The Wallschen and the Fatti di Innsbruck

The Wallschen and the Fatti di Innsbruck

Prejudice and racism towards immigrants were and are common in Innsbruck, as in all societies. Whether Syrian refugees since 2015 or Turkish guest workers in the 1970s and 80s, the foreign usually generates little well-disposed animosity in the average Tyrolean. Today, Italy may be Innsbruck's favourite travel destination and pizzerias part of everyday gastronomic life, but for a long time our southern neighbours were the most suspiciously eyed population group. What the Viennese Jew and Brick Bohemia were the Tyrolean's Wall's.

The aversion to Italians in Innsbruck can look back on a long tradition. Although Italy did not exist as an independent state, the political landscape was characterised by many small counties, city states and principalities between Lake Garda and Sicily. The individual regions also differed in terms of language and culture. Nevertheless, over time people began to see themselves as Italians. During the Middle Ages and the early modern period, they were mainly resident in Innsbruck as members of the civil service, courtiers, bankers or even wives of various sovereigns. The antipathy between Italians und Germans was mutual. Some were regarded as dishonourable, unreliable, snobbish, vain, morally corrupt and lazy, others as uncivilised, barbaric, uneducated and pigs.

With the wars between 1848 and 1866, hatred of all things Italian reached a new high in the Holy Land Tyrolalthough many Wallsche served in the k.u.k. army and most of the rural population among the Italian-speaking Tyroleans were loyal to the monarchy. The Italians under Garibaldi were regarded as godless rebels and republicans and were castigated from the church pulpits between Kufstein and Riva del Garda in both Italian and German.

The Tyrolean press landscape, which experienced an upswing after liberalisation in 1867, played a major role in the conflict. What today Social Media The newspapers of the time took over the role of the press, which contributed to social division. Conservatives, Catholics, Greater Germans, liberals and socialists each had their own press organs. Loyal readers of these hardly neutral papers lived in their opinion bubble. On the Italian side, the socialist Cesare Battisti (1875 - 1916), who was executed by the Austrian military during the war for high treason on the gallows, stood out. The journalist and politician, who had studied in Vienna and was therefore considered by many to be not just an enemy but a traitor, fuelled the conflict in the newspapers Il Popolo und L'Avvenire repeatedly fired with a sharp pen.

Associations also played a key role in the hardening of the fronts. Not only had the press law been reformed in 1867, but it was now also easier to found associations. This triggered a veritable boom. Sports clubs, gymnastics clubs, theatre groups, shooting clubs and the Innsbrucker Liedertafel often served as a kind of preliminary organisation that took a political stance and also agitated. The club members met in their own pubs and organised regular club evenings, often in public. The student fraternities were particularly politically active and extremist in their opinions. The young men came from the upper middle classes or the aristocracy and were used to buying and carrying weapons. A third of the students in Innsbruck belonged to a fraternity, of which just under half were of German nationalist orientation. Unlike today, it was not uncommon for them to appear in public in their full dress uniform, complete with sabre, beret and ribbon, often armed with a cane and revolver.

It is therefore not surprising that their habitat was a particular flashpoint. One of the biggest political points of contention in the autonomy debate and the desire to join the Kingdom of Italy was a separate Italian university. The loss of Padua meant that Tyroleans of Italian descent no longer had the opportunity to study in their native language at home. Although attending the university was actually only a matter for a small elite, irredentist, anti-Austrian Tyrolean members of parliament from Trentino were able to emotionally charge the issue again and again as a symbol of the desired autonomy and fuelled hatred of Habsburg. The debate as to whether a university in Trieste, the favoured location of the Italian-speaking representatives, Innsbruck, Trento or Rovereto should be targeted, went on for years. Wilhelm Greil was admonished for his incorrect behaviour towards the Italian population by the Imperial-Royal Governor. All language groups within the monarchy were to be treated equally by law from 1867 onwards.

