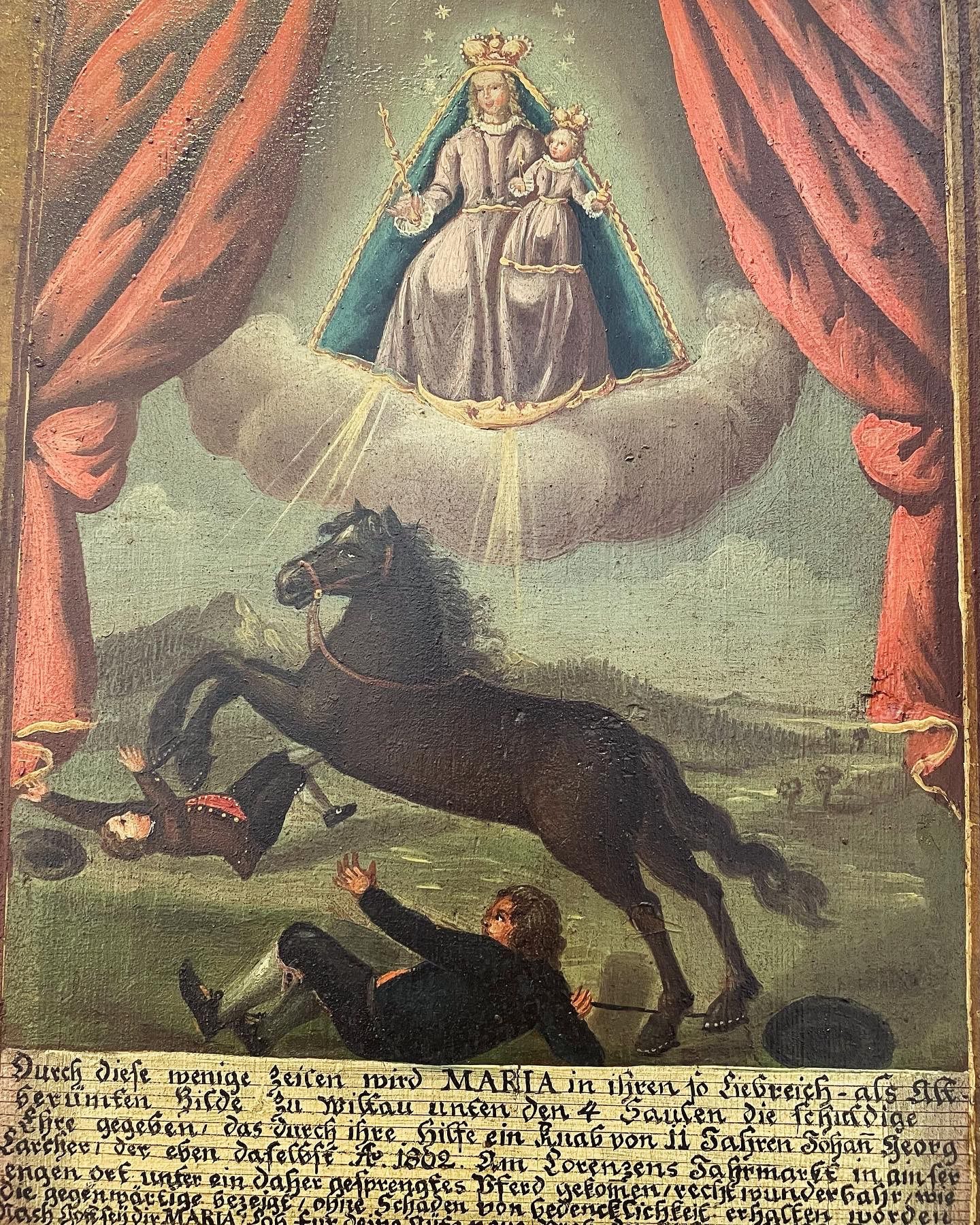

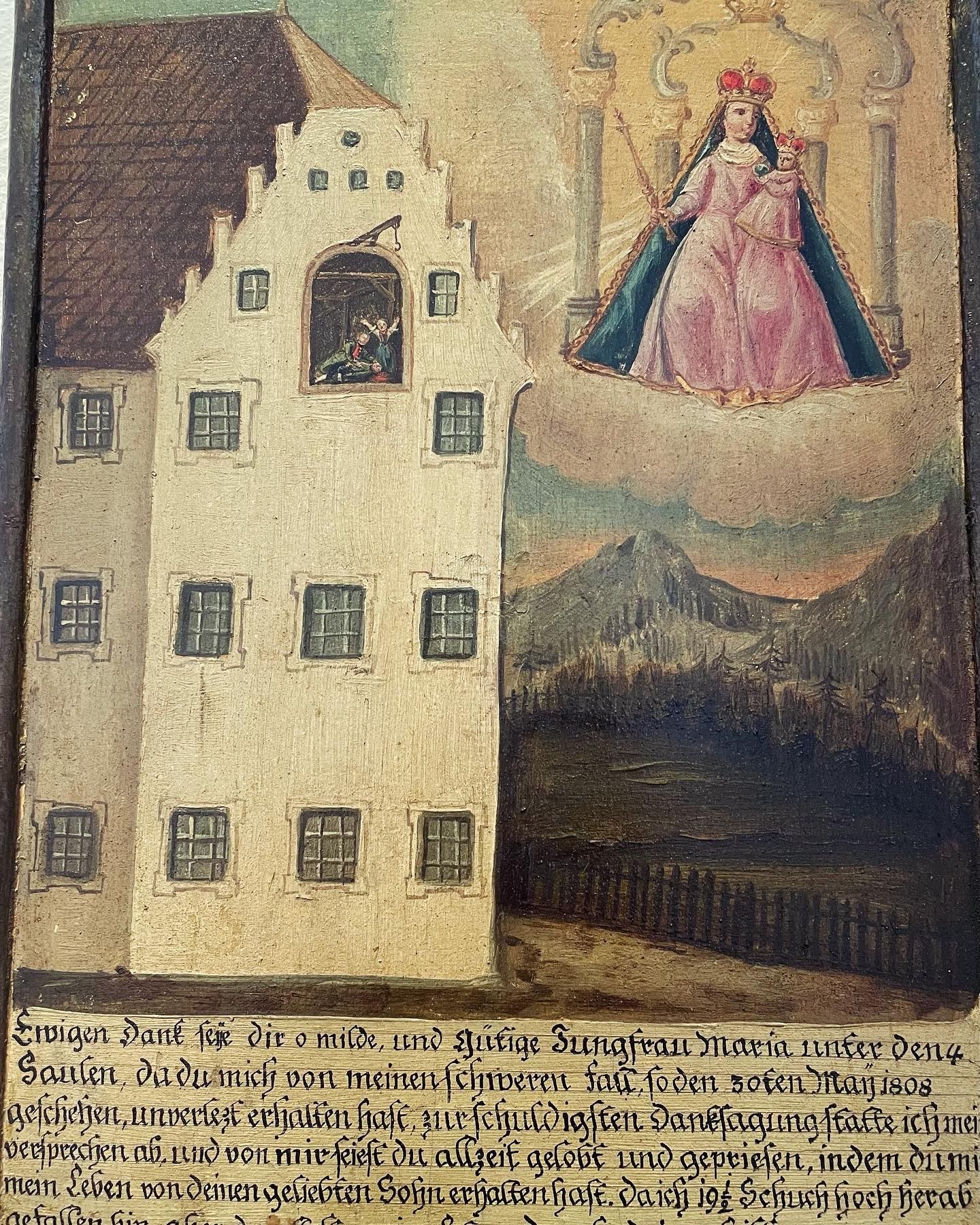

The veneration of saints and popular piety always walked a fine line between faith, superstition and magic. In the Alps, where people were more exposed to the almost inexplicable environment than in other regions, this form of faith took on remarkable and often bizarre forms. Saints were invoked for help with various everyday tasks. St Anne was supposed to protect the house and hearth, while St Notburga of Rattenberg, who was particularly popular in Tyrol, was prayed to for a good harvest. When fertilisers and agricultural machinery were increasingly used for this purpose, she rose to become the patron saint of women wearing traditional costumes. Miners entrusted their fate in their dangerous job underground to St Barbara and St Bernard. The chapel at the manor houses in Halltal near Innsbruck provides a fascinating insight into the world of faith between Begging spirit and worship of various local patron saints. The saint who still outshines all others in terms of veneration is Mary. From the consecration of herbs at the Assumption of Mary to the right-turning water in Maria Waldrast at the foot of the Serles and votive images in churches and chapels, she is a favourite permanent guest in popular piety. If you take a careful stroll through Innsbruck, you will find a special image on the facades of buildings time and again: the Gnadenbild Mariahilf by Lucas Cranach (ca. 1472 - 1553).

Cranach's Madonna is one of the most popular and most frequently copied depictions of Mary in the Alpine region. The painting is a reinterpretation of the classic iconographic Mother of God. Similar to the Mona Lisa da Vinci, which was painted at a similar time, Mary smiles mischievously at the viewer. Cranach dispensed with any form of sacralisation such as a crescent moon or halo and has her appear in contemporary everyday clothing. The red-blonde hair of mother and child transports her from Palestine to Europe. The saint and virgin Mary became an ordinary woman with a child from the upper middle class of the 16th century.

The creation, journey and veneration of the Mariahilf miraculous image tell the story of the Reformation, Counter-Reformation and popular piety in the German lands in miniature. The odyssey of the painting, which measures just 78 x 47 cm, began in what is now Thuringia at the royal court, one of the cultural centres of Europe at the time. Elector Frederick III of Saxony (1463 - 1525) was a pious man. He owned one of the most extensive collections of relics of the time. Despite his deep roots in the popular belief in relics and his pronounced penchant for Marian devotion, he supported Martin Luther in 1518 not only for religious reasons, but also for reasons of power politics. Free passage from the powerful prince and accommodation at Wartburg Castle enabled Luther to work on the German translation of the Holy Scriptures and his vision of a new, reformed church.

