A First Republic emerges

A republic is born

Few eras are more difficult to grasp than the interwar period. The Roaring TwentiesJazz and automobiles come to mind, as do inflation and the economic crisis. In big cities like Berlin, young ladies behaved as Flappers mit Bubikopf, Zigarette und kurzen Röcken zu den neuen Klängen lasziv, Innsbrucks Bevölkerung gehörte als Teil der jungen Republik Österreich zum größten Teil zur Fraktion Armut, Wirtschaftskrise und politischer Polarisierung. Schon die Ausrufung der Republik am Parlament in Wien vor über 100.000 mehr oder minder begeisterten, vor allem aber verunsicherten Menschen verlief mit Tumulten, Schießereien, zwei Toten und 40 Verletzten alles andere als reibungsfrei. Wie es nach dem Ende der Monarchie und dem Wegfall eines großen Teils des Staatsterritoriums weitergehen sollte, wusste niemand. Das neue Österreich erschien zu klein und nicht lebensfähig. Der Beamtenstaat des k.u.k. Reiches setzte sich nahtlos unter neuer Fahne und Namen durch. Die Bundesländer als Nachfolger der alten Kronländer erhielten in der Verfassung im Rahmen des Föderalismus viel Spielraum in Gesetzgebung und Verwaltung. Die Begeisterung für den neuen Staat hielt sich aber in der Bevölkerung in Grenzen. Nicht nur, dass die Versorgungslage nach dem Wegfall des allergrößten Teils des ehemaligen Riesenreiches der Habsburger miserabel war, die Menschen misstrauten dem Grundgedanken der Republik. Die Monarchie war nicht perfekt gewesen, mit dem Gedanken von Demokratie konnten aber nur die allerwenigsten etwas anfangen. Anstatt Untertan des Kaisers war man nun zwar Bürger, allerdings nur Bürger eines Zwergstaates mit überdimensionierter und in den Bundesländern wenig geliebter Hauptstadt anstatt eines großen Reiches. In den ehemaligen Kronländern, die zum großen Teil christlich-sozial regiert wurden, sprach man gerne vom Viennese water headwho was fed by the yields of the industrious rural population.

Other federal states also toyed with the idea of seceding from the Republic after the plan to join Germany, which was supported by all parties, was prohibited by the victorious powers of the First World War. The Tyrolean plans, however, were particularly spectacular. From a neutral Alpine state with other federal states, a free state consisting of Tyrol and Bavaria or from Kufstein to Salurn, an annexation to Switzerland and even a Catholic church state under papal leadership, there were many ideas. The most obvious solution was particularly popular. In Tyrol, feeling German was nothing new. So why not align oneself politically with the big brother in the north? This desire was particularly pronounced among urban elites and students. The annexation to Germany was approved by 98% in a vote in Tyrol, but never materialised.

Instead of becoming part of Germany, they were subject to the unloved Wallschen. Italian troops occupied Innsbruck for almost two years after the end of the war. At the peace negotiations in Paris, the Brenner Pass was declared the new border. The historic Tyrol was divided in two. The military was stationed at the Brenner Pass to secure a border that had never existed before and was perceived as unnatural and unjust. In 1924, the Innsbruck municipal council decided to name squares and streets around the main railway station after South Tyrolean towns. Bozner Platz, Brixnerstrasse and Salurnerstrasse still bear their names today. Many people on both sides of the Brenner felt betrayed. Although the war was far from won, they did not see themselves as losers to Italy. Hatred of Italians reached its peak in the interwar period, even if the occupying troops were emphatically lenient. A passage from the short story collection "The front above the peaks" by the National Socialist author Karl Springenschmid from the 1930s reflects the general mood:

"The young girl says, 'Becoming Italian would be the worst thing.

Old Tappeiner just nods and grumbles: "I know it myself and we all know it: becoming a whale would be the worst thing."