A look at the statistics shows just how great the fears of German nationalists that Italian students would overrun the country were. Even then, facts were often replaced in the discourse by gut feelings and racially motivated populism. After the incorporation of Pradl and Wilten in 1904, Innsbruck had just over 50,000 inhabitants. The proportion of students was just over 1000 and less than 2%. Of the approximately 3000 people of Italian descent, most of them Welschtiroler from Trentino, only just over 100 were enrolled at the university. The majority of the Wallschen made up labourers, innkeepers, traders and soldiers. Many had been living in and around Innsbruck for a long time. Many settled in Wilten in particular. Soon a small diaspora came together in the somewhat more favourable workers' village on the lower town square. Anton Gutmann sold Italian wines in his winery cooperative Riva in Leopoldstraße 30, and across the street you could eat well and cheaply at the Gasthaus Steneck specialities south of the Brenner. The majority were part of a different everyday culture, but as subjects of the monarchy they spoke excellent German; only a small proportion came from Dalmatia or Trieste and were actually foreign speakers. In keeping with the spirit of the times, they also founded sports clubs such as the Club Ciclistico oder die Unione Ginnasticasocialist-oriented workers' and consumer organisations, music clubs and student fraternities.

Although the students only made up a small proportion of them, they and the demand for an institute with Italian as the language of examination and teaching received above-average attention. Conservative and German nationalist politicians, students and the media saw an Italian university as a threat to Tyrolean Germanness. In addition to the ethnic and racist resentment towards the southern neighbours, Catholics in particular were also afraid of characters such as Cesare Battisti, who, as a socialist, embodied evil incarnate. Mayor Wilhelm Greil capitalised on the general hostility towards Italian-speaking residents and students in a similar populist manner as his Viennese counterpart Karl Lueger did in Vienna with his anti-Semitic propaganda.

After some back and forth, it was decided in September 1904 to establish a provisional law faculty in Innsbruck. This was intended to separate the students without marginalising one of the groups. From the outset, however, the project was not under a favourable star. Nobody wanted to rent the necessary premises to the university. Finally, the enterprising master builder Anton Fritz made a flat available in one of his tenement houses at Liebeneggstraße 8. At the inaugural lecture and the festive evening event in the White Cross Inn On 3 November, celebrities such as Battisti and the future Italian Prime Minister Alcide de Gasperi were in attendance. The later the evening, the more exuberant the atmosphere. When shouts of invective such as "Porchi tedeschi“ and „Abbasso Austria" (Note: German pigs and down with Austria), the situation escalated. A mob of German-speaking students armed with sticks, knives and revolvers laid siege to the White cross, in which the Italians, who were also largely armed, entrenched themselves. A troop of Kaiserjäger successfully broke up the first riot. In the process, the painter August Pezzey (1875 - 1904) was accidentally fatally wounded by an overly nervous soldier with a bayonet thrust.

