Wilten Abbey & Basilica

Klostergasse 7 / Pastorgasse 2

Wilten Basilica

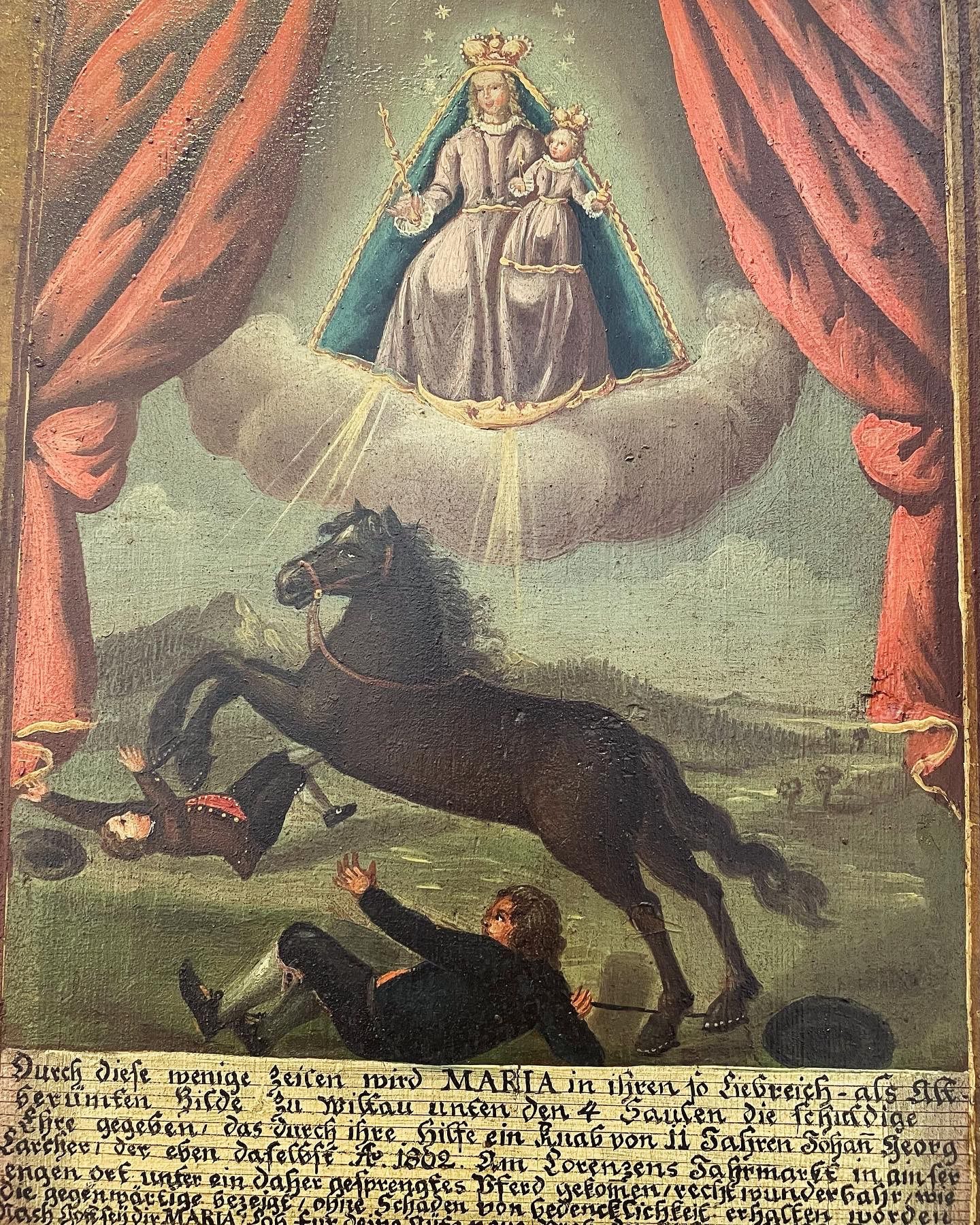

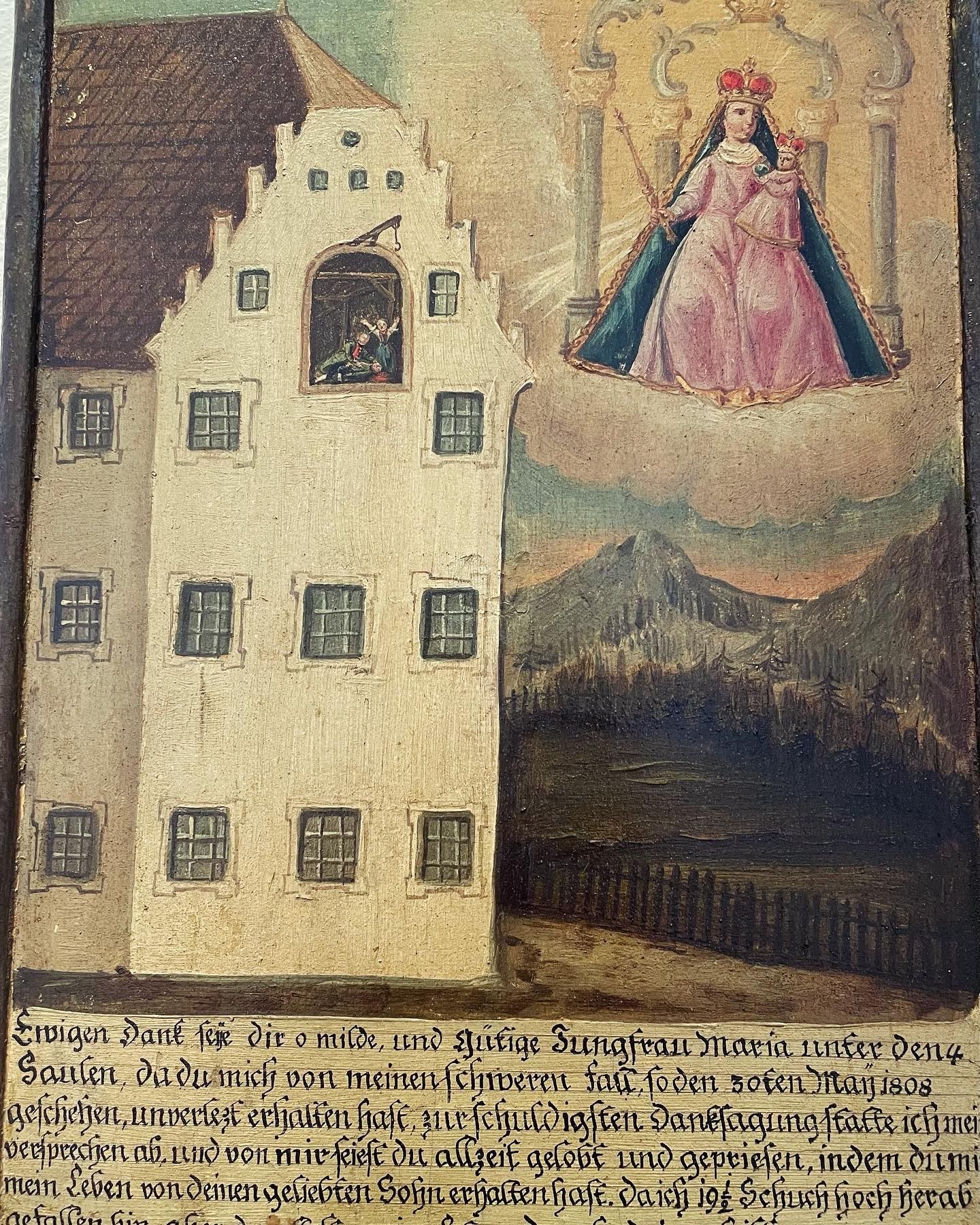

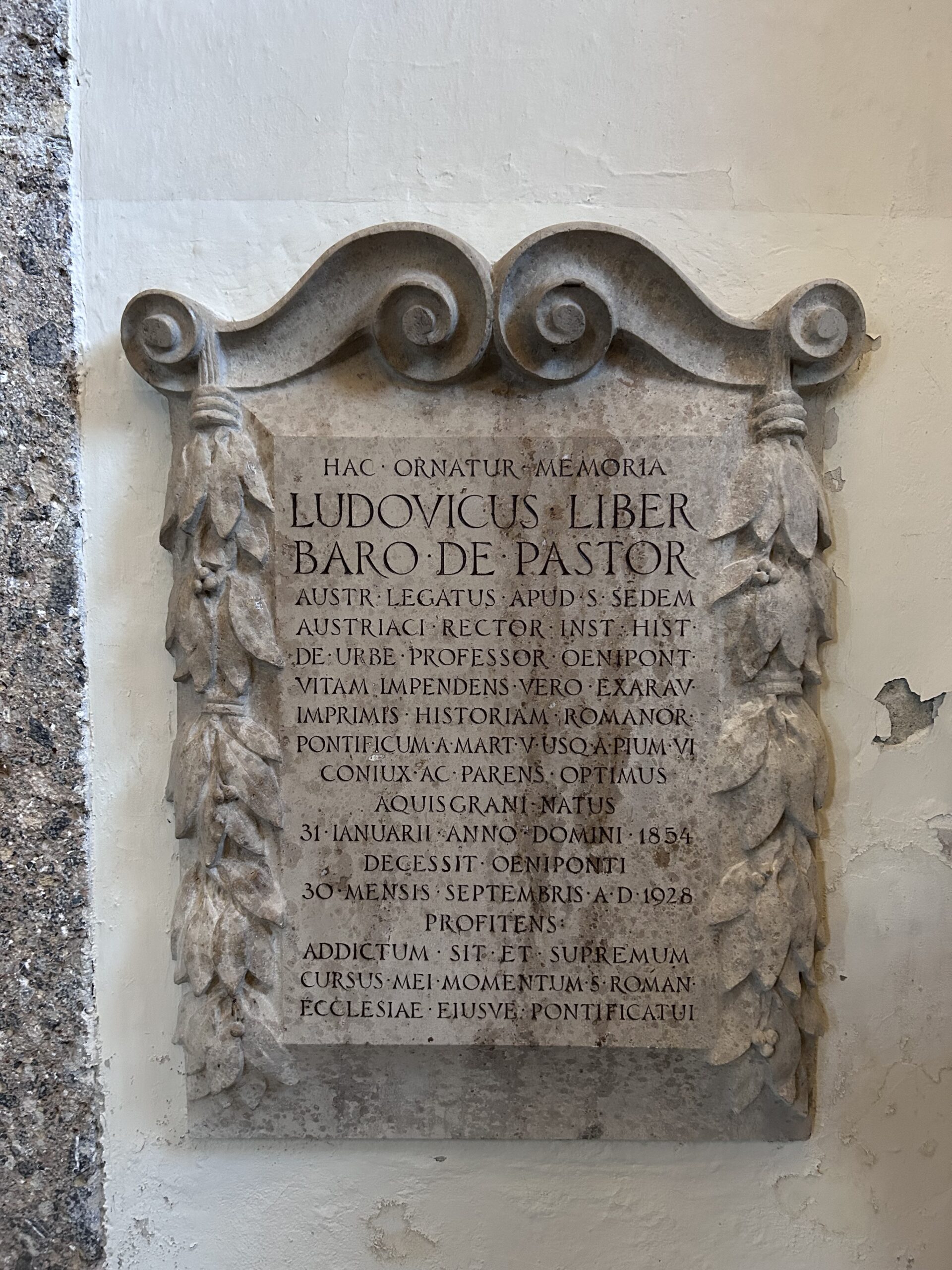

The site of today's Wilten Abbey and the basilica is one of the earliest populated parts of Innsbruck's urban area. At the latest with the elevation of Christianity to a state religion, the institutionalised faith probably also gained a foothold in the Inn Valley. Where the Wilten Basilica stands today was probably already a place of prayer in the 5th century, after Christianity had become the Roman state religion. An approximately 25 metre long and 12 metre wide building from the 5th century has been found under today's baroque church and cemetery. This made the church one of the largest in the region at the time. A church dedicated to St Laurentius was first mentioned in 565. In a document from 1140, the Premonstratensian Order took over the basilica as the parish and baptismal church of the municipality of Wilten. Research assumes that the document is probably a forgery from the 13th century. It was not uncommon in the Middle Ages for documents to be produced retrospectively on the basis of dubious facts. Privilegium Maius in Austrian history. Not only was it difficult or impossible to prove the forgery, but in this case there was often neither reason nor interest in uncovering the true facts. The basilica was probably built as a new Gothic building towards the end of the 12th century and has been a pilgrimage church since 1259. Our Lady or Mary under the four pillars documented. Legend has it that Roman legionaries in the second century are said to have prayed to Our Lady of the Four Pillars for help in times of need. The Xth legion of the Roman army under Emperor Marcus Aurelius is said to have stopped off in Innsbruck after crossing the Alps over the Brenner Pass in 137. Early Christians among the soldiers buried an image of the Mother of God under four trees. A baroque mosaic on the outer wall of the basilica, which shows Mary as the Queen of Heaven with little Jesus on her lap, is a reminder of the legend. Until 1643, the church in Wilten was the parish church of the city of Innsbruck. This meant that high Christian celebrations such as weddings and baptisms could only be held in Wilten, which was an independent parish at the time. After the building was damaged and rebuilt several times, the baroque building was constructed between 1751 and 1755 according to the plans of Joseph Stapf (1711 - 1785), which still stands today on the site of the city's earliest Christian church and is surrounded by a small cemetery. Joseph Stapf was the sculptor responsible for the main entrance made of Höttinger Breccie. The motto of the current Pope Leo XIV „In Illo Uno Unum“ (In that One we are one). The silver lily of the coat of arms symbolises the Virgin Mary, the burning heart of Jesus pierced by an arrow symbolises the loving and flaming divine penetration of the soul and is the emblem of the Augustinian Order. The book symbolises the Bible and the Word of God. High above it is a statue of the Maria Immaculata with a crown of stars. The master builder was Franz de Paula Penz (1707 - 1772). The son of a Wipptal farmer, he was able to study theology due to his talent. Even as a young man, he began to take an interest in architecture and design plans for churches. As an ecclesiastical building director, he oversaw countless new church buildings in Tyrol during the era of extensive baroqueisation. To the left behind the entrance gate is a small side aisle, in which countless Baroque votive images of particularly pious Innsbruck residents can be seen, thanking the Virgin Mary for what has happened or asking for the fulfilment of a wish. Photos commemorate Pope John Paul II's visit to Innsbruck in June 1988. In front of the entrance to the room, two memorial stones commemorate the Wilten-born politician Ferdinand Ernst Maria Anton Graf von Bissingen-Nippenburgn (1749 - 1831) and his wife, who found their final resting place in the basilica. Count Ferdinand was not only governor of Tyrol and Vorarlberg, but also the first administrator of the province of Salzburg, which became part of Austria in 1806, and governor of Venetia after he took power in 1815. Opposite, a monument commemorates the historian Ludwig Friedrich August von Pastor (1854 - 1928). Known as a historian of the popes, the conservative diplomat took an active part in Pope Pius X's fight against modernism. In 1908, he was elevated to the rank of baron by Emperor Franz Josef. Pastorstrasse, where the basilica is located, was dedicated to him.

The interior of the basilica is one of the most magnificent of its time. The Baroque splendour is dazzling in brilliant white and decorated with countless paintings and columns. The Augsburg academy director Matthäus Günther designed the ceiling painting, which depicts an apocalyptic Madonna and Judith, who proudly presents the beholder with the severed head of Holofernes, in true Baroque style. The Gothic Madonna with an aureole above the monstrance was moved from the previous building, which was constructed around 1311. The main altar with its four columns symbolises the founding legend.

Wilten Abbey