Trouble also loomed in domestic politics. The revolution in Russia and the ensuing civil war with millions of deaths, expropriation and a complete reversal of the system cast its long shadow all the way to Austria. The prospect of Soviet conditions machte den Menschen Angst. Österreich war tief gespalten. Hauptstadt und Bundesländer, Stadt und Land, Bürger, Arbeiter und Bauern – im Vakuum der ersten Nachkriegsjahre wollte jede Gruppe die Zukunft nach ihren Vorstellungen gestalten. Die Kulturkämpfe der späten Monarchie zwischen Konservativen, Liberalen und Sozialisten setzte sich nahtlos fort. Die Kluft bestand nicht nur auf politischer Ebene. Moral, Familie, Freizeitgestaltung, Erziehung, Glaube, Rechtsverständnis – jeder Lebensbereich war betroffen. Wer sollte regieren? Wie sollten Vermögen, Rechte und Pflichten verteilt werden. Ein kommunistischer Umsturz war besonders in Tirol keine reale Gefahr, ließ sich aber medial gut als Bedrohung instrumentalisieren, um die Sozialdemokratie in Verruf zu bringen. 1919 hatte sich in Innsbruck zwar ein Workers', farmers' and soldiers' council nach sowjetischem Vorbild ausgerufen, sein Einfluss blieb aber gering und wurde von keiner Partei unterstützt. Ab 1920 bildeten sich offiziell sogenannten Soldatenräte, die aber christlich-sozial dominiert waren. Das bäuerliche und bürgerliche Lager rechts der Mitte militarisierte sich mit der Tiroler Heimatwehr professioneller und konnte sich über stärkeren Zulauf freuen als linke Gruppen, auch dank kirchlicher Unterstützung. Die Sozialdemokratie wurde von den Kirchkanzeln herab und in konservativen Medien als Jewish Party and homeless traitors to their country. They were all too readily blamed for the lost war and its consequences. The Tiroler Anzeiger summarised the people's fears in a nutshell: "Woe to the Christian people if the Jews=Socialists win the elections!".

With the new municipal council regulations of 1919, which provided for universal suffrage for all adults, the Innsbruck municipal council comprised 40 members. Of the 24,644 citizens called to the ballot box, an incredible 24,060 exercised their right to vote. Three women were already represented in the first municipal council with free elections. While in the rural districts the Tyrolean People's Party as a merger of Farmers' Union, People's Association und Catholic Labour Despite the strong headwinds in Innsbruck, the Social Democrats under the leadership of Martin Rapoldi were always able to win between 30 and 50% of the vote in the first elections in 1919. The fact that the Social Democrats did not succeed in winning the mayor's seat was due to the majorities in the municipal council formed by alliances with other parties. Liberals and Tyrolean People's Party was at least as hostile to social democracy as he was to the federal capital Vienna and the Italian occupiers.

But high politics was only the framework of the actual misery. The as Spanish flu This epidemic, which has gone down in history, also took its toll in Innsbruck in the years following the war. Exact figures were not recorded, but the number of deaths worldwide is estimated at 27 - 50 million. In Innsbruck, at the height of the Spanish flu epidemic, it is estimated that around 100 people fell victim to the disease every day. Many Innsbruck residents had not returned home from the battlefields and were missing as fathers, husbands and labourers. Many of those who had made it back were wounded and scarred by the horrors of war. As late as February 1920, the „Tyrolean Committee of the Siberians" im Gasthof Breinößl "...in favour of the fund for the repatriation of our prisoners of war..." organised a charity evening. Long after the war, the province of Tyrol still needed help from abroad to feed the population. Under the heading "Significant expansion of the American children's aid programme in Tyrol" was published on 9 April 1921 in the Innsbrucker Nachrichten to read: "Taking into account the needs of the province of Tyrol, the American representatives for Austria have most generously increased the daily number of meals to 18,000 portions.“

