Wilten & Sieglanger

Things to know about Wilten

Judging by archaeological finds, Wilten could be described as Innsbruck's nucleus. A large number of graves, wall remains, coins, pottery and water channels were unearthed during excavations between Mount Isel and the Olympic Bridge. After the Roman colonisation of the Inn Valley around the turn of the century, a military base was established. This Castell Veldidena developed into the first recorded settlement in 806. Locus Wiltina. After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD, Tyrol slowly and insidiously came under the control of the Duchy of Bavaria. By 1180, when the Counts of Andechs began to establish the market on the southern bank of the Inn, from which Innsbruck was to emerge, Wilten had already been around for a thousand years.

The seamless transition from the Romans to the Bavarians without any loss of importance was due to the clerical structures. Christianity and Wilten Abbey were established institutions. The new rulers were only too happy to take over this local ecclesiastical and political administrative centre. In order to expand their new settlement at the Inn bridge, the Andechs had to wrest the land from the monastery. Not only in 1180, but also in 1339 and 1453, the expansion of Innsbruck could only take place after the land had been acquired from the Wilteners. With great foresight, Wilten Abbey had special rights contractually enshrined in return. As a result, the city was dependent on the community south of the city in many respects. The Small SillThe canal, which was built in the High Middle Ages, supplied the town with water, which was essential for the town's trades. As the canal flowed through the lands of Wilten Abbey, the abbot had the power of disposal over the right of use until the 16th century, as he did over so many other things. The abbey also owned the important milling rights. In the Middle Ages, farmers from Amras, Pradl and Innsbruck had to make a pilgrimage to the Wilten mills on the Sill to grind their grain. If medieval towns ran out of bread, there was a risk of unrest and riots, as grain was the main ingredient in the daily diet.

Throughout the centuries, Wilten was primarily important as an ecclesiastical authority. The relationship between the ecclesiastical power in Wilten in the person of the abbot and the secular power in Innsbruck in the person of the sovereign, supported by the Jesuits from the 16th century onwards, was similar to the ongoing dispute between the Pope and the Emperor in the Middle Ages. The town was dependent on the abbot in matters of pastoral care and the mass service. The parish church of St Jakob was merely a branch of Wilten Abbey. Until 1560, Wilten Abbey successfully prevented further monastery settlements in Innsbruck in order to maintain its sphere of influence in the city. It was only during the Reformation that Ferdinand I, a prince from Spain who disregarded many local customs and later Emperor, managed to establish a monastery in the city. At his insistence, the Jesuits came to the court in 1561, followed shortly afterwards by the Franciscans. Masses on high holidays such as Christmas, Easter and baptisms were still celebrated in Wilten.

Wilten, separated by a customs border, moved in step with Innsbruck for a long time. Although the settlement did not have a town charter, walls or a town tower, the village grew rapidly northwards from the monastery. Farmers and craftsmen settled between the Triumphal Gate and the basilica. The abbot not only raised the Zehenten but also supervised the legal and economic agendas of his flock. From the 17th century onwards, some of the farmhouses in the upper village behind the basilica and in the lower village on today's Wiltener Platzl were converted into aristocratic residences. In the second half of the 19th century, the bourgeoisie took over. This development can be traced in the buildings in Haymongasse and Rote Gasse behind Wilten Basilica. Magnificent houses still stand here today, such as the Haymon Giant Inn with a Gothic centre.

With the developments of the second half of the 19th century, Wilten and Innsbruck grew together economically and socially. The Brenner railway in 1867 and the Arlbergban in 1884 changed the district considerably. From the 1860s onwards, the area between Innrain and Südring, along the old country lanes of the agricultural area to the south and west of the city, saw the construction of residential buildings and apartment blocks, many of which are still worth seeing today, in which employees and workers lived. Innsbruck residents had businesses in Wilten and vice versa. The customs border at the Triumphpforte became more and more of an absurdity. Foodstuffs such as beer, wine, meat and grain traded between Innsbruck and Wilten had to be cleared through customs. The internal customs duty on basic foodstuffs was perceived as harassment. The so-called Akzise was hated by citizens on both sides, as it made daily life unnecessarily expensive. The building, which is clearly recognisable in archive photos Accis-Häuschen after unification and the discontinuation of the Viennese Bazaar a kind of early shopping centre.

In 1904, Wilten officially became a district of Innsbruck. The last head of the municipality Fritz Heigl (1856 - 1923) and building planner Rudolf Tschamler negotiated the points of the agreement to unite Innsbruck and Wilten with a committee led by Wilhelm Greil from Innsbruck. The population had tripled within a few decades. The expensive infrastructure could not be developed by the municipality. Water and electricity changed people's everyday lives and standard of living, but first had to be financed. Around 1900, Wilten only had one school for over 10,000 inhabitants, while Innsbruck had six for 25,000. Carrying out the modernisation in Wilten and Innsbruck together was sensible both organisationally and financially, which did not mean that old-established Wilten residents did not still bemoan the lost village character decades later, even if at least the Wilten music band and the Wilten marksmen continued to be financed by Innsbruck as part of the agreement. With the first tram from Berg Isel through Wilten to the main railway station in 1905, the marriage went from being a legal contract to an actual act.