The history of Wilten Abbey opposite also began with a legend. The giant Haymon is said to have founded a monastery on the ruins of the Roman fortress of Veldidena in the late 9th century. It is very likely that the Dukes of Bavaria had a monastery built in order to administratively integrate their territories in the Inn Valley into their domain. Thanks to their educated and literate brethren, ecclesiastical institutions such as monasteries were the most important administrative units in late antiquity for orchestrating structures, rule, laws, ownership, infrastructure and public order. In Wilten, a small community of pastors ran the affairs of the region between the Nordkette and Brenner. In 1128, Bishop Reginbert of Brixen handed over the monastery to the then newly founded Premonstratensian Order. The document confirming the takeover by the Premonstratensian Order in 1138 is still preserved in the archives of Wilten Abbey. Considering that the parent monastery in Premontre in France was only founded in 1120 by the founder of the order, Norbert of Xanten, the expansion to Tyrol was very rapid. Starting in France, the order managed to be represented throughout Europe within just a few decades. The idea of poverty was not as pronounced among the Premonstratensians as it was among the Franciscans or Dominicans, who emerged at the same time. Although Norbert, who was venerated as a saint from 1582, was a church reformer, he could not deny his origins in the nobility and his political role as Archbishop of Magdeburg and advisor to the king, despite his spirituality.

The assumption of ecclesiastical rights and duties was linked to the lordship over lands that the monastery could dispose of. In 1140, the Brixen Abbey transferred all of its land between Berg Isel, Sill and Inn to Wilten Abbey. The powerful Bavarian duke Heinrich der Löwe donated a hereditary farm from his estate to the monastery. The Mentlberg and lands in the Sellraintal valley were also added. Tyrol's perhaps most beautiful valley head, Lüsens, is still owned by the church today. The monastery had lower jurisdiction over these lands, which included everything that was not subject to the blood court. In 1180, it was Wilten Abbey that ceded the lands south of the Inn to the Counts of Andechs, on which the town was founded. Part of the deal was the takeover of several parishes by the Premonstratensians.

With the blessing of God and the industrious labour of the subjects, abbots were regarded as strict landlords, the monastery grew, even if there were repeated setbacks, such as the fire in 1304. A Romanesque church was built in 1311, as was the foundation of the monastery. A monastery school was mentioned in 1313. Ruedger the schoolmaster found his way into the chronicles of Wilten as village master even 10 years earlier. In addition to lively panel painting, the pupils probably also copied books. In the still existing Leuthaus not only secular guests of the monastery who could not be accommodated inside were received here. The basic structure of the building, which dates back to Roman times, served as the official residence of the Wilten court judge. In 1818, the district court moved from Sonnenburg Castle to the Leuthaus. The mighty building, which is well worth seeing, unfortunately disappears visually next to the monastery, the street and the surrounding blocks of flats. Today it houses the Wilten Boys' Choir.

The Baroque era's frenzy of remodelling did not stop at the monastery. The fashion of the time demanded an architectural statement in the 17th century in order to represent the pastoral duties of the Praemonstratensians in a manner befitting their rank. The baroque rebuilding of the monastery in 1665 was a matter of imperial importance. Emperor Leopold I was personally present at the opening. The lavish church furnishings and many of the paintings were added to over the following centuries. The gleaming white stone figures on the gable depict the patron saints Laurentius and Stefanus as well as St Mary. The entrance gate is guarded by the giants Haymon and Thyrsus, the two legendary protagonists of the legend surrounding the foundation of the monastery. Inside, frescoes depict the handover of the monastery to St Norbert, the stoning of St Stephen and St Anne, the patron saint of Wilten, who protects the monastery from approaching Bavarian troops. Directly behind the mighty entrance portal stands a man-sized figure of Haymon in silver armour with a dragon's tongue in his hand. The black side altars and the main altar are particularly splendid in contrast to the rest of the church's white colour scheme. Parts such as the chapter house and the cross vault have been preserved and date back to the time of the Gothic predecessor building.

The abbots of Wilten were represented in the provincial parliament until 1914. Even in the First Republic and during the time of Dollfuß and Schuschnigg, the abbey played a role in politics as Innsbruck's most important Catholic institution. The Christian Social Party relied on the influence of the church's pulpits, infrastructure, front organisations and press organs. In 1939, Wilten Monastery was dissolved by the National Socialists and all associated associations and organisations were incorporated into the party structure. During an air raid in 1944, large parts of the monastery were devastatingly damaged. The reopening after successful renovation was celebrated at Christmas 1952.