Then there was unemployment. Civil servants and public sector employees in particular lost their jobs after the League of Nations linked its loan to severe austerity measures. Salaries in the public sector were cut. There were repeated strikes. Tourism as an economic factor was non-existent due to the problems in the neighbouring countries, which were also shaken by the war. The construction industry, which had been booming before the war, collapsed completely. Innsbruck's largest company Huter & Söhne hatte 1913 über 700 Mitarbeiter, am Höhepunkt der Wirtschaftskrise 1933 waren es nur noch 18. Der Mittelstand brach zu einem guten Teil zusammen. Der durchschnittliche Innsbrucker war mittellos und mangelernährt. Oft konnten nicht mehr als 800 Kalorien pro Tag zusammengekratzt werden. Die Kriminalitätsrate war in diesem Klima der Armut höher als je zuvor. Viele Menschen verloren ihre Bleibe. 1922 waren in Innsbruck 3000 Familien auf Wohnungssuche trotz eines städtischen Notwohnungsprogrammes, das bereits mehrere Jahre in Kraft war. In alle verfügbaren Objekte wurden Wohnungen gebaut. Am 11. Februar 1921 fand sich in einer langen Liste in den Innsbrucker Nachrichten on the individual projects that were run, including this item:

„The municipal hospital abandoned the epidemic barracks in Pradl and made them available to the municipality for the construction of emergency flats. The necessary loan of 295 K (note: crowns) was approved for the construction of 7 emergency flats.“