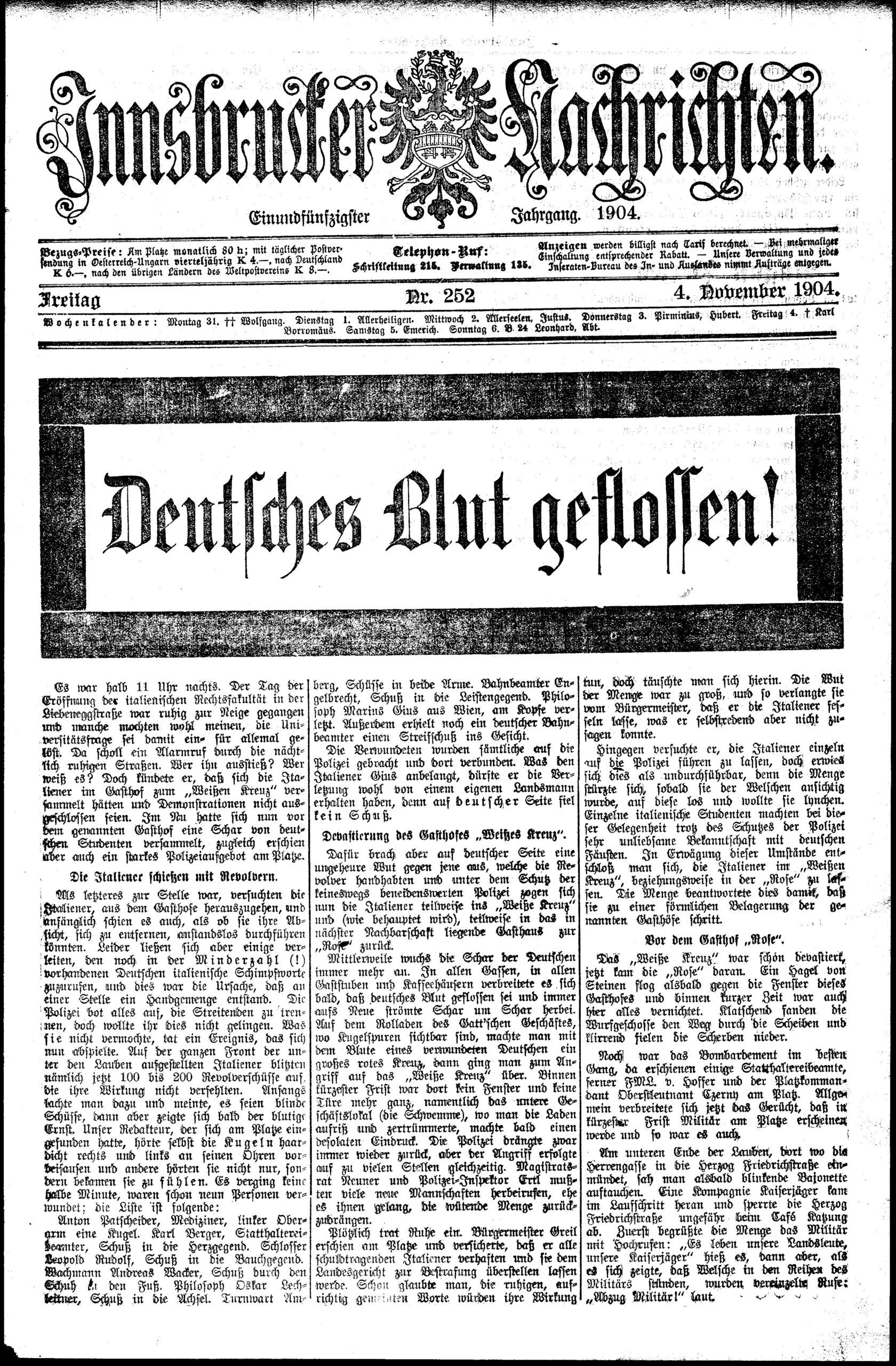

The Innsbrucker Nachrichten appeared after the night-time activities on 4 November under the headline: "German blood has flowed!". The editor present reported 100 to 200 revolver shots fired by the Italians at the "Crowd of German students" who had gathered in front of the White Cross Inn. The nine wounded were listed by name, followed by an astonishingly detailed account of what had happened, including Pezzey's wound. The news of the young man's death unleashed a storm of acts of revenge and violence. As with every riot, the convinced German nationalists were joined by onlookers and rioters who enjoyed going overboard in the anonymity of the crowd without any great political conviction. While the detained Italians in the completely overcrowded prison sang the martial anthem Inno di Garibaldi the city saw serious riots against Italian restaurants and businesses. The premises of the White Cross Inn were completely vandalised except for a portrait of Emperor Franz Josef. Rioters threw stones at the residence of the governor, Palais Trapp, as his wife had Italian roots. The building in Liebeneggstraße, which Anton Fritz had made available to the university, was destroyed, as was the architect's private residence.

August Pezzey, who died in the turmoil and came from a Ladin family, was declared a "German hero" in a national frenzy by politicians and the press. He was given a grave of honour at Innsbruck's West Cemetery. At his funeral, attended by thousands of mourners, Mayor Greil read out a pathetic speech:

"...A gloriously beautiful death was granted to you on the field of honour for the German people... In the fight against impudent acts of violence you breathed your last as a martyr for the German cause..."