Today, Wilten Abbey looks after 22 parishes in and around Innsbruck. The Premonstratensians are one of the most influential orders in the city. After the First World War, youth centres for pastoral care were founded in Pradl, Hötting and Wilten to support single mothers and working-class families. Above Mentlberg Castle, on the grounds of the monastery, the Waldhüttl for the Vincentian community, where migrants provide for themselves and run an open church. The monastery is still a centre of art and culture today. Particular pride is taken in the Wilten Boys' Choirwhich were first mentioned in 1235. The collections, archives and library of Wilten Abbey can be visited as part of a guided tour. Concerts are regularly held on the premises of the monastery. The sumptuous interior furnishings are also very impressive. In the collegiate church there is a collection of icons with works dating back to the 13th century, which show the similarities and differences between the Catholic and Orthodox faiths. In the area of the monastery gate you can see Klosterladele buy small local delicacies and gifts.

Innsbruck as part of the Imperium Romanum

Of course, the Inn Valley was not first colonised with the Roman conquest. The inhabitants of the Alps, described as wild, predatory and barbaric, were labelled by Greek and Roman writers with the rather vague collective term „Raeter“ dubbed. These people probably did not refer to themselves as such. Today, researchers use the term Raeter to refer to the inhabitants of Tyrol, the lower Engadin and Trentino, the area of the Fritzens-Sanzeno Culturenamed after their major archaeological sites. Two-storey houses with stone foundations grouped in clustered villages, similar language idioms, burnt offering sites such as the Goldbühel in Igls and pottery finds indicate a common cultural background and economic exchange between the ethnic groups and organisations between Vorarlberg, Lake Garda and Istria. According to finds, there was also a lively exchange with other ethnic groups such as the Celts in the west or the Etruscans in the south even before the Roman conquests. Etruscan characters were used for all kinds of records.

According to Roman interpretation, the Breons, a tribe within the Raetians, lived in the area of today's Innsbruck. This name persisted even after the fall of the Roman Empire until the Bavarian colonisation in the 9th century. Although there were no Breon Popular Frontthe quote from Life of Brian could also have been used in pre-Christian Innsbruck:

"Apart from medicine, sanitation, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, water treatment and public health insurance, what, I ask you, have the Romans ever done for us?"

A climatic phenomenon known as Roman climate optimum the area north of the Alps for the first time in history. Roman Empire interesting and accessible via the Alpine crossings. From a strategic point of view, the conquest was overdue anyway. The Roman troops in Gaul in the west and Illyria on the Adriatic in the east were to be connected, invasions by barbarian peoples into northern Italian settlements were to be prevented and routes for trade, travellers and the military were to be expanded and secured. The Inn Valley, an important corridor for troop movements, communication and trade on the outer edge of the Roman economic area, had to be brought under Roman control. The transport route between today's Seefeld Saddle and the Brenner Pass already existed before the Roman conquest, but was not a paved, modern road that met the demands of Roman requirements.

In the year 15 BC, the generals Tiberius and Drusus, both stepsons of Emperor Augustus, conquered the area that is now Innsbruck. Drusus marched from Verona to Trento and then along the Adige River over the Brenner Pass to the area that is now Innsbruck. There, the Roman troops fought against the local Breons. The Roman administration was rolled out under Augustus' successor Tiberius. The military was followed by the administration. Today's Tyrol was divided at the river Ziller. The area east of the Ziller became part of the province of Noricum, Innsbruck hingegen wurde ein Teil der Provinz Raetia et Vindelicia. It stretched from today's central Switzerland with the Gotthard massif in the west to the Alpine foothills north of Lake Constance, the Brenner in the south and the Ziller in the east. The Ziller has remained a border in the division of Tyrol in terms of church law to this day. The area east of the Ziller belongs to the diocese of Salzburg, while Tyrol west of the Ziller belongs to the diocese of Innsbruck.

It is unclear whether the Romans destroyed the settlements and places of worship between Zirl and Wattens during their campaign of conquest. The burnt offering site at Goldbühel in Igls was no longer used after the year 15. There are also no precise sources on the treatment of the conquered people. The settlements of the Breon population were located on the higher scree cones such as Amras and Wilten and above the Inn Valley, which was a marshy area. The Romans settled in the area of today's Wilten Abbey. The Roman troops most likely drew on the expertise of the local population to secure and construct the transport routes. Today we would probably say that important human resources were handled with care after the takeover.

The soon Via Raetia named road made the Via Claudia Augustawhich linked Italy and Bavaria via the Reschen Pass and Fern Pass, as the most important transport route across the Alps. In the 3rd century after the turn of the millennium, the Brenner route became the via publica developed. It was too steep in parts for poorly equipped trade trains to become the main route, but traffic increased noticeably and with it the importance of the Wipp and Inn valleys. Just over five metres wide, it ran from the Brenner Pass to the Ferrariwiese meadow above Wilten over the Isel mountain to today's Gasthaus Haymon. At intervals of 20 to 40 kilometres there were rest stations with accommodation, restaurants and stables. In Sterzing, on the Brenner Pass, in Matrei and Innsbruck, these Roman Mansiones Villages where Roman culture began to establish itself.

The settlement and later the military camp were connected via this road network. Castell Veldidena was integrated into an economic and intellectual area stretching from Great Britain to the Baltic and North Africa. The population began to adapt to the conditions as a transit and supply station. Blacksmiths were the first steps in an early metalworking industry and inns were also founded. The Romans brought many of their cultural achievements such as imperial coinage, glass and brick production, the Latin language, bathhouses, thermal baths, schools and wine across the Brenner Pass. Roman law and administration were also introduced. Military service in the Roman army enabled people to climb the social ladder. With an imperial decree in 212, the Breton subjects became full Roman citizens with all the associated rights and duties. After Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century, the Tyrolean region was also proselytised. The episcopal administration was based in Brixen in South Tyrol and Trento.

There is hardly anything left of Roman Innsbruck in the cityscape. Exhibits can be admired in the Tyrolean State Museum Ferdinandeum. In various excavation projects, burial sites and remains such as walls, coins, bricks and everyday objects from the Roman period in Innsbruck were found around today's Wilten Abbey. The centre of the Leuthauses next to the monastery dates back to Roman times. One of the Roman milestones of the former main road over the Brenner Pass can be seen in Wiesengasse near the Tivoli Stadium.

Thyrsus, Haymon and the Bavarians

After the disappearance of the Western Roman Empire and its associated administration, Germanic tribes took control of the area that is now Innsbruck. Between the turn of time and the coronation of Charlemagne in the year 800, the period known as the Migration Period, Late Antiquity or the Early Middle Ages, a whole range of peoples were to be found in what is now North Tyrol. Breons, Romans, Goths, Lombards, Bavarians, Suevians and Slavs settled next to and behind each other in various areas north of the Brenner Pass. The Bavarians were able to assert themselves as a regional power in the central Inn Valley. During the land conquest, the Castell Veldidena The transition to Bavarian rule was less sudden and warlike for the Breton-Romanised population, however, and much more fluid. They were not barbarian destroyers, but groups that had been in contact with the Roman world in one form or another for centuries. Fighting was probably the exception. Cultures gradually intermingled at a time when the structure of power was rather loose. The everyday language of the people was a form of Germanic, but Latin had also established itself early on as a written language among the "barbarians" north of the Alps.

However, the most important remnant of the Romans was Christianity. The Bavarians were Christianised from the 8th century at the latest. At the time of Charlemagne (approx. 748 - 814), the Dukes of Bavaria and with them the Inn Valley became part of the Heiligen Römischen Reicheswhich extended over large parts of central Europe and northern Italy. The rulers relied on the ecclesiastical structures of the Romans to administer the territory, as clerics were often the only scribes. Instead of Roman emperors, an arrogant aristocracy ruled in the name of God over their subjects, who were agricultural labourers, as feudatories of Charles, King of the Franks, anointed by the Pope. The Christian church father Paul wrote in his Letter to the Romans laid the theological foundation for this system:

Jedermann sei untertan der Obrigkeit, die Gewalt über ihn hat. Denn es ist keine Obrigkeit außer von Gott; wo aber Obrigkeit ist, ist sie von Gott angeordnet. Darum: Wer sich der Obrigkeit widersetzt, der widerstrebt Gottes Anordnung; die ihr aber widerstreben, werden ihr Urteil empfangen. Denn die Gewalt haben, muss man nicht fürchten wegen guter, sondern wegen böser Werke. Willst du dich aber nicht fürchten vor der Obrigkeit, so tue Gutes, dann wirst du Lob von ihr erhalten. Denn sie ist Gottes Dienerin, dir zugut. Tust du aber Böses, so fürchte dich; denn sie trägt das Schwert nicht umsonst. Sie ist Gottes Dienerin und vollzieht die Strafe an dem, der Böses tut. Darum ist es notwendig, sich unterzuordnen, nicht allein um der Strafe, sondern auch um des Gewissens willen. Deshalb zahlt ihr ja auch Steuer; denn sie sind Gottes Diener, auf diesen Dienst beständig bedacht.

Culturally, Christianity also proved to be adaptable to traditions and customs in the Alpine region. The martyrs and saints of Christianity replaced the pagan polytheism. Old festivals such as the winter solstice, Thanksgiving and the beginning of spring were integrated into the Christian calendar and replaced by Christmas, All Saints' Day and Easter. Popular legends about miraculous plants, ominous mountain peaks, magical beings such as the Saligen Fräuleinenchanted kings and other legendary figures could easily be worshipped alongside Christianity.

Two of the most popular of these in Innsbruck to this day play the leading role in the founding myth of Wilten Abbey. An extraordinarily strong knight, known as the giant Haymon, travelled to Tyrol sometime between late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. In Tyrol he met the long-established giant Thyrsus von Seefeld. While the Germanic knight Haymon was armed with a sword and shield, Thyrsus, who had a Romanised name but was actually a wild inhabitant of the Alps, only had a tree trunk at his disposal. As it happened, the modern sword struck the wooden club and Haymon killed Thyrsus. In remorse for his deed, he converted to Christianity and was baptised by the Bishop of Chur. Instead of building a castle in the Inn Valley as planned, he built a monastery on the ruins of the Roman fortress of Veldidena. However, a terrifying dragon dwelled in the nearby Sill Gorge, which not only ravaged the new building of the now Christian hero every night, but also made it impossible to settle the area in any meaningful way. Haymon killed the beast, cut off its tongue and bequeathed it to his own foundation. After his career as a dragon slayer, Haymon handed over the monastery to the Benedictine monks of Tegernsee and joined the brotherhood himself as a lay brother. The people of the region were so grateful to the giant for freeing them from the dragon that they gladly placed themselves in the dutiful care of Wilten Abbey in order to cultivate the once wild land as farmers.