As was customary at the time, Friedrich also had a Art Director in his entourage. Lucas Cranach had been a court painter in Wittenberg since 1515. Like other painters of his time, Cranach was not only extremely productive, but also extremely enterprising. In addition to his artistic activities, he ran a pharmacy and a wine tavern in Wittenberg. Thanks to his financial prosperity and reputation, he was mayor of the town from 1528. Cranach was regarded as a quick painter with great output. He recognised art as a medium for capturing and disseminating the spirit of the times. Like Albrecht Dürer, he created popular works with a wide reach. His portraits of the high society of the time still characterise our image of celebrities today, such as those of his employer Frederick, Maximilian I, Martin Luther and his colleague Dürer.

Cranach and the church critics Philipp Melanchthon and Martin Luther met at Wittenberg Castle. It was through this acquaintance at the latest that the artist became a supporter of the new, reformed Christianity, which did not yet have an official manifestation. The ambiguities in the religious beliefs and practices of this period before the official schism are reflected in Cranach's works. Despite Luther and Melanchthon's rejection of the veneration of saints, the cult of the Virgin Mary and iconographic representations in churches, Cranach continued to paint for his patrons according to their taste.

Just as unclear as the transition from one denomination to another in the 16th century is the date of origin of the The miraculous image of Mariahilf. Cranach painted it sometime between 1510 and 1537 either for the household of Frederick's sister-in-law, Duchess Barbara of Saxony, or for the Church of the Holy Cross in Dresden. Art experts are still divided today. The friendship between Cranach and Martin Luther suggests that Cranach painted it after his conversion to Lutheranism and that this secularised depiction of a mother and child is an expression of a new religious world view. However, it is entirely possible that the business-minded artist painted the picture without any ideological background, but as an expression of the fashion of the time even before Luther's arrival in Wittenberg.

After Frederick's death, Cranach entered the service of his successor, John Frederick I of Saxony. When his employer was taken prisoner by the emperor after the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547, court painter Cranach followed him to Augsburg and Innsbruck despite his advanced age. After five years in the wake of the hostage, who was probably housed in luxury, Cranach returned to Wittenberg, where he succumbed to his biblical age by the standards of the time.

The Gnadenbild Mariahilf was transferred to the Kunstkammer of the Saxon sovereign during the turbulent years of the confessional wars, probably to save it from destruction by zealous iconoclasts. Almost 65 years later, like its creator before it, it was to find its way to Innsbruck along winding paths. When the art-loving Bishop of Passau from the House of Habsburg was a guest at court in Dresden in 1611, he chose Cranach's miraculous painting as a gift and took it with him to his prince-bishop's residence on the Danube. His cathedral dean saw it there and was so impressed that he had a copy made for his home altar. A pilgrimage cult quickly developed around the picture.

When the Bishop of Passau became Archduke Leopold V of Austria and Prince of Tyrol seven years later, the popular painting moved with its owner to the court in Innsbruck. His Tuscan wife Claudia de Medici kept the cult of the Virgin Mary in the Italian tradition alive even after his death. Both the Servite Church and the Capuchin monastery were given altars and images of the Virgin Mary. However, nothing was more popular than Cranach's miraculous image. In order to protect the city during the Thirty Years' War, the image was often taken from the court chapel and displayed for public veneration. During these mass prayers, the desperate population of Innsbruck shouted a loud "Maria Hilf" ("Mary Help") at the small painting, a practice that had become part of popular belief thanks to the Jesuits. In 1647, at the moment of greatest need, the Tyrolean estates swore to build a church around the painting to protect the country from devastation by Bavarian and Swedish troops. The fact that the reformed depiction of St Mary, painted by a friend of Martin Luther, was invoked to protect the city from Protestant troops is probably not without a certain irony.

Although the Mariahilf church was built, the painting was exhibited in 1650 in the parish church of St Jakob within the safe city walls. The newly built church received a copy made by Michael Waldmann. It was not to be the last of its kind. The motif and Cranach's depiction of the Mother of God became extremely popular and can still be found today not only in churches but also on countless private houses. Art became a mass phenomenon through these copies. The image of the Virgin Mary had migrated from the private property of the Saxon prince to the public sphere. Centuries before Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, Cranach and Dürer had become widely copied artists and their paintings had become part of public space and everyday life. The original of the The miraculous image of Mariahilf may hang in St Jacob's Cathedral, but the copy and the parish that grew up around it gave its name to an entire district.

Sights to see...

Pfarre Mariahilf

Dr.-Sigismund-Epp-Weg

Pradlerstraße

Pradlerstraße

Helblinghaus

Herzog-Friedrich-Straße 10

Mariahilfzeile & Marketplace

Mariahilfstraße / Marketplace

Dom Sankt Jakob

Domplatz

Annasäule

Maria-Theresienstrasse 31