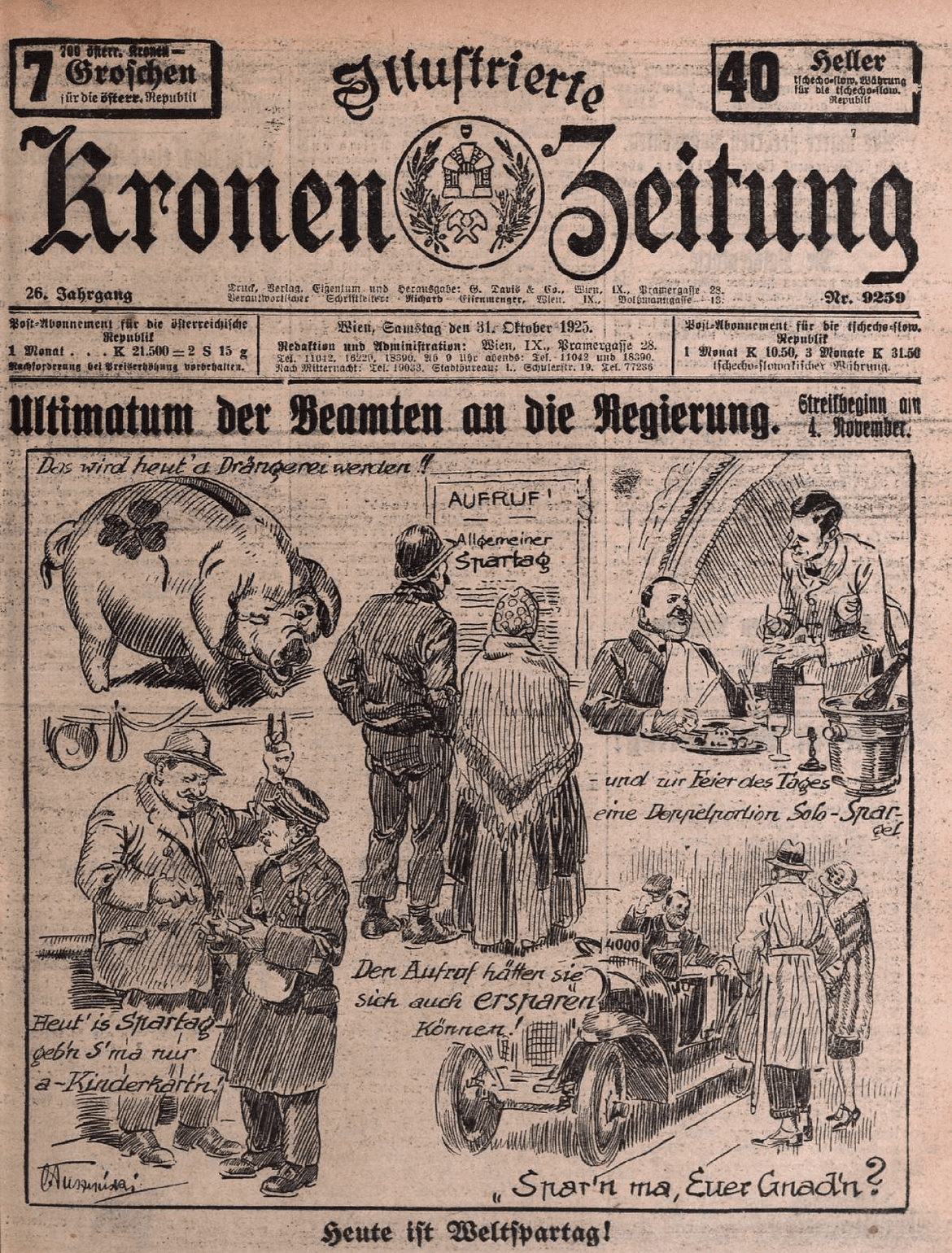

Very little happened in the first few years. Then politics awoke from its lethargy. The crown, a relic from the monarchy, was replaced by the schilling as Austria's official currency on 1 January 1925. The old currency had lost more than 95% of its value against the dollar between 1918 and 1922, or the pre-war exchange rate. Innsbruck, like many other Austrian municipalities, began to print its own money. The amount of money in circulation rose from 12 billion crowns to over 3 trillion crowns between 1920 and 1922. The result was an epochal inflation.

With the currency reorganisation following the League of Nations loan under Chancellor Ignaz Seipel, not only banks and citizens picked themselves up, but public building contracts also increased again. Innsbruck modernised itself. There was what economists call a false boom. This short-lived economic recovery was a Bubble, However, the city of Innsbruck was awarded major projects such as the Tivoli, the municipal indoor swimming pool, the high road to the Hungerburg, the mountain railways to the Isel and the Nordkette, new schools and apartment blocks. The town bought Lake Achensee and, as the main shareholder of TIWAG, built the power station in Jenbach. The first airport was built in Reichenau in 1925, which also involved Innsbruck in air traffic 65 years after the opening of the railway line. In 1930, the university bridge connected the hospital in Wilten and the Höttinger Au. The Pembaur Bridge and the Prince Eugene Bridge were built on the River Sill. The signature of the new, large mass parties in the design of these projects cannot be overlooked.

The first republic was a difficult birth from the remnants of the former monarchy and it was not to last long. Despite the post-war problems, however, a lot of positive things also happened in the First Republic. Subjects became citizens. What began in the time of Maria Theresa was now continued under new auspices. The change from subject to citizen was characterised not only by a new right to vote, but above all by the increased care of the state. State regulations, schools, kindergartens, labour offices, hospitals and municipal housing estates replaced the benevolence of the landlord, sovereigns, wealthy citizens, the monarchy and the church.

To this day, much of the Austrian state and Innsbruck's cityscape and infrastructure are based on what emerged after the collapse of the monarchy. In Innsbruck, there are no conscious memorials to the emergence of the First Republic in Austria. The listed residential complexes such as the Slaughterhouse blockthe Pembaurblock or the Mandelsbergerblock oder die Pembaur School are contemporary witnesses turned to stone. Every year since 1925, World Savings Day has commemorated the introduction of the schilling. Children and adults should be educated to handle money responsibly.

Sights to see...

Western cemetery

Fritz-Pregl-Straße

HTL Anichstraße

Anichstrasse 26 / 28

Slaughterhouse block

Erzherzog-Eugen-Straße 25 - 38

Racing school & kindergarten

Pembaurstraße 18 & 20

Rapoldi Park

Leipziger Platz

Tivoli

Sillufer / Pradl

Palais Ferrari & Old Garrison Hospital

Weinhartstrasse 2 - 4

Provincial vocational school

Mandelsbergerstrasse 16

South Tyrolean settlement Wilten West

Speckbacherstrasse

Dollfußsiedlung & Fischersiedlung

Weingartnerstrasse

Städtisches Hallenbad

Amraserstraße 3

Pembaurblock

Pembaurstraße 31 – 41

Hungerburgbahn & Nordkettenbahn

Congress Centre / Rennweg 39