In this parable, Haymon stands for the initially violent but later noble and benevolent Germanic colonisers, Thyrsus for the brave and wild but ultimately defeated inhabitants of the region between the Seefeld plateau and the Brenner Pass. The dragon symbolises the evil, destructive and unchristian paganism that is eradicated by the converted Teutons. The monastery brothers, richly endowed by the brave knight, are the organising hand without which nothing would work.

The Haymonsage and their morals were just as flexible over the centuries, depending on the zeitgeist, as Christianity was when it was introduced in late antiquity. One time Haymon was a nobleman from the Rhine who came to Tyrol after the death of Charlemagne, another time he travelled between Ravenna and Germany as a follower of the Ostrogothic king Theoderic, better known as Dietrich of Bern. From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, the conversion HaymonsThe protection of peasant subjects by Christian chivalry and the founding of monasteries took centre stage in order to underpin the beneficial feudal system. In an article in the Innsbrucker Nachrichten of 2 October, on the other hand, the author Dr Franz Wöß left the Catholic element of the monastery building almost completely aside and emphasised the heroic German before turning to the healing properties of thyrsus oil, which the Seefeld farmers had been extracting from the oily slate stones since the Middle Ages. In this version of the legend, Haymon retired to the wilderness in Seefeld as a hermit after his heroic deeds instead of ending his life as a cleric in Wilten Abbey. After the Second World War, however, people wanted to distance themselves as far as possible from Germanism. The 1956 inscription on the façade of the "Inn Zum Riesen Haymon" shows the defeated Thyrsus with an Austrian coat of arms, in keeping with the victim myth of the post-war period.

Article: The Giant Haymon

Published: Neue Tiroler Stimmen / 15 April 1875

(The giant Haymon), who - 13 feet tall and weighing 7 hundredweights - had been standing in front of the collegiate church in Wilten for about 150 years, like his opponent Thyrſus (of Seefeld).

had been standing in a niche in the wall, but accidentally suffered a fall due to a gust of wind on the 20th of March, early at 7 o'clock, so that it was smashed into many pieces, has now been put back together again by skilful hands, and the day before yesterday was raised safely to its old position by means of a pulley. Of course, it was secured against similar misfortune in present and future stormy times! May he henceforth keep faithful vigil over the - before

The church of St Laurentius, founded 1000 years ago, and the canons' monastery responsible for it - under God's gracious care!

The Counts of Andechs and the foundation of Innsbruck

The 12th century brought an economic, scientific and social boom to Europe and is regarded as a kind of early medieval renaissance. Via the Crusades, there was an increased exchange with the cultures of the Middle East, which were more developed in many respects. Arab scholars brought translations of Greek thinkers such as Aristotle to Europe via southern Spain and Italy. Roman law was rediscovered at the first universities south of the Alps. New agricultural knowledge and a favourable climate, which was to last until the middle of the 14th century, made it possible for towns and larger settlements to emerge. One of these settlements was located to the north of Wilten Abbey between the River Inn and the Nordkette mountain range.

Politically and economically, the importance of the Inn Valley and the area north of it was mainly limited to transit. Tyrol had two low Alpine crossings, the Reschen Pass and the Brenner Pass, which were important for the imperial connection between the German lands in the north and the lands in Italy. In 1024, the Salian Conrad II, a rival of the Bavarian dukes from the House of Wittelsbach, was elected king. In order to bring these two Alpine crossings away from his Bavarian rivals and under the control of the Imperial Church, which was loyal to him, Conrad II granted the territory of Tyrol as a fief to the bishops of Brixen and Trento in 1027. The bishops in turn needed so-called bailiffs to administer these lands and administer justice.

These bailiffs of the Bishop of Brixen were the Counts of Andechs. The Andechs family may be overshadowed today by the Guelphs, Hohenstaufen, Wittelsbach and Habsburg dynasties, but they were an influential family in the High Middle Ages. They came from the area around Lake Ammer in Bavaria and owned estates in Upper Bavaria between the Lech and Isar rivers and east of Munich. Through skilful marriage politics, they had acquired the titles of Dukes of Merania, a region on the Dalmatian coast, and Margraves of Istria. They thus rose in rank within the Heiligen Römischen Reiches on. In the 12th century, they founded the Dießen monastery and the monastery on the holy mountain of Andechs above Lake Ammersee to ensure both administration and later salvation. In 1165, Otto V of Andechs came to the bishop's see in Brixen and gave the bailiwick over this high monastery to his brother. From then on, they administered the central part of the Inn Valley, the Wipp Valley, the Puster Valley and the Eisack Valley.

Today, Innsbruck stretches along both sides of the Inn. In the 12th century, this area was under the influence of two lords of the manor. South of the Inn, Wilten Abbey exercised lordship. The area north of the river was under the administration of the Andechs. While the southern urban area around the monastery had been used for agriculture for centuries, the alluvial area of the unregulated watercourse could not be cultivated before the High Middle Ages and was sparsely populated. The Inn Valley was densely forested and the banks of the wide Inn were swampy. Most of the people worked in agriculture, which was run by their landlord. They lived in poor huts made of mud and wood. There was hardly any medical care outside the towns, infant mortality was high and hardly anyone lived past the age of 50. Around the year 1133, the Andechs founded the market in what is now St Nicholas' Square Anbruggen and connected the northern and southern banks of the Inn via a bridge. The construction of the bridge turned the unusable agricultural land at the foot of the Nordkette mountain range into a trading centre. It greatly facilitated the movement of goods in the Eastern Alps. The Brenner route had become more interesting thanks to one of the innovations of the medieval Renaissance: new harnesses made it possible to negotiate the steep climbs with carts. The shorter Via Raetia had the Via Claudia Augusta over the Reschen Pass as the main transport route across the Alps. The customs revenue generated from trade between the German and Italian towns allowed the settlement to prosper. Blacksmiths, innkeepers, carriage operators, tailors, carpenters, rope makers, wagon makers and tanners settled in the small market. Horses, traders and carters had to be looked after and accommodated, and carts had to be repaired. The larger of these businesses employed clerks and farm labourers. The transformation from pure agriculture to a town began.

Anbruggen grew rapidly, but the space between the Nordkette and the Inn was limited. In 1180, Berchtold V of Andechs acquired a piece of land on the south side of the Inn from Wilten Monastery. This was the definitive starting signal for the genesis of Innsbruck. The abbot did not want to take his foot out of the door completely, as the new settlement developed splendidly thanks to the customs revenue. The document mentions three houses that were reserved for Wilten Abbey within the new settlement. In the course of building the town wall, the Counts of Andechs had the Andechs Castle and moved their ancestral seat from Merano to Innsbruck. Sometime between 1187 and 1204, the citizens of Innsbruck were granted city rights. The official date of foundation is often taken as 1239, when the last count of the Andechs dynasty, Otto VIII, formally confirmed the city charter in a document. Innsbruck was already the mint of the Andechs at this time and would probably have become the capital of their principality. But things turned out differently. In 1246, the Bavarian Wittelsbach dynasty, the Andechs' biggest rivals in southern Germany, destroyed their ancestral castle on Lake Ammersee. Otto, the last count of the House of Andechs-Merania, died without descendants in 1248. 12 years earlier, he had married Elisabeth, the daughter of Count Albert VIII of Tyrol. This noble family with its ancestral castle in Merano thus took over the fiefs and parts of the possessions, including the town on the Inn, as well as the arch-enemy with the Bavarian Wittelsbachs.

Believe, Church and Power

Die Fülle an Kirchen, Kapellen, Kruzifixen und Wandmalereien im öffentlichen Raum wirkt auf viele Besucher Innsbrucks aus anderen Ländern eigenartig. Nicht nur Gotteshäuser, auch viele Privathäuser sind mit Darstellungen der Heiligen Familie oder biblischen Szenen geschmückt. Der christliche Glaube und seine Institutionen waren in ganz Europa über Jahrhunderte alltagsbestimmend. Innsbruck als Residenzstadt der streng katholischen Habsburger und Hauptstadt des selbsternannten Heiligen Landes Tirol wurde bei der Ausstattung mit kirchlichen Bauwerkern besonders beglückt. Allein die Dimension der Kirchen umgelegt auf die Verhältnisse vergangener Zeiten sind gigantisch. Die Stadt mit ihren knapp 5000 Einwohnern besaß im 16. Jahrhundert mehrere Kirchen, die in Pracht und Größe jedes andere Gebäude überstrahlte, auch die Paläste der Aristokratie. Das Kloster Wilten war ein Riesenkomplex inmitten eines kleinen Bauerndorfes, das sich darum gruppierte. Die räumlichen Ausmaße der Gotteshäuser spiegelt die Bedeutung im politischen und sozialen Gefüge wider.