Reports from the Fatti di Innsbruck made it into the international press and played a decisive role in the resignation of Austrian Prime Minister Ernest von Koerber. Depending on the medium, the Italians were portrayed as dishonourable bandits or courageous national heroes, the Austrians as pan-Germanist barbarians or bulwarks against the Wallsche seen. On 17 November, just two weeks after the ceremonial opening, the Italian faculty in Innsbruck was dissolved again. The language group was denied its own university within Austria-Hungary until the end of the monarchy in 1918. The long tradition of viewing Italians as dishonourable and lazy was further fuelled by Italy's entry into the war on the side of the Entente. To this day, many Tyroleans keep the negative prejudices against their southern neighbours alive.

German blood flowed

Published: Innsbrucker Nachrichten / 4 November 1904

It was half past ten at night. The day of the opening of the Italian law school in Siebenengasse had ended quietly, and some might have thought that the unrest had been settled once and for all. Then a warning cry rang out through the quiet night-time streets. Who was shouting it? Who knows? But it soon turned out that the Italians had gathered at the "White Cross" inn and that demonstrations were not over. And soon a crowd of German students had gathered in front of the inn, but at the same time a large contingent of police appeared on the scene.

The Italians shoot with revolvers.

When representatives of the local force had come to the scene, disarming them in vain, it seemed at first as if the Italians would have to leave without objection. But it soon came to light that the Italians gathered in the "Weißes Kreuz" inn suddenly fired a volley of insults, which was soon followed by an immediate scuffle. The police did all they could to separate the quarrelling parties, but force had to be used, and an event developed that ended in bloodshed. A bloody catastrophe occurred in the open alley. Italians shot wildly and one of the German students was left bleeding on the ground. Two bullets hit him in the arm, one in the neck. Blood flowed. Shots rang out. More Germans were seriously injured, shot in both arms. Railway official Gruber injured, shot in the lower region. Physicist, German student from Vienna, injured in the head. A German railway official also suffered a graze shot to the face.

The revolt could only be suppressed by force by the police. Soon 300 Italians had gathered, and the wounded formed their own medical detachment, as a seriously wounded man fell on the German side.

Declaration of the "Weißes Kreuz" inn.

On the German side, a tremendous rage erupted against those who committed the acts of violence and, under the protection of the Italian demonstrators, the police against their brothers, covering the Italians with weapons. And this slogan, which fortunately prevailed during the last night of terror, led to the terrible catastrophe.

Immediately the German gunfire increased. In every corner, in every alley, the most terrible threats. Italians and German students were clashing weapons. What a terrible night! A sea of blood, of revolver shots through the streets, and the terrible experience of several German students falling to the ground in the street, covered in blood. One was grazed in the face, another shot in the chest, a third shot in the arm.

Finally, the police intervened. The Italians were forced back into the alleyways at point-blank bayonets. With terrible noise, wild shouting, insults and threats on their lips. Shots rang out once more and an Italian fell, badly hit. Finally the crowd dispersed.

Still on Friday morning.

On Friday morning the streets were still full of pools of blood, the blood of the wounded was still pouring out of the pavement joints and could not be stopped.

It became more and more obvious that the Italians, mindful of the police, were shooting at them and thus taking all the blame. It is indisputable that the crowd only had to defend itself, and that such a terrible event arose from the behaviour of the Italian students.

The opportunity was taken to close the "White Cross" because of its German blood and undeniable illegality. On Friday, remodelling work again. Soon the building was in flames. It was a new "liberation attempt".

The crowd demanded this so that the name "White Cross" would disappear from the city forever.

Sights to see...

Leopoldstraße & Wiltener Platzl

Leopoldstrasse

Fraternity House Austria

Josef-Hirn-Straße

University of Innsbruck

Innrain 52