Much bears witness to this growth and the incorporation of the town at the turn of the century, which was largely driven by Greater German Liberal politicians. In Wilten, the "Helden“ of the Tyrolean uprising of 1809 is immortalised in street names such as Andreas-Hofer-Straße, Speckbacherstraße or Haspingerstraße. The town also grew westwards along Anichstraße to the clinic and the Westfriedhof cemetery during this period. A short walk from Anichstraße through Kaiser-Josef-Straße, Speckbacherstraße, Stafflerstraße to Sonnenburgstraße gives a good impression of urban development between 1880 and 1945. The Wilhelminian style houses are just as worth seeing as the Südtirolersiedlung. In the post-war period, after an initial planning phase at the turn of the century, the parish of the Holy Family was built next to the Westfriedhof cemetery 50 years late in order to accommodate the city's growth in terms of pastoral care. For decades, the people of Wilten who did not belong to the parish of the Sacred Heart in Maximilianstraße or the basilica had to celebrate services in various makeshift churches. In 1957, Bishop Paulus Rusch was able to consecrate the first church with truly modern architecture.

Apart from folklore, there is hardly anything left to remind us of the separation between Wilten and Innsbruck. To celebrate the unification of Wilten and Innsbruck, Johann von Sieberer had the Unification fountain at the railway station, which was removed under the National Socialists to make more room for traffic. Two boundary stones with the coats of arms of Innsbruck and Wilten were also walled into the bay window on the ground floor on the outer wall of the Hotel Goldene Krone Today, Wilten is a diverse and lively neighbourhood. Between the Upper village Around Gasthaus Haymon, Wilten West near the cemetery and the Triumphpforte, you will find traditional and new city life in close proximity. Functional housing from the 1960s and 1970s meets baroque town houses. The proximity to the university and hospital in combination with the spacious flats in old buildings make Wilten attractive for students. In quaint pubs such as the Jolly treffen alteingesessene Wiltener auf junges Publikum.

Interesting facts about the Sieglanger

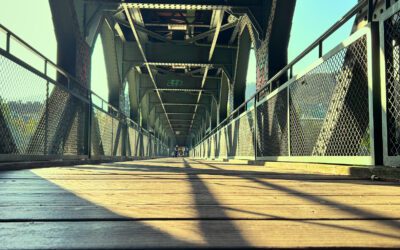

The Sieglanger in the west of the city was a fief of Wilten Abbey, on which a manor house was built in the 15th century, today's Mentlberg Castle. Historical maps show the differences between the undeveloped state in 1930 in various stages up to the densified settlement from 1980 onwards. In the 19th century, the area on which the still popularly known Zieglstadl a brickworks stands on the site of the prison. Today's Sieglanger am Inn was a Lower Figge known and undeveloped. After the Second World War, Sieglanger became more densely populated. Sieglanger's heyday came during the period of the economic miracle after the Second World War. In 1962, the church was Maria on the shore opened. The church with its striking tower, visible from afar, and the concrete and glass wall with its colourful windows, designed by Max Weiler, is a monument to Tyrol's new beginnings. Two years later, the motorway was built, a less picturesque boundary to the district. Since 1977, the impressive Sieglangersteg bridge with a span of 147 metres over the motorway and the River Inn has connected Sieglanger for cyclists and pedestrians with two other settlements, the former Neustädter Stürmer settlement on the Lohbach and the Höttinger Au.

Western cemetery

Fritz-Pregl-Straße

Tram line 6

Stops: Mühlau - Igls

Adambräu & Ansitz Windegg

Adamgasse 23

Sill Gorge

Wilten

Haymon Giant Inn

Haymongasse 4

Tyrolean Glass Painting and Mosaic Institute

Müllerstrasse 10

Sonnenburgplatz

Sonnenburgstraße

Leopoldstraße & Wiltener Platzl

Leopoldstrasse

Mentlberg Castle & Pilgrimage Church

Mentlberg 23

Karwendel bridge

Karwendel arches

Provincial vocational school

Mandelsbergerstrasse 16

Fraternity House Austria

Josef-Hirn-Straße

South Tyrolean settlement Wilten West

Speckbacherstrasse

Johanneskirche

Bischof-Reinhold-Stecher-Platz

Dollfußsiedlung & Fischersiedlung

Weingartnerstrasse

Mountain Isel

Mountain Isel 1

Winklerhaus

Leopoldstraße/Maximilianstraße

University of Innsbruck

Innrain 52

Wilten Abbey & Basilica

Klostergasse 7 / Pastorgasse 2