Die Kirche war für viele Innsbrucker nicht nur moralische Instanz, sondern auch weltlicher Grundherr. Der Bischof von Brixen war formal hierarchisch dem Landesfürsten gleichgestellt. Die Bauern arbeiteten auf den Landgütern des Bischofs wie sie auf den Landgütern eines weltlichen Fürsten für diesen arbeiteten. Damit hatte sie die Steuer- und Rechtshoheit über viele Menschen. Die kirchlichen Grundbesitzer galten dabei nicht als weniger streng, sondern sogar als besonders fordernd gegenüber ihren Untertanen. Gleichzeitig war es auch in Innsbruck der Klerus, der sich in großen Teilen um das Sozialwesen, Krankenpflege, Armen- und Waisenversorgung, Speisungen und Bildung sorgte. Der Einfluss der Kirche reichte in die materielle Welt ähnlich wie es heute der Staat mit Finanzamt, Polizei, Schulwesen und Arbeitsamt tut. Was uns heute Demokratie, Parlament und Marktwirtschaft sind, waren den Menschen vergangener Jahrhunderte Bibel und Pfarrer: Eine Realität, die die Ordnung aufrecht hält. Zu glauben, alle Kirchenmänner wären zynische Machtmenschen gewesen, die ihre ungebildeten Untertanen ausnützten, ist nicht richtig. Der Großteil sowohl des Klerus wie auch der Adeligen war fromm und gottergeben, wenn auch auf eine aus heutiger Sicht nur schwer verständliche Art und Weise. Verletzungen der Religion und Sitten wurden in der späten Neuzeit vor weltlichen Gerichten verhandelt und streng geahndet. Die Anklage bei Verfehlungen lautete Häresie, worunter eine Vielzahl an Vergehen zusammengefasst wurde. Sodomie, also jede sexuelle Handlung, die nicht der Fortpflanzung diente, Zauberei, Hexerei, Gotteslästerung – kurz jede Abwendung vom rechten Gottesglauben, konnte mit Verbrennung geahndet werden. Das Verbrennen sollte die Verurteilten gleichzeitig reinigen und sie samt ihrem sündigen Treiben endgültig vernichten, um das Böse aus der Gemeinschaft zu tilgen. Bis in die Angelegenheiten des täglichen Lebens regelte die Kirche lange Zeit das alltägliche Sozialgefüge der Menschen. Kirchenglocken bestimmten den Zeitplan der Menschen. Ihr Klang rief zur Arbeit, zum Gottesdienst oder informierte als Totengeläut über das Dahinscheiden eines Mitglieds der Gemeinde. Menschen konnten einzelne Glockenklänge und ihre Bedeutung voneinander unterscheiden. Sonn- und Feiertage strukturierten die Zeit. Fastentage regelten den Speiseplan. Familienleben, Sexualität und individuelles Verhalten hatten sich an den von der Kirche vorgegebenen Moral zu orientieren. Das Seelenheil im nächsten Leben war für viele Menschen wichtiger als das Lebensglück auf Erden, war dies doch ohnehin vom determinierten Zeitgeschehen und göttlichen Willen vorherbestimmt. Fegefeuer, letztes Gericht und Höllenqualen waren Realität und verschreckten und disziplinierten auch Erwachsene.

Während das Innsbrucker Bürgertum von den Ideen der Aufklärung nach den Napoleonischen Kriegen zumindest sanft wachgeküsst wurde, blieb der Großteil der Menschen weiterhin der Mischung aus konservativem Katholizismus und abergläubischer Volksfrömmigkeit verbunden. Religiosität war nicht unbedingt eine Frage von Herkunft und Stand, wie die gesellschaftlichen, medialen und politischen Auseinandersetzungen entlang der Bruchlinie zwischen Liberalen und Konservativ immer wieder aufzeigten. Seit der Dezemberverfassung von 1867 war die freie Religionsausübung zwar gesetzlich verankert, Staat und Religion blieben aber eng verknüpft. Die Wahrmund-Affäre, die sich im frühen 20. Jahrhundert ausgehend von der Universität Innsbruck über die gesamte K.u.K. Monarchie ausbreitete, war nur eines von vielen Beispielen für den Einfluss, den die Kirche bis in die 1970er Jahre hin ausübte. Kurz vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg nahm diese politische Krise, die die gesamte Monarchie erfassen sollte in Innsbruck ihren Anfang. Ludwig Wahrmund (1861 – 1932) war Ordinarius für Kirchenrecht an der Juridischen Fakultät der Universität Innsbruck. Wahrmund, vom Tiroler Landeshauptmann eigentlich dafür ausgewählt, um den Katholizismus an der als zu liberal eingestuften Innsbrucker Universität zu stärken, war Anhänger einer aufgeklärten Theologie. Im Gegensatz zu den konservativen Vertretern in Klerus und Politik sahen Reformkatholiken den Papst nur als spirituelles Oberhaupt, nicht aber als weltlich Instanz, an. Studenten sollten nach Wahrmunds Auffassung die Lücke und die Gegensätze zwischen Kirche und moderner Welt verringern, anstatt sie einzuzementieren. Seit 1848 hatten sich die Gräben zwischen liberal-nationalen, sozialistischen, konservativen und reformorientiert-katholischen Interessensgruppen und Parteien vertieft. Eine der heftigsten Bruchlinien verlief durch das Bildungs- und Hochschulwesen entlang der Frage, wie sich das übernatürliche Gebaren und die Ansichten der Kirche, die noch immer maßgeblich die Universitäten besetzten, mit der modernen Wissenschaft vereinbaren ließen. Liberale und katholische Studenten verachteten sich gegenseitig und krachten immer aneinander. Bis 1906 war Wahrmund Teil der Leo-Gesellschaft, die die Förderung der Wissenschaft auf katholischer Basis zum Ziel hatte, bevor er zum Obmann der Innsbrucker Ortsgruppe des Vereins Freie Schule wurde, der für eine komplette Entklerikalisierung des gesamten Bildungswesens eintrat. Vom Reformkatholiken wurde er zu einem Verfechter der kompletten Trennung von Kirche und Staat. Seine Vorlesungen erregten immer wieder die Aufmerksamkeit der Obrigkeit. Angeheizt von den Medien fand der Kulturkampf zwischen liberalen Deutschnationalisten, Konservativen, Christlichsozialen und Sozialdemokraten in der Person Ludwig Wahrmunds eine ideale Projektionsfläche. Was folgte waren Ausschreitungen, Streiks, Schlägereien zwischen Studentenverbindungen verschiedener Couleur und Ausrichtung und gegenseitige Diffamierungen unter Politikern. Die Los-von-Rom Bewegung des Deutschradikalen Georg Ritter von Schönerer (1842 – 1921) krachte auf der Bühne der Universität Innsbruck auf den politischen Katholizismus der Christlichsozialen. Die deutschnationalen Akademiker erhielten Unterstützung von den ebenfalls antiklerikalen Sozialdemokraten sowie von Bürgermeister Greil, auf konservativer Seite sprang die Tiroler Landesregierung ein. Die Wahrmund Affäre schaffte es als Kulturkampfdebatte bis in den Reichsrat. Für Christlichsoziale war es ein „Kampf des freissinnigen Judentums gegen das Christentum“ in dem sich „Zionisten, deutsche Kulturkämpfer, tschechische und ruthenische Radikale“ in einer „internationalen Koalition“ als „freisinniger Ring des jüdischen Radikalismus und des radikalen Slawentums“ präsentierten. Wahrmund hingegen bezeichnete in der allgemein aufgeheizten Stimmung katholische Studenten als „Verräter und Parasiten“. Als Wahrmund 1908 eine seiner Reden, in der er Gott, die christliche Moral und die katholische Heiligenverehrung anzweifelte, in Druck bringen ließ, erhielt er eine Anzeige wegen Gotteslästerung. Nach weiteren teils gewalttätigen Versammlungen sowohl auf konservativer und antiklerikaler Seite, studentischen Ausschreitungen und Streiks musste kurzzeitig sogar der Unibetrieb eingestellt werden. Wahrmund wurde zuerst beurlaubt, später an die deutsche Universität Prag versetzt.

Auch in der Ersten Republik war die Verbindung zwischen Kirche und Staat stark. Der christlichsoziale, als Eiserner Prälat in die Geschichte eingegangen Ignaz Seipel schaffte es in den 1920er Jahren bis ins höchste Amt des Staates. Bundeskanzler Engelbert Dollfuß sah seinen Ständestaat als Konstrukt auf katholischer Basis als Bollwerk gegen den Sozialismus. Auch nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg waren Kirche und Politik in Person von Bischof Rusch und Kanzler Wallnöfer ein Gespann. Erst dann begann eine ernsthafte Trennung. Glaube und Kirche haben noch immer ihren fixen Platz im Alltag der Innsbrucker, wenn auch oft unbemerkt. Die Kirchenaustritte der letzten Jahrzehnte haben der offiziellen Mitgliederzahl zwar eine Delle versetzt und Freizeitevents werden besser besucht als Sonntagsmessen. Die römisch-katholische Kirche besitzt aber noch immer viel Grund in und rund um Innsbruck, auch außerhalb der Mauern der jeweiligen Klöster und Ausbildungsstätten. Etliche Schulen in und rund um Innsbruck stehen ebenfalls unter dem Einfluss konservativer Kräfte und der Kirche. Und wer immer einen freien Feiertag genießt, ein Osterei ans andere peckt oder eine Kerze am Christbaum anzündet, muss nicht Christ sein, um als Tradition getarnt im Namen Jesu zu handeln.

Big City Life in early Innsbruck

Innsbruck hatte sich von einem römischen Castell während des Mittelalters zu einer Stadt entwickelt. Diese formale Anerkennung Innsbrucks als Stadt durch den Landesfürsten brachte ein gänzlich neues System für die Bürger mit sich. Marktrecht, Baurecht, Zollrecht und eine eigene Gerichtsbarkeit gingen nach und nach auf die Stadt über. Stadtbürger unterlagen nicht mehr ihrem Grundherrn, sondern der städtischen Gerichtsbarkeit, zumindest innerhalb der Stadtmauern. Das geflügelte Wort "Stadtluft macht frei" rührt daher, dass man nach einem Jahr in der Stadt von allen Verbindlichkeiten seines ehemaligen Grundherrn frei war. Bürger konnten anders als unfreie Bauern und Dienstleute frei über ihren Besitz und ihre Lebensführung verfügen. Natürlich hatten sie Rechte und Pflichten zu erfüllen. Bürger lieferten zwar keinen Zehent ab, sondern bezahlten Steuern an die Stadt. Welche Gruppe innerhalb der Stadt welche Steuer zu bezahlen hatte, konnte die Stadtregierung selbst festlegen. Die Stadt wiederum musste diese Steuern nicht direkt abliefern, sondern konnte nach Abzug einer fixen Abgabe an den Landesfürsten frei über ihr Budget verfügen. Zu den Ausgaben neben der Stadtverteidigung gehörte die Kranken- und Armenfürsorge. Notleidende Bürger konnten in der „Boiling kitchen“ Speisen beziehen, so sie das Bürgerrecht hatten. Besondere Beachtung schenkte die Stadtregierung ansteckenden Krankheiten wie der Pest, die in regelmäßigen Abständen die Einwohner marterte.

In return for their rights, every citizen had to take the oath of citizenship. This civic oath included the obligation to pay taxes and perform military service. In addition to defending the town, the citizens were also deployed outside the town. In 1406, a delegation together with mercenaries opposed an Appenzell army in defence of the Upper Inn Valley. From 1511, according to Emperor Maximilian's Landlibell, the town council was also obliged to provide a contingent of conscripts for the defence of the country. In addition to this, there were volunteers who Freifähnlein For example, during the Turkish siege of Vienna in 1529, Innsbruckers were among the city's defenders.

Im 15. Jahrhundert wurde der Platz eng im rasch wachsenden Innsbruck. Das Bürgerrecht wurde zu einem exklusiven Gut. Nur noch freien Untertanen aus ehelicher Geburt war es möglich, das Stadtrecht zu erlangen. Um Bürger zu werden, mussten entweder Hausbesitz oder Fähigkeiten in einem Handwerk nachgewiesen werden, an der die Zünfte der Stadt interessiert waren. Der Streit darum, wer ein „echter“ Innsbrucker ist, und wer nicht, hält sich bis heute. Dass Migration und Austausch mit anderen immer schon die Garantie für Wohlstand waren und Innsbruck zu der lebenswerten Stadt gemacht haben, die sie heute ist, wird dabei oft vergessen.

Due to these restrictions, Innsbruck had a completely different social composition to the neighbouring villages. Craftsmen, merchants, civil servants and servants of the court dominated the cityscape. Merchants were often travelling people, officials and court servants also came to Innsbruck for a short time as part of a prince's entourage and did not have citizenship. It was the craftsmen who exercised a large part of the political power within the citizenry. Unlike peasants, they belonged to the mobile classes in the Middle Ages and early modern period. After their apprenticeship, they went to the Walzbefore they took the master craftsman's examination and either returned home or settled in another city. Craftsmen not only transferred knowledge, they also spread cultural, social and political ideas. The craft guilds sometimes exercised their own jurisdiction alongside the municipal jurisdiction among their members. They were social structures within the city structure that had a great influence on politics. Wages, prices and social life were regulated by the guilds under the supervision of the sovereign. One could speak of an early social partnership, as the guilds also provided social security for their members in the event of illness or occupational disability. Individual trades such as locksmiths, tanners, platers, carpenters, bakers, butchers and blacksmiths each had their own guild, headed by a master craftsman.

From the 14th century, Innsbruck demonstrably had a city council, the so-called Gemainand a mayor who was elected annually by the citizens. These were not secret but public elections, which were held every year around Christmas time. In the Innsbrucker Geschichtsalmanach von 1948 findet man Aufzeichnungen über die Wahl des Jahres 1598.

The Feast of St. Erhard, i.e., January 8th, played a significant role in the lives of the citizens of Innsbruck each year. On this day, they gathered to elect the city officials, namely the mayor, city judge, public orator, and the twelve-member council. A detailed account of the election process between 1598 and 1607 is provided by a protocol preserved in the city archive: "... The ringing of the great bell summoned the council and the citizenry to the town hall, and once the honorable council and the entire community were assembled at the town hall, the honorable council first convened in the council chamber and heard the farewell of the outgoing mayor of the previous year, Augustin Tauscher."

Der Bürgermeister vertrat die Stadt gegenüber den anderen Ständen und dem Landesfürsten, der die Oberherrschaft über die Stadt je nach Epoche mal mehr, mal weniger intensiv ausübte. Jeder Stadtrat hatte eigene, klar zugeteilte Aufgaben zu erfüllen wie die Überwachung des Marktrechts, die Betreuung des Spitals und der Armenfürsorge oder die für Innsbruck besonders wichtige Zollordnung. Der Konsum von Alkohol und das Verweilen in den Gaststätten war zu verschiedenen Zeiten unterschiedlich geregelt. Ärmeren Bevölkerungsschichten war es nicht nur zu teuer, sie durften auch nur zu gewissen Zeiten in die Gasthäuser. So sollte übermäßiger Trunkenheit und dem Anbetteln der Oberschicht vorgebeugt werden. Der Stadtrat kontrollierte die Qualität und Güte der Speisen ähnlich einem frühen Marktamt, waren Städte doch an der Qualität ihrer Betriebe interessiert, um als Wirtschaftsstandort und für Gäste interessant zu sein. Bei all diesen politischen Vorgängen sollte man sich stets in Erinnerung rufen, dass Innsbruck im 16. Jahrhundert etwa 5000 Einwohner hatte, von denen nur ein kleiner Teil das Bürgerrecht besaß. Besitzlose, fahrendes Volk, Erwerbslose, Dienstboten, Diplomaten, Angestellte, Frauen und Studenten waren keine wahlberechtigten Bürger. Zu wählen war ein Privileg der männlichen Oberschicht.

Contrary to popular belief, the Middle Ages were not a lawless time of arbitrariness. At both local and national level, there were codes that regulated very precisely what was permitted and what was forbidden. This could vary greatly depending on the ruler and the prevailing morals and customs. Carrying weapons, swearing, prostitution, making noise, playing music, blasphemy, children playing - anything and anyone could be targeted by the guardians of the law. If you include the rules for trade, customs duties, the exercise of professions by guilds and price fixing for all kinds of goods by the magistrate, pre-modern and early modern coexistence was no less regulated than it is today. The difference was control and enforcement power, which the authorities often lacked.

If someone was caught committing an unlawful or immoral act, there were courts that passed judgement. The medieval court days were held at the "Dingstätte" is held outdoors. The tradition of the Thing goes back to the old Germanic Thingwhere all free men gathered to dispense justice. The city council appointed a judge who was responsible for all offences that were not subject to the blood court. He was assisted by a panel of several jurors. Punishments ranged from fines to pillorying and imprisonment. The city also monitored compliance with religious order. "Heretics" and dissenters were not reprimanded by the church, but by the city government.

The penal system also included less humane methods than are common today, but torture was not used indiscriminately and arbitrarily. However, torture was also regulated as part of the procedure in particularly serious cases. Until the 17th century, suspects and criminals in Innsbruck were Kräuterturm at the south-east corner of the city wall, on what is now Herzog-Otto-Ufer. Both the trial and the serving of the sentence were public trials. The city tower was Fool's cottagea cage in which people were locked up and put on display. On the wooden Schandesel you were dragged through the town for minor offences. The pillory was located in the suburb, today's Maria-Theresien-Straße. There was no police force, but the town magistrate employed servants and town watchmen were posted at the town gates to keep the peace. It was a civic duty to help catch criminals. Vigilante justice was forbidden.

The responsibilities between municipal and manorial justice had been regulated in the Urbarbuch since 1288. The provincial court still had jurisdiction over serious offences. Crimes such as theft, murder and arson were subject to this blood law. The provincial court for all municipalities south of the Inn between Ampass and Götzens was located on the Sonnenburgwhich was located to the south above Innsbruck. In the 14th century, the Sonnenburg district court moved to the upper town square in front of the Innsbruck city tower, later to the town hall and in the early modern period to Götzens. With the centralisation of the law in the 18th century, the court moved to Götzens. Sonnenburg back to Innsbruck and was housed under different names and in different buildings such as the Leuthaus in Wilten, on the Innrain or at the Ettnau residence, known as the Malfatti Castlein the Höttinger Gasse.

From the late 15th century, Innsbruck's executioner was centralised and responsible for several courts and was based in Hall. The execution centres were located in several places over the years. For a long time, there was a gallows on a hill in today's Dreiheiligen district, right next to the main road. The Köpflplatz was located until 1731 at today's corner of Fallbachgasse / Weiherburggasse in Anpruggen. In Hötting stand der Galgen hinter der Kapelle zum Großen Gott. Die heutige Kapelle, die neben dem barocken Kruzifix Keramikfiguren des bekannten Künstlers Max Spielmann (1906 – 1984) trägt, wurde bei Straßenarbeiten in den 1960er Jahren versetzt. Während Spielmanns Denkmal Totentanz an die Gefallenen des Zweiten Weltkriegs erinnert, konnten zum Tode Verurteilte am letzten Weg hier ein letztes Gebet zum Himmel schicken, bevor ihnen der Strick um den Hals gelegt oder der Kopf abgeschlagen wurde, je nach gesellschaftlichem Status und Art des Verbrechens. Es war nicht unüblich, dass der Verurteilte seinem Henker eine Art Trinkgeld zusteckte, damit sich dieser bemühte, möglichst genau zu zielen, um so die Hinrichtung so schmerzlos wie möglich zu gestalten. Viel konnte schiefgehen. Traf das Schwert nicht genau, wurde die Schlinge nicht sorgfältig umgelegt oder riss gar das Seil, erhöhte sich das Leiden des Verurteilten. Für die Obrigkeit und öffentliche Ordnung besonders schädliche Delinquenten wie der „Ketzer“ Jakob Hutter oder die gefassten Anführer der Bauernaufstände von 1525 und 1526 wurden vor dem Goldenen Dachl executed in a manner suitable for the public. "Embarrassing" punishments such as quartering or wheeling, from the Latin word poena were not the order of the day, but could be ordered in special cases. Executions were a demonstration of power by the authorities and were public. It was seen as a way of cleansing society of criminals and was intended to serve as a deterrent. Large crowds gathered to accompany the gallows bird on its final journey. Classes at the university were suspended on execution days to allow students to attend and purify them. The bodies of the executed were often left hanging and buried outside the consecrated area of the cemeteries or given to the university for study purposes. The last public execution in Austrian history took place in 1868. Even then, people were not squeamish, but the killings on the stranglehold, which was the method of choice for executions until the 1950s, were no longer a spectacle in front of an audience.

With the centralisation of law under Maria Theresa and Joseph II in the 18th century and the General Civil Code in the 19th century under Franz I, the law passed from cities and sovereigns to the monarch and their administrative bodies at various levels. Torture was abolished. The Enlightenment had fundamentally changed the concept of law, punishment and rehabilitation. The collection of taxes was also centralised, which resulted in a great loss of importance for the local nobility and an increase in the status of the civil service. With the increasing centralisation under Maria Theresa and Joseph II, taxes and customs duties were also gradually centralised and collected by the Imperial Court Chamber. As a result, Innsbruck, like many municipalities at the time, lost a large amount of revenue, which was only partially offset by equalisation.

The master builders Gumpp and the baroqueisation of Innsbruck

The works of the Gumpp family still strongly characterise the appearance of Innsbruck today. The baroque parts of the city in particular can be traced back to them. The founder of the dynasty in Tyrol, Christoph Gumpp (1600-1672), was actually a carpenter. However, his talent had chosen him for higher honours. The profession of architect or artist did not yet exist at that time; even Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci were considered craftsmen. After working on the Holy Trinity Church, the Swabian-born Gumpp followed in the footsteps of the Italian master builders who had set the tone under Ferdinand II. At the behest of Leopold V, Gumpp travelled to Italy to study theatre buildings and to learn from his contemporary style-setting colleagues his expertise for the planned royal palace. Comedihaus polish up.

His official work as court architect began in 1633. New times called for a new design, away from the Gothic-influenced architecture of the Middle Ages and the horrors of the Thirty Years' War. Over the following decades, Innsbruck underwent a complete renovation under the regency of Claudia de Medici. Gumpp passed on his title to the next two generations within the family. The Gumpps were not only active as master builders. They were also carpenters, painters, engravers and architects, which allowed them to create a wide range of works similar to the Tiroler Moderne around Franz Baumann and Clemens Holzmeister at the beginning of the 20th century to realise projects holistically. They were also involved as planners in the construction of the fortifications for national defence during the Thirty Years' War.

Christoph Gumpp's masterpiece, however, was the construction of the Comedihaus in the former ballroom. The oversized dimensions of the then trend-setting theatre, which was one of the first of its kind in Europe, not only allowed plays to be performed, but also water games with real ships and elaborate horse ballet performances. The Comedihaus was a total work of art in and of itself, which in its significance at the time can be compared to the festival theatre in Bayreuth in the 19th century or the Elbphilharmonie today.

His descendants Johann Martin Gumpp the Elder, Georg Anton Gumpp and Johann Martin Gumpp the Younger were responsible for many of the buildings that still characterise the townscape today. The Wilten collegiate church, the Mariahilfkirche, the Johanneskirche and the Spitalskirche were all designed by the Gumpps. In addition to designing churches and their work as court architects, they also made a name for themselves as planners of secular buildings. Many of Innsbruck's town houses and city palaces, such as the Taxispalais or the Altes Landhaus in Maria-Theresien-Straße, were designed by them. With the loss of the city's status as a royal seat, the magnificent large-scale commissions declined and with them the fame of the Gumpp family. Their former home is now home to the Munding confectionery in the historic city centre. In the Pradl district, Gumppstraße commemorates the Innsbruck dynasty of master builders.

Baroque: art movement and art of living

Anyone travelling in Austria will be familiar with the domes and onion domes of churches in villages and towns. This form of church tower originated during the Counter-Reformation and is a typical feature of the Baroque architectural style. They are also predominant in Innsbruck's cityscape. Innsbruck's most famous places of worship, such as the cathedral, St John's Church and the Jesuit Church, are in the Baroque style. Places of worship were meant to be magnificent and splendid, a symbol of the victory of true faith. Religiousness was reflected in art and culture: grand drama, pathos, suffering, splendour and glory combined to create the Baroque style, which had a lasting impact on the entire Catholic-oriented sphere of influence of the Habsburgs and their allies between Spain and Hungary.

The cityscape of Innsbruck changed enormously. The Gumpps and Johann Georg Fischer as master builders as well as Franz Altmutter's paintings have had a lasting impact on Innsbruck to this day. The Old Country House in the historic city centre, the New Country House in Maria-Theresien-Straße, the countless palazzi, paintings, figures - the Baroque was the style-defining element of the House of Habsburg in the 17th and 18th centuries and became an integral part of everyday life. The bourgeoisie did not want to be inferior to the nobles and princes and had their private houses built in the Baroque style. Pictures of saints, depictions of the Mother of God and the heart of Jesus adorned farmhouses.

Baroque was not just an architectural style, it was an attitude to life that began after the end of the Thirty Years' War. The Turkish threat from the east, which culminated in the two sieges of Vienna, determined the foreign policy of the empire, while the Reformation dominated domestic politics. Baroque culture was a central element of Catholicism and its political representation in public, the counter-model to Calvin's and Luther's brittle and austere approach to life. Holidays with a Christian background were introduced to brighten up people's everyday lives. Architecture, music and painting were rich, opulent and lavish. In theatres such as the Comedihaus dramas with a religious background were performed in Innsbruck. Stations of the cross with chapels and depictions of the crucified Jesus dotted the landscape. Popular piety in the form of pilgrimages and the veneration of the Virgin Mary and saints found its way into everyday church life. Multiple crises characterised people's everyday lives. In addition to war and famine, the plague broke out particularly frequently in the 17th century. The Baroque piety was also used to educate the subjects. Even though the sale of indulgences was no longer a common practice in the Catholic Church after the 16th century, there was still a lively concept of heaven and hell. Through a virtuous life, i.e. a life in accordance with Catholic values and good behaviour as a subject towards the divine order, one could come a big step closer to paradise. The so-called Christian edification literature was popular among the population after the school reformation of the 18th century and showed how life should be lived. The suffering of the crucified Christ for humanity was seen as a symbol of the hardship of the subjects on earth within the feudal system. People used votive images to ask for help in difficult times or to thank the Mother of God for dangers and illnesses they had overcome.

The historian Ernst Hanisch described the Baroque and the influence it had on the Austrian way of life as follows:

„Österreich entstand in seiner modernen Form als Kreuzzugsimperialismus gegen die Türken und im Inneren gegen die Reformatoren. Das brachte Bürokratie und Militär, im Äußeren aber Multiethnien. Staat und Kirche probierten den intimen Lebensbereich der Bürger zu kontrollieren. Jeder musste sich durch den Beichtstuhl reformieren, die Sexualität wurde eingeschränkt, die normengerechte Sexualität wurden erzwungen. Menschen wurden systematisch zum Heucheln angeleitet.“

The rituals and submissive behaviour towards the authorities left their mark on everyday culture, which still distinguishes Catholic countries such as Austria and Italy from Protestant regions such as Germany, England or Scandinavia. The Austrians' passion for academic titles has its origins in the Baroque hierarchies. The expression Baroque prince describes a particularly patriarchal and patronising politician who knows how to charm his audience with grand gestures. While political objectivity is valued in Germany, the style of Austrian politicians is theatrical, in keeping with the Austrian bon mot of "Schaumamal".

The Reformation in Tyrol

From today's perspective, the Reformation may have been a matter of faith. However, if we consider faith as an essential building block of everyday life and the identity of contemporaries, we realise that it was only one expression of many things that were in a state of upheaval. The religious reformation, which erupted in bloodshed between the 15th and 17th centuries, was a turning point for society as a whole, similar to 1848 or 1968. The majority of people may have remained superficially unaffected by it, but many things changed for everyone as a result of these revolutions. The accompanying social and political change did not stop at the Holy Land of Tyrol.

Around 1500, new discoveries and new ways of thinking began to herald the end of the Middle Ages. Artists, scholars and clerics throughout Europe began to question hierarchies, order and legitimisation. With the theological reformers of the 15th and 16th centuries, the feudal system, which saw the church and nobility above the people and bourgeoisie, began to crumble. In the 15th century, the Bohemian clergyman Jan Hus was one of the first in mainland Europe to question the omnipotence of the Pope and was banished to the stake at the Council of Constance for his actions. In France and Switzerland, it was Jean Calvin (1509 - 1564), in Holy Roman Empire Martin Luther (1483 - 1546) and Thomas Müntzer (1489 - 1525), who challenged the Roman Church in the 16th century.

In Tyrol, the mining towns of Hall and Schwaz were the main centres of the Reformation in the early 16th century. Many miners came from Saxony and brought their ideas about faith and the church with them. The old liturgy with sermons in incomprehensible Latin did not correspond to these ideas. Preachers such as Dr Jacob Strauß stirred up the people with Lutheran ideas, which also included criticism of the clergy and the ruling system.

This religious crisis also led to problems in the secular world outside the churches. Faith and the secular were not separate spheres. If the miners were dissatisfied with the pastoral care, they went on strike. Public order was in danger, and not just because the miners had the right to bear arms. They were well connected with each other. A general strike could trigger an economic crisis. The Fuggers and Habsburgs, capital and political power, were very careful not to let things get that far and granted the miners special rights.

Not only the miners, but also the progressive sections of the bourgeoisie and nobility were interested in the new way of living their faith, which was an important part of their lifestyle. The new teachings were a symbol of the new self-image and social significance that craftsmen, skilled labourers and entrepreneurs in this emerging industry had compared to the old system of feudal lords.

Ferdinand I and his successors were able to successfully push back the Reformation in Tyrol. Although the religious mandates with their numerous prohibitions were one of the reasons for the peasant wars, in the long term and with many coercive measures, the princely strategy bore fruit. Power politics may have been one reason, but in fact the ruling Habsburgs were pious people who, at least to a large extent, favoured Catholicism out of conviction. Ferdinand II described his motives with the words:

"...aus eingebung Gotes und seines Hayligen Geistes Inspiration. Alles zu ehre des aller höchsten aus ainem Rechen inprünstigen zu der heyligen Catholischen Alleinsseligmachenden Religion tragenden eyfer.“

It was primarily priests of the Jesuit order who were to bring apostate parishes and citizens back into the fold of the Catholic Church. They began with reform measures such as better training for the clergy. Concubinage and post haggling were to be abolished. Priests and bishops were to concern themselves less with worldly matters and more with the salvation of their flocks. However, as this measure could not be implemented overnight - capable priests first had to be found and educated - coercive measures were introduced. The possession of Protestant books and pamphlets was punishable by law. The lower the status of the citizen, the more severe the punishment. Nobles, counsellors and key workers were often able to practise their Protestant faith discreetly. Under Ferdinand II, underlings had to confess at Easter. The priest drew up a list with the names of those who fulfilled their duty. Anyone who did not appear in the confessional despite repeated reminders could be expelled from the country.

In the 17th century, Austria used so-called Religious Reformation Commissions in. Did these "Missionare" Protestant-oriented pastors or subjects who possessed forbidden literature were arrested and expelled from the country, and it was not uncommon for their houses to be set on fire along with all their possessions. Protestant civil servants could not practise their profession. They either had to convert or emigrate. Particularly stubborn subjects were publicly chained. Maximilian III had his own Religious agitation The police controlled craftsmen and traders in particular. They had to regularly hand in confession slips to certify their catholicity.

Under Maria Theresia In the 18th century, Tyrolean Protestants were forcibly resettled in remote parts of the Habsburg Empire. However, the resettlements were not only a problem for the citizens concerned. Labour power and the number of subjects were important features of development in modern states. This meant that the problem, which today is known as Braindrain was labelled. Expertise and military power were lost in the name of the Lord.

In 1781, the enlightened Emperor Joseph II issued the Toleranzpatent, das den Bau von protestantischen Kirchen erlaubte, wenn auch an Bedingungen gebunden. So durften diese Bethäuser keine Türme oder sonstigen baulichen Besonderheiten aufweisen. Die Gebäude durften keine straßenseitigen Fenster haben. In Tirol kam es zu Widerständen gegen das Toleranzpatent, man fürchtete um die guten Sitten und wollte fremdartige Religionen, Zwietracht und Unruhen aller Art vermeiden. Konvertierten Untertanen wurden Dinge wie Ehe und ein Begräbnis auf katholischen Friedhöfen verwehrt.

Bis heute gilt Tirol als selbsternanntes „Heiliges Land", whereby holy refers explicitly to the Catholic faith. Protestants were deported from the Zillertal as late as 1837. The descendants of the so-called Zillertaler Inklinantenwho emigrated under pressure from the authorities still live in Germany today. Tolerance gradually found its way into the empire and the provinces, but well into the 20th century, the affiliation between the authorities and the Catholic Church was firmly established in many areas of life, such as school education. When it became known during the constitutional negotiations of 1848 that the free exercise of religion was planned for the entire monarchy, public outrage in Tyrol was enormous. More than 120,000 signatures were collected following media campaigns against this liberalisation of religion. In 1861, Emperor Franz Josef issued the ProtestantenpatentThe Tyrolean government granted the Protestant Church more or less the same rights as the Catholic Church. The Tyrolean population did not allow their perseverance to be undermined by the imperial Protestantenpatent von ihrer Intoleranz abbringen. Das Argument lautete, dass es in Tirol ohnehin keine Andersgläubigen gäbe, es daher auch keiner Toleranz gegenüber Nichtkatholiken bedurfte. Erst 1876 kam es zur Gründung einer evangelischen Pfarrgemeinde in Innsbruck.

Reform and rebellion: Jakob Hutter and Michael Gaismair

The first years of Emperor Ferdinand I's reign (1503 - 1564) as sovereign of Tyrol were characterised by theological and social unrest. Theological and social tensions increased during this crisis-ridden period. Siegmund's lavish court management and Maximilian's wars, including the pledging of a large part of the state's assets to foreign entrepreneurs and financiers, had put Tyrol's financial situation in dire straits. The new law, which had been introduced by Maximilian's administration, stood in contrast to the old customary law. Hunting in the forest and searching for firewood had thus become illegal for the majority of the population. The loss of these Universal rights and the ever-increasing burden of taxes had a negative impact on small farmers, day labourers, farmhands and other labourers. Pofel massive impact. In Tyrol at this time, Jakob Hutter (1500 - 1536) and Michael Gaismair (1490 - 1532) were two men who demanded more social justice, threatened the existing order and paid for it with their lives.

Jakob Hutter was the figurehead of the Anabaptists active in Tyrol, particularly in the Lower Inn Valley and the Puster Valley. The first signs of the Little Ice Age caused an increase in crop failures. Many people saw this as a punishment from God for people's sinful lives. Sects such as the Anabaptists preached the pure doctrine of religion in order to free themselves from this guilt and restore order. The Roman Church and Ferdinand I were particularly displeased by their attitude towards worldly possessions, infant baptism and their open dislike of secular and ecclesiastical authorities. People should freely express their will to join Christianity as adult and responsible citizens and not be baptised as babies.

The Anabaptists posed a threat to public order for the strictly religious Prince Ferdinand, who was loyal to the Pope. A large proportion of the population, groaning under the financial difficulties following Maximilian's expensive reign, welcomed them as scapegoats who brought disaster upon the country with their godless behaviour. Rejecting Catholicism as a guiding social principle in the 16th century would be comparable to denying the existence of the Republic of Austria as a state authority by political extremists. The witch craze passed Innsbruck by, but as early as 1524 three Anabaptists in Innsbruck were tried before the Goldenen Dachl burnt at the stake for heresy. Five years later, following a letter from Ferdinand, thousands of Anabaptists were expelled from the country and emigrated to Moravia, today's Czech Republic, where they were tolerated.

One of them was Hutter. Having grown up in South Tyrol, his apprenticeship and journeyman years as a hatter took him to Prague and Carinthia, where he probably first came into contact with the Anabaptists and their teachings. When the religious community was also expelled from Moravia in 1535, Jakob Hutter returned to Tyrol. He was captured, taken to Innsbruck and imprisoned in the Kräuterturm tortured. As the leader of the heretics for his activities in 1536, he was tried before the Goldenen Dachl burnt at the stake.

The community of Hutterischen Brüder kam nach ihrer endgültigen Vertreibung aus den deutschen Ländern und langen Irrfahrten und Fluchten quer durch Europa im 19. Jahrhundert in Nordamerika an. Noch heute gibt es einige hundert Hutterer Kolonien in Kanada und den USA, die noch immer nach dem Gebot der Jerusalemer Gütergemeinschaft in einer Art kommunistischem Urchristentum leben. Wie die Mennoniten und die Amisch leben die Hutterer meist isoliert von der Außenwelt und haben sich eine eigene Form der an das Deutsche angelehnten Sprache erhalten. In Innsbruck erinnern eine kleine Tafel am Goldenen Dachl sowie eine Straße im Westen der Stadt an Jakob Hutter. 2008 hatten die Bischöfe von Brixen und Innsbruck gemeinsam mit den Landeshauptleuten Nord- und Südtirols in einem Brief an den Ältestenrat der Hutterischen Brüder das knapp 500 Jahre vergangene Unrecht an der Täufergemeinschaft eingestanden. 2015 wurde im Saggen eein paar Schritte südwestlich des Panoramagebäudes der Huttererpark eröffnet, in dem das Denkmal „Übrige Brocken“ an das Schicksal und Leid der Verfolgten erinnert.

Der größte Aufruhr im Zuge der Reformation in Tirol war der Bauernaufstand ab 1525, der eng mit dem Namen Michael Gaismairs verbunden ist. Anders als Hutter, der vor allem eine spirituelle Erneuerung forderte, wollte Gaismair auch soziale Veränderungen vorantreiben. Der Tiroler Aufstand war ein Teil dessen, was als Deutscher Bauernkrieg große Teile des Heiligen Römischen Reiches was shaken. It was partly reformist, theological fervour, partly dissatisfaction with the social situation and distribution of goods that drove the rebels. Gaismair was not a theologian. He was the son of a mining entrepreneur, one could say educated middle class. He probably studied law at an Italian university before becoming a mine clerk at the Schwaz mine. In 1518 he entered the service of the Tyrolean governor Leonhard von Völs, where he gained military and administrative experience. In 1524, presumably after some kind of corruption scandal, he moved into the service of the Bishop of Brixen. The bishop was both the ecclesiastical and secular prince of his diocese. He was very unpopular with his subjects, as he was considered a strict ruler and demanded more robbery and indentured labour than the Tyrolean ruler. Here, Gaismair saw first-hand how the clergy's sovereign administration and strict jurisdiction enslaved the subjects.

In May 1525, he took part in one of the uprisings, which were also fuelled by news of the peasant uprisings in southern Germany. Many of the Tyrolean subjects had served as soldiers in Maximilian's Italian wars and had military experience. Although they had no cavalry at their disposal and lacked strategic leadership, some of the groups were organised in a military sense. They were joined by discontented townspeople, handers and other Pofel. One of these bands of peasants invaded the Neustift monastery. Not only were the bishop's property and wine stocks plundered, but the Urbare, the records relating to jurisdiction, property, debts and obligations of the peasants to the lord of the manor, were also destroyed. The day after the monastery was taken, the rebels elected Gaismair as their captain. It was probably his military experience, his education and his knowledge of the military strengths and weaknesses of both the governor of Tyrol and the bishops of Brixen and Trento that earned him their trust.

Over the next few days, the uprising gained momentum in an uncoordinated manner and spread across large parts of Tyrol. There were attacks on church institutions and hated foreign trading organisations such as the Fuggers. While some of the detachments and groups made serious demands and posed a real threat to the authorities, others were out for the fun of rebellion and looting. In Innsbruck, Wilten Abbey was besieged as a manorial seat, but the peasants quickly abandoned their plan after receiving wine and meat from the abbot's storehouses.

In order to gain time and gather together, the government under Ferdinand convened a provincial parliament in Innsbruck. The concerns of the subjects were set out in a catalogue of complaints, the 62 Merano articles collected later on 96 Innsbruck articles were extended. During the negotiations between the sovereigns, nobility, clergy, burghers and peasants, Gaismair continued to reside in Brixen and tried to establish his regiment in the area along the Eisack.

It was only during the summer that he travelled to Innsbruck to negotiate with Ferdinand. Although he was promised free passage, the man who represented the greatest danger in the eyes of the authorities was imprisoned. After his rather unspectacular escape in October 1525, it seems unlikely that he was actually imprisoned in the Kräuterturm. After some time in his home town of Sterzing, the prince's troops seem to have been unable to gain access to the Most Wanted having had a chance, he travelled to the Swiss West. In Zurich, he met Huldyrich Zwingli. Probably inspired by him, Gaismair wrote a draft for a Tyrolean constitution. The clergy were to concern themselves with the salvation of their subjects rather than politics. Land and goods such as mining yields were to be distributed in a socially just manner and interest was to be abolished. The restrictions on hunting and fishing imposed on the Tyroleans by Ferdinand's predecessor Maximilian I were to be lifted. One of the articles read:

„As far as the tithe is concerned, everyone should give it according to the commandment of God, and it should be used as follows: Let every parish have a priest according to the teaching of the Apostle Paul, whom the word of God proclaims to the people... what is left over is to be given to